The second in our four-part series deconstructs funk licks, discusses the implications of using live players and explains how to get more expression and feel into your sampled brass arrangements.

Last month (May 2015 issue) I traced the origins of modern pop (with a small ‘p’) brass arrangements back to the golden age of soul (1964-1970). Soul music lives on in contemporary R&B, notably in the vocal stylings and ballad writing; however, back in the late ‘60s it took a significant and exciting turn, mutating into the groove-based genre we call funk. Spearheaded by US artists such as Sly and the Family Stone and James Brown, funk became the hit sound of its day. Fun to play and great to dance to, the style continues to inspire today’s musicians, from the countless semi-pro bands playing funky covers to artists like Paulo Nutini and Mark Ronson, who utilise elements of ‘70s funk.

Funk was a watershed in popular music history. Before its arrival, most pop music was phrased in eighth notes over an up-tempo 4/4 beat. By slowing the tempo, funk created space for further rhythmic subdivision, so a bar of 4/4 could now accommodate 16 possible note placements. This opened up a new world of rhythm: with guitar and drums playing motoring, 16th-note-based patterns, other instruments were free to play in a more syncopated, broken-up style, which had a liberating effect on bass lines.

Woven together into a complex, contrapuntal musical tapestry, these interlocking parts produced a hypnotic ‘wheels within wheels’ effect, creating a revolutionary new, compelling and danceable feel. Looking back, some critics have complained that the emphasis on rhythm and attendant shift away from melody resulted in unmemorable songs, but at the time the majority of listeners were too busy ‘getting down with their bad selves’ (as one senior Tory politician put it) to worry about that.

Funk Rhythm Licks

Brass sections (aka horns) continued to play an important role throughout the funk era. In keeping with the general trend, their parts became more rhythmic and syncopated, and although song intros often featured a strong horns statement, the anthemic brass breaks of yesteryear were gradually phased out and replaced by guitar solos as the 1970s wore on. Nevertheless, the horns’ contribution remained vital. Our ‘20 Funk Tracks With Horns’ box shows a chronological listing of funk tracks featuring iconic brass arrangements, many of which still exert a strong influence on contemporary players and arrangers.

If you fancy adding some funky brass licks to your song, diagrams 1-5  Diagrams 1-5 show some typical rhythmic phrases that occur in funk horn arrangements, all notated in the key of D minor. For maximum funkiness, play them at a tempo of 104-106 bpm, using a strong solo trumpet or unison trumpet section sound.show some typical rhythmic phrases. For the sake of consistency, I’ve written them all in the key of D minor: they should be played emphatically at a tempo of around 104-106 bpm, using a strong solo trumpet or unison trumpet-section sound. (Remember that a dot written over the top of an eighth note indicates it should be played as a short staccato note.) These figures crop up repeatedly on funk tracks — you can use them as interjections to punctuate vocal lines, or as building blocks for an instrumental passage. The first three notes of diagram 4 can be used as a separate short phrase, and the last four notes of diagrams 4 and 5 will also work as standalone patterns.

Diagrams 1-5 show some typical rhythmic phrases that occur in funk horn arrangements, all notated in the key of D minor. For maximum funkiness, play them at a tempo of 104-106 bpm, using a strong solo trumpet or unison trumpet section sound.show some typical rhythmic phrases. For the sake of consistency, I’ve written them all in the key of D minor: they should be played emphatically at a tempo of around 104-106 bpm, using a strong solo trumpet or unison trumpet-section sound. (Remember that a dot written over the top of an eighth note indicates it should be played as a short staccato note.) These figures crop up repeatedly on funk tracks — you can use them as interjections to punctuate vocal lines, or as building blocks for an instrumental passage. The first three notes of diagram 4 can be used as a separate short phrase, and the last four notes of diagrams 4 and 5 will also work as standalone patterns.

Offbeat licks such as the phrase shown in diagram 6  Repeated offbeat licks were a common ’60s soul feature — the phrase shown here is a typical example.were a common ‘60s soul feature — Otis Redding’s ‘I Can’t Turn You Loose’ contains a classic example. Played at a hectic tempo, such phrases whizz by without causing too much disturbance, but when performed at the more relaxed pace of funk, their rhythmic detachment becomes more unsettling. Always keen on a spot of drama, James Brown exploited this mercilessly: without warning, the beat would suddenly stop and the whole band (including the bass) would hammer out a unison offbeat phrase like that in diagram 7,

Repeated offbeat licks were a common ’60s soul feature — the phrase shown here is a typical example.were a common ‘60s soul feature — Otis Redding’s ‘I Can’t Turn You Loose’ contains a classic example. Played at a hectic tempo, such phrases whizz by without causing too much disturbance, but when performed at the more relaxed pace of funk, their rhythmic detachment becomes more unsettling. Always keen on a spot of drama, James Brown exploited this mercilessly: without warning, the beat would suddenly stop and the whole band (including the bass) would hammer out a unison offbeat phrase like that in diagram 7, When played by the whole band at a slower tempo, offbeat phrases such as this become more rhythmically unsettling, especially when followed by a bar of silence! with a loud snare hit on each note. A bar of silence followed.

When played by the whole band at a slower tempo, offbeat phrases such as this become more rhythmically unsettling, especially when followed by a bar of silence! with a loud snare hit on each note. A bar of silence followed.

This subversive combination of quirky rhythm and empty space left listeners hanging in mid-air — one shudders to think of its effect on the profoundly arrhythmic British TV studio audiences of the day, whose idea of ‘getting on down’ (with or without their bad selves) consisted of lamely clapping along on the downbeat. Mr. Brown’s hip rhythmic trick poses a challenge: how do you feel the underlying beat when it’s not there? See the box ‘Get On The Good Foot’ for a suggested solution.

Another common device in funk is rhythmic displacement — a short phrase is played on the downbeat and then repeated three eighth-notes later, causing the reiteration to start on the offbeat. A simple example is the bass riff in diagram 8 Rhythmic displacement is created by repeating a short phrase three eighth-notes later — this simple bass riff uses the technique to great, tension-building effect., a devilishly effective, tension-building lick, which sounds great played by unison Rhodes and bass over a straight funk drum beat. Applying the same idea to melody lines gives rise to phrases like the pair shown in

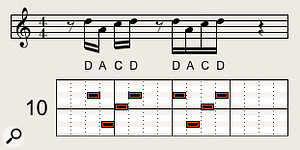

Rhythmic displacement is created by repeating a short phrase three eighth-notes later — this simple bass riff uses the technique to great, tension-building effect., a devilishly effective, tension-building lick, which sounds great played by unison Rhodes and bass over a straight funk drum beat. Applying the same idea to melody lines gives rise to phrases like the pair shown in Applying rhythmic displacement to melody lines gives rise to phrases like the pair shown here: each phrase starts on the downbeat, then repeats on the offbeat between the second and third beats of the bar. diagram 9: each lick starts out on the downbeat, then repeats on the offbeat between the second and third beats of the bar. The technique works the other way round: begin the phrase on an offbeat (as in diagram 10) and the reiteration starts on the beat (in this case, beat 3 of the bar).

Applying rhythmic displacement to melody lines gives rise to phrases like the pair shown here: each phrase starts on the downbeat, then repeats on the offbeat between the second and third beats of the bar. diagram 9: each lick starts out on the downbeat, then repeats on the offbeat between the second and third beats of the bar. The technique works the other way round: begin the phrase on an offbeat (as in diagram 10) and the reiteration starts on the beat (in this case, beat 3 of the bar).

Live Brass Arrangements

If you begin a phrase on the offbeat, its rhythmically displaced reiteration starts on the beat (in this case, beat 3 of the 4/4 bar).Adding brass arrangements to your live band’s set can be an exciting experience: bringing in one, two or three horn players (provided they can play in tune and in time!) will liven things up and add a new sonic dimension. With that in mind, common line-ups are listed in the ‘Horn Section Instrumentation’ box. However, if no live players are available, there are other solutions: keyboardists can perform horn parts on their instruments, and the miniaturisation of modern workstations and MIDI controller keyboards makes it feasible for another band member to whip out brass parts while the main keyboard player takes care of the traditional Rhodes/Clavinet/Hammond comping duties.

If you begin a phrase on the offbeat, its rhythmically displaced reiteration starts on the beat (in this case, beat 3 of the 4/4 bar).Adding brass arrangements to your live band’s set can be an exciting experience: bringing in one, two or three horn players (provided they can play in tune and in time!) will liven things up and add a new sonic dimension. With that in mind, common line-ups are listed in the ‘Horn Section Instrumentation’ box. However, if no live players are available, there are other solutions: keyboardists can perform horn parts on their instruments, and the miniaturisation of modern workstations and MIDI controller keyboards makes it feasible for another band member to whip out brass parts while the main keyboard player takes care of the traditional Rhodes/Clavinet/Hammond comping duties.

The caveat here is that, as explained in last month’s article, keyboard brass patches and/or samples need to sound strong and reasonably authentic. Avoid orchestral brass, and don’t choose a patch merely because it has ‘horns’ in its title. Instead, listen carefully to all the options, and pick presets that have the punch and attitude of real brass instruments. A little judicious patch editing can make a big difference: turning off reverb and delay effects, removing filter resonance and setting attack envelopes as fast as possible all help give a sound maximum bite and fatness.

Whether you’re working with live horn players or a keyboard facsimile, the important thing is to aim for a properly integrated arrangement. This means that, rather than simply pasting a brass overlay on your band’s habitual rendition of a tune, the musicians should listen carefully to the horn arrangement and consider how they might adapt their part to accommodate it.

Synchronise Yourselves

I’ll give you some examples: when the horns are playing chord pads (an area I’ll explore in next month’s article), the keyboard player and guitarist should make sure the chord voicings they’re using blend harmoniously with the horn parts. This is more subtle than it sounds — musicians have idiosyncratic ideas on how to voice chords, and a shape called ‘G7/9’ can be played in many different ways. Ideally, the keyboardist and guitarist would play along with a MIDI mock-up of the brass arrangement, listening out for any clashes or awkward moments: it may be a question of making a chord less dense, changing or omitting its top note or shifting it into a different register, but efforts should be made to find the optimum chordal blend across all the players. This kind of work is best done without drums at a moderate volume, rather than with the whole band hammering out the song at cranked-up performance levels.

In the same way, rhythm patterns also need to be synchronised. If the horns were playing the lick in the second bar of diagram 9, it would help if the guitarist adapted his or her rhythm playing to the same kind of 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2 phrasing (as shown in diagram 11) When working with live horn players, guitarists can adapt their rhythm playing to fit the horns’ phrasing. This example shows a guitar rhythm that fits nicely with the horns phrase in the second bar of diagram 9; both patterns utilise a 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2 phrasing, resulting in a strong, interlocking composite rhythm part. , rather than strumming on regardless in a foursquare fashion. With horns and guitar playing a strong interlocking rhythm, keyboards don’t need to compete: rather than overloading the rhythm with a busy Clavinet part à la Stevie Wonder’s ‘Superstition’ (which I read, incidentally, is actually a composite of several overdubs), a few cool, well-placed Rhodes stabs would do. Overplaying is a common fault in semi-pro bands, and piano-trained keyboard players are often guilty of overdoing the left-hand action — leave it to the bass player, guys!

When working with live horn players, guitarists can adapt their rhythm playing to fit the horns’ phrasing. This example shows a guitar rhythm that fits nicely with the horns phrase in the second bar of diagram 9; both patterns utilise a 1-2-3, 1-2-3, 1-2 phrasing, resulting in a strong, interlocking composite rhythm part. , rather than strumming on regardless in a foursquare fashion. With horns and guitar playing a strong interlocking rhythm, keyboards don’t need to compete: rather than overloading the rhythm with a busy Clavinet part à la Stevie Wonder’s ‘Superstition’ (which I read, incidentally, is actually a composite of several overdubs), a few cool, well-placed Rhodes stabs would do. Overplaying is a common fault in semi-pro bands, and piano-trained keyboard players are often guilty of overdoing the left-hand action — leave it to the bass player, guys!

It goes without saying (but I’ll say it anyway) that unison accents like those shown in diagram 7 should be tightly played by the whole band with no embellishments, and if a passage culminates in a big, dramatic chord like the one shown in diagram 12 Big, accented, dramatic, off-the-beat horn chords like this one need to be played cleanly by the whole band. Woe betide anyone (except the drummer) who fails to leave a rest on the preceding downbeat!, it’s vital that everyone leaves a rest at the top of the bar and hits the chord cleanly on the second beat. (The exception would be the drummer, who can play a single kick-drum note on the downbeat.) God help any member of James Brown’s band who screwed up such a musical moment — renowned for his volatile and explosive temper, the aptly nicknamed Mr Dynamite was notoriously intolerant of any slight deviation from the chart. One fears for the life of the hapless horn player who plays an obvious wrong note during an exposed, ascending staccato phrase in Brown’s song ‘Cold Sweat’; I just hope the guy had life insurance.

Big, accented, dramatic, off-the-beat horn chords like this one need to be played cleanly by the whole band. Woe betide anyone (except the drummer) who fails to leave a rest on the preceding downbeat!, it’s vital that everyone leaves a rest at the top of the bar and hits the chord cleanly on the second beat. (The exception would be the drummer, who can play a single kick-drum note on the downbeat.) God help any member of James Brown’s band who screwed up such a musical moment — renowned for his volatile and explosive temper, the aptly nicknamed Mr Dynamite was notoriously intolerant of any slight deviation from the chart. One fears for the life of the hapless horn player who plays an obvious wrong note during an exposed, ascending staccato phrase in Brown’s song ‘Cold Sweat’; I just hope the guy had life insurance.

Hopefully, the MD of your rocking combo is of a less murderous disposition, but in any case, the horn players themselves should be able to offer guidance on integrating their instruments with the rest of the band. If written charts are required, unless you know what you’re doing, speak to the horn players before blithely entrusting the job to your DAW’s scoring tools: there are issues regarding transposition which need to be addressed, but I won’t go into that at this point for fear of putting you off! Suffice it to say that a chat with the musicians concerned before starting rehearsals should straighten out any technical or notation problems, and the horn players are likely to have creative ideas of their own about the arrangement’s musical details.

A Wondrous Thing

Funk horn parts need a strong melody as well as a hip rhythm. An example of a horns lick that combines both occurs in the Stevie Wonder track ‘You Haven’t Done Nothin’’, one of the entries in our ‘20 Funk Tracks With Horns’ box. This song is like the evil twin of ‘Superstition’, featuring a slower tempo, a heavier Clavinet part and a booming kick drum on the first and third beats of the bar — it also features the Jackson 5 on backing vocals, a poignant reminder that Jackson number five (who cited James Brown as his biggest influence) is no longer with us. If all that isn’t enough, the song’s lyrics take a well-aimed swipe at President Richard Nixon.

An extract from the horns part played in the chorus of Stevie Wonder’s 1974 single ‘You Haven’t Done Nothin’’, transcribed by Dave Stewart. The notes of the opening phrase repeat in a slightly different rhythmic form in the second bar, creating a very catchy melody line. In order to match the tonality of other musical examples in this article, this extract is transposed down a semitone from the original key of Eb.The chorus of ‘You Haven’t Done Nothin’’ features the two-bar horn phrase shown in diagram 13. Why is this horn line so cool? I’d say it’s mainly due to the rhythmic twist in its second half: having started out as a straight downbeat tune, the phrase’s rhythm is tweaked in the second bar so that the top note of C shifts back onto the offbeat, after which it’s reiterated as a pair of quick 16th notes before moving down to B. Little pitch-bends and falls also help give the riff its character — though its musical effect is simple, it’s actually a gem of brass writing.

An extract from the horns part played in the chorus of Stevie Wonder’s 1974 single ‘You Haven’t Done Nothin’’, transcribed by Dave Stewart. The notes of the opening phrase repeat in a slightly different rhythmic form in the second bar, creating a very catchy melody line. In order to match the tonality of other musical examples in this article, this extract is transposed down a semitone from the original key of Eb.The chorus of ‘You Haven’t Done Nothin’’ features the two-bar horn phrase shown in diagram 13. Why is this horn line so cool? I’d say it’s mainly due to the rhythmic twist in its second half: having started out as a straight downbeat tune, the phrase’s rhythm is tweaked in the second bar so that the top note of C shifts back onto the offbeat, after which it’s reiterated as a pair of quick 16th notes before moving down to B. Little pitch-bends and falls also help give the riff its character — though its musical effect is simple, it’s actually a gem of brass writing.

Satisfyingly, the single reached number one in the US pop and soul charts in November 1974, and Nixon resigned two days after it was released: proof that no matter how powerful, tricky and lawyered-up you are, you can’t fight the funk!

Keyswitches, Phrasing & Dynamics

Readers who use sample libraries (especially the orchestral kind) will be familiar with ‘keyswitches’: specially designated, non-sounding keys used to select an instrument’s different playing styles. Most sample-library manufacturers provide keyswitchable presets; the keyswitch notes are usually positioned below the playing range of the instrument, so you can play a tune with your right hand and change articulations on the fly with your left — press a low C to select sustains, and C# for staccato, for example. It takes practice and a modicum of two-handed dexterity to perform keyswitching in real time, but you can always insert the keyswitch MIDI notes in your DAW’s sequencer after the event.

The library I used when writing the musical examples for this article (Chris Hein Horns Vol. 2) makes extensive use of keyswitches. Its ‘Solo Trumpet A’ patch contains 18 different articulations, enabling users to add expressive gestures such as a crescendo, a grace note, a fall (a quick descending pitch slide) or a ‘doit’ (a short accented note terminating in an exaggerated upward glissando slur — a popular effect with jazz big-band arrangers). When playing the aforementioned Stevie Wonder horns lick into my sequencer, I keyswitched to a fall sample for the last note of the first phrase, which sounded more realistic than using the pitch wheel.

The keyboard layout used in the Chris Hein Horns Vol. 2 sample library. Keyswitches (marked in yellow) access 18 different playing styles, while the instrument’s playable samples (shown in traditional black and white) are mapped at the upper end of the keyboard. The red ‘hot keys’ reiterate the last note you played with an articulation of your choice, enabling you to instantly trigger (for example) a fall without having to play a separate right-hand note.Although such techniques can be a great aid to realism, traditional musical factors like note duration and dynamics can have just as much bearing on the success (or otherwise) of a phrase. The first four notes of the Stevie Wonder horn part need to be played long-short-long-short, with a slight emphasis on the long notes; if you play all the notes with the same duration and dynamic, the feel goes out of the window. Subtle timing variations also have a big impact on feel, so if something isn’t sounding right, think about the details of how you’re playing it, rather than immediately reaching for a quick-fix technical solution!

The keyboard layout used in the Chris Hein Horns Vol. 2 sample library. Keyswitches (marked in yellow) access 18 different playing styles, while the instrument’s playable samples (shown in traditional black and white) are mapped at the upper end of the keyboard. The red ‘hot keys’ reiterate the last note you played with an articulation of your choice, enabling you to instantly trigger (for example) a fall without having to play a separate right-hand note.Although such techniques can be a great aid to realism, traditional musical factors like note duration and dynamics can have just as much bearing on the success (or otherwise) of a phrase. The first four notes of the Stevie Wonder horn part need to be played long-short-long-short, with a slight emphasis on the long notes; if you play all the notes with the same duration and dynamic, the feel goes out of the window. Subtle timing variations also have a big impact on feel, so if something isn’t sounding right, think about the details of how you’re playing it, rather than immediately reaching for a quick-fix technical solution!

The Real Lowdown

Last month we looked at creating a brass arrangement for two instruments, starting with a trumpet top line and doubling the part with tenor sax an octave lower. We can expand the section further by adding a trombone (which can play lower parts than the tenor), and if we want to put together a full horn section, we can also include an alto sax (or a second tenor sax) and baritone sax. These instruments’ playing ranges are shown in the ‘Instrument Ranges’ box.

The bari sax (as musos call it) is versatile. The lowest-pitched member of the saxophone family in everyday use, it plays the low parts in sax quartets, and has a proud history in blues and jazz as a fluent, expressive improvising solo instrument. It also performs an important role in soul and funk horn arrangements, honking out beefy staccato bass lines and the occasional blasting solo. (Check out the great bari sax rhythm part in Tower of Power’s ‘Diggin’ On James Brown’.) In the parallel universe of late-20th-century pop, Yello’s ‘The Race’ and D:Ream’s ‘Things Can Only Get Better’ (the latter featuring a starry-eyed Professor Brian Cox on keyboards!) used raspy sampled bari sax riffs to create rhythmic momentum.

These archetypal baritone sax phrases are a quick and enjoyable way of adding instant period colour to an arrangement: the first is a simple semitone lead-in to the root of a chord, while the second bar shows the classic ‘semitone wiggle’ soul lick.If you’re looking for some simple and effective retro-flavoured baritone sax phrases, they don’t get much simpler than the funk/soul lick shown in the first bar of diagram 15, which consists of just two notes (a semitone lead-in to the root of a chord). Alternatively, the instrument sounds very fruity playing the lewd ‘semitone wiggle’ soul lick illustrated in the second bar. These archetypal phrases are a quick and enjoyable way of adding instant period colour to an arrangement.

These archetypal baritone sax phrases are a quick and enjoyable way of adding instant period colour to an arrangement: the first is a simple semitone lead-in to the root of a chord, while the second bar shows the classic ‘semitone wiggle’ soul lick.If you’re looking for some simple and effective retro-flavoured baritone sax phrases, they don’t get much simpler than the funk/soul lick shown in the first bar of diagram 15, which consists of just two notes (a semitone lead-in to the root of a chord). Alternatively, the instrument sounds very fruity playing the lewd ‘semitone wiggle’ soul lick illustrated in the second bar. These archetypal phrases are a quick and enjoyable way of adding instant period colour to an arrangement.

Big Brass Chords

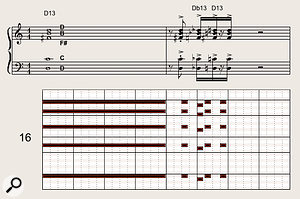

A typical jazzy voicing for a five-horn line-up — from the top, trumpet, alto sax, tenor sax, trombone and baritone sax combine to play a familiar 13th chord. Such chords can be animated by adding rhythmic and melodic movement, as shown in the second bar.Though beyond the requirements of most pop/rock bands, a five-horn line-up is great for constructing big chords. Diagram 16 shows a typical jazzy voicing: working from the top down, the high trumpet note (D) is harmonised with a B and F# (played by two saxes). Played on its own, this triad would constitute a B-minor triad, but adding a lower C (played by trombone) transforms the chord into something more mysterious and rootless. Giving the baritone sax a low-D bass note fixes the tonality as a familiar jazz 13th chord. However, if you played a G# or A in the bass instead, it would be a different story! Regardless of harmonic content, the sound of five horn players playing a composite chord is very powerful, especially when some funky rhythmic and melodic movement is introduced (as in the second bar of diagram 13).

A typical jazzy voicing for a five-horn line-up — from the top, trumpet, alto sax, tenor sax, trombone and baritone sax combine to play a familiar 13th chord. Such chords can be animated by adding rhythmic and melodic movement, as shown in the second bar.Though beyond the requirements of most pop/rock bands, a five-horn line-up is great for constructing big chords. Diagram 16 shows a typical jazzy voicing: working from the top down, the high trumpet note (D) is harmonised with a B and F# (played by two saxes). Played on its own, this triad would constitute a B-minor triad, but adding a lower C (played by trombone) transforms the chord into something more mysterious and rootless. Giving the baritone sax a low-D bass note fixes the tonality as a familiar jazz 13th chord. However, if you played a G# or A in the bass instead, it would be a different story! Regardless of harmonic content, the sound of five horn players playing a composite chord is very powerful, especially when some funky rhythmic and melodic movement is introduced (as in the second bar of diagram 13).

I understand that creating big jazzy chords may not be a priority for all SOS readers, but I mention them in this context because they crop up in some outstanding funk horn arrangements. Personally, I’m not a great fan of the old school, jazz-centric method of chord construction, where a succession of major or minor third intervals are piled over a root note — the resulting ‘balancing donuts’ shapes sound pretty tired. Happily, there are plenty of ways of creating big horn section chords without resorting to jazz clichés, and I’ll talk about that in a forthcoming article.

Next Up

I realise this is a big subject, and that I’m only scratching the surface of some musical areas — people far more learned than myself have written books on brass arranging which go a lot deeper. Nevertheless, I hope some of this is helpful, and that those of you who can’t read music will be able to figure out some of the examples (in particular, their rhythms) via the piano-roll graphics. I’ll be back here in precisely 30 days time expounding on harmony, texture and counterpoint in brass arrangements, so be sure to set your watches.

20 Funk Tracks With Horns

The late 1960s saw the rise of funk as a worldwide musical force, with brass sections playing a major part on many recordings. Here are 20 funk tracks with prominent horn arrangements, listed in chronological order — apologies if I omitted your favourite record or artist! To illustrate the origins and development of the genre, this selection focuses on the ’70s, but the final listing represents the current state of the art: performed by Dirty Loops, this contemporary track features a horn arrangement by the great Jerry Hey of Seawind Horns and Michael Jackson fame. Mr Hey and co.’s contribution (which enters at the midway point) is somewhat buried in the mix, but a horns-heavy instrumental excerpt with top-line notation has been posted online.

- ‘Cold Sweat’ (James Brown & the Famous Flames), 1967.

- ‘It’s My Thing (You Can’t Tell Me Who To Sock It To)’ (Marva Whitney), 1969.

- ‘Listen To Me’ (Baby Huey), 1971.

- ‘(I Got) So Much Trouble in My Mind’ (Joe Quarterman & Free Soul), 1972.

- ‘Superstition’ (Stevie Wonder), 1972.

- ‘Fencewalk’ (Mandrill), 1973.

- ‘What Is Hip’ (Tower of Power), 1973.

- ‘Soul Vaccination’ (Tower Of Power), 1973.

- ‘Pick Up the Pieces’ (Average White Band), 1974.

- ‘You Haven’t Done Nothin’’ (Stevie Wonder), 1974.

- ‘Hair’ (Graham Central Station), 1974.

- ‘Stomp and Buck Dance’ (The Crusaders), 1974.

- ‘Maybe It’ll Rub Off’ (Tower Of Power), 1975.

- ‘Give Me the Proof’ (Tower Of Power), 1975.

- ‘I Wish’ (Stevie Wonder), 1976.

- ‘Too Hot To Stop’ (The Bar-Kays), 1976.

- ‘Jupiter’ (Earth, Wind & Fire), 1977.

- ‘Serpentine Fire’ (Earth, Wind & Fire), 1977.

- ‘You Are A Winner’ (Earth, Wind & Fire), 1981.

- ‘Lost In You’ (Dirty Loops), 2014.

You can probably identify the sole UK act in this list by its self-deprecating name!

Horn Section Instrumentation

Tom Walsh horn section.Photo: Tom WalshAdding a single live horn player to your band line-up will make an immediate musical and visual impression. The most common solo instrument is saxophone (usually tenor sax), followed by trumpet. Solo trombone is fairly unusual — to hear its effect, listen to Groove Armada’s ‘At the River’.

Tom Walsh horn section.Photo: Tom WalshAdding a single live horn player to your band line-up will make an immediate musical and visual impression. The most common solo instrument is saxophone (usually tenor sax), followed by trumpet. Solo trombone is fairly unusual — to hear its effect, listen to Groove Armada’s ‘At the River’.

Assuming players are of a decent standard, two horns is better than one (as proved beyond doubt by the Memphis Horns), and three opens up a world of harmony. In contrast to the somewhat rigid instrumentation of classical music, there are no hard and fast rules about which instruments can play together — in the more flexible pop, rock and jazz scenes, such choices tend to be determined by musicians’ availability rather than the wishes of an MD or composer.

Some of the more common instrumental combinations are shown below: a single saxophone within an ensemble often defaults to the tenor instrument, but depending on the musical style, a line-up containing two saxophones could feature both alto and tenor saxes. To mock up a full brass arrangement using samples, the instruments you’ll need are trumpet, tenor sax, trombone, alto sax and baritone sax, but you can omit the last two for simpler band arrangements.

Two players:

- Trumpet and tenor sax.

- Trumpet and trombone.

- Two saxes.

- Sax and trombone (a rare combination, check out the Jazz Crusaders’ ‘Sting Ray’).

Three players:

- Trumpet, sax and trombone.

- Trumpet and two saxes.

- Two trumpets and sax.

Four players:

- Two trumpets, sax and trombone.

- Trumpet, two saxes and trombone.

Five players:

- Trumpet, two saxes, trombone and baritone sax.

- Two trumpets, two saxes and baritone sax.

Six players:

- Two trumpets, two saxes, trombone and baritone sax.

Get On The Good Foot

Diagrams 17-20 show some typical funk syncopated rhythm patterns. To develop your ability to feel the underlying beat while playing such syncopations, try the techniques suggested in the ‘Get On The Good Foot’ box.Any musician interested in playing funk needs to have a grasp of its rhythmic vocabulary: that means not only an academic understanding of the various common syncopations (some of which are quite tricky), but also the ability to feel the underlying beat while playing them.

Diagrams 17-20 show some typical funk syncopated rhythm patterns. To develop your ability to feel the underlying beat while playing such syncopations, try the techniques suggested in the ‘Get On The Good Foot’ box.Any musician interested in playing funk needs to have a grasp of its rhythmic vocabulary: that means not only an academic understanding of the various common syncopations (some of which are quite tricky), but also the ability to feel the underlying beat while playing them.

Funk music’s enduring legacy is its use of 16th-note subdivisions. The best way of getting to grips with these small rhythmic units is to set a quarter note (four beats per bar) metronome running in your sequencer, slow the tempo down to 50-60 bpm and count out 1-2-3-4 evenly over each metronome tick, representing the four 16th-note subdivisions embedded in every beat of a 4/4 bar. It helps to tap your foot on the ‘one’ while using a hand to tap out the 16s. (Don’t do this too vigorously, or the neighbours will start banging on the wall.)

Some typical funk syncopated patterns are shown in diagrams 17-20. Try tapping out these rhythms slowly and repeatedly, keeping your foot going on the ‘one’ — after a while, you’ll begin to physically feel how the syncopation works over the 4/4 beat. After that you can gradually increase the tempo and work up to playing the rhythm at a realistic song speed (say 100-110 bpm). Of these four examples, the hardest to feel is the last one — since it’s a rhythmic phrase that crops up in countless funk-track horn arrangements, it’s advisable to get this one under your belt.

Although this slow, repetitive rehearsal procedure seems unrewarding at the time, it’s the only way to build a solid rhythmic feel. The important thing is to maintain a steady rhythm with a strong downbeat in your foot and a nice, even ‘1-2-3-4’ pulse in the hand. With enough practice, you’ll be able to stop tapping and actually sense the beat in your head (a kind of mental metronome), giving you the security to accurately perform syncopated phrases without losing the beat.

Instrument Ranges

The diagram above shows the playing ranges of trumpet in Bb, trombone and the three principal members of the saxophone family (alto, tenor and baritone). Middle C (marked in blue) is C4.As mentioned last month, although good players can produce notes above and below these ranges, it’s advisable to keep parts within comfortable limits to avoid the sound of the instrument becoming thin, strained and unmusical.

Article Overview

Part 1: This new four-part series explains all you need to know about creating brass arrangements for a range of genres.

Part 2: The second in our four-part series deconstructs funk licks, discusses the implications of using live players and explains how to get more expression and feel into your sampled brass arrangements.

Part 3: A simple, catchy tune with a funky rhythm may be all you need to create a highly commercial horn hook — but harmony is also an essential ingredient in brass arrangements.

Part 4: We conclude our series with an overview of arrangement techniques and a peep into the world of big-band brass.