Most of Justin Bieber’s vocals on Purpose were recorded in Studio 3 at the Record Plant in LA.

Most of Justin Bieber’s vocals on Purpose were recorded in Studio 3 at the Record Plant in LA.

In a transition overseen by long-term collaborator Josh Gudwin, teenage prodigy Justin Bieber has become a grown-up pop star.

Since breaking through to an international audience in 2009 at the tender age of 15, Justin Bieber has at times demonstrated how not to grow up in public. Bieber’s fourth studio album, released last November, was thus a make-or-break proposition. Three years after his previous studio album, Purpose was to be his first fully fledged adult project, and likely career-defining.

Unsurprisingly, Bieber’s manager, Scooter Braun, and record company took no chances, and explored all possible avenues to make sure the new album would be a success. Writing camps were organised, and Bieber spent time working with household names like Rick Rubin and Kanye West. In the end, however, Bieber reduced his team to the bare essentials: just two guys with whom he felt entirely at ease.

On the writing side, this meant a central role for Jason ‘Poo Bear’ Boyd, while Josh Gudwin held everything together on the studio and production side. This involved logistics, taking care of album A&R, engineering all the overdubs to the writers’ backing tracks, including Bieber’s vocals, mixing most of the songs, and in general being responsible for delivering the album. It earned him an unusual ‘album producer’ credit.

On the writing side, this meant a central role for Jason ‘Poo Bear’ Boyd, while Josh Gudwin held everything together on the studio and production side. This involved logistics, taking care of album A&R, engineering all the overdubs to the writers’ backing tracks, including Bieber’s vocals, mixing most of the songs, and in general being responsible for delivering the album. It earned him an unusual ‘album producer’ credit.

Solid Support

Josh Gudwin has been Bieber’s sidekick for half a decade. The engineer and mixer has enjoyed a fairly meteoric career, studying at Florida’s Full Sail University during 2005-2006, interning at Track Records Studio in LA, working with songwriter Esther Dean, and most of all studying for two years with America’s number one vocal producer, Kuk Harrell. In the process Gudwin clocked up an array of big-name credits, including TI, Lionel Richie, T-Pain, Quincy Jones, Rihanna, Jennifer Lopez, Carly Rae Jepsen, Celine Dion and Pharrell Williams. However, his first meeting with Bieber in 2010 proved the most significant of his career to date, and Gudwin has since worked with Bieber on studio, remix and compilation albums like Under The Mistletoe, Never Say Never: The Remixes, Believe, Believe Acoustic, Journals, and Live At Madison Square Garden.

From his home studio in Los Angeles, Gudwin recalls the earliest beginnings of what was to become Bieber’s first adult album. “The sessions with Rick were Scooter’s idea, and while he and Justin were working I was literally just sitting on Rick’s couch and watching. Kanye and Justin hook up from time to time and develop big creative plans, but they both end up doing their own things, so nothing ever comes of them. We also did not use any material that come out of the writing camps. It was just a matter of seeing what was out there. In the end, Justin didn’t want outside people around who he doesn’t know that well, so I was fortunate to be in a position to really support his vision and help him create a solid body of work.

“Poo Bear also was central in the making of the album, and Scooter always gave opinions and suggestions. We had discussions along the lines of helping Justin to find his feet and direction, but a lot of what we did was just writing and recording new songs, and seeing what came out. There were some songs, mostly written by Poo Bear, that rose to the top, and we realised we had to build around them. It kind of naturally progressed. In the end it took Justin about two years to get clear on where he wanted to go. Poo Bear and I knew what Justin liked, and we brought in many other songwriters, and when Skrillex came in it went one step up again. But Justin was directly involved with the entire process of making the album and he has full accountability on this one.”

Producer, engineer and mixer Josh Gudwin has been Justin Bieber’s right-hand man for many years.

Producer, engineer and mixer Josh Gudwin has been Justin Bieber’s right-hand man for many years.

Purposeful

Gudwin, Poo Bear and Bieber engaged a proliferation of songwriters and producers in the making of Purpose that is impressive even by the sprawling standards of 21st Century pop/R&B albums. In addition to Skrillex there were dozens of others, amongst them Diplo, Ed Sheeran, Benny Blanco, Soundz, Mike Dean, Michael ‘Blood Pop’ Tucker and Ian Kirkpatric. Normally this would be indicative of a scattered and disjointed album, but in fact, Purpose hangs together pretty well, which probably contributed to the album’s remarkable commercial success. After Adele’s 25, Purpose is probably the most successful album of the Winter of 2015-2016, and at the time of writing it had already spawned four major hit singles, including three UK and US number one hits — ‘What Do You Mean?’, ‘Sorry’ and ‘Love Yourself’ — with ‘Where Are Now’ not far behind. At times these songs were battling for the highest chart positions amongst themselves.

“We began work on the album in 2013 and for the last year we worked full-time on it,” says Gudwin. “I kept an overview of the entire project, and managed all the files, and the contacts and exchanges with the writers and producers. We wrote and recorded in various studios, in LA, Atlanta, New York, Toronto and even as far away as Greece, but mostly we recorded at the Record Plant in LA. The SSL 3 room is one of the best sounding rooms in LA. I love the monitoring system. I bring my own main monitors, the ATC SCM25As, which are also my favourite for mixing, as well as my NS10s and little Bose Freestyles.

“Justin loves that studio, and regards it as home away from home. Sessions can take place anywhere, but when you remain in once place it’s easier to maintain consistency and make sure things always sound the same. I did almost all Justin’s vocal recordings at the Record Plant, apart from for a couple of songs, when I was not available. It’s a pretty easy process, because Justin has been doing this for so long that he has a very good knowledge of how to sing in the studio and the techniques that are used. Sometimes we will do a few takes and I will comp that later, sometimes I record him line by line. Basically my job is to capture him in the right way, and then I design his vocals and place them in the track.

“I use various microphones to record him, like the Sony C800G, Telefunken ELAM 251, Neumann U47 or U67. It depends on the sound we want. It’s pretty intuitive. We simply pick a mic, he starts singing and if it isn’t right, we try another one. We like to keep it moving. The mic pre usually is a Neve, and I like to use the Tube-Tech CL1B compressor on the way in, because it’s smooth and gives me the control I’m looking for. After that everything is in the box, apart from some hardware effects I like to use right at the end of the mix, for which I go through a few specific channels on the desk. For the rest my sessions are entirely inside my laptop, so I can travel and set up anywhere. I have an expansion chassis with an HDX card and two UAD cards, and can easily plug in to any studio.”

Speedy Sound

The current direction in R&B/pop sees artists and production teams using a lot of sound design to chisel out a distinctive sonic identity. Gudwin explains how he went about creating a distinct sound world for Bieber’s album, including the singer’s vocals. “Often a major part of the sound design already comes from the producer. Skrillex is really good at creating his own sounds, and I then create vocal sound designs to go with that. But with other tracks I often go in heavy to create additional sounds and effects. Once I get the session from the producers, it’s pretty much just me.

“Every song is different, and therefore every vocal requires different ’verbs and delays. Justin gives me full creative freedom when it comes to his vocal sound, but if he doesn’t agree, he’ll let me know. I edit the vocals as I go, and I groove them, in real time. When Justin walks out of the vocal booth, I like things to sound as good as possible as quickly as possible, also because he wants to hear it back like that almost immediately. I then continue adding sounds and effects, and get into doing a rough mix, dialling in the finer details.

“I learned about the importance of speed from Kuk. When I worked with him he’d have the vocals recorded and edited and loaded into the track, and I would come in and it used to take me two hours to do a rough mix. Kuk said, ‘Just take 30 minutes, bro.’ So I learned to do a rough mix very quickly, and at the end of the day, that often is the sound of the record. The rough mix is often more important than the final mix, because it sets the direction for the song, and if the artist likes that, you don’t want to lose that by redoing sounds and so on. So my final mixes almost always are refinements of the rough.”

Getting The Rough

‘Sorry’, the second single from Purpose, a US and UK number one, is a good example of the way the album came into being and of Gudwin’s mix approach. “Originally Skrillex was going to do his own mixes,” says Gudwin, “with me just doing the vocal mixes, sending him the a cappellas. But he was on tour in India and did not have time to do anything. So he sent me all his sessions in Ableton, and I loaded them into Pro Tools and I started to mix off that. I first did a rough mix, which in this case involved me digging in for 30 minutes to an hour. I’m not paying a lot of attention to the technical aspects at this stage, I’m just putting on plug-ins quickly to get them to do what I want them to do. I do a lot of EQ’ing, but carving out frequencies, and only rarely boosting.

“I’ll start at any place in the track where I feel inspired to start. Basically I’ll go in and start scrubbing, like washing a car. I go all the way down the session, and I’ll dig into the vocal design, and will add EQ and then effects, and I’ll do drops and filters and whatever is needed to create space and movement. Once I can listen to the session without anything bothering me, that is the rough mix. I’ll put it in a folder and I’ll send it to Justin, and he’ll listen to it a thousand times, and sometimes the rough becomes the final mix. If we’re going with the rough, I’ll just do some final detail at the very end. For example, with ‘What Do You Mean?’ we literally went with my rough mix. The beat and song are very straightforward, there is nothing crazy, and the rough had the feel, the vibe, and that was it.”

The mix of ‘Sorry’ was partly done at Henson Studio D, as were various other sessions for the album. This photo from one of the Henson sessions shows the room’s SSL G+ console with, left to right, engineer Peter Mack, Josh Gudwin, producer Maejor Ali and Justin Bieber.

The mix of ‘Sorry’ was partly done at Henson Studio D, as were various other sessions for the album. This photo from one of the Henson sessions shows the room’s SSL G+ console with, left to right, engineer Peter Mack, Josh Gudwin, producer Maejor Ali and Justin Bieber.

By contrast, ‘Sorry’ was a complicated session and the final mix took a lot of time; so much so, in fact, that Gudwin got in some extra help. “I did the final mixes for the album mainly at the Record Plant,” recalls Gudwin,” but also at Henson Studio D, and even did some mixes at Jungle City in New York. The workload got so heavy towards the end that I asked my buddy Andrew Wuepper to help me out for the last two weeks. Even together we were doing 16- to 20-hour days! We’d go to and fro, with him mixing a song for a few hours and then I would go in for a bit, and then he’d mix some more. Doing these mixes together was a treat, because normally our job is so self-obsessed. We started the final stage of the mix for ‘Sorry’ at Henson and worked on it through the night, and then took a 6am flight to New York and went straight to Jungle City and finished the mix that same day/night. Julia Michaels came to the studio to listen and she added some quiet background vocals in the hook. Once I got her parts in, the mix was done. The song was mastered the next day.”

Andrew Wuepper adds: “I have known Josh for many years, so it was natural for him to call me one day, saying he was totally overwhelmed with the Bieber project, and would I come in and help him out on a couple of mixes. He was having all the responsibilities for delivering the album, and wasn’t only mixing, but also still finishing production on some songs, with parts still being recorded and replaced. He had to deliver 17 mixes in two weeks! In the end he and I finished the mixes of seven songs during those two weeks. I also went with him to New York, because we still had to start the mix of the song ‘Children’ — we were waiting for some files from Skrillex — and we needed to finalise the mix of ‘Sorry’. They also wanted Josh to be there for mastering, and on top we had literally gone for several days without sleep by that stage, so he needed a second pair of ears to fall back on.”

Sorry State

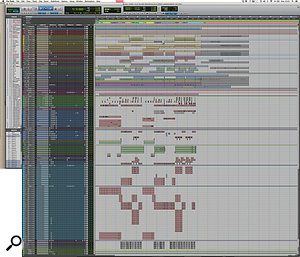

‘Sorry’ is a 100bpm EDM pop track, with Jamaican influences in the rhythm, and featuring a characteristic five-note horn hook. The music and vocal sounds are characteristic of the album: light, open, smooth, airy, breathy. The Pro Tools mix session consists of about 125 tracks: not unusual by today’s standards, but still considerable.

This composite Pro Tools Edit Window screen capture shows the entire mix session for ‘Sorry’.At the top of the session is a master and a mix print, and below that are three group tracks in red for all drums, all bass, and all keyboards, followed by nine drums and percussion tracks, five bass tracks, a mish-mash of 16 tracks that include horn tracks, some aux tracks and outboard effects, more percussion, a piano track and a string track. Clear order is restored again with Bieber’s lead vocal tracks (blue) and associated delay tracks (green), live room and outboard prints, tons of backing vocal tracks (11 by Bieber, 30 by singer Trevon Trapper, all in light blue, and four by co-writer Julia Michaels), and finally, in green, a group of aux effect tracks at the bottom.

This composite Pro Tools Edit Window screen capture shows the entire mix session for ‘Sorry’.At the top of the session is a master and a mix print, and below that are three group tracks in red for all drums, all bass, and all keyboards, followed by nine drums and percussion tracks, five bass tracks, a mish-mash of 16 tracks that include horn tracks, some aux tracks and outboard effects, more percussion, a piano track and a string track. Clear order is restored again with Bieber’s lead vocal tracks (blue) and associated delay tracks (green), live room and outboard prints, tons of backing vocal tracks (11 by Bieber, 30 by singer Trevon Trapper, all in light blue, and four by co-writer Julia Michaels), and finally, in green, a group of aux effect tracks at the bottom.

“This is an actual working mix session, and yes, it is big,” agreed Gudwin. “I’m not so focused on organisation because when you’re on deadline, you don’t always have time to label the session from a visual standpoint. The stem sessions that I create from my mix sessions are super-clean, though. I do usually have the vocal delays as separate tracks, on which I pull the audio I want to treat, and at the bottom of the session I normally have a template of aux effect tracks, in green, with a hall reverb, a plate reverb, and a long reverb; three delays — half-note, quarter-note and eighth-note — and two ping-pong delays and a UAD Roland Dimension D. They are my utility delays and utility reverbs, and they’ll be modified for each session.”

“When I first came in,” recalls Wuepper, “and we were working on the first couple of songs, I showed Josh the template of how I like to work. He isn’t really picky about how the sessions are organised, but I am, so I asked him if I could move certain things. He agreed and so we got used to working in that format. I always have sub buses at the top of my session, in this case ‘All Drums’, ‘All Bass’ and ‘All Keys’, and where appropriate I will also often have ‘All Guitars’, ‘All Lead Vocals’, ‘All Backing Vocals’ and ‘All FX’. Part of the logic behind that is that master faders have a deeper bit resolution than auxiliary tracks, so if you are attaching a master fader to control the input of those aux tracks, in theory you can push a little more gain into those aux tracks.

“I tend to put instruments together that musically sound together, so in this session the horn sample, to which I added a sub-bass, is next to the 808 track, which is the track called ‘bs2-1’ at the bottom of the bass tracks. In my mind, I treated the horn and the 808 as one thing. I am thinking of it in feelings. Whatever group of instruments collectively adds a certain feeling to a song, I’ll treat as one entity, rather than treat every piece as a different thing. We wanted the low end to be big throughout this song, and the verses had the kick drum, and in the B section the 808 comes in, but it didn’t have enough warmth or low end, so we got that from the horns.

“When Josh and I started work on this song it was already pretty close. The production was stellar, Justin’s vocal sounded astounding, and the rough mix was really good. Many people were already in love with it and the record company had picked it as the next single, so we were not going to change the direction. Basically our approach was to get it ready for commercial release, which involved making sure the bass is tight, the vocal pops out, that the general feel is there, and that the ideas that are already there are enhanced as much as possible. Most of my contribution consisted of detailing the reverbs, adding processing so that the bass sounded bigger, and making sure the compression treatments on the vocals and drums were smooth. It really was a matter of bringing the track even more to life with a last sheen of polish.”

Vocal Focus

This trio of plug-ins makes up Josh Gudwin’s default vocal processing chain: the UA SSL E-Channel and LA-2A compressor, and Waves C6 multiband compressor.

This trio of plug-ins makes up Josh Gudwin’s default vocal processing chain: the UA SSL E-Channel and LA-2A compressor, and Waves C6 multiband compressor.

“Most effects and treatments in this session are on Justin’s vocals,” explains Gudwin. “The other tracks didn’t need that much. Skrillex’s and Blood’s drums and percussion tracks sounded pretty good when they came in. I use a lot of UAD SSL E-channel plugins, and I have that on the two kick tracks at the top. I can get a great overall sound using just the compressor and EQ of that plug-in. The first snare also has a FabFilter Pro-Q 2, which is a great EQ, and the second the Xfer Records LFO Tool and the SoundToys Filter Freak, both to get the snare pumping.

“Most effects and treatments in this session are on Justin’s vocals,” explains Gudwin. “The other tracks didn’t need that much. Skrillex’s and Blood’s drums and percussion tracks sounded pretty good when they came in. I use a lot of UAD SSL E-channel plugins, and I have that on the two kick tracks at the top. I can get a great overall sound using just the compressor and EQ of that plug-in. The first snare also has a FabFilter Pro-Q 2, which is a great EQ, and the second the Xfer Records LFO Tool and the SoundToys Filter Freak, both to get the snare pumping.

“There are only three keyboard bass tracks active, and they’re all the same part, which I pulled onto different tracks so I could affect each differently. I prefer that to automating one track. The first bass track has the Brainworx EQ, doing some M-S processing, and the Little Labs Voice Of God, adding some sub. Another track has the Waves Renaissance Compressor, not doing much, and the iZotope Ozone, which is widening and EQ’ing, and the third bass track has the UAD LA2, keeping things in place.”

Wuepper: “Josh asked me if I could make the bass sound bigger and fatter, with some more sub as well. So I inserted UAD’s Voice Of God, which really is a subharmonic synth, and I used an outboard Fairchild 670 to control the sub, to make sure that lowest octave would not blow up your speakers! The 670 was one of the few pieces of outboard that we used, the other one being a Bricasti M7, which supplied reverb to every mix we did for the album. At the beginning of ‘Sorry’ you can hear these big percussion hits with a big reverb tail, which came from a ‘London Plate’ reverb on the Bricasti. I cranked up the reverb as much as possible, going too far with it, and then backed it off a bit. Another piece of outboard that we used on the entire album, particularly on big synth sounds, was the Dolby SR unit. Originally designed for noise reduction on tape, it acts like a high-harmonics generator, a like the Aural Exciter, and we found that it added some breathiness and air that sounded cool.”

Samples & Snippets

Gudwin picks out a few other interesting tracks, beginning with a vocal track named ‘vcls’. “That track contains a vocal sample that Blood made of Justin’s vocal. I’m just touching that with the LFO Tool for a bit of pumping, I take out some high frequencies with the Pro-Q 2, and then use the SoundToys Microshift for a slight pitch-shift/chorusing effect. ‘Sry1V’ below that is the vinyl sound in the track. ‘$JBU’ is the main lead vocal bus, on which I have the UAD 1176, Waves De-Esser, Manley Massive Passive, Metric Halo Channel Strip. The sends are to the generic aux tracks at the bottom of the sesion: verb, ping-pong delay, Dimension D. Below the lead vocal bus is the print track of a Bricasti outboard.”

Wuepper: “There are two tracks called ‘Bric’ around the main vocal bus; the one above is the print from the Bricasti effect that was used on the percussion, and the one below is the print of the Bricasti reverb on the vocal. Next are Josh’s vocal delays. Putting delays on audio snippets [ie. copying short vocal clips to new tracks and applying delays as inserts, rather than automating a send from the main vocal track] is a pretty interesting way of doing things. I’ve not seen anyone else do this, but it makes it easier for Josh to manipulate these delays and to go deeper into the effect. He can really fine tune the delay times and decay lengths and so on. Sometimes the feedback you get with plug-ins can act a little weird, and this approach allows him to have more control.”

Gudwin: “The five green tracks are all vocal throws and delays. I don’t like to automate delay throws via aux tracks. The top green track is the master track for the delays, ‘JB Throw All’, and it has a compressor and an SPL Vitalizer. The ‘1147’ delay track has the UAD Cooper Time Cube, with a quick ping-pong-y flutter delay that I use to widen, and the track called ‘1167’ has a basic eighth-note delay from the Echo Boy. The ‘A’ insert is Auto-Tune, but it’s not working on these tracks. When needed, our vocal tuning is normally done by Chris ‘Tek’ O’Ryan in Melodyne. I sometimes do it myself, if I have the time do it, in the stand-alone version.

“The blue vocal tracks below the vocal delay tracks are the main lead vocal comp tracks, and on many of them I have the UAD SSL Channel Strip, UAD LA-2A, and the Waves C6 multiband compressor, and sometimes also the Pro-Q 2 EQ. The ‘DLYP’ track has a delay pan effect, with the SoundToys Primal Tap delay and Panman auto-panner, SSL Channel Strip and the P&M Vinylizer. ‘White’ and ‘Master’ are printed reverbs recorded in two rooms at Henson. They are my main plug-in vocal reverbs, and the green tracks below are pitched with the Elastic Audio X-Form [in Pro Tools] and effected with the Waves H-Compressor for a pumping effect. I pitched the reverbs up an octave or two, and I mixed them in very low. The ‘PCM’ and ‘PC1’ tracks are prints from ping-pong delays from the Lexicon PCM42 outboard.

Formant shifting in SoundToys’ Little AltarBoy helped create an experimental ‘radio’ effect on some of Justin Bieber’s backing vocals.“Justin’s backing vocal tracks all go to the group track called ‘JBG1’, on which I have a Waves De-esser, an SSL Channel and the C6 multiband compressor, plus there are a number of delays and reverbs via the sends. Trevon’s backing vocals all go to ‘JBTR’, which has similar effects. I wanted to fill the song up a bit more, and sometimes it’s not the most enjoyable process for an artist to sing all these background parts. Plus a different vocalist will add a different texture to the song, as long as it complements the lead vocal and the record. As I mentioned, Julia added her vocals during the final mix in New York, and her group track also has the De-esser, SSl Channel and C6. Right at the bottom are some effects tracks, with the Dimension D and group delay throws, and so on.

Formant shifting in SoundToys’ Little AltarBoy helped create an experimental ‘radio’ effect on some of Justin Bieber’s backing vocals.“Justin’s backing vocal tracks all go to the group track called ‘JBG1’, on which I have a Waves De-esser, an SSL Channel and the C6 multiband compressor, plus there are a number of delays and reverbs via the sends. Trevon’s backing vocals all go to ‘JBTR’, which has similar effects. I wanted to fill the song up a bit more, and sometimes it’s not the most enjoyable process for an artist to sing all these background parts. Plus a different vocalist will add a different texture to the song, as long as it complements the lead vocal and the record. As I mentioned, Julia added her vocals during the final mix in New York, and her group track also has the De-esser, SSl Channel and C6. Right at the bottom are some effects tracks, with the Dimension D and group delay throws, and so on.

“Back at the top of the session, the drums, bass, and keys group tracks each have the Waves L2 on them, but barely touching the compression on that, and they go to the Master track at the top, which has the UAD SSL E-Channel, Manley Massive Passive, Oxford Inflator for a touch of processing, and the FabFilter Pro-L compressor. Tom Coyne mastered the album with Randy Merrill at Sterling Sound. I gave them the option to use the mix without and without my mastering bus treatments, and sometimes they did, and sometimes they didn’t. But especially with the Skrillex songs, they were already hitting in a certain way, and many of the mixes were done through the mastering chain that we already had, which was hard to match.”

‘Love Yourself’

One of the big challenges Josh Gudwin faced on ‘Love Yourself’ was cleaning up Ed Sheeran’s rough-and-ready electric guitar take. Doing so involved a combination of amp simulation (Waves GTR), dynamic EQ (FabFilter Pro-MB) and noise reduction (Waves NS1).

One of the big challenges Josh Gudwin faced on ‘Love Yourself’ was cleaning up Ed Sheeran’s rough-and-ready electric guitar take. Doing so involved a combination of amp simulation (Waves GTR), dynamic EQ (FabFilter Pro-MB) and noise reduction (Waves NS1).

The third number one single from the Purpose album was ‘Love Yourself’, written by Ed Sheeran, Benny Blanco, and Bieber, with Blanco producing. With just one electric guitar, played by Sheeran, a trumpet, a lead vocal and some backing vocals, ‘Love Yourself’ is a rather unlikely worldwide hit. Despite the song’s sparseness, the Pro Tools session for ‘Love Yourself’ contains more than 40 tracks, thanks to Gudwin’s sonic treatments. On top of his 10 standard aux effect tracks, he also split the vocal over numerous different tracks to be able to treat each vocal section differently, and added some rhythmic and atmospheric Jon Hassell-like effects to the trumpet.

The third number one single from the Purpose album was ‘Love Yourself’, written by Ed Sheeran, Benny Blanco, and Bieber, with Blanco producing. With just one electric guitar, played by Sheeran, a trumpet, a lead vocal and some backing vocals, ‘Love Yourself’ is a rather unlikely worldwide hit. Despite the song’s sparseness, the Pro Tools session for ‘Love Yourself’ contains more than 40 tracks, thanks to Gudwin’s sonic treatments. On top of his 10 standard aux effect tracks, he also split the vocal over numerous different tracks to be able to treat each vocal section differently, and added some rhythmic and atmospheric Jon Hassell-like effects to the trumpet.

“It’s a super-simple song,” explains Gudwin. “The guitar was played by Ed, and I overdubbed my buddy Phil Beaudreau playing trumpet. The first time we heard the song it was just electric guitar and vocal, and everybody fell in love with that. Benny tried to add a couple of instruments, but everybody preferred the basic version. Sometimes you have to make the decision to add nothing else, so that’s what we went with. That was easy. Scooter predicted it would be a number one, but even though I love the song, I wasn’t so sure!

“Ed’s original guitar was quite noisy and buzzy. It sounded like he was on the road and had just plugged in quickly to get an idea down. So I selfishly wanted a cleaner guitar sound and had a couple of guys coming in to replay the guitar part, but it never sounded anywhere near as good. It just kept sounding too different and without the right feel. So I decided to go with Ed’s guitar and treated it with the Waves NS1 noise suppressor, the Waves GTR plug-in, and filtered it with the FabFilter Pro-MB, and an Avid EQ, taking out around 3kHz.

“I didn’t want to add much to the session, but I did continue working on it until it felt right to me. I wanted to maintain the fact that the arrangement is very bare, yet also add small things to make it sound fuller than it is. These small additions are like ear treats. When Phil came in to play his trumpet, I recorded him sitting in a chair, with a Royer mic right underneath and just a Neve pre, and no compression. Right after cutting it, I immediately worked on the sound. I put a reverse reverb on it, and a UAD MXR flanger and a delay. The ‘Audio 1’ track has a trumpet loop that I made, a texture thing on which I had the UAD SPL Vitalizer

“Below the trumpet section are Ed’s vocals, on which I have the [Avid] BF76 compressor and a channel strip, and at the top is his vocal bus, on which I have the FabFilter Pro-2 EQ. I also had the Bricasti on Ed’s voice, as well as a UAD LA2. Next are Justin’s vocals, with I overdubbed in New York. Almost all the regular vocal tracks have the UAD SSL Channel, LA2 and the Waves C6 multiband compressor. These three plug-ins work great on his vocals, so I tend to stick with them. Each of the vocal tracks has slightly different settings from them. They all go to Justin’s lead vocal bus above them, which has the FabFilter Pro-DS de-esser and the Pro-2 EQ. Justin’s lead vocals also go through the Bricasti, and the effect is printed. My own four backing vocals went through a vocal bus on which I had the SSL Channel, and a compressor, but they didn’t do much, nor did the sends. These vocals are very much in the background, I just wanted to add some texture really quickly. Finally, at the top of the session everything went through a Master track, on which I had the UAD SSL channel, mainly for compression set to mid-attack and auto-release — without drums you don’t need the slow attack and quick release — a Massey EQ, boosting 100Hz and 16kHz, a FabFilter Pro-L for level, and the Sonnox Oxford Inflator to add some sheen.”

‘What Do You Mean?’

Written by Justin Bieber, Jason ‘Poo Bear’ Boyd, and Mason ‘MdL’ Levy, and produced by Bieber and MdL, ‘What Do You Mean?’ is another light-footed EDM pop track with Jamaican ‘tropical house’ influences — and another global chart-topper. The song’s Pro Tools session is simpler than that of ‘Sorry’: of its 67 tracks, 20 are Levy’s music and beats, 30 are lead and backing vocal tracks, seven are unused Gudwin effect tracks, and 10 are the standard aux effect tracks Josh Gudwin loads into all his projects. Pro Tools clip names reveal the sources of all Levy’s sounds, which include Shocking Expansion 2, VES2 samples, Samplephonics, Kontakt 5 and EDM Spire, with the song’s characteristic flute sample apparently coming from Spectrasonics’ Omnisphere and ReFX’s Nexus. The 25 lead vocal tracks are to a large degree Gudwin’s creation: he split the lead vocal up over several tracks, and created several tracks of vocal effects from the lead vocal.

“Mason works in Logic, and his stems are pretty good. I did a few edits to them, but other than that didn’t treat them very much. I EQ’ed the clock sound with the UAD SSL Channel to cut some mid-range to make space for Justin’s vocals, and added some reverb from a Dimension D. I also boosted mid-range on the loop to make it cut through, and I had a UAD Neve 1081 on the kick. I love the UAD stuff. It rocks! The bass had the UAD LA2 compressor to even it out a bit, and the piano has a Waves C6, boosting low mids and compressing the highs, and some more Dimension D. The main synth has the SSL Channel again, boosting high mids and low mids to create a bigger cushion, and the flute sample has the UAD ‘blue stripe’ 1176 compressor, hitting it pretty hard.

“There were a few more complicated vocal effects, like the ‘JG FX’ track, on which I used the Vitalizer doing some spatial expanding, a UAD Fatso to thicken it up, and I then cut some low mids with an EQ, and used a de-esser. This effect track gave more depth to the vocal and made him sound more like an angel! Underneath that are two ‘Radio’ tracks [which sound like they could have come straight from Peter Gabriel’s ’80s Fairlight experiments]. I used Auto-Tune to pitch the vocals up, and then put on a SoundToys AlterBoy, which changed the formant, and then I’m filtering 350Hz and below.

“Below the ‘radio’ tracks are all my vocal delay tracks, in green as usual, with the bus for all delay throws at the top. One delay track, ‘Splaater’, is a flutter delay with Auto-Tune and the Cooper Time Cube, and the other two have the Waves H-Delay and SoundToys Echo Boy. They’re both quarter-note delays, but with different feels. Below the delay tracks are some ad lib tracks, and all the actual lead vocals, pulled out over several tracks. Most of them have my regular trio of UAD SSL Channel, LA2 and Waves C6 plug-ins, and all vocals are sent to the ‘JB Buss’, on which I have the FabFilter DS de-esser, a Manley EQ doing light cuts at 330Hz, 560Hz and 3kHz, and then a whole bunch of sends to my regular aux tracks at the bottom: a hall reverb, a plate reverb, a light quarter-inch delay, a light ping-pong delay and a Dimension D.

“Further down are four Justin backing vocal tracks, which go to a bus above them, ‘JBG1’, on which I have the SSL Channel, boosting highs and cutting lows and doing some heavy compression, a UAD 33609 compressor, and then the Waves Enigma [phaser/flanger] on a Mutron setting, adding some sweeping sounds. The sends are once again hall and plate reverbs, a quarter-note and a ping-pong delay and a UAD Roland Dimension D. Once Justin had decided to go with my rough mix, I spent another half hour on it, doing some EQ adjustments, and that was it.”

Andrew Wuepper

“I have always known that I wanted to be a professional mixer,” says Andrew Wuepper, and he proved unusually tenacious and inventive in achieving his goal. Wuepper attended the Conservatory of Recording Arts in Arizona before moving to LA in 2006 with the aim of working at Larrabee Studios — where, at the time, three of the world’s leading mixers, Dave Pensado, Manny Marroquin, and Jaycen Joshua, were carving up most of the international pop charts between them.

Mix engineer Andrew Wuepper was brought in by Josh Gudwin towards the end of the album production in order to meet punishing schedules.

Mix engineer Andrew Wuepper was brought in by Josh Gudwin towards the end of the album production in order to meet punishing schedules.

“I was, and still am, fascinated by how you can change the way a record is heard and felt by manipulating the sounds in them,” explained Wuepper. “That whole world was like a rabbit hole for me: I needed to find out how to do that. I wanted to work with the biggest mixers, and they were at Larrabee, so I sent my resume about 50 times to the studio. They turned me down every single time! Finally, at the 51st time, they called me for an interview about an internship. I got the job, and worked for about six months cleaning floors and the toilets, and doing anything I could to get noticed. One of the biggest things I did as an intern was to finally work out how to get the floor in one of the hallways clean. It was a concrete floor with shiny paint to make it look like marble, and it always looked dirty. I looked up what concoction of chemicals would do the job, and I managed! It was a mixture of Pine Sol and Windex. That got me on the radar.

“After about six months, Dave Pensado needed a new assistant, and there were five people in line before me to get that position — the studio had six runners at the time. I didn’t think I had a chance to get that job. But Dave is very particular about whom he works with, and the five people in front of me did not work out in the first week. So he gave me a try, and two days later I was his new full-time assistant! It meant that I basically jumped into a hyper mixing boot camp. It was straight into the frying pan. From my third week in I worked 15-18-hour days, seven days a week, for nine months straight, without a single day off!

“This was in 2007. Dave was mixing with Jaycen Joshua at the time, and they were using two rooms, so I was the assistant mix engineer for two rooms. It crystallised a lot of things into my brain of how to do things. Not just mixing, but also more general things like how to keep files organised, how to deal with clients on the phone, how to manage a really heavy workload, and so on. Having that down is half the battle to becoming a successful engineer and mixer, because it is a business too. When you have those things kind of on autopilot and you don’t have to worry about them it leaves more space in your brain to be creative. Technically I was doing everything for Dave, from setting up his sessions to lining up the tape machines to laying things out over the desk, so that all he had to do was come in and push up the faders and turn the knobs.”

After two years with Pensado, Wuepper went on to work as producer Tricky Stewart’s engineer, gradually becoming his full-time mixer as well, and clocking up all manner of big-name credits, including Beyoncé, Usher, Katy Perry, Michael Jackson and even one Justin Bieber. Wuepper went freelance in 2011, and set up his own studio, featuring an SSL desk and a wide selection of outboard gear. At the time of writing he had closed this studio, and was busy creating a new facility in his own house. He plans to retain most of his outboard, but not his SSL.

“I’m so comfortable mixing in the box now, and have a Chandler summing mixer for a little bit of that sweetness that sending the signal through electronics adds. But the plug-ins are so good today, there’s no benefit from working on a large console any more, other than that it’s fun. Recalls are a disaster, and it would have been impossible to do the Justin project on a desk. Producers like Skrillex and Diplo and Blood have like seven or eight synths all compressed together feeding side-chains to something else and so on. With today’s modern production techniques, spreading things out over a console slows you down dramatically. Also, I am bouncing around studios all the time and need to be able to instantly recall mixes I did in one studio in another studio. And finally, I am mixing five or six projects at the same time now, so I’m pulling up five or six songs every day, working on this for a couple of hours, working on something else for a couple of hours, and so on. Of course you can only do that in the box.”