A simple, catchy tune with a funky rhythm may be all you need to create a highly commercial horn hook — but harmony is also an essential ingredient in brass arrangements.

A great horn arrangement can galvanise a record, and Beyoncé Knowles knows it. When asked in a 2004 MTV interview what made her ‘Crazy In Love’ song so lively and infectious, the Texan singer summed it up succinctly: “It’s the horn hook.” Earlier this year, when the same TV channel sought expert advice on the question “Why Is ‘Uptown Funk’ so catchy?” (a topic which never fails to provoke heated debate in the House of Lords), UK musicologist Joe Bennett opined, “The big release, the most exciting bit of the song, is the brass riff.”

The horn hook on ‘Crazy In Love’ is actually a sample of a lick from the Chi-Lites’ 1970 song ‘Are You My Woman? (Tell Me So)’. Like all good stick-in-your-head riffs, the horn part is deceptively simple — a triumphant-sounding unison phrase played twice, the second time with an altered last note, over a standard C-major to A-minor chord sequence propelled by a driving, funky beat. Despite initial concerns that this iconic sample might be regarded as old-fashioned, Beyoncé has since praised its crucial contribution to the song’s runaway success.

It’s unlikely that Mark Ronson had any such qualms when co-producing ‘Uptown Funk’ with Bruno Mars: since the aim was to make a classic funk song, its seventies-inspired instrumental horn break comes as no surprise. A jaunty four-note lick parps out three times in quick succession, followed by an offbeat stab and a short descending run; after a bar’s rest, the vocal hook ‘Don’t believe me, just watch’ is answered by a staccato, machine-gun-like burst of six repeated notes (doubled by snare drum) — this short call-and-response is repeated three times at the end of the break. I’ve notated the horn part in  The ‘Uptown Funk’ instrumental break horn line, transcribed by Dave Stewart. The part focuses on rhythm, with only four notes used in the melody — note how the first ‘F D C D’ phrase is played three times in the first bar, with the second iteration falling on the offbeat between beats two and three. This passage starts at 2.21.diagram 1 and, as you can see, its rhythmic mini-phrases are classic funk figures, animated, catchy and danceable. The horns are voiced in time-honoured style, with saxes and trombone doubling the high trumpet part an octave down, underpinned by an alternating Dm7 to G7 chord sequence.

The ‘Uptown Funk’ instrumental break horn line, transcribed by Dave Stewart. The part focuses on rhythm, with only four notes used in the melody — note how the first ‘F D C D’ phrase is played three times in the first bar, with the second iteration falling on the offbeat between beats two and three. This passage starts at 2.21.diagram 1 and, as you can see, its rhythmic mini-phrases are classic funk figures, animated, catchy and danceable. The horns are voiced in time-honoured style, with saxes and trombone doubling the high trumpet part an octave down, underpinned by an alternating Dm7 to G7 chord sequence.

Two’s Company...

I hesitate to suggest that the two aforementioned worldwide smash hits might be lacking in any way, but from a strictly musical point of view, it’s true to say that their horn arrangements rely mainly on rhythmic syncopation, with little or no melodic development. That’s not meant as a criticism — these parts are highly effective, and to elaborate them would only dilute their impact. However, a good brass arranger needs more strings to his or her bow than funky licks and a catchy tune: at some point, you’ll also need to consider the vital ingredient of harmony, that mysterious, beautiful musical element that can transform base metal into gold.

Because the highest part in a horn arrangement defines the melody, catches the ear and gives the music its character, the convention in brass arranging is to write harmonies underneath a top line. (This isn’t a hard and fast rule, but bear in mind that if you write an upper harmony, you’re effectively creating a new melodic top line, with the original melody relegated to a supporting role!) Applying the ‘harmonies underneath’ approach to the rising line shown in  A simple rising line written over an ascending chord progression of D, E-minor, F and G.diagram 2 (written over an ascending chord progression of D, E-minor, F and G) gives us the simple thirds harmonisation depicted in diagram 3

A simple rising line written over an ascending chord progression of D, E-minor, F and G.diagram 2 (written over an ascending chord progression of D, E-minor, F and G) gives us the simple thirds harmonisation depicted in diagram 3 Diagrams 3-6 show how adding a lower part (marked in red) to a melody line creates simple harmonisations. — the lower harmony part is marked in red. Chord names are written above the stave, with note names displayed underneath.

Diagrams 3-6 show how adding a lower part (marked in red) to a melody line creates simple harmonisations. — the lower harmony part is marked in red. Chord names are written above the stave, with note names displayed underneath.

If you’re thinking, “Oh no, not another music lesson”, please bear with me — I’ll get back to the juicy funky stuff before long, but want to give a few basic pointers in horn chord construction which will be useful in many different musical situations. Feel free to skip the music theory if you already know it, but if not, rest assured that making an effort to get your head round it will be time well spent — far from being a dangerous thing, a little musical knowledge is actually extremely useful!

Staying with the same chord sequence, we can move the melody line up to the notes of A, B, C and D (each of which forms a fifth interval over the root note of its chord). As in the previous example, this can be simply harmonised by adding thirds underneath, as shown in diagram 4. Pursuing the same logic, we can move the top line up further to play the octave of each chord (ie. a high D, E, F and G), but finding a lower harmony for that is less straightforward: adding thirds underneath doesn’t work in this case, and a harmonisation of A, B, C and D (as in diagram 5) gives us a row of fourths, a rather plain and austere-sounding interval. Unless you particularly want that effect, a better solution would be to keep the same lower harmony of F#, G, A and B used in diagram 4, which creates an interval of a sixth between the harmony and melody notes (see diagram 6).

Thirds and sixths enjoy a special musical relationship (which becomes evident when you compare the note names in diagrams 3 and 6), and share a similar, sweet, easy-on-the-ear sound. Choosing between them is purely a matter of taste: being the most ubiquitous harmony in popular music, thirds can sound trite and naüve if overused, but they work well in punchy, upbeat rhythmic passages, and their unpretentious simplicity fits the cheerful DIY ethos of music styles such as ska pop-punk. The wider sixths voicing works well in slower music and spacey ballads (the horn intro on the Exodus / Kaya Demos version of Bob Marley’s ‘Natural Mystic’ is a good example). But ultimately, there are no rules — you should write what you think sounds best, and feel free to mix and match different harmony voicings throughout a song.

Three’s A Chord

While many bands get by with two horn players, it takes three to complete the basic chordal picture. Diagram 7 The three possible close voicings of a three-note D-major chord. Middle C is marked in blue. shows the three possible close voicings of a simple three-note D-major chord. We can expand the voicings by dropping the second note from the top down an octave, as in diagram 8

The three possible close voicings of a three-note D-major chord. Middle C is marked in blue. shows the three possible close voicings of a simple three-note D-major chord. We can expand the voicings by dropping the second note from the top down an octave, as in diagram 8 You can use the ‘drop 2’ method to introduce wider intervals into chord voicings. — this vertical re-spacing introduces wider fifths and sixths intervals, which has the effect of breathing air into the chord. Though an unsupported fifth (such as the A and D in the last chord) can sound stern and serious, placing the third (F#) in the bass creates a lovely, lyrical sound.

You can use the ‘drop 2’ method to introduce wider intervals into chord voicings. — this vertical re-spacing introduces wider fifths and sixths intervals, which has the effect of breathing air into the chord. Though an unsupported fifth (such as the A and D in the last chord) can sound stern and serious, placing the third (F#) in the bass creates a lovely, lyrical sound.

In jazz circles, this method of expanding chord voicings is known as ‘drop 2’. While it’s a musically sound technique, I wouldn’t advise that you apply it every time you need a wider voicing: a more creative, open-minded approach would be to experiment with different wide intervals on a keyboard until you find some agreeable note combinations. Whether you’re working on musical details or simply trying to dream up basic ideas, trial and error is an important part of the creative process. Embrace your mistakes — with a little minor readjustment, they often lead to exciting new possibilities!

Although you can get a fair bit of mileage out of simple major and minor chords, it would be sad to limit your horn charts to those basic harmonies. Suspensions such as ‘sus 4’ and ‘sus 2’ chords can spice up an arrangement, and sound great played on three trumpets — the example in diagram 9 ‘Sus 4’ and ‘sus 2’ chords sound great played on three trumpets — this example shows those chords in the key of A, resolving to a major triad in the third bar. shows those two chords in the key of A, resolving to a major triad in the third bar. As an alternative to block chord changes, you can resolve suspensions in an interesting way by introducing an inner contrapuntal movement, as illustrated in diagram 10.

‘Sus 4’ and ‘sus 2’ chords sound great played on three trumpets — this example shows those chords in the key of A, resolving to a major triad in the third bar. shows those two chords in the key of A, resolving to a major triad in the third bar. As an alternative to block chord changes, you can resolve suspensions in an interesting way by introducing an inner contrapuntal movement, as illustrated in diagram 10. Suspensions can be resolved in an interesting way by means of an inner contrapuntal movement, marked in red.

Suspensions can be resolved in an interesting way by means of an inner contrapuntal movement, marked in red.

Miles Ahead

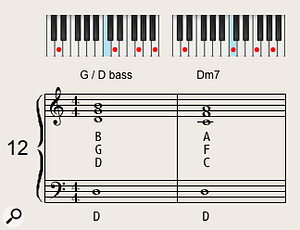

Another simple three-note chord that sounds good on horns is the minor seventh, voiced as in diagram 11 A simple three-note voicing of a minor-seventh chord. with horns playing the top three notes. This chord voicing has a cool, slightly jazzy flavour, and shifting it up a tone and back down again over a held bass note (as shown in diagram 12)

A simple three-note voicing of a minor-seventh chord. with horns playing the top three notes. This chord voicing has a cool, slightly jazzy flavour, and shifting it up a tone and back down again over a held bass note (as shown in diagram 12) Shifting the minor-seventh voicing up and down a tone over a held bass note creates a nice chordal movement. creates a nice chordal movement. A version of this occurs in funkmeister James Brown’s 1967 single ‘Cold Sweat’. The song has an interesting lineage — Brown’s colleague and co-writer Pee Wee Ellis recalls, “I was very much influenced by Miles Davis and had been listening to ‘So What’ six or seven years earlier, and that crept into the making of ‘Cold Sweat’. You could call it subliminal, but the horn line is based on Miles Davis’ ‘So What.’

Shifting the minor-seventh voicing up and down a tone over a held bass note creates a nice chordal movement. creates a nice chordal movement. A version of this occurs in funkmeister James Brown’s 1967 single ‘Cold Sweat’. The song has an interesting lineage — Brown’s colleague and co-writer Pee Wee Ellis recalls, “I was very much influenced by Miles Davis and had been listening to ‘So What’ six or seven years earlier, and that crept into the making of ‘Cold Sweat’. You could call it subliminal, but the horn line is based on Miles Davis’ ‘So What.’

James Brown’s ‘Cold Sweat’ does indeed bear a resemblance to Miles’ ‘So What’ — even the title sounds similar! Although both are based on the simple two-chord movement shown above, ‘So What’ famously employs a fourth interval under the right hand chords (notated in diagram 13), The cool, sophisticated jazzy voicing used in Miles Davis’ ‘So What’ introduces a low fourth interval under the minor-seventh chords. creating a super-cool, sophisticated jazzy sound. The ‘Cold Sweat’ version is simpler; as you can see in diagram 14,

The cool, sophisticated jazzy voicing used in Miles Davis’ ‘So What’ introduces a low fourth interval under the minor-seventh chords. creating a super-cool, sophisticated jazzy sound. The ‘Cold Sweat’ version is simpler; as you can see in diagram 14, A simplified, funky treatment of the minor-seventh chord movement, as featured in James Brown’s ‘Cold Sweat’. it uses a higher, triadic inversion of the chords and dispenses with the E to D movement in the bass, replacing it with a repeated funky bass line in D.

A simplified, funky treatment of the minor-seventh chord movement, as featured in James Brown’s ‘Cold Sweat’. it uses a higher, triadic inversion of the chords and dispenses with the E to D movement in the bass, replacing it with a repeated funky bass line in D.

Both of these horn licks get their rhythmic drive from the characteristic ‘long-short’ phrasing I mentioned in my previous article; if you play both chords the same length, the feel evaporates! The ‘Cold Sweat’ riff is a great, simple pattern which could be repeated by horns behind a solo, while the fourths-based harmony of Miles Davis’ chords is worth exploring if you want to take your brass arrangements into more adventurous territory.

Expressive Techniques

OK, enough on harmony already. It’s important, obviously, but it’s a huge subject, and we need to consider other matters such as, how you add musical expression to sampled or synth brass instruments.

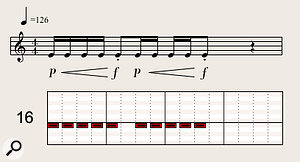

One simple way is via the use of volume swells, or ‘crescendos’ as they’re known in the trade. A regular crescendo note starts quietly and grows in volume, an exhilarating sound when performed by horns — as the volume of the instrument increases, so its tone opens up from a warm hum to a bright, commanding shout. The reverse process, a ‘diminuendo’ from loud to soft, is also very effective. You can hear both at work in KC & the Sunshine Band’s disco classic ‘That’s The Way (I Like It)’, starting in the verse section at 0.35; the horns play a crescendo and diminuendo on alternate bars, a mobile and engaging dynamic effect. So you can see how it looks in a score, I’ve notated this dynamic movement (using a melody line of my own!) in diagram 15. Horn chords with alternating crescendos and diminuendos produce a mobile and engaging dynamic effect — here’s how the ‘hairpins’ look in a score!

Horn chords with alternating crescendos and diminuendos produce a mobile and engaging dynamic effect — here’s how the ‘hairpins’ look in a score!

If you’re looking for something more animated, applying short crescendos to repeated, fast staccato trumpet notes (as shown in diagram 16) Applying short crescendos to repeated, fast staccato trumpet notes is a great dramatic device. is a great attention-grabbing device. A good example of it occurs at 2.37 in Jerry Hey’s terrific horn arrangement for the Tubes’ ‘Tip of My Tongue’ — it’s also worth listening out for the amazing ‘raucous unpitched glissando’ horns effect which occurs shortly beforehand. Although such dramatic techniques may be beyond the remit of straight pop arranging, they could be just the thing you need to energise a film cue.

Applying short crescendos to repeated, fast staccato trumpet notes is a great dramatic device. is a great attention-grabbing device. A good example of it occurs at 2.37 in Jerry Hey’s terrific horn arrangement for the Tubes’ ‘Tip of My Tongue’ — it’s also worth listening out for the amazing ‘raucous unpitched glissando’ horns effect which occurs shortly beforehand. Although such dramatic techniques may be beyond the remit of straight pop arranging, they could be just the thing you need to energise a film cue.

A nice variant on straight volume swells is the forte-piano crescendo — that may sound like a contradiction in terms, but what it actually means is a loud, accented long note which goes quiet immediately after the initial accent, then swells up again in a crescendo. Combining the rhythmic impact of the accent with the dynamic expression of the crescendo swell, this style works particularly well on horns, and has become a fixture in pop brass writing.

You can simulate brass swells and fades on a synth by sweeping the low-pass filter cut-off frequency (not to be confused with filter resonance, which makes the sound thinner) of a brass patch. Some modern workstations assign a front-panel knob to this function: Jonah Nilsson of Dirty Loops uses the technique to play some great, powerful brass-like swells on his Korg X50 in the trio’s song ‘Hit Me’. It doesn’t sound much like real horns, but in the context of this synth-driven track, it works well — using real players would arguably have been overkill. As with the so-called ‘Minneapolis sound’ pioneered by Prince in the late ‘70s, Nilsson’s highly rhythmic synth playing features the syncopated stabs, accents and phrasing of funk horn riffs, demonstrating that in pop an artificial sound can be OK, providing the musical intent and spirit is right.

More realistic-sounding crescendos can be achieved by using samples, but it does involve a bit more legwork. Although some pop brass sample libraries supply played crescendos of different lengths, making them fit the timing of your track can be a head-scratcher. The current convention in sample libraries is for users to create their own volume swells and fades using special ‘dynamic cross-fade’ patches; these give you control of the crescendo’s timing by using the mod wheel to fade between the instrument’s dynamic layers, which can sound great on brass long notes.

The ‘forte-piano crescendo’ effect is harder to simulate. While few pop brass sample libraries contain this particular articulation, most of them do have straight forte-piano (fp) samples, so you can fake the style by layering an fp sample with a crescendo sample. I don’t own the library, but it appears that Native Instruments Session Horns Pro offers a more elegant solution by providing tempo-synced forte-piano crescendos played over two or four beats, which can be time-stretched if you need them to be longer or shorter.

Grace Under Pressure

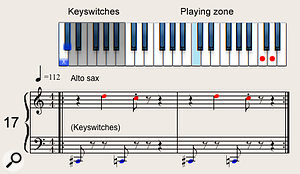

Small musical details can make all the difference to the realism of a sampled horn arrangement. Looking at the musical examples shown above, you’ll notice that the first chord of the ‘Cold Sweat’ lick in diagram 14 has grace notes on the front, each of which is a tone below its target pitch. I tried playing the top line as written on a synth using a sustained saxophone patch, but no matter how carefully I phrased it, the transition from the grace note to the main note sounded clunky. It became clear that a sampled solution was required.

Most pop brass libraries contain grace-note articulations but few offer a choice of interval — one notable exception is the Vienna Symphonic Library, which provides grace notes for every interval up to an octave. Although I’ve generally cautioned against using orchestral libraries for pop brass work, VSL’s saxophones are excellent, so I set about programming the top line for alto sax using the Vienna Instruments Pro player. This entailed creating a two-way keyswitch between a grace note patch and a sustained note patch, then playing the part as shown in diagram 17, Using keyswitches to switch between a grace note and a sustained note. The right hand plays the melody (red) and the left operates the keyswitches (blue). In this case, the low-C# keyswitch selects a grace-note patch, and the low C a sustains patch, as in diagram 18. with right hand playing the melody (marked in red) and left hand operating the keyswitches (marked in blue). The keyswitches (which are silent) triggered the patch change depicted in diagram 18,

Using keyswitches to switch between a grace note and a sustained note. The right hand plays the melody (red) and the left operates the keyswitches (blue). In this case, the low-C# keyswitch selects a grace-note patch, and the low C a sustains patch, as in diagram 18. with right hand playing the melody (marked in red) and left hand operating the keyswitches (marked in blue). The keyswitches (which are silent) triggered the patch change depicted in diagram 18, Diagram 18: The Vienna Symphonic Library provides grace notes for every interval up to an octave, which came in handy when we needed to program the saxophone top line in diagram 14. The ‘gr2’ patch name signifies that the grace note is a two-semitone interval. creating a smooth musical elision which sounded perfectly natural. Yes, that’s a lot of work for one tiny musical moment — but if 100 percent realism is your goal, this is what it takes.

Diagram 18: The Vienna Symphonic Library provides grace notes for every interval up to an octave, which came in handy when we needed to program the saxophone top line in diagram 14. The ‘gr2’ patch name signifies that the grace note is a two-semitone interval. creating a smooth musical elision which sounded perfectly natural. Yes, that’s a lot of work for one tiny musical moment — but if 100 percent realism is your goal, this is what it takes.

Pop Horns Are Go

Tom Walsh (foreground) with British trumpet legend Derek Watkins, the sound of James Bond, Tom Jones, Shirley Bassey, Kenny Wheeler’s big band, James Last and more.I’d like at this point to introduce UK trumpet player Tom Walsh: having earned his spurs as lead trumpet player with the National Youth Jazz Orchestra, Tom has worked with some of the UK’s top big bands and also played principal trumpet in orchestral settings with John Wilson and the RTE Concert Orchestra. A disciple of US horn-arrangement guru Jerry Hey, Tom says, “Thanks to the jazz arranging and composition tutelage I received at music college, and using Jerry’s writing as an influence, I got started on writing my first horn arrangements on top of existing pop tunes for practice, and ever since then I’ve been bitten by the bug!” I’ve included diagrams of two short extracts from one of Tom’s horn scores, which illustrate how some of the musical examples in this article can be put into practice in a pop arrangement.

Tom Walsh (foreground) with British trumpet legend Derek Watkins, the sound of James Bond, Tom Jones, Shirley Bassey, Kenny Wheeler’s big band, James Last and more.I’d like at this point to introduce UK trumpet player Tom Walsh: having earned his spurs as lead trumpet player with the National Youth Jazz Orchestra, Tom has worked with some of the UK’s top big bands and also played principal trumpet in orchestral settings with John Wilson and the RTE Concert Orchestra. A disciple of US horn-arrangement guru Jerry Hey, Tom says, “Thanks to the jazz arranging and composition tutelage I received at music college, and using Jerry’s writing as an influence, I got started on writing my first horn arrangements on top of existing pop tunes for practice, and ever since then I’ve been bitten by the bug!” I’ve included diagrams of two short extracts from one of Tom’s horn scores, which illustrate how some of the musical examples in this article can be put into practice in a pop arrangement.

The first, diagram 19, An extract from trumpet player Tom Walsh’s pop horn arrangement, showing the dynamic ‘forte-piano crescendo’ style in action. The parts are scored for (from top down) three trumpets, tenor sax and trombone shows the abovementioned ‘forte-piano crescendo’ dynamic in action. Scored for (from the top down) three trumpets, tenor sax and trombone, the instruments start on a unison note of D, with sax and trombone playing an octave below the trumpets. On the ensuing chord, trumpet one plays a high E, trumpet two takes the D a tone below that, and the third trumpet plays the A below the D, making a composite chord of Asus4. The sax and trombone strengthen the chord by doubling the lower two trumpet notes an octave down. Having hit an accent on the eighth-note between beats two and three, the horns quickly drop down in volume then play a crescendo swell over six beats, cutting off on the ‘and’ of beat four, an eighth-note before the end of the bar. This may seem an unimportant detail, but leaving that small gap creates a breathing space which increases the impact of the incoming chorus.

An extract from trumpet player Tom Walsh’s pop horn arrangement, showing the dynamic ‘forte-piano crescendo’ style in action. The parts are scored for (from top down) three trumpets, tenor sax and trombone shows the abovementioned ‘forte-piano crescendo’ dynamic in action. Scored for (from the top down) three trumpets, tenor sax and trombone, the instruments start on a unison note of D, with sax and trombone playing an octave below the trumpets. On the ensuing chord, trumpet one plays a high E, trumpet two takes the D a tone below that, and the third trumpet plays the A below the D, making a composite chord of Asus4. The sax and trombone strengthen the chord by doubling the lower two trumpet notes an octave down. Having hit an accent on the eighth-note between beats two and three, the horns quickly drop down in volume then play a crescendo swell over six beats, cutting off on the ‘and’ of beat four, an eighth-note before the end of the bar. This may seem an unimportant detail, but leaving that small gap creates a breathing space which increases the impact of the incoming chorus.

The second of Tom Walsh’s score extracts occurs in the song’s intro: it illustrates a typical horn arrangement technique, a unison phrase culminating in a chordal stab. As in the previous example, the three trumpets start off in unison, then divide to play the three notes of the final chord; the lower horns double the trumpet melody an octave down, then reinforce the chord with a pair of lower notes. By coincidence, the chord in question is the Miles Davis ‘So What’ voicing mentioned earlier, played up the octave in E-minor (though the bass line remains in D throughout the two bars). You can see this notated in diagram 20. Another Tom Walsh score extract, this one illustrating a unison melodic phrase culminating in a chordal stab — a typical horn arrangement technique. The ‘hat’ symbol on the phrase’s last note indicates a short, slightly accented articulation. Thanks to Tom for providing these extracts — we’ll be hearing more from him next month.

Another Tom Walsh score extract, this one illustrating a unison melodic phrase culminating in a chordal stab — a typical horn arrangement technique. The ‘hat’ symbol on the phrase’s last note indicates a short, slightly accented articulation. Thanks to Tom for providing these extracts — we’ll be hearing more from him next month.  The Broadway Big Band sample library contains jazz and big-band horns playing an extensive range of articulations.

The Broadway Big Band sample library contains jazz and big-band horns playing an extensive range of articulations. Amongst its other tricks, Native Instruments Session Horns Pro provides tempo-sync’ed forte-piano crescendos which can be time-stretched to the length you require.

Amongst its other tricks, Native Instruments Session Horns Pro provides tempo-sync’ed forte-piano crescendos which can be time-stretched to the length you require.

Coming Up

Next month I’ll look at all the elements that go into creating a successful brass arrangement, give a few more tips about how to get the most out of your brass samples, show you some more chords and take a peek into the musically rich world of big-band arrangement. Thanks for reading!

20 Assorted Brass Arrangements

Here are 20 pop, rock and funk brass arrangements dating from the ’60s to the present day, with notes on their points of musical interest. Spanning everything from simple pop-punk to arty, avant-garde atonalism, this eclectic selection shows how the simple founding principles of ’60s arrangements have evolved and diversified down the years. Certain songs are included merely in order to illustrate a particular arranging technique, but I recommend that would-be horn arrangers give them all a listen.

1. ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’ (the Beatles) 1967 — George Martin’s highly effective arrangement for four trumpets (which starts at 1.10) combines simple triadic chords and urgent rhythm stabs.

2. ‘Are You My Woman? (Tell Me So)’ (the Chi-Lites) 1970 — the original recording of the fabulous horns riff powering Beyoncé’s ‘Crazy In Love’, also features some great funky syncopated rhythm patterns at 1.51.

3. ‘25 or 6 to 4’ (Chicago) 1970 — this enigmatically titled song gains much of its character from a hooky, adventurous brass arrangement that finally grinds to a halt with five defiantly odd horn chords.

4. ‘Give Me Just A Little More Time’ (the Chairmen Of The Board) 1970 — proves that you don’t need more than three notes to write a catchy horns hook.

5. ‘Got To Get You Into My Life’ (Earth, Wind & Fire) 1978 — a jazzy 12/8 take on the Fab Four’s soul-flavoured tune, featuring a flash, brilliantly played arrangement with some startling ‘shake’ stabs.

6. ‘Burn This Disco Out’ (Michael Jackson) 1979 — a great arrangement by the legendary Jerry Hey, performed by the Seawind Horns.

7. ‘I Keep Callin’ (Al Jarreau) 1984 — another precisely played, funky and musically hip Jerry Hey chart. A masterclass in fitting horn parts round a vocal line.

8. ‘Can’t Get Enough’ (Supergroove) 1994 — a supremely efficient and economical horn arrangement helps propel this super-funky track by the engaging Kiwi band. Warning: contains humorous interjections.

9. ‘City Of Angels’ (the Generators) 1997 — energetic, uptempo ska pop-punk with a horns intro voiced in thirds, as explained in ‘Two’s Company’ earlier.

10. ‘Museum Of Idiots’ (They Might Be Giants) 2004 — a powerful brass arrangement, written along classical lines and played with great gusto, turbo-charges this touching and quirky little song.

11. ‘Some Skunk Funk’ (the Brecker Brothers) 2005 — this manically fast, intensely exciting commotion combines mad funk horn riffs with virtuosic sax and trumpet soloing. Conclusive proof that if you push the boat out far enough, you get into very deep water.

12. ‘Who’ (David Byrne & St. Vincent) 2012 — idiosyncratic and stylish art-pop which veers into orchestral territory by blending saxophone funk riffs with beautifully played, warm-sounding French horn swells, courtesy of arranger Tony Finno.

13. ‘Flick Of The Finger’ (Beady Eye) 2013 — Liam Gallagher’s erstwhile rock outfit piles on the tension with a straightforward, steam-rollering brass arrangement featuring an epic, blasting theme, a regal high trumpet counterpoint and a nicely insinuating trombone semitone lick.

14. ‘My Sad Captains’ (Elbow) 2014 — mournful trumpets, largely voiced in thirds, enhance this song’s melancholy mood.

15. ‘Scream (Funk My Life Up)’ (Paolo Nutini) 2014 — a subtle, skillfully written brass arrangement with some deft rhythmic touches. After a quiet start, the horns come increasingly to the fore over the course of Nutini’s soulful ode to the doubtful charms of contemporary womanhood.

16. ‘Sue (Or In A Season of Crime)’ (David Bowie) 2014 — intriguing, left-field avant-garde jazz-pop with atonal tendencies, arranged by US composer/arranger/bandleader Maria Schneider. Lovely trombone chords at 3.56 and nice use of the Harmon mute on trumpet at 4.11, adding subtle, glinting notes in the background.

17. ‘Lingus’ (Snarky Puppy) 2014 — a live recording by this talented New York ensemble. A long-ish instrumental piece with a great, exuberant and catchy 5/4 horns lead line, in danger of being overshadowed by the blinding keyboard solo which follows.

18. ‘Roller Coaster’ (Dirty Loops) 2014 — the darling of musos the world over, this gifted Swedish trio wisely called in Jerry Hey (that name again) to arrange horns on their debut album Loopified. This harmonically mobile slice of fusion-funk-pop (for want of a better word) is given extra sheen by a brilliant Hey arrangement containing some frighteningly high trumpet notes. The track also features a jaw-dropping performance by bass phenomenon Henrik Linder.

19. ‘Got Me Runnin’ Round’ (Nickelback) (2014) — tasty, carefully placed brass riffs and swells intensify the feel of this funky offering by the Canadian rockers.

20. ‘How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful’ (Florence and the Machine) 2015 — a hypnotically repetitive, lyrical ballad which steadily builds to a climax with Will Gregory’s stately brass arrangement.

Instrumentation & Texture

Here are a few suggested instrumentation options for those using sampled pop horns. As mentioned in Part 1 of this series, a pairing of trumpet and tenor sax is very common, and it’s a good starting point for simple harmonies like those in diagrams 3 to 6. Trumpet takes the top line, tenor sax plays the lower part marked in red. If writing two-part harmonies in a higher register than these examples, you could substitute alto sax for tenor sax, or use two trumpets.

The closely voiced three-note chords in diagrams 7, 11, 12 and 14 sound fine with trumpet on top and two saxes underneath — again, depending on register, you might prefer to substitute alto for tenor sax, or go for the brighter sound of two high trumpets supported by a sax. However, the classic three-piece horn section sound of (from the top down) trumpet, tenor sax and trombone also sounds great for mid-range chords, particularly wider voicings such as those in diagram 8. Bear in mind that the trombone has a lower pitch range than tenor sax, so traditionally plays the lowest part.

For a regal, fanfare-like sound in the higher register (as in diagram 9), you can’t beat the sound of three trumpets, and if you want to maintain that pure, orchestral sound over a wider pitch register, add trombones for lower parts.

Different instrument combinations produce subtle variations of texture, so be prepared to experiment; there are no rules, and as a wise man once said, the only thing that matters is whether what you write sounds good!

Article Overview

Part 1: This new four-part series explains all you need to know about creating brass arrangements for a range of genres.

Part 2: The second in our four-part series deconstructs funk licks, discusses the implications of using live players and explains how to get more expression and feel into your sampled brass arrangements.

Part 3: A simple, catchy tune with a funky rhythm may be all you need to create a highly commercial horn hook — but harmony is also an essential ingredient in brass arrangements.

Part 4: We conclude our series with an overview of arrangement techniques and a peep into the world of big-band brass.