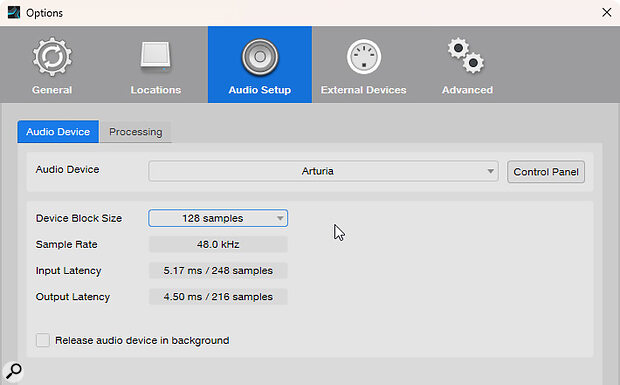

The Audio Setup screen is where you select your audio interface and Device Block Size, or buffer size. This will determine your ‘round‑trip’ latency.

The Audio Setup screen is where you select your audio interface and Device Block Size, or buffer size. This will determine your ‘round‑trip’ latency.

We show you how to get started recording audio in Studio One.

In recent workshops, we’ve got down to the basics of recording, editing and working with MIDI. Now it’s time to turn our attention to audio. Recording sound is a primary function of any DAW, and I think it’s good to go back to the original concepts. You might find that you’ve been doing it wrong all this time, or perhaps can find more efficient ways of achieving your aims. Studio One continues to evolve, so the tools and processes we use all the time can change. You might even find something you didn’t know existed that will improve your workflow.

From the Studio One welcome page, you can do a little bit of configuration on your audio interface. Well, I say configuration, but all you can really do is choose the interface and set the buffer size (or Device Block Size as Studio One likes to call it). Sample rate settings and input/output configurations are managed elsewhere, and you can’t get to them at this point. So, first make sure your audio interface is selected.

For audio recording, it’s likely that we’re going to want to monitor our audio through the Studio One mixer, and perhaps through its plug‑in effects. This requires a low input and output latency, which means a low Block Size setting. You are aiming for a round‑trip latency of less than 10ms or so. The ‘round trip’ latency is the input latency plus the output latency. When you plug in your guitar, the audio interface buffers the signal coming in; that causes a short delay, which is the input latency. It then goes through Studio One and maybe through the Ampire plug‑in and back to the audio interface, where it’s buffered again before going to your speakers; that’s output latency. Those two things (the ‘round trip’) contribute to the total amount of latency you experience. Anything more than 10ms and you’ll begin to hear the delay to the audio when monitoring on headphones.

Lowering the latency will make monitoring feel snappier, but it also puts pressure on your computer’s processor. A Device Block Size of 128 or 64 samples should be a good compromise, allowing you to hear what you’re playing without distracting delay, and without hammering the CPU. Alternatively, we can use Direct Monitoring to bypass the Studio One mixer and avoid the buffering latency, and we’ll talk about that later.

Templates

Studio One comes with a wide range of templates that can help you get recording quicker.Now it’s time to create a song and get recording. Click on New at the top of the welcome page, and you’ll be presented with a list of helpful templates. I used to ignore these things, but for version 6 PreSonus have tidied them up, and I’m starting to appreciate the help. For this workshop, we’re going to select the Record Now template for a new audio recording. After you’ve clicked on it, more options will appear on the right side of the window. We can set it up as a single track, two tracks for vocal and guitar, or a full band.

Studio One comes with a wide range of templates that can help you get recording quicker.Now it’s time to create a song and get recording. Click on New at the top of the welcome page, and you’ll be presented with a list of helpful templates. I used to ignore these things, but for version 6 PreSonus have tidied them up, and I’m starting to appreciate the help. For this workshop, we’re going to select the Record Now template for a new audio recording. After you’ve clicked on it, more options will appear on the right side of the window. We can set it up as a single track, two tracks for vocal and guitar, or a full band.

The Guitar/Vocal and Full Band templates are very interesting. They set up multiple channels for recording, and add a selection of effects and dynamics processing. There’s also an Impact drum machine loaded for the Guitar template, and for the full band you get seven channels set up for drums, all squirrelled away in a folder track. We’ll deal with those in more detail in another workshop, as there’s much to go through and probably lots to learn about setting up tracks, inserts and routing. For now, let’s keep things simple and opt for a Single Track.

I should point out that the template doesn’t default to the sample rate set by your audio interface, so you should check and ensure it’s set correctly. You may have other systems in your computer that are using the audio engine, and swapping sample rates unexpectedly is rarely good.

Once we’re in Studio One we get treated to the new internal tutorial system. It introduces the template and then gives you a tour over the course of five or six screens. While it doesn’t let you do anything while it’s running, it highlights exactly what you need to do to start recording and is spookily similar to what we’re talking about.

Audio Tracks

The template gives us our one track ready for recording. It also loads an Input Channel and a channel strip for the track into the mixer console. The inspector isn’t open and the layout is nice and clean, so we can focus on dealing with that audio track.

We first need to check that the input and output options in Studio One correspond correctly to the actual inputs and outputs on our interface. Click on the down arrow next to where it says Input 1 on the audio track header, and select Audio I/O Setup. In this window, we can see all the physical inputs that our audio interface presents, listed on the horizontal axis of a grid from left to right. The vertical axis displays all the software inputs that Studio One has created, and the intersections within the grid show where the two match up.

The Audio I/O Setup window lets you assign your audio interface’s physical inputs and outputs for use in Studio One.

The Audio I/O Setup window lets you assign your audio interface’s physical inputs and outputs for use in Studio One.

By default, Studio One will create a couple of inputs and assign them to the first couple of physical inputs. These may not be the ones you intend to use, but you can reassign them, rename them or create additional Studio One inputs. Simply click in the grid to connect a Studio One input to a physical input. There’s also an Output tab where you can do precisely the same thing with the output configuration. This means that when you’re assigning inputs to tracks in Studio One, you don’t have to browse through all the physical inputs of your interface directly. Instead, you select ‘virtual’ inputs you created, named and assigned to those physical inputs.

In the screenshot, I’ve called the first Studio One input Vocal, and I’ve assigned it to the first physical input on my Arturia Audiofuse, where I have a mic plugged in. I’ve plugged my guitar into the second input, and named the corresponding Studio One input Guitar. The output from my synth rig goes into inputs 3 and 4 on the interface, and so I’ve created a stereo input for those.

If we monitor through Studio One by enabling the Monitor button, we’ll be able to use effects that we can hear as we sing or play.

Monitoring

Back to our track in the arrange window, and next to where it says Track 1 are four buttons. M (Mute) and S (Solo) should be familiar; we’re not interested in those right now. The other two are Record Enable and Monitor. If we want to record onto that track through the selected input, Record Enable needs to be turned on. That’s easy, right? The Monitor button determines how we hear our input signal. We can either monitor what we’re playing or singing through Studio One, or do it outside of Studio One.

Let me explain. Normally speaking, when recording an instrument or your voice, you want to be able to hear what you’re doing. When using microphones, you’ll need to listen using headphones so you don’t get feedback and so that none of the playback music gets picked up by the microphone. With your headphones on, it’s difficult to hear your own singing or the twanging of your guitar unless that signal is returned back to your headphones. This is called foldback, or live input monitoring.

Here, Track 1 (the vocal track) is in Record Enable mode (the red button below Mute), and has input monitoring enabled (blue button). The large meter on the Input Channel at the left shows that the level is somewhere around the ‑12dB mark.If we monitor through Studio One, by enabling the Monitor button, we’ll be able to use effects that we can hear as we sing or play. You could, for example, add reverb to a vocal, or use Ampire on your guitar. There’s nothing to stop you from adding or changing these effects later, but hearing them while recording can be very useful. The downside is that you will encounter the full round‑trip latency of your system. If that’s too large, your monitoring will sound weird and laggy, which won’t help your performance.

Here, Track 1 (the vocal track) is in Record Enable mode (the red button below Mute), and has input monitoring enabled (blue button). The large meter on the Input Channel at the left shows that the level is somewhere around the ‑12dB mark.If we monitor through Studio One, by enabling the Monitor button, we’ll be able to use effects that we can hear as we sing or play. You could, for example, add reverb to a vocal, or use Ampire on your guitar. There’s nothing to stop you from adding or changing these effects later, but hearing them while recording can be very useful. The downside is that you will encounter the full round‑trip latency of your system. If that’s too large, your monitoring will sound weird and laggy, which won’t help your performance.

The alternative is to use Direct Monitoring. This routes the input directly to the output within the audio interface, thus bypassing buffer latency. But as what you’re hearing isn’t passing through Studio One, it isn’t going through any plug‑in effects you want to use either. Direct Monitoring is probably the best choice if you are familiar with running external gear or mixers and generally handling your audio outside the computer prior to recording.

Input Level

Once you’ve sorted out how you will hear yourself, you need to get the right level into Studio One for recording. Conventional wisdom says that you should aim to have the highest peaks reach roughly ‑12dBFS. FS stands for ‘full scale’, so this is 12dB below the largest value the system can accommodate. This gives enough headroom for incidental bursts of performance energy, while keeping the signal far enough above the noise floor to ensure that hiss won’t be a problem.

Your audio interface may provide some metering, but it’s usually quite rudimentary. Fortunately, Studio One has some lovely fat Input Channel meters that will help you to hit the right level. In the template, the Input Channels are already open in the console. Regardless of your monitoring settings, these will show the incoming level.

While singing or playing, adjust the gain controls on your audio interface so that the loudest parts reach the ‑12dB mark, which is the first line in the upper quarter of the meter. The Input Channel also has a gain control, which ranges from ‑24dB or +24dB. This can be useful for adding further gain if your mic preamp can’t deliver enough, but it can’t negate the effects of recording at too high a level and clipping the A‑D converter.

Input Effects

You may have noticed that the Input Channel also has insert points. These give you access to all the same insert presets, dynamics processing and VST effects that are available on other channel types, but the key difference is that any effects inserted here will be printed onto the recorded track. So if you load up Ampire on the guitar Input Channel, the recorded guitar track will capture the output of Ampire. It would be like recording through an external effects unit before the signal reaches the interface.

Whether this is useful depends on how you like to work. One of the key things DAWs did was provide us with a safety net by making effects non‑destructive, as they are when used on other channels, so that we could change them without having to re‑record. But sometimes committing to a sound is helpful!

When you’re ready to go, make sure the Record Enable button is lit and hit Record on the transport bar. We’ll talk about what happens after that in the next workshop...