We evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of different on-stage playback machines, and offer advice on how to avoid those embarrassing live backing-track pitfalls!

Back in the '70s, playing live and playing in the studio were two completely separate disciplines, and bands were expected to perform on stage without the help of backing tapes. Since then, however, the two approaches have more or less converged and, for many live acts, pre-recorded audio has become an essential part of the show. Nowadays there are a large number of machines available for on-stage playback, from humble drum machines and Minidisc players through to multitrack hard disk systems. As a gigging drummer, I've played along with most of these machines at one time or another, so here's how I rate them for ease of use and reliability in a live situation.

Live Sequencing Hardware

Many of us first learned to program sequences on a drum machine, and these handy little devices are reassuringly simple in concept and reliable on stage. For peace of mind, it's nice if you can find a model (such as the Boss DR660) which displays the name of the song along with its tempo. Modern machines have a good selection of drum and percussion sounds, and if you want to add your own samples, it's possible to use the drum box's MIDI output to trigger a sampler. The first drum machine to feature user sampling was the Emu SP1200, still favoured by US R&B producers for its crunchy (though slightly noisy) 12-bit mono sound. But not all vintage machines are this good — the original Linndrum had a meagre menu of largely crap sounds and couldn't store song tempos, so can safely be consigned to history as far as live use is concerned! Although drum machines are great for programming percussion patterns, song editing is often slow and tedious, and you can quickly run into sequence memory problems.

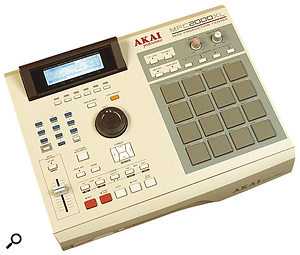

There's a lot of choice when it comes to hardware capable of playing back MIDI sequences on stage, including units that incorporate sound modules (for example, the Roland MC80) or phrase samplers like the Akai MPC2000XL.Photo: Mark EwingHardware sequencers such as the Roland MC500 and MC80 are also reliable and very portable, with good editing facilities and fast location of sections within a song (the latter being very useful in rehearsal). The MC80 has an optional voice expansion board, but most professional users will want to hook up an external sound module or two. This is where the trouble starts; unless the number of external units is kept to a minimum, you can expect long set-up times and complicated, elaborate mixing procedures, plus a certain amount of operator error. Large MIDI set-ups occasionally suffer from timing issues and stuck notes, and there's always a risk of modules not responding properly. It gets worse: loading sequencer floppy disks can be slow, and the number of songs held in sequencer memory tends to be limited. If samplers are being triggered, factor in even more time for programming and disk loading. Programmers need a large brain and a good sense of humour to cope with all this!

There's a lot of choice when it comes to hardware capable of playing back MIDI sequences on stage, including units that incorporate sound modules (for example, the Roland MC80) or phrase samplers like the Akai MPC2000XL.Photo: Mark EwingHardware sequencers such as the Roland MC500 and MC80 are also reliable and very portable, with good editing facilities and fast location of sections within a song (the latter being very useful in rehearsal). The MC80 has an optional voice expansion board, but most professional users will want to hook up an external sound module or two. This is where the trouble starts; unless the number of external units is kept to a minimum, you can expect long set-up times and complicated, elaborate mixing procedures, plus a certain amount of operator error. Large MIDI set-ups occasionally suffer from timing issues and stuck notes, and there's always a risk of modules not responding properly. It gets worse: loading sequencer floppy disks can be slow, and the number of songs held in sequencer memory tends to be limited. If samplers are being triggered, factor in even more time for programming and disk loading. Programmers need a large brain and a good sense of humour to cope with all this!

A modern sampling workstation like the Akai MPC2000XL combines the best aspects of a drum machine and a hardware sequencer, offering good editing and locating facilities along with onboard sampling. Although designed with drum sounds in mind, these workstations are just as happy triggering stereo backing vocal samples, the only limitation being the amount of RAM you have installed — in the case of the MPC2000XL you're limited to 32MB. The MPC machines are sturdy and reliable, and offer quick access to all songs during the show, with programmable mixes, multiple outputs and onboard effects.

Photo: Mark EwingThere are some drawbacks to using an MPC2000XL, however. If you didn't create your tracks on this machine originally, you'll have to make a whole set of one-shot samples to fit into its memory, which is labour-intensive. Selecting the next song before the previous song has come to a complete halt can cause the next song to start immediately (I got burned on that one a few times). If the power goes off, you'll have to reload everything from scratch, which can take quite a while — Akai do offer a Flash ROM option which retains samples in memory on power-down, but it only has an 8MB capacity.

Photo: Mark EwingThere are some drawbacks to using an MPC2000XL, however. If you didn't create your tracks on this machine originally, you'll have to make a whole set of one-shot samples to fit into its memory, which is labour-intensive. Selecting the next song before the previous song has come to a complete halt can cause the next song to start immediately (I got burned on that one a few times). If the power goes off, you'll have to reload everything from scratch, which can take quite a while — Akai do offer a Flash ROM option which retains samples in memory on power-down, but it only has an 8MB capacity.

But, I hear you cry, why not use a computer on stage? Offering good integration of audio and MIDI on a convenient and familiar system, computer sequencer programs would seem to be the obvious solution for live playback. There is, however, one big problem: computers crash without warning, and it appears no-one can do anything to prevent it. Please don't write in saying 'my computer has never crashed' — take it on stage in front of a thousand people, and it will (see the 'Murphy's Law' box for details)!

Magnets & Bad Vibes

A warning about the placement of your on-stage playback machines: you often see drummers playing live shows with huge 'drum fill' monitors set up right next to them. These beasts contain large speakers with massive magnets at the back of them, which can create absolute havoc with magnetic recording media such as cassettes, floppy disks, and hard drives. They may cause backing track machines to behave erratically, or in the worst case might even erase your media!

Another pitfall is vibration, caused by drum kits being pounded, bass PA frequencies, and people dancing or banging their feet on stage. Such 'bad vibrations' can upset the balance of spinning discs, so keep CD players well away from the epicentre. A well-made flight case with thick foam insulation will reduce vibration.

Gear For Two-channel Playback

A variety of machines can handle simple 'mono mix plus click track' playback, the simplest (and oldest) being the stereo tape recorder. A friend recently did a gig accompanied by playback from an old Revox machine (circa 1970) and a two-year-old Mac G4; the Mac crashed, while the Revox sailed serenely on. Tape recorders are a tried and tested technology with an increasingly hip retro look; the downside is that you have to contend with all those nasty tape issues — background hiss, tape damage, stretching, and loss of treble response due to oxide shedding.

Photo: Mark Ewing

Photo: Mark Ewing Although small Walkman-style Minidisc players are extremely portable, it's worth spending the extra money on a more reliable professional model (above) for live performance use. Photo: Mark EwingMinidisc recorders are a cheap and fairly pain-free digital medium. The professional machines are very reliable; you can name each song, and enjoy fast access to any track on the Minidisc. Audio quality is good, but due to data compression not quite as pristine as DAT or CD. DAT recorders appear to be going the way of the pterodactyl, but offer superb quality as well as reliability and resistance to vibration. If you have a couple of grand to spare, you could consider using a three-track DAT recorder for stereo playback plus a click track. DAT tapes are a bit slow to rewind, but you can get two hours of audio on a single tape.

Although small Walkman-style Minidisc players are extremely portable, it's worth spending the extra money on a more reliable professional model (above) for live performance use. Photo: Mark EwingMinidisc recorders are a cheap and fairly pain-free digital medium. The professional machines are very reliable; you can name each song, and enjoy fast access to any track on the Minidisc. Audio quality is good, but due to data compression not quite as pristine as DAT or CD. DAT recorders appear to be going the way of the pterodactyl, but offer superb quality as well as reliability and resistance to vibration. If you have a couple of grand to spare, you could consider using a three-track DAT recorder for stereo playback plus a click track. DAT tapes are a bit slow to rewind, but you can get two hours of audio on a single tape.

The obvious contender for simple two-track playback is the CD player: the sound quality is to all intents and purposes perfect, the player offers near-instant access to any track, and it's quick and easy to burn audio CDs with a computer. However, there are some potential problems: CDs are prone to skip and jump if affected by vibrations from drums, bass or dancers (see 'Magnets & Bad Vibes' below), and CD-Rs made on a computer will not play on all CD players. Whether you choose Minidisc, DAT or CD, portable Walkman-type machines are not recommended for stage use — for the sake of reliability, be prepared to spend a bit more and get yourself a professional rackmount model.

It's doubtful whether anyone uses cassette multitrackers any more, but they're worthy of a mention for historical reasons. The original machines recorded on four tracks and played back in stereo, and on some models the stereo mix could be sent to the front of house independent of the click track. However, these machines are very slow and unreliable in locating the start of songs, and particularly bad if you want to access songs at different ends of the tape in quick succession. Their tape noise resembled a fire in a pet shop, and bad crosstalk occurred on the outputs due to cheap construction. The worst problem, affecting both cassette multitrackers and stereo cassette players, is that different models tend to play at slightly different speeds, resulting in timing and tuning discrepancies. Happily, we now have digital multitrackers (such as the Korg PXR4, Fostex MR8 and Tascam 788) which don't suffer from these problems, though I've yet to see a band use one live.

Murphy's Law

It's been my unfortunate experience that Murphy's Law ('whatever can go wrong will go wrong') is an immutable fact of nature. You can also be sure that the most important live show in your tour — in LA, New York, London, or wherever the most industry bigwigs have come to see you perform, in front of thousands of people and with millions of TV viewers watching live via satellite across 50 countries — is the one where your backing machine will have a heart attack. Remember Roger Waters doing that miserable little tap-dance in deafening silence, when his playback system broke down on the Berlin mega-simulcast of 'The Wall'? Don't laugh, that could be you.

To illustrate my point, the biggest gig I ever did was in the Olympic Stadium in Rome in front of 92,000 people, playing a 3.5-hour marathon concert broadcast live on Italian TV. We were playing along to an ADAT which had its own operator — he located the start of every piece, then, on a cue from our musical director, pressed Play and off we went. The system worked fine all through the set, but Signor Murphy was in the crowd that night, and after we finished the penultimate song the operator forgot to press Stop. The tape kept rolling, and I heard the first click of the count-in of the next song in my in-ear monitors, then silence. I knew then trouble was brewing, and hoped desperately our man had noticed and would correct his mistake by rewinding the tape back to the correct locate point.

Sadly, this didn't happen. Instead of the classic 'click... click... click, click, click, click' count-in, what we got was, 'click... click, click, click, click'. After that, it was every man for himself. I managed to come in on time, but the rest of the band missed the downbeat and came sliding in all over the place. (The fact that the song in question hurtled along at 166bpm didn't help.) Then, to make matters much worse, the ADAT operator suddenly realised his error, panicked and pressed Stop. But by that time, of course, we had already played a few bars (albeit shambolically), and the audience had jumped to their feet and were getting excited. On seeing this, the operator thought everything must be OK, so pressed Play again, effectively putting us miles out of sync with the backing tape, so badly that no one knew where the hell we were. In the end we managed to get him to stop the tape, but for a few agonising minutes we were truly up s**t creek without a paddle.

The bottom line is that faulty machines can be repaired, but there's not much you can do about operator error, apart from delivering a good kick up the mains socket. The moral of the story is that, if you live by the backing tape, you'll die by the backing tape!

Multitrack Playback

Using a multitrack player enables disparate sounds such as percussion, sequenced bass and stereo backing vocals to be recorded on separate tracks, giving more luxurious mixing options. In the '80s, many bands relied on analogue Fostex eight-track tape recorders for stage playback — these robust machines had great sound quality and a very effective, transparent noise reduction system, but their flimsy quarter-inch tapes always seemed a bit of a liability in a boozy live environment. The arrival of digital eight-track tape recorders signalled the end of the analogue tape era, and for many bands the low-cost ADAT machine became the on-stage player of choice. ADATs look chunky and, even if they occasionally chew tapes, they reproduce your backing audio faithfully with no added noise or pitch deviation.

Photo: Mark EwingThe ADAT's chief rivals are the Tascam D-series digital eight-track tape recorders. These too have been known to mangle tapes, but they are on the whole reliable, and their tapes hold nearly two hours of audio. The two digital eight-tracks have subtly different sound qualities: according to a producer friend, the Tascam has a more transparent high end and a wider stereo image than the original black ADAT machines, but the ADAT's bottom end sounds stronger and more solid. Nit-picking sonic comparisons aside, both machines produce super-clean audio and can send seven tracks independently to the front of house, with track eight reserved for the click.

Photo: Mark EwingThe ADAT's chief rivals are the Tascam D-series digital eight-track tape recorders. These too have been known to mangle tapes, but they are on the whole reliable, and their tapes hold nearly two hours of audio. The two digital eight-tracks have subtly different sound qualities: according to a producer friend, the Tascam has a more transparent high end and a wider stereo image than the original black ADAT machines, but the ADAT's bottom end sounds stronger and more solid. Nit-picking sonic comparisons aside, both machines produce super-clean audio and can send seven tracks independently to the front of house, with track eight reserved for the click.

Although you can use 24-track machines such as the Mackie HDR24/96 (top) and Tascam MX2424 (bottom) on stage, you'll almost certainly have to hire a mix engineer to sort out all these tracks at the show.Photo: Mark Ewing

Although you can use 24-track machines such as the Mackie HDR24/96 (top) and Tascam MX2424 (bottom) on stage, you'll almost certainly have to hire a mix engineer to sort out all these tracks at the show.Photo: Mark Ewing

ADATS and Tascam DA88's rewind their tapes fairly quickly, but it still takes a while to get from one end of the tape to the other. To avoid embarrassing on-stage delays while the machine locates the next song, you will probably need to work out your set list first and record the songs in that order on the tape. For live use, it's best to leave the first and last five minutes of a DA88 tape blank, as the recorder's fast-wind mechanism automatically drops to a lower speed when the tape nears its beginning or end.

These machines' locate points are limited: though the ADAT XT machine has ten, other ADAT models offer four, while the Tascam machines have only two. Both manufacturers sell large remotes which offer multiple programmable locate points, but these units are expensive. As mentioned, there is a slight risk of tape damage, which can in the worst case result in aborted playback. If you're serious about using an ADAT or DA88 (whether live or in the studio), my advice would be to buy two identical machines so you can create digital clones of all your recordings.

Even More Tracks!

If eight playback tracks aren't enough for your grand live project, manufacturers such as Mackie and Tascam make professional 24-channel hard disk recorders (HDR24/96 and MX2424, respectively) in sturdy metal rackmount cases. Although their audio can be edited via an external computer, both machines are designed to be used with an external mixer. Wiring up all twenty-four channels would be quite a task, on a par with constructing a recording studio every time you want to play a gig! If your music requires this amount of playback channels, you'll almost certainly need to employ your own sound engineer to make sense of it in a live situation.

You can of course run 24 or more channels of audio plus MIDI from a computer, using programs like Digidesign's Pro Tools or Emagic's Logic Audio. Big American touring bands generally run their shows from a Mac G4, with a second machine ready to take over if the first one crashes. (Apparently Mariah Carey's 'live' act uses a 96-channel Pro Tools system.) If you're tempted to try this, I would advise two things: make sure that the system's hard disk is not cluttered up with rubbish, and take serious steps to protect the computer's mains supply from spikes and surges.

Many 16-track multitrackers (such as the Korg D1600 and Fostex VF16 shown here) are well suited to live use, because they not only provide the flexibility of multitrack backing, but also offer powerful onboard mixing facilities. One major limitation with such systems, however, is that they often have only a few physical outputs.Photo: Mark EwingUsing multitrack playback live opens up a lot of creative possibilities, but multiple channels require careful mixing. A digital mixer with recallable mixes (like the Yamaha O1V) is one way to go, but the whole exercise starts to become expensive and a bit complicated to set up.

Many 16-track multitrackers (such as the Korg D1600 and Fostex VF16 shown here) are well suited to live use, because they not only provide the flexibility of multitrack backing, but also offer powerful onboard mixing facilities. One major limitation with such systems, however, is that they often have only a few physical outputs.Photo: Mark EwingUsing multitrack playback live opens up a lot of creative possibilities, but multiple channels require careful mixing. A digital mixer with recallable mixes (like the Yamaha O1V) is one way to go, but the whole exercise starts to become expensive and a bit complicated to set up.

A cheaper, neater solution is to use a hard disk multitrack recorder with built-in mixing facilities, like the Korg D1600, Fostex VF160, Roland VS1880 or Yamaha AW2816. The advantages are numerous: lots of great mixing options for front of house and on stage, fast access to the songs in any order (good if you tend to change your set list often), flexible routing, and automated mixing. Material can easily be added by overdubbing — for example, you can add vocal cues ("bridge one... chorus one... guitar solo..." and so on) on a spare track all through a song arrangement, and mix these cues into your click track. But it's not all plain sailing — learning how to program such beasts can be hard work if you've not used one before, so allow plenty of time for preparation before the first gig. Also, be aware that, although many of the new digital multitrackers can handle 16 or more playback tracks, these machines may have fewer outputs than you require.

In choosing the specific machine you're going to use, you need to look carefully at its reliability and ease of use. My first experience of on-stage hard disk playback was with the Fostex VF16 multitracker — I did several tours with this machine, and it proved very reliable. However, it has (in my humble opinion) a dog of an operating system, and a manual that is hard to understand. More recently, I've been using the Yamaha AW2816 on gigs. This has the advantage of moving faders (much better than the static kind in demonstrating changes in the mix), and a far more friendly operating system.

No matter what recording format you use, there's always the possibility that the recording medium will experience a sudden failure — ADAT machines in particular are notorious for chewing up tapes without warning. So it's imperative that you make backups of all your carefully crafted backing-track masters.Photo: Mark EwingOne downside I found with the Yamaha AW2816, however, was that, due to all the internal updates it needed to perform, it was extremely slow changing from song to song. The only way to cope with this was to record the whole show as one huge chunk of audio, putting markers at intervals within it to show the start of each individual song. This becomes a bit of a headache with a two-hour, 20-song set, because, when it comes to backing up, the only way to do it is to save the whole recording as one massive file!

No matter what recording format you use, there's always the possibility that the recording medium will experience a sudden failure — ADAT machines in particular are notorious for chewing up tapes without warning. So it's imperative that you make backups of all your carefully crafted backing-track masters.Photo: Mark EwingOne downside I found with the Yamaha AW2816, however, was that, due to all the internal updates it needed to perform, it was extremely slow changing from song to song. The only way to cope with this was to record the whole show as one huge chunk of audio, putting markers at intervals within it to show the start of each individual song. This becomes a bit of a headache with a two-hour, 20-song set, because, when it comes to backing up, the only way to do it is to save the whole recording as one massive file!

Back Up Your Backing!

Whichever machine you choose to perform your backing-track playback tasks, make sure you've got some backup. It goes without saying that you should always have a second copy of your master playback recording medium, be it a floppy disk, DAT tape, CD, ADAT/Tascam tape, external hard drive, or whatever. You could also consider carrying a spare playback machine for emergencies: in my current band we use four of the Yamaha AW2816's multiple outputs for playback, but we also have a pre-mixed mono version of the same tracks saved on Minidisc. The Minidisc is soundchecked every night and ready to play in the event of the AW2816 throwing a wobbler. Of course, if this happens in mid-song there's not much you can do, but at least you can switch to the backup machine at the end of the song.