We conclude our series with an overview of arrangement techniques and a peep into the world of big-band brass.

For the purposes of study, most music can be broken down into three main elements: rhythm, melody and harmony. In this, the concluding article of the series, we’ll examine the role of each element and look at how they can be combined successfully in a horn arrangement. As outlined previously, rhythm is a vital component — the strong attack of the instruments lends itself well to emphatic articulation, resulting in the horns’ traditional role as purveyors of punchy interjections and rhythm licks. Syncopation and displacement play a big part, with notes and stabs often falling just before the beat. This has the effect of pushing the rhythm along, which is why musicians refer to anticipatory accents as ‘pushes’.

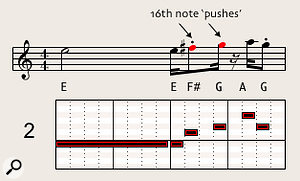

A simple example is the Chi-lites horn lick I mentioned last month. If written by an 18th-century composer such as Mozart, it might have been phrased as depicted in diagram 1 The Chi-lites horn lick from ‘Are You My Woman? (Tell Me So)’ as Mozart might have written it., ie. a straight, unsyncopated figure. Instead, the Chicago-based quartet play the lick as shown in diagram 2

The Chi-lites horn lick from ‘Are You My Woman? (Tell Me So)’ as Mozart might have written it., ie. a straight, unsyncopated figure. Instead, the Chicago-based quartet play the lick as shown in diagram 2 The real-life version of the Chi-lites horn lick, featuring a dancey, syncopated rhythm. Transcribed by Dave Stewart.: the third and fourth notes (marked in red) are shifted a 16th-note earlier, giving the phrase a restless, jumpy and danceable feel. The two red notes are known in the trade as ‘16th-note pushes’. Note also the staccato delivery, indicated by dots over notes — this is an essential part of soul and funk phrasing. By comparing the two versions, we can say with confidence that while Mozart was a pretty hot composer, he was absolutely rubbish at constructing 1970s funky soul licks.

The real-life version of the Chi-lites horn lick, featuring a dancey, syncopated rhythm. Transcribed by Dave Stewart.: the third and fourth notes (marked in red) are shifted a 16th-note earlier, giving the phrase a restless, jumpy and danceable feel. The two red notes are known in the trade as ‘16th-note pushes’. Note also the staccato delivery, indicated by dots over notes — this is an essential part of soul and funk phrasing. By comparing the two versions, we can say with confidence that while Mozart was a pretty hot composer, he was absolutely rubbish at constructing 1970s funky soul licks.

Syncopation & Pushes

When it comes to contemporary horn writing, few have attained the artistic heights reached by the maestro Jerry Hey. Two extracts from Hey’s arrangements demonstrate syncopation, pushes and off-beats combined to great effect: the first example is from Michael Jackson’s ‘Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough’ (from the 1979 album Off The Wall): the horn part shown in diagram 3  An extract from the horn part of Michael Jackson’s ‘Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough’, arranged by Jerry Hey.combines syncopated licks (in bars one, two and four) with the 16th-note pushed stab in bar three. This passage starts at 2m 57s, in the song’s third verse — the arrangement was performed by Hey’s legendary Seawind Horns, comprising two trumpets, trombone, tenor sax and baritone sax. In our extract, the trumpets play the top line, supported by (I think) tenor sax and trombone in the lower octave in the first two bars.

An extract from the horn part of Michael Jackson’s ‘Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough’, arranged by Jerry Hey.combines syncopated licks (in bars one, two and four) with the 16th-note pushed stab in bar three. This passage starts at 2m 57s, in the song’s third verse — the arrangement was performed by Hey’s legendary Seawind Horns, comprising two trumpets, trombone, tenor sax and baritone sax. In our extract, the trumpets play the top line, supported by (I think) tenor sax and trombone in the lower octave in the first two bars.

Jerry Hey went on to supply arrangements for Michael Jackson’s Thriller and Bad albums (both produced by Quincy Jones), which achieved astronomical sales figures. Hearing your horn arrangements blasting out on some of the biggest-selling albums of all time might be a cue for some to kick back and rest on their laurels but, 30 years on, Hey is still creating cutting-edge arrangements.

Our second extract is from Dirty Loops’ debut album Loopified, released last year. Diagram 4  The horn intro to Dirty Loops’ ‘Roller Coaster’, arranged by Jerry Hey.shows four bars of the intro of ‘Roller Coaster’ — this ferociously funky part is written along similar lines as the horn break in ‘Uptown Funk’ (notated in last month’s article), but it’s more intensely syncopated, crackles with rhythmic energy, and creates a fabulous interplay with the equally funky bass line. This is pop horn writing at its finest.

The horn intro to Dirty Loops’ ‘Roller Coaster’, arranged by Jerry Hey.shows four bars of the intro of ‘Roller Coaster’ — this ferociously funky part is written along similar lines as the horn break in ‘Uptown Funk’ (notated in last month’s article), but it’s more intensely syncopated, crackles with rhythmic energy, and creates a fabulous interplay with the equally funky bass line. This is pop horn writing at its finest.

The ‘Roller Coaster’ horn part starts with two on-beat staccato notes, followed by a four-note D-A-C-D phrase which repeats off the beat three eighth-notes later. (This type of displacement, which also occurs in the ‘Uptown Funk’ horn break, was discussed in part two of this series). Bar two features three consecutive 16th-note pushes on the note of A, resolving with a G-F-G-F-D descending blues lick. Although the original is played in the key of Eb-minor, I’ve notated it a semitone lower in our ‘home key’ of D-minor, in order to fit with the examples in earlier articles.

Off-beats & Rhythmic Counterpoint

Continuing our rhythmic dissertation, it’s not always necessary to use the kind of busy, complex syncopations featured in the last example. In his horn cover of ‘Somethinggood’ by Canadian electro-funk duo Chromeo, trumpet player and arranger Tom Walsh uses a simple rhythmic approach in the choruses, as shown in diagram 5 Tom Walsh’s horn cover of ‘Somethinggood’ punctuates the chorus vocal line with eighth-note horn off-beats. This extract is played in unison by four trumpets, tenor sax and trombone.. The repetitive vocal line (marked in blue) is punctuated by eighth-note horn off-beats, with a short fall (a descending pitch slide) added in the second and fourth bars. Tom’s highly effective arrangement (which covers a lot more musical ground than shown here) is scored for four trumpets, tenor sax and trombone — this extract is played in unison by the six instruments.

Tom Walsh’s horn cover of ‘Somethinggood’ punctuates the chorus vocal line with eighth-note horn off-beats. This extract is played in unison by four trumpets, tenor sax and trombone.. The repetitive vocal line (marked in blue) is punctuated by eighth-note horn off-beats, with a short fall (a descending pitch slide) added in the second and fourth bars. Tom’s highly effective arrangement (which covers a lot more musical ground than shown here) is scored for four trumpets, tenor sax and trombone — this extract is played in unison by the six instruments.

Having five or six horns at your disposal means you can indulge in a little rhythmic counterpoint. A good example occurs in Tower Of Power’s 1975 ‘Give Me The Proof’, where the interlocking horn rhythm depicted in diagram 6 repeats under the verse vocal. Note the 16th-note push played by the baritone sax in the second bar, which ends the phrase with a delightful staccato honk. A Hammond organ adds a great counter-rhythm to the mix, increasing the funk quotient to dangerous levels.

Unchained Melody

Interlocking horn rhythms from Tower Of Power’s 1975 ultra-funky ‘Give Me The Proof’, featuring fruity baritone sax interjections. Transcription from the www dot mindformusic dot com web site. Unless you’re writing a challenging instrumental piece, or a deliberately unhinged interlude like that heard on ‘Wild Women of Wongo’ by the Tubes (another Jerry Hey chart), horn melodies don’t have to be complicated. For pop/rock arrangements, short, simple and concise lines work best. You’ll recall that in the opening article of this series I mentioned the Manfred Mann Chapter Three song ‘One Way Glass’, sampled by the Prodigy and featured in the movie Kick-Ass — like the Chi-lites lick discussed earlier, the horn intro on that track is a simple melodic statement which owes its success to a great, catchy rhythm.

Interlocking horn rhythms from Tower Of Power’s 1975 ultra-funky ‘Give Me The Proof’, featuring fruity baritone sax interjections. Transcription from the www dot mindformusic dot com web site. Unless you’re writing a challenging instrumental piece, or a deliberately unhinged interlude like that heard on ‘Wild Women of Wongo’ by the Tubes (another Jerry Hey chart), horn melodies don’t have to be complicated. For pop/rock arrangements, short, simple and concise lines work best. You’ll recall that in the opening article of this series I mentioned the Manfred Mann Chapter Three song ‘One Way Glass’, sampled by the Prodigy and featured in the movie Kick-Ass — like the Chi-lites lick discussed earlier, the horn intro on that track is a simple melodic statement which owes its success to a great, catchy rhythm.

You don’t need a lot of notes to write a memorable tune: the horn hook in the Chairmen Of The Board’s ‘Give Me Just a Little More Time’ uses only three notes, while the sampled trumpet on Lunchmoney Lewis’ ‘Bills’ (currently riding high in the US singles chart) has only two! As long as you keep in mind the rhythmic devices discussed earlier, the notes themselves can be relatively simple. Two more Jerry Hey extracts illustrate this point: diagram 7 Jerry Hey’s majestic trumpet intro to Earth, Wind & Fire’s ‘In The Stone’ features simple, direct phrases. Transcription by Dave Stewart. shows Hey’s majestic intro to Earth, Wind & Fire’s ‘In the Stone’, which opens with a three-note trumpet figure over an orchestral strings backing. Admittedly, the trumpet line gets more complex as the intro progresses, but these simple and direct opening phrases immediately grab the attention.

Jerry Hey’s majestic trumpet intro to Earth, Wind & Fire’s ‘In The Stone’ features simple, direct phrases. Transcription by Dave Stewart. shows Hey’s majestic intro to Earth, Wind & Fire’s ‘In the Stone’, which opens with a three-note trumpet figure over an orchestral strings backing. Admittedly, the trumpet line gets more complex as the intro progresses, but these simple and direct opening phrases immediately grab the attention.

Many feel that Hey’s arrangements for jazzy soul singer Al Jarreau’s 1983 release Jarreau represent some of his best work. The intro to the album’s second track, ‘Boogie Down’, features a rousing intro played by trumpets and trombones in octaves over a dancey synth bass line. You can see it notated in  The intro to Al Jarreau’s ‘Boogie Down’ (arr. Jerry Hey), played by trumpets and trombones in octaves.diagram 8: the rhythm is a little tricky, but if you ignore the syncopation and slowly pick out the melody line in your own time, you’ll hear what a good tune it is.

The intro to Al Jarreau’s ‘Boogie Down’ (arr. Jerry Hey), played by trumpets and trombones in octaves.diagram 8: the rhythm is a little tricky, but if you ignore the syncopation and slowly pick out the melody line in your own time, you’ll hear what a good tune it is.

Harmonious Relations

When it comes to writing harmonies for your horn lines, you’ll find that most of the time a simple three-part harmony does the trick. If your arrangement uses minor-seventh or major-seventh chords, there’s no need to voice them as you would on a keyboard — you can leave the bass note (aka root) of the chord to the bass player, and have the horns play the upper three intervals (third, fifth and seventh), as shown in diagram 9. When played by horns, minor-seventh and major-seventh chords can be voiced with just three notes. Occasionally it’s nice to also omit the fifth (in this example, the note of A), leaving a plain two-note chord consisting of the third and seventh.

When played by horns, minor-seventh and major-seventh chords can be voiced with just three notes. Occasionally it’s nice to also omit the fifth (in this example, the note of A), leaving a plain two-note chord consisting of the third and seventh.

For simple chordal movements over a pedal bass note, you can use parallel voicings like those shown in the first bar of diagram 10. Parallel chordal movements over a pedal bass note (as shown in the first bar) work well. Alternatively, you can use a non-parallel movement like that in the second bar, which has a more serious ‘classical’ sound. Alternatively, you could use a non-parallel movement like that in the second bar, which has a more regal, somewhat ‘classical’ sound. Try playing both examples over a sustained bass note of D and you’ll hear what I mean! Departing from straight major and minor triads, I also recommend you experiment with the ‘sus 2’ chord introduced in last month’s article. Diagram 11

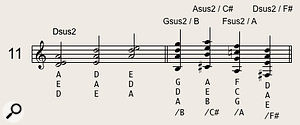

Parallel chordal movements over a pedal bass note (as shown in the first bar) work well. Alternatively, you can use a non-parallel movement like that in the second bar, which has a more serious ‘classical’ sound. Alternatively, you could use a non-parallel movement like that in the second bar, which has a more regal, somewhat ‘classical’ sound. Try playing both examples over a sustained bass note of D and you’ll hear what I mean! Departing from straight major and minor triads, I also recommend you experiment with the ‘sus 2’ chord introduced in last month’s article. Diagram 11 The three possible voicings of a Dsus2 chord. Playing the second D-A-E voicing over a bass note of F# creates an interesting chord that can be moved around through different keys to good effect, as shown in the second bar. shows the three possible voicings of a Dsus2; playing the second D-A-E voicing (a straight row of fourths) over an F# in the bass creates an interesting and distinctly non-jazzy chord. The second bar of diagram 11 shows this voicing moved around through different keys, which to my ears has a very nice effect — if you find it hard to play, record the first G-D-A / B chord into a sequencer then copy it into different positions!

The three possible voicings of a Dsus2 chord. Playing the second D-A-E voicing over a bass note of F# creates an interesting chord that can be moved around through different keys to good effect, as shown in the second bar. shows the three possible voicings of a Dsus2; playing the second D-A-E voicing (a straight row of fourths) over an F# in the bass creates an interesting and distinctly non-jazzy chord. The second bar of diagram 11 shows this voicing moved around through different keys, which to my ears has a very nice effect — if you find it hard to play, record the first G-D-A / B chord into a sequencer then copy it into different positions!

Diagram 12 The all-purpose, jazzy ‘7 flat 10’ (aka ‘7 sharp 9’) chord voicing, popularised by Jimi Hendrix in the sixties, has become a fixture in pop, rock and jazz. shows another good, all-purpose three-note chord — I call it a ‘7 flat 10’, but jazz musicians prefer ‘7 sharp 9’. Whatever one calls it, the chord distinguishes itself by containing both a major-third and a minor-third (the latter is placed up the octave, where it’s called a 10th). In horn arrangements of the seventies this voicing was often used for the dominant chord of a progression (in the key of D, that would be an A7b10 chord), but there’s no need to slavishly follow that convention — go ahead and play it in whatever key you like! This chord shape is easy to play on guitar, and its strained, yearning sound has become a fixture in pop, rock and jazz.

The all-purpose, jazzy ‘7 flat 10’ (aka ‘7 sharp 9’) chord voicing, popularised by Jimi Hendrix in the sixties, has become a fixture in pop, rock and jazz. shows another good, all-purpose three-note chord — I call it a ‘7 flat 10’, but jazz musicians prefer ‘7 sharp 9’. Whatever one calls it, the chord distinguishes itself by containing both a major-third and a minor-third (the latter is placed up the octave, where it’s called a 10th). In horn arrangements of the seventies this voicing was often used for the dominant chord of a progression (in the key of D, that would be an A7b10 chord), but there’s no need to slavishly follow that convention — go ahead and play it in whatever key you like! This chord shape is easy to play on guitar, and its strained, yearning sound has become a fixture in pop, rock and jazz.

As an alternative to the close-voiced block chords one usually hears in pop arrangements, it’s nice sometimes to open out the voicings and use wider intervals, as depicted in diagram 13. Chorale-style writing, featuring wider intervals and traditional classical harmony, works well in horn arrangements, particularly for slower, more reflective music. This chorale-style harmonised passage works well with an instrumentation of (from the top down) two trumpets, tenor sax and trombone.

Chorale-style writing, featuring wider intervals and traditional classical harmony, works well in horn arrangements, particularly for slower, more reflective music. This chorale-style harmonised passage works well with an instrumentation of (from the top down) two trumpets, tenor sax and trombone.

Elemental Brass

To summarise, the most effective horn arrangements combine strong rhythm, a good melody line and a cogent and pleasing sense of harmony. You can hear these elements at work in two extracts spanning a 36-year period: the first is Jerry Hey’s horn arrangement for rhythm and blues artist Bill Champlin’s ‘Yo Mama’, a track from the confusingly titled 1978 album Single. Diagram 14 Jerry Hey’s arrangement for Bill Champlin’s ‘Yo Mama’ combines the three elements required for a successful horn chart. shows an extract from the second chorus, scored for three trumpets (tenor sax and trombone play lower harmonies and octaves, not included in the diagram). The underlying chord sequence is E to A, two beats on each chord, with a change from D to A on the last two beats of the fourth bar.

Jerry Hey’s arrangement for Bill Champlin’s ‘Yo Mama’ combines the three elements required for a successful horn chart. shows an extract from the second chorus, scored for three trumpets (tenor sax and trombone play lower harmonies and octaves, not included in the diagram). The underlying chord sequence is E to A, two beats on each chord, with a change from D to A on the last two beats of the fourth bar.

Having announced their presence with a screaming, high-pitched fall on the downbeat, the horns sit on the rhythm with simple, close-voiced chords, throw in a cute little melodic lick in the second bar and end with a syncopated riff which culminates in a 16th-note pushed stab on a high-E. This four-bar passage is repeated (minus the opening fall) with an altered last bar featuring a wicked pair of 16th-note staccato pushed accents, notated in diagram 15. The last bar of the ‘Yo Mama’ chorus features a wicked pair of staccato 16th-note accents.

The last bar of the ‘Yo Mama’ chorus features a wicked pair of staccato 16th-note accents.

A more contemporary excerpt comes from an arrangement we introduced last month. Written by trumpet player Tom Walsh for three trumpets, tenor sax and trombone, it features three sustained horn chords which terminate with a 16th-note push in the third bar, leading to a pair of eighth-note accented chords and a final unison stabbed fall. This satisfying combination of rhythmic action, melody and harmony is notated in diagram 16. An extract from a contemporary arrangement by Tom Walsh, incorporating sustained chords and accented stabs.

An extract from a contemporary arrangement by Tom Walsh, incorporating sustained chords and accented stabs.

Structuring Your Arrangement

Once you’ve composed the basic building blocks of your arrangement, you face the task of deciding how to use them in the song. There’s more to this than meets than eye — Jerry Hey disciple Tom Walsh has this advice: “When studying any of Jerry’s classic arrangements, such as the Michael Jackson tracks ‘Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough’, ‘Workin’ Day And Night’ and ‘The Way You Make Me Feel’, it’s important to notice a couple of golden rules of his horn-arranging style:

1. The horns fill in the gaps, usually punctuating rhythmically in between vocal entries. If there are horns underneath a vocal, it’s usually long-note or pad-based material so as not to detract from the vocal line.

2. Know when to break out from unison (or unison octave) lines into voiced chords for maximum impact — a lot of Jerry’s ‘killer lines’ are played in unison, because the melody within them is so strong it doesn’t need harmonisation.

3. Know how to pace a horn chart — often first verses and choruses of songs sound better with no horns playing, so that when the horns come in later in the track, they’re noticeably adding something to the texture.

A good example of this last point is the Al Jarreau song ‘Save Me’ — the horns don’t even come in until three minutes into the track! Don’t be afraid to scrap lines you’ve written if they sound too dense within the music — when most writers start out (and I’m no exception!) they tend to over-write, but it’s important not to get too attached to lines you’ve written if they don’t work in the context of the music. Arranger Steve Sidwell, MD of The Voice UK series one and two and veteran of countless sessions, movie scores, commercials, TV shows and theatre productions, has this to say: “The most important factors in a brass arrangement are to understand the song, not get in the way of the vocals or other important lines, complement the rhythm section and try to create something that’s catchy in its own right. You have to be sensitive to the chord structure and the vocals in particular.”

The thoughts of these arrangers echo the sentiments of Wayne Jackson of the legendary Memphis Horns, who summed it up in five short words: “Don’t step on the singer.” To that, I’d add my own pithy epithet — if in doubt, leave it out.

Tom Walsh also ventured some thoughts on the subject of texture in horn arrangements: “Ninety percent of horn-section playing is done with an ‘open horn’ sound, but a Harmon mute on trumpet can add a nice buzz to certain lines (note the muted trumpets and vocal interlude on Al Jarreau’s ‘Love Is Real’). A classic sound for tracks with a lighter texture is to pair Harmon muted trumpet with flute (most professional sax players double on flute). Flute and flugelhorn (a valved brass instrument, similar in appearance to a trumpet but with a warmer, darker tone) also work very nicely — flugelhorn is a beautiful texture on softer R&B-style tunes, and sounds great when the horn section is playing at a more reserved dynamic.”

Big Band Theory

It was the English astronomer Fred Hoyle who said, “If you don’t go against the crowd, you’re not going to have any real successes.” Fred went against the crowd in a big way when he argued that the primaeval molecules from which life evolved on Earth had been transported from elsewhere in the universe, but it turned out he was right (probably). On a less cosmic level, arranger/bassist Laurence Cottle and drummer Gavin Harrison have also defied conventional wisdom by taking primaeval molecules of progressive rock riffs and fashioning them into entirely new, complex big-band arrangements, promoting the hypothesis that, as unlikely as it sounds, there may be intelligent musical life on Earth. The album in question, Cheating The Polygraph, features Cottle and Harrison’s imaginative fantasias on extracts of songs composed by the band Porcupine Tree, of which Harrison is a member.

A proper study of the 90-year history of big-band horn writing would require an exhaustive essay comprising many thousands of words, but a quick run-down of some of the musical highlights in Laurence Cottle’s Cheating The Polygraph scores should serve to give insights into this excellent present-day example of the genre. The album uses a standard big-band line-up of four trumpets, four trombones, five saxes, piano and rhythm section, augmented by tuba, euphonium, woodwinds, marimba and orchestral percussion. These additional instruments add a contemporary classical flavour to what would otherwise be a conventional big-band horn sound.

It always struck me that, in this musical style, the saxophones (technically reed instruments rather than brass) perform a role analogous to the strings in orchestral music; they weave a supple chordal tapestry and perform quicksilver darting melody lines, often harmonised, while the heavy brass (trumpets and trombones) interject stabs, accents and counter-melodies. The tonal contrast between the reeds and brass is often exploited by arrangers in ‘call and response’ phrases between the sections — when the two join together into a ‘shout chorus’ (a loud, climactic passage played by the entire band), it makes a very big sound indeed.

Big Is Beautiful

A common technique in big-band writing is the ‘thickened line’, in which a melody is beefed up by three or four parallel lower harmonies. Cheating The Polygraph contains many instances of this style, one example of which is notated in diagram 17. The ‘thickened line’ (a melody supported by three or four parallel lower harmonies) is a common big-band arrangement technique. This example (played by five saxophones) occurs in the track ‘The Sound Of Muzak’, from the album Cheating The Polygraph by Gavin Harrison and Laurence Cottle. Taken from the track ‘The Sound Of Muzak’, the extract features an alto sax melody line supported by (from the top down) a second alto sax, two tenor saxes and a baritone sax — a full saxophone quintet, played with enormous precision at frightening speed. This chordal melody is impossible to play on a keyboard at the written tempo, although the final Dm7-to-G7 movement in the last bar is just about manageable! The speed of the piece also makes it impossible to transcribe the parts by ear, so I was grateful to take a look at Laurence Cottle’s score. The arranger explained that the top line is a transcription of Steven Wilson’s guitar solo on the original Porcupine Tree recording of the song, slightly adapted to make it more saxophone-friendly.

The ‘thickened line’ (a melody supported by three or four parallel lower harmonies) is a common big-band arrangement technique. This example (played by five saxophones) occurs in the track ‘The Sound Of Muzak’, from the album Cheating The Polygraph by Gavin Harrison and Laurence Cottle. Taken from the track ‘The Sound Of Muzak’, the extract features an alto sax melody line supported by (from the top down) a second alto sax, two tenor saxes and a baritone sax — a full saxophone quintet, played with enormous precision at frightening speed. This chordal melody is impossible to play on a keyboard at the written tempo, although the final Dm7-to-G7 movement in the last bar is just about manageable! The speed of the piece also makes it impossible to transcribe the parts by ear, so I was grateful to take a look at Laurence Cottle’s score. The arranger explained that the top line is a transcription of Steven Wilson’s guitar solo on the original Porcupine Tree recording of the song, slightly adapted to make it more saxophone-friendly.

In his sleeve notes for the album, Gavin Harrison says, “To my ears, there’s something so appealing in hearing big fat chords played by brass players — the collective sound is so powerful and emotional, it resonates in a special way.” A nice application of this chordal approach occurs at 1m 45s in the track ‘Futile’, where Cottle assigns the seven pitches of a big chord to trombones and trumpets and staggers their entries over two bars, creating an effect not unlike pressing the sustain pedal of a piano and playing an arpeggio. You can see this notated in diagram 18. ‘Futile’ from Cheating The Polygraph features big seven-note horn chords played arpeggio-style, with instruments staggering their entries. This example shows a two-bar build into a chorus. This technique is used liberally throughout the album, reaching its zenith at 3m 42s in the composition ‘What Happens Now’, where rising arpeggios of a beautifully voiced pair of chords (Dmaj7/6/9/#11 to F#m11) are spread across four trombones and four trumpets.

‘Futile’ from Cheating The Polygraph features big seven-note horn chords played arpeggio-style, with instruments staggering their entries. This example shows a two-bar build into a chorus. This technique is used liberally throughout the album, reaching its zenith at 3m 42s in the composition ‘What Happens Now’, where rising arpeggios of a beautifully voiced pair of chords (Dmaj7/6/9/#11 to F#m11) are spread across four trombones and four trumpets.

Speaking of big chords, they don’t get much bigger than the massed aggregation of pitches that marks the end of ‘Start Of Something Beautiful’, continuing the time-honoured tradition of ending big-band tunes with a crazed, hysterical chord voicing, evoking feelings of alarm and terror in musicians and audiences alike. I’m rarely lost for words when it comes to naming chords, but I won’t even bother trying to think of a suitable moniker for this one — suffice it to say it contains every note of the A-major scale, played over a bass note of D (see diagram 19). The final chord of ‘Start Of Something Beautiful’ contains every note of the A-major scale spread across multiple octaves, played over a bass note of D. Nice!

The final chord of ‘Start Of Something Beautiful’ contains every note of the A-major scale spread across multiple octaves, played over a bass note of D. Nice!

These abbreviated score extracts barely scratch the surface of a brilliant set of arrangements bursting with ideas, and the tracks are recommended listening for all those interested in exploring the outer limits of contemporary big-band horn arranging.

Horn Part Notation

Should you find yourself in the position of being able to work with real horn players (and there are some very good, affordable ones out there), you’ll have to consider how to communicate what you want them to play. If you have no specific ideas but simply want to ‘hear some horns’, find a horn arranger and discuss your requirements with him or her. If you’ve already mocked up an arrangement but don’t know how to turn it into playable parts, consult the leader of the horn section, who will be pleased to help — these guys are very approachable and co-operative, and want you to get the best out of your track.

If you’re able to create your own arrangement and understand a little music theory, you can supply the players with parts yourself. A sensible way to go about it is to first create a score of all the instruments’ parts, written in concert pitch — that’s to say, what’s written on the score should correspond exactly to the real-life pitches of the horns. Once you’re happy with your score, you have to extract each part and (if necessary), transpose it for the instrument in question.

Transposition is one of music’s chores, akin to doing the washing-up or going to the dentist. Though the system was invented to make life easier for players, it makes things more difficult for the likes of you and me; basically, when generating parts for instruments such as trumpet in Bb and the saxophone family, you have to write them in a different pitch from the notes in your score. I won’t waste time explaining why, but like it or not, that’s the deal.

In the ‘Altered Key Signatures...’ box is a chart showing the transpositions required for trumpet in Bb (the standard model) and the saxophone family — one small mercy is that trombone is a non-transposing instrument! Although it’s not usually featured in big-band sections, I’ve included the soprano sax, the highest-pitched member of the saxophone family in common use; this has been a popular jazz soloing instrument since the 1930s, made famous by such stellar players as Sidney Bechet, John Coltrane, Wayne Shorter, Branford Marsalis and Jan Garbarek.

Although there is growing support for concert-pitch scores, most published works for orchestral and jazz works are transposed, and therefore hard for the layman to decipher. Since transposition only rears its head when engaging real players, I strongly suggest that you write out your scores in concert pitch — it makes it easy to see note relationships and work out your chord voicings, and helps keep you sane!

State Of Play

At the time of writing, few records in the UK and US singles charts feature full-scale brass arrangements, but real horns can still be heard amidst the synth-heavy productions. Solo trumpet is in fashion: the UK’s current chart-topper (a remix of OMI’s ‘Cheerleader’) features a trumpet hook played by Leonard Bywa, while Mark Crown adds an atmospheric trumpet line to the final bridge of Ed Sheeran & Rudimental’s ‘Bloodstream’. In a lighter vein (as mentioned earlier), Gamal ‘Lunchmoney’ Lewis’s enjoyable ‘Bills’ also sports an amusingly daft two-note trumpet break, which one heartless online reviewer describes as ‘relentlessly overzealous’. There’s just no pleasing some people

Horns adorn several other current chart singles — Meghan Trainor’s ‘Dear Future Husband’ is given extra welly by baritone and tenor saxes, Iggy Azalea’s ‘Trouble’ gets a massive soul injection from Jennifer Hudson’s rousing vocal and a classic (if somewhat subdued) horn arrangement, and a knockout combo of sampled bari sax riffs and real horn section counter-melodies helps to energise ‘Shake It Off’ by Taylor Swift. Trumping them all is Mark Ronson’s mega-hit ‘Uptown Funk’ (featuring Bruno Mars), which sends the funkometer soaring with its ‘70s-inspired horn break (explained in last month’s article), played by two trumpets, tenor sax, trombone and baritone sax.

Outside of the commercially pressurised, confected bubble of mainstream pop, many bands augment their line-up with a live horn section — the powerful, horn-driven sound of contemporary acts such as Sharon Jones & the Dap-Kings, Antibalas and the Budos Band (all from Brooklyn’s Daptone Records stable) keeps the soul flag flying, and accounts for the appearance of their musicians on the aforementioned ‘Uptown Funk’ and Amy Winehouse’s ‘Back To Black’.

While such soul and funk influences affirm the enduring appeal of genres forged in the creative fires of the mid-1960s, it seems unlikely that those styles will enjoy a mass revival any time soon; today’s music scene is more diverse, specialised and fragmented, which gives the opportunity for writers and arrangers to experiment with different approaches — for example, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t program four bars of big-band saxophones over a hip-hop track (and plenty of hip-hop producers do, though they tend to sample the horns from old records — definitely not recommended!), or write classical-sounding trumpet harmonies over an industrial hardcore track. Nowadays, anything goes — and if it sounds good, it is good.

As well as understanding the 20th-century heritage and musical principles of pop horns, would-be arrangers need to look to the future and not be unduly constrained by what went before. Thankfully, the work of arrangers and composers such as Jerry Hey, Greg Adams, Quincy Jones, Vince Mendoza, Django Bates, Maria Schneider, Michael League, Tom Walsh and Laurence Cottle shows that creativity will always shine through — it’s simply a question of trusting your imagination, exploring the musical possibilities and working hard to close the gap between what you hear in your head and what’s coming out of your speakers. Over to you!

Except where noted, Jerry Hey horn arrangement transcriptions are by Tom Walsh. Thanks to Tom Walsh, Steve Sidwell, Laurence Cottle and David Hearn.

Orchestral Avenues

In this series we’ve concentrated on pop (in the broad sense of the word) brass styles, deliberately turning a blind eye to the parallel universe of orchestral brass. That topic merits a series of its own, but there are areas where an orchestral instrumentation can spice up a pop arrangement. On Kanye West’s ‘All Of The Lights’ (featuring Rihanna and Kid Cudi), arranger Ken Lewis uses three trumpets, three French horns and two trombones to play a unison rhythmic figure that repeats throughout the song, adding melodic counterpoint and orchestral grandeur — you can hear this horns hook exposed in the breakdown at 4m 18s, revealing the simple harmonies played underneath the top line. As mentioned last month, another recent pop release featuring big, stately orchestral brass is Florence and the Machine’s sumptuous ‘How Big, How Blue, How Beautiful’.

Other instances of pop tracks with orchestral brass include the much-covered ‘Ready Or Not Here I Come’, originally recorded by the Delfonics in 1968. Thom Bell’s arrangement for this big production features a grandiose brass bass line under the staccato eighth-note strings figures in the intro, with heroic French horns, trumpets and trombones introduced later in the song. Forty years on, rapper T.I.’s ‘Live Your Life’ (featuring Rihanna) also bigs up the low end with a very effective sampled orchestral horns bass line.

Back To Mono: Brass Articulations

Brass instruments are essentially monophonic: although capable of weird ‘multiphonics’ effects, in which several notes are produced simultaneously, they’re basically designed to play one note at a time. If you find your sequenced brass lines sound unconvincing, it may be due to the fact that your MIDI notes are slightly overlapping, creating a temporary note-doubling effect which wouldn’t occur in a real instrument. You can eliminate this effect by setting your synth patch to monophonic mode. If you’re using a sampler, limit the polyphony to one voice — you can do this in Kontakt by reducing the maximum number of voices to ‘one’ on the front panel.

Orchestral sample-library users will be familiar with the concept of ‘interval legatos’ introduced by Vienna Symphonic Library (VSL) in 2002. This wonderful technique revolutionised the creation of smooth-sounding melody lines, greatly narrowing the gulf between instrument samples and the real thing. If you’re looking to program a lot of flowing melodies (such as the ‘thickened line’ big-band saxophones depicted in this article) in your horn arrangements, it would help to have a sound library with interval-legato capability: Fable Sounds’ Broadway Big Band has this feature, and I can recommend the VSL saxophone library as a good resource for linear writing and detailed programming. Sample Modeling’s modelled brass and wind solo instruments also produce amazingly smooth melody lines.

To program realistic big-band arrangements, you’ll need specialist articulations such as shakes, scoops, rips, falls and doits (as the onomatopoeic name suggests, the latter is a hysterical-sounding rising pitch appended to the end of a note). Chris Hein’s horns libraries include these articulations, as do the Fable Sounds and Sample Modeling instruments. To hear the styles in action, check out trumpet player Jon Harnum’s excellent online ‘Trumpet Sound Effects’ videos.

Altered Key Signatures For Transposed Parts

Key signatures are a handy way of globally indicating sharps and flats (also known as ‘accidentals’). When writing transposed parts for trumpet and saxes, you should also alter the song key signature in order to display the correct accidentals (this won’t affect how the music sounds, only how it looks on paper). Your DAW scoring page should include a menu of all the possible key signatures.

The table below  Transpositions required for trumpet and the saxophone family. Don’t worry about this unless you’re working with real players!shows the horns’ altered key signatures (marked in red) for all 12 keys — if your song is in G-major and you’re writing a trumpet or tenor sax part, select the key of A; for a baritone sax part, use the key of E. This also works for minor keys: an alto sax part for a song in the key of A-minor should be notated in the key of F#-minor. Being a non-transposing instrument, trombone is written in the original song key.

Transpositions required for trumpet and the saxophone family. Don’t worry about this unless you’re working with real players!shows the horns’ altered key signatures (marked in red) for all 12 keys — if your song is in G-major and you’re writing a trumpet or tenor sax part, select the key of A; for a baritone sax part, use the key of E. This also works for minor keys: an alto sax part for a song in the key of A-minor should be notated in the key of F#-minor. Being a non-transposing instrument, trombone is written in the original song key.

Song key Trumpet, Tenor Alto & & Soprano Sax Baritone Sax

C D A

C# (Db) D# (Eb) A# (Bb)

D E B

D# (Eb) F C

E F# (Gb) C# (Db)

F G D

F# (Gb) G# (Ab) D# (Eb)

G A E

G# (Ab) A# (Bb) F

A B F# (Gb)

A# (Bb) C G

B C# (Db) G# (Ab) There are two caveats: DAW scoring tools sometimes make a hash of transposed parts, displaying sharps and flats within the same bar, or even within the same chord. As a rule of thumb, you should avoid mixing them up. You can change an accidental in my DAW, Logic Pro, by highlighting a note or group of notes in the part, and going to Attributes / Accidentals and then selecting ‘Sharps To Flats’ or ‘Flats To Sharps’. If your song is atonal or has no fixed key signature, or you’re not sure which key signature is appropriate, leave it in the default key of C-major, which displays accidentals as and when they occur.

Article Overview

Part 1: This new four-part series explains all you need to know about creating brass arrangements for a range of genres.

Part 2: The second in our four-part series deconstructs funk licks, discusses the implications of using live players and explains how to get more expression and feel into your sampled brass arrangements.

Part 3: A simple, catchy tune with a funky rhythm may be all you need to create a highly commercial horn hook — but harmony is also an essential ingredient in brass arrangements.

Part 4: We conclude our series with an overview of arrangement techniques and a peep into the world of big-band brass.