Beyoncé's second solo album, B'Day, has yielded two of the biggest singles of the year. Jason Goldstein tells us how he put together hit mixes for 'Déjà Vu' and 'Irreplaceable'.

Jason Goldstein is one of the rising stars of the American R&B/hip-hop mix scene. Since the beginning of his recording and mixing career in the early '90s, the 36-year old has worked with Jennifer Lopez, LL Cool J, Rihanna, Mary J Blige, the Roots, Jay-Z, B Rich, Toni Braxton and, most famously, Beyoncé Knowles.

"B'Day is my biggest record to date," he says proudly, and big it is. Beyoncé's second solo album has racked up 3.5 million sales worldwide, and was nominated for a Best Contemporary R&B Album Grammy award. Goldstein mixed 10 of the album's 11 songs, including the worldwide smash hits 'Déjà Vu' (Grammy nominations for Best R&B Song and Best Rap/Sung Collaboration), 'Ring The Alarm' (Grammy nomination for Best Female R&B Vocal Performance), and 'Irreplaceable', which spent 10 weeks at the top of the US Billboard charts.

A Washington DC native, Goldstein moved to Los Angeles in the early '90s. The then teenager responded to a job advert from the legendary Ocean Way, where he honed his recording skills "old school and hands-on". Back in New York, he hooked up with R&B/hip-hop production duo the Track Masters, who gave him his break into mixing. Today Goldstein works mainly from Sony Music Studios in New York.

Jason Goldstein's mix for 'Déjà Vu' used both hardware and software processors. Of the latter, the URS Fulltec EQ (top) added weight to the kick drum, while Sony's Oxford Transient Modulator was used to shape the attack of the kick drum and finger-snap sound.B'Day was the last record, says Goldstein, that he did "as a hybrid of in and out of the box. Everything after that has been 100 percent in the box." Goldstein calls himself a "fairly minimalist mixer", whose immediate instinct is to respect the sounds used by the producer, and not to reach for 'trickery' as a first resort. He prefers not to go overboard with outboard, and the rack of specialist gear that he has assembled over the years is relatively modest. By the time the B'Day songs arrived on his desk, his rack included a Pendulum Audio 6386 compressor/limiter, Avalon 2055 EQ, TC Electronic M3000 multi-effects, 1210 delay and Finalizer mastering processor, two Empirical Labs Distressor compressors, an Alan Smart C2 compressor, an SPL Transient Designer and a Manley Massive Passive EQ. His main monitors are JBL LSR6328Ps.

Jason Goldstein's mix for 'Déjà Vu' used both hardware and software processors. Of the latter, the URS Fulltec EQ (top) added weight to the kick drum, while Sony's Oxford Transient Modulator was used to shape the attack of the kick drum and finger-snap sound.B'Day was the last record, says Goldstein, that he did "as a hybrid of in and out of the box. Everything after that has been 100 percent in the box." Goldstein calls himself a "fairly minimalist mixer", whose immediate instinct is to respect the sounds used by the producer, and not to reach for 'trickery' as a first resort. He prefers not to go overboard with outboard, and the rack of specialist gear that he has assembled over the years is relatively modest. By the time the B'Day songs arrived on his desk, his rack included a Pendulum Audio 6386 compressor/limiter, Avalon 2055 EQ, TC Electronic M3000 multi-effects, 1210 delay and Finalizer mastering processor, two Empirical Labs Distressor compressors, an Alan Smart C2 compressor, an SPL Transient Designer and a Manley Massive Passive EQ. His main monitors are JBL LSR6328Ps.

"I think you should work with what you are given, and make that the best it can sound," explains Goldstein. "When I receive a mix, I look at the [Pro Tools] Edit window first, and see how well the song is recorded, arranged and labelled. With the proliferation of home recording, this is where I start. Is it laid out on a tempo grid? If not, I may have to put things into Beat Detective and create my own tempo map, in case I have to do edits later. If everything is not exactly what it says, I listen to every track individually and label it myself. As you can see on the screen shots, I arrange things in the Mix window the same way as I would on a console, with the drums to the left, then the bass, other rhythmic elements, and then anything that plays for the majority for the record. Out of habit I always put the vocals on 23 and 24 on the console, and the background vocals start to the right of the centre section. Any instruments that play only occasionally go all the way to the right.

"When everything is where and how I want it, I push all the faders to zero, and let the song play and listen to what it feels like. After this I call up the drums and get those to sound really good by themselves. Other things come in gradually, but I get the vocals in quite early on, because I used to have this habit of mixing incredible-sounding instrumentals, and when I brought the vocals up, it was difficult to fit them into the mix. You have to make room for things. So it's all about finding space, using levels and EQ. I don't do a lot of soloing, unless I'm hearing a nagging frequency that's bothering me and I want to find out what it is. So instead everything is up and I will try to EQ things within the context of the whole mix. I can usually get a record to sound pretty good in the first few hours, and then I start to have fun with it. With Pro Tools you have the luxury of printing mixes every hour, so if you move too far in one direction, you can always get back to an earlier mix and build on that."

'Déjà Vu'

Writers: Beyoncé Knowles, Rodney Jerkins, Delisha Thomas, Makeba, Keli Nicole Price, Shawn Carter

Producers: Beyoncé Knowles, Rodney Jerkins

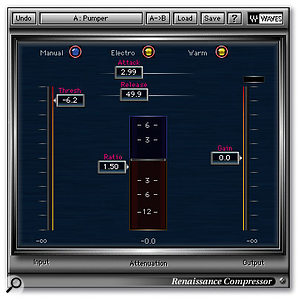

Bass processing included another URS Fulltec EQ (top), while Sony's Oxford Dynamics was used to compress the live bass and Waves' Renaissance Compressor (bottom) was used to duck it every time the kick drum hit."Basically, this song is a take on what Quincy Jones did with pre-Thriller Michael Jackson. Beyoncé really wanted it to have a street feel to it. On top of the kick pattern there's an 808 and a really busy live bass, which is great. The horns are also live. The potential problem with a record like this is that the drum and bass patterns are very busy, and there is a lot of frequency information that can cause a loss of dynamics and clarity. This was the real challenge for me. I was very concerned, and voiced this to Rodney and Beyoncé, that when the mastering engineer slapped his limiter on the mix to bring up the volume, all the low end would come up as well and you would lose all the bounce, which is the great thing about this record. So I ended up printing a couple of versions with the 808 pulled back, which is what they went with."

Bass processing included another URS Fulltec EQ (top), while Sony's Oxford Dynamics was used to compress the live bass and Waves' Renaissance Compressor (bottom) was used to duck it every time the kick drum hit."Basically, this song is a take on what Quincy Jones did with pre-Thriller Michael Jackson. Beyoncé really wanted it to have a street feel to it. On top of the kick pattern there's an 808 and a really busy live bass, which is great. The horns are also live. The potential problem with a record like this is that the drum and bass patterns are very busy, and there is a lot of frequency information that can cause a loss of dynamics and clarity. This was the real challenge for me. I was very concerned, and voiced this to Rodney and Beyoncé, that when the mastering engineer slapped his limiter on the mix to bring up the volume, all the low end would come up as well and you would lose all the bounce, which is the great thing about this record. So I ended up printing a couple of versions with the 808 pulled back, which is what they went with."

Drums: URS Fulltec EQ, Sony Oxford Transient Modulator, Smart C2 compressor

"There's something that sounds like a loop, but it's a hi-hat pattern that I put through some distortion to make it lo-fi and give it more movement. Rodney programs things like a drummer, so at any time there may be extra fills or patterns that change slightly, so I had to treat it like a live drummer, which was a blast for me. On the screenshot you can see that there are five kick drums. Rodney may program one all the way down, and then trigger other ones to get the feel he's after. But there'll be slight variations as some of them drop out in places, giving it a different feel. I have a dirty kick, a clean kick, and one that's more like a click. If one drops out, it changes things for just one beat and makes it sound more like a live drummer, as he never hits things exactly the same every time.

"The problem for me was to make that pattern fit with the bass and the 808, and they were long 808 hits — they carried over a couple of beats. So I EQ'd the 808 to leave only the very low end, and then put a gate on it that I triggered from one of the kicks that played the whole time, so that it only hits when the kick hits. Then, by shortening the release on the gate, I shortened the length of each 808 kick. This cleaned up the low end and also made space for the bass to move. It's such a great bass line that I actually EQ'd the bass a little higher than I normally would on an R&B record, so it would have some more presence. It is really moving the song. Obviously I had enough low end in the kick drums, so the record is not lacking in low end.

"If this record had been mixed totally in the box, you would have seen more plug-ins on it, but here's a sampling of what I do. I normally use the URS EQ on kick drums, typically boosting at 30 or 60 cycles. I'm cutting at 300 to create space for the bass guitar. I'm boosting twice at 5k, once with a bell and once with a shelf... that's an example of me just turning knobs until it sounds good! It's what gives the kick its snap.

Waves' PS22 stereo spreader helped to give the mono piano track some width.

Waves' PS22 stereo spreader helped to give the mono piano track some width.

Beyoncé's vocals were treated with hardware compression and EQ; one take was lightly de-essed with the Waves De-Esser, while the other was matched to it tonally using Sony's Oxford EQ. Line 6's Echo Farm was used as a ducking delay behind the lead vocal."The Sony Oxford Transient Modulator now replaces the Transient Designer in my rack. The plug-in tailors the envelope of the sound — the 0.20 ratio setting adds attack to the kick drum. I use the same effect on the finger snap. It changes the envelope. I also use this plug-in a lot on acoustic guitars. In cases where they're just playing rhythm and they are too 'plucky', I can slide that back a bit and take some of the attack off, without using compression. I do that a lot. It's also to do with the issue of apparent loudness. If you make the attack harder, something will sound louder. It will cut through the mix without having to add additional volume, and you don't get a build-up of EQ or phase shift either.

Beyoncé's vocals were treated with hardware compression and EQ; one take was lightly de-essed with the Waves De-Esser, while the other was matched to it tonally using Sony's Oxford EQ. Line 6's Echo Farm was used as a ducking delay behind the lead vocal."The Sony Oxford Transient Modulator now replaces the Transient Designer in my rack. The plug-in tailors the envelope of the sound — the 0.20 ratio setting adds attack to the kick drum. I use the same effect on the finger snap. It changes the envelope. I also use this plug-in a lot on acoustic guitars. In cases where they're just playing rhythm and they are too 'plucky', I can slide that back a bit and take some of the attack off, without using compression. I do that a lot. It's also to do with the issue of apparent loudness. If you make the attack harder, something will sound louder. It will cut through the mix without having to add additional volume, and you don't get a build-up of EQ or phase shift either.

"I also used my Alan Smart C2 compressor on the drums. It has something called Crush mode, which adds field-effect transistor distortion. I'm a big fan of using distortion, in small amounts. Tubes distort more harmonically, whereas transistors and Class-A stuff is more aggressive, which is why I think many guys still like to mix on the SSL 4000 — those consoles are always just shy of distorting. It adds to the overall aggression of the mix. So what I did on 'Déjà Vu' was feed all the drums into the Alan Smart, set the attack very slow, so all the transients get through, but set the release time very short, so that the dynamics of the drums are changed, and finally press the Crush button to add some aggression. During the mix I played the uncompressed drums side-by-side with the compressed drums, and I rode the compressed drums in and out depending on the section of the song. You can lift your chorus by giving it a different dynamic feel."

Bass: URS Fulltec EQ, Sony Oxford Dynamics, Waves Renaissance Compressor

"In addition to the live bass there's also a sub-bass, like a Moogerfooger kind of thing. I didn't use a lot of it, as it was just too much with the kick drum and the 808. The challenge was to get dynamics to happen with all these different elements going on in the low end. [The track labelled] 'Bass 4.02' is the live bass — the numbers probably refer to it being a fourth take. You can see how I use the URS EQ and the Oxford compressor/limiter on it. They are acting like you would expect them to. I pressed the 'Warmth' button on the Oxford to generate some harmonics and create presence and make the bass cut through. The [Waves] Renaissance Compressor is triggered by the kick drum. I often do this when the kick drum is being stepped on by the bass. So every time the kick hits, the bass ducks 2dB or so just for a moment. When you have a bass that's as prominent as on this record, you can't do too much."

Piano: Waves PS22

"There's a jangly piano going through the whole song. It's in mono and I put it through the Waves PS22 spreader to widen its stereo image. With most pop records you have so much information going on, but with this track, as busy as it is, it's actually pretty empty. There's not much playing all the time, only the drums, bass and the jangly piano. By widening the image of the piano I was also able to make more room for the lead vocal in the middle."

Vocals: Waves De-Esser, Line 6 Echo Farm, Sony Oxford EQ, Avalon 2055 EQ, Pendulum 6386 compressor

Jason Goldstein's preferred reverb plug-in is TC Electronic's VSS3."'BLD1C001', track 24, is the lead vocal, which has just a bit of de-essing on it. The VxFx is the Echo Farm delay you hear on her lead vocal. I use the dynamic stereo delay to add a bit of depth and character and spread to the vocal. Dynamic delays are often called ducked delays, because they will 'duck' out of the way, coming up only at the tail end of words and phrases. I almost never use a straight delay, unless it's as an obvious effect. I also used the Avalon 2055 EQ and my Pendulum Audio compressor on Beyoncé's vocals, because she can sometimes sound a little too strident and aggressive, and the tube compressor smooths things out a little bit and takes off some of the edge in those sections. Track 23 is the ad-lib track, on which I have the de-esser, which goes out to the Avalon 2055, which hits my Pendulum compressor, and then the board. Beyoncé must have done vocal takes on two different days, and one take goes to audio 17, where I use the Oxford EQ to compensate for the differences."

Jason Goldstein's preferred reverb plug-in is TC Electronic's VSS3."'BLD1C001', track 24, is the lead vocal, which has just a bit of de-essing on it. The VxFx is the Echo Farm delay you hear on her lead vocal. I use the dynamic stereo delay to add a bit of depth and character and spread to the vocal. Dynamic delays are often called ducked delays, because they will 'duck' out of the way, coming up only at the tail end of words and phrases. I almost never use a straight delay, unless it's as an obvious effect. I also used the Avalon 2055 EQ and my Pendulum Audio compressor on Beyoncé's vocals, because she can sometimes sound a little too strident and aggressive, and the tube compressor smooths things out a little bit and takes off some of the edge in those sections. Track 23 is the ad-lib track, on which I have the de-esser, which goes out to the Avalon 2055, which hits my Pendulum compressor, and then the board. Beyoncé must have done vocal takes on two different days, and one take goes to audio 17, where I use the Oxford EQ to compensate for the differences."

Reverb: TC M3000/VSS3 "The two TC VSS3 reverb plug-ins weren't actually on the record, but I added them, because their settings are exact replications of the hardware M3000 boxes that I used on those mixes. Since I've moved into the box, I'm using these TC reverbs. I like reverbs that are shorter, so the 'Stairway Plate' is my main reverb that went on a lot of stuff, and where I needed a longer reverb to fill in spaces, to throw in at the end of words or between sections, I used the 'Ambient Plate'. It's a feeling thing that's not necessarily audible."

For compressing the stereo backing vocals, Jason used Sony's Oxford Dynamics in dual-mono mode.

For compressing the stereo backing vocals, Jason used Sony's Oxford Dynamics in dual-mono mode.

Oxford Dynamics was used again for the bass on 'Irreplaceable'.

Oxford Dynamics was used again for the bass on 'Irreplaceable'.

Line 6's Echo Farm was used to generate eighth-note ducking delays on the 'Irreplaceable' lead vocal, and quarter-note delays on the backing vocals.

Line 6's Echo Farm was used to generate eighth-note ducking delays on the 'Irreplaceable' lead vocal, and quarter-note delays on the backing vocals.

On both tracks, the mix passed through Sony's Oxford EQ and Inflator plug-ins.Mix Buss: Sony Oxford EQ & Inflator

On both tracks, the mix passed through Sony's Oxford EQ and Inflator plug-ins.Mix Buss: Sony Oxford EQ & Inflator

"Aux 1 is my stereo buss. The Oxford three-band EQ adds whatever kind of EQ I felt the track needed — usually just a little bit of low and high end. The Oxford Inflator is one of those voodoo boxes that uses a little bit of compression and harmonic generation to allow you to play with the dynamics, or emulate tape compression. This is what makes my mixes sound louder. Like many mixers, I've had complaints that my mixes aren't loud enough. I could never figure out why that mattered, because by the time it got to mastering, it would be plenty loud. But these two plug-ins preserve the dynamics, so the mastering engineer has room to do his job."

'Irreplaceable'

Writers: Ne-Yo, Beyoncé Knowles, Mikkel Eriksen, Amund Bjørklund, Tor Erik Hermansen, E. Lind

Producers: Beyoncé Knowles, Stargate, Ne-Yo

"This song was really simple to mix. It was produced by Stargate and the sounds are really good and they all made sense, and there was lots of room for all the instruments. The drums mostly receive stock treatments with some board EQ. The acoustic guitars, which drive the whole song, were treated with the analogue flanger of the TC 1210, to sweeten the sound and give them a little bit more spread. I felt the song was a bit old-school; if Beyoncé wasn't singing this, you would think it was a pop or a rock song. So what I did, which I don't normally do, was to put an eighth-note slap echo on her vocal, at 341ms, the whole song through, using the Line 6 Echo Farm plug-in. I rode it so that when she sings louder, it gets out of the way, but when she sings softer, it comes up a little. The eighth-note delay gives the song a little bit of a push. There's nothing else doing eighth notes in the song.

"The other Echo Farm with the 682ms delay works on the background vocal master, just like the Oxford compressor/limiter. I usually combine the vocal takes of each background note, and then sub each of these different notes to an aux and compress and EQ them. I'll have the Oxford compressor set to double mono, with the link off, so the left and right side get compressed independently from each other. If one side gets significantly louder the compressor will grab it and pull it down a little, but not taking away the natural feel. The Oxford compressor/limiter is great. In the Classic setting, half the controls are turned off and it emulates the LA2A. The linear mode acts more like an 1176. The Warmth button adds harmonics and gives it presence, and I use that a lot.

"I use the Oxford also on the bass, but in a completely different setting. I didn't use the Warmth setting on this record, because there was already enough presence in the bass, but you can see that the attack is turned all the way up and the release is basically as quick as it can go. It's a very heavily compressed sound and it really brings up presence — you can hear all the notes. If it's played and recorded well you don't have to worry about that bringing out the negative artifacts as well.

"Just like on 'Déjà Vu', aux 1 is my stereo buss, and I'm using the Oxford EQ and Inflator. From the aux track it goes directly to Pro Tools, where I will print it at 44.1kHz/24-bit, and from there I make 24-bit CD masters that go to the mastering guy."

You Still Need A Studio

Despite the fact that Jason Goldstein now mixes entirely 'in the box', he still makes use of top studios, like Sony Music Studios in New York. "You still need the acoustics of a studio," he explains. "There is no substitute for a good-sounding and well-designed space. Plus Pro Tools rigs will sometimes crash, and it's nice to have the client service available at a major studio. There's also the vibe factor. Because of the kind of music that I do, the 'wow' factor is important, so I need big speakers. Clients like to be in rooms like at Sony with $60,000 Augsperger speakers, and where there's a lounge with a flat-panel TV. I now use the SSL 9000 at Sony just as a big monitoring board, but clients don't care whether I use it or not — they just want to be in a big studio."

But if Goldstein is paying lots of money for one of the world's leading studio facilities with a top-flight SSL included, why not use it? "There are two primary reasons," replies Goldstein. "Until recently, I honestly did not think that I could get the same quality out of the box. This was not so much to do with digital summing or resolution issues as that I couldn't get the same quality of effects from plug-ins as from outboard gear. But over the last couple of years manufacturers have come up with new plug-ins that mean that I'm totally cool with the way everything sounds. In fact, in some respects plug-ins now sound better.

"Over the last year I've found replacements for all my outboard gear. The URS EQs are brilliant for general tone shaping. I'm not a big fan of plug-in parametric EQ, because you can set the Q so narrow that you get phase shifting. You get into a lot of trouble if you use parametrics on a lot of stuff: broader tone shaping is just more musical. URS also have excellent API/Neve emulation, which I don't think sounds like API or Neve, but it sounds great anyway. I like [Sony] Oxford plug-ins a lot, especially for vocals. Their compressor/limiter is great. I also like the new Waves SSL compressor, which is my new drum sub compressor, for which I used to use the Alan Smart in the past. Digidesign's Impact is pretty good, too. You have to work a little harder, because it doesn't have the transistorised distortion in it. But you can add your own distortion, using Amp Farm, and get the same effect. I'm also using the Cranesong Phoenix plug-in a lot. It's the best tape emulator I've heard so far.

"The main problem I had for a long time was that I was unable to get the same quality from in-the-box reverb. I couldn't figure out why this was, because most reverbs are digital, so why couldn't they just put the same algorithms in a plug-in? Then you realise that a hardware box can be $3000 and a plug-in just $600. The Lexicon 960 is $10,000, and as great as it sounds, it's still only an algorithm, and computers today have enough capacity to run anything. Only during the last year have the plug-in manufacturers finally come up with good-quality in-the-box reverbs. If your reverb is not of good enough quality, it muddies the whole record up, and you may not realise it until it is too late. I'm not a fan of cloudy, mid-range reverb, nor of the big wash reverbs of the 1980s. I like clarity. I don't want to actually hear reverbs. I felt that a lot of plug-in reverbs sound like an effect. But you can now throw tons of TC VSS3 plug-in reverbs on things, and it will just feel bigger. I used to use the PCM70 a lot, which sounds dirty and ties things together. A little bit of PCM70 used to go on about everything I did, on a tiled room setting, which is a very small room. I have now found an emulation for that too. I tweaked a TC Electronic M3000 program called 'Tight & Natural', adding some high end and playing around with the delay."