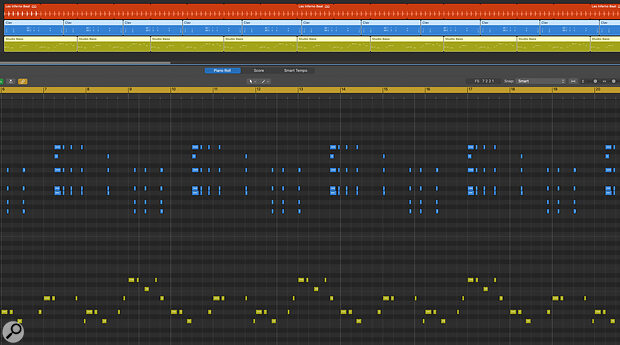

Screen 1: Convert loops of differing lengths to real copies to extract the best parts.

Screen 1: Convert loops of differing lengths to real copies to extract the best parts.

If your beats are static, your melodies predictable, or if you’re just plain out of ideas, perhaps it’s time to introduce some random elements?

Aleatoric music is a composition technique incorporating some degree of ‘chance’. Some elements are left to the performer’s discretion, so there is a degree of random probability when and if some elements in the music will occur. Aleatoric techniques can be used to introduce variation and interest to an existing composition, to inspire new ideas or to create a wholly ‘generative’ piece of music. Modern DAWs and plug‑ins can introduce these deterministic elements into our music production. Here we’ll look at a few techniques available in most modern DAWs and many plug‑ins.

Loop‑De‑Loop

One simple way of introducing evolving interactions between parts is to loop regions (aka clips or events) of different lengths. Because of the offset timing, each iteration yields slightly different results when played back together. Too much indeterminacy, however, can lead to chaos. To get useful and interesting results, couple this with some regular recurring parts that anchor the music. For example, set up a regular recurring ostinato in one or more parts alongside the evolving loops.

This technique works great for film score‑style musical development. The permutations generated by the repeating loops, coupled with a steady pulse, create variety while maintaining thematic consistency.

The same idea works well with groove‑based music with either a static, or simple, harmonic progression. Set the loops to beat‑based offsets to create interesting syncopations. In the example in Screen 1 (above), I place a four‑bar (green) bass part alongside a (blue) clav part that is three bars and one beat long. When both are looped, the offsets generate some interesting (and some not so interesting) rhythmic interactions. To take control of the evolving parts, convert the loops to real copies, then choose the best bits.

Groove Is In The Part

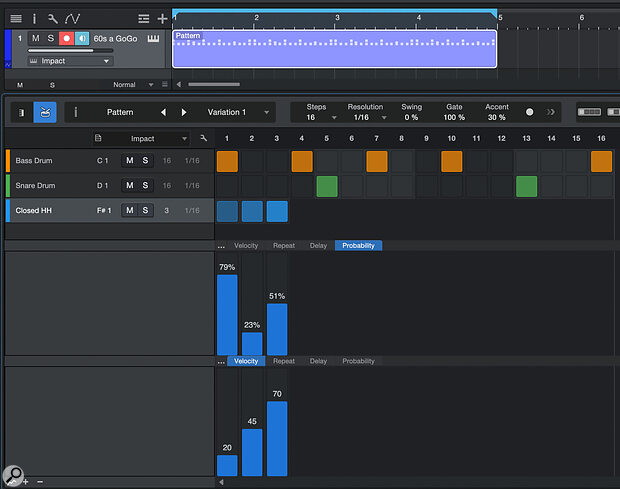

Most modern DAW sequencers incorporate a parameter for probability, or chance, to determine the likelihood that a programmed note will sound on any given pass through the pattern. One way to use this musically is to reduce the probability of a steady part, like a 16th‑note hi‑hat, from occurring on every subdivision (Screen 2). The continual variations will undoubtedly yield interesting syncopated and funky patterns.

Screen 2: The varying probability amounts on each hi‑hat note generate continual rhythmic variations.

Screen 2: The varying probability amounts on each hi‑hat note generate continual rhythmic variations.

Another feature of modern step sequencers is the ability to set unique numbers of steps for each lane. Combining this feature with varying probability generates evolving rhythms using a much smaller set of steps. Varying the velocities leads to interesting ghosted and accented notes falling on different subdivisions.

In the example in Screen 3, I’ve taken a simple three‑step lane of hi‑hat notes with varying velocities and probability percentages. The result is a funky and evolving hi‑hat part.

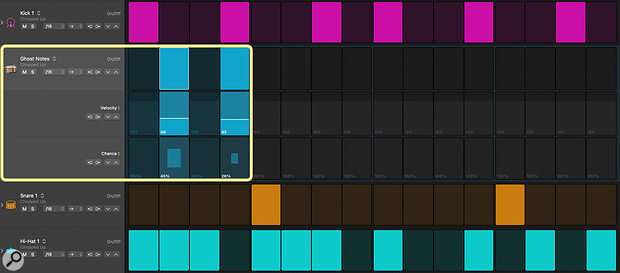

Screen 3: A looping lane of three steps generates an evolving hi‑hat part containing accented and ghost notes.

Screen 3: A looping lane of three steps generates an evolving hi‑hat part containing accented and ghost notes.

Haunted Rhythms

Ghost notes are a large part of the intangible human element that live drummers bring to the art of drumming and grooving. After programming a basic groove, set up an additional lane with either a duplicate of your snare sample or, even better, an alternate, lower‑intensity snare sound (Screen 4). Set the lane for four steps of 16th notes (assuming a 4/4 beat), and program steps on the second and fourth 16th notes. These are the pulses where ghost notes happen. Set your step sequencer to loop this four‑step lane, and lower the chance (or probability) of the two programmed steps getting triggered on any given pass. The result is randomly generated ghost notes on the second and/or fourth 16th notes of each beat in the bar. Set the step velocity appropriately low so they are much quieter than your principal snare.

Screen 4: A looping four‑step lane incorporating low velocities and low chance generates random ghost notes.

Screen 4: A looping four‑step lane incorporating low velocities and low chance generates random ghost notes.

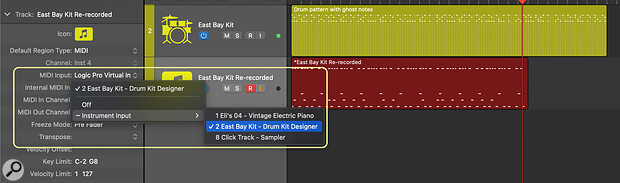

Generating these kinds of random rhythmic variations is great, but sometimes you want or need to capture this lightning in a bottle, to ensure consistent playback of your song. Modern DAWs incorporate features to route or record the output of internal instruments to a new track.

Although the exact procedure may vary slightly from DAW to DAW, the underlying workflow is the same. Extend your pattern, which is likely between one and four bars long, to play for a long enough time to generate plenty of randomly generated variations. Create an additional track to re‑record the output of your pattern playback track. On the new track, set the MIDI input to respond to internal routing rather than external MIDI input (like from a keyboard controller). Then assign it to listen to the output of the pattern playback track, and record the result. You will end up with a constantly varying recorded part. Pick and choose the areas that work best, and copy/paste them where desired.

Idea Generators

So far we’ve been exploring ideas incorporating controlled random elements accompanying structured, predetermined parts as a means of creating variation or adding interest or feel. Taking things a step further, incorporating indeterminate elements may also stimulate ideas and new directions as to the actual structure of the music.

Arpeggiators are generally the antithesis of this goal. Traditionally they spit our regular repeating patterns of notes, usually arpeggios, that remain consistent. However, modern arpeggiators offer a variety of functions that introduce random or chance elements to the sequences of notes generated.

Screen 5: Set the MIDI routing of a new track to capture the output of a pattern‑generating track incorporating chance elements, and record the results for further use.

Screen 5: Set the MIDI routing of a new track to capture the output of a pattern‑generating track incorporating chance elements, and record the results for further use.

For example, the Probability Arp in UVI’s Falcon software synthesizer offers control over the percentage chance that generated notes will jump to another octave, be repeated, skipped, panned or accented. The generated notes can conform to a specified tonal centre, scale or mode. Slowing the speed down from the traditional eighth‑ or 16th‑note arpeggiated patterns we expect, the result is the opposite of a regularly recurring sequence of notes.

The notes generated are often interesting re‑ordered sequences that would not otherwise be considered. Recording the MIDI output in your DAW, as described earlier in this article, is a great way of capturing the magic. Once in your DAW, extract the best segments for development in a more controlled manner. Alternatively, use the evolving sequence of notes to accompany more regularly repeating parts, handing over some of the compositional aspects of the music to chance, if that is your thing.

Many software instruments, like UVI’s Falcon, also provide tools for capturing the generated notes directly onto the source track.

Latch mode, which allows the arpeggiator to run until new input is received, is an interesting function that allows for a random and improvisational performative approach. Start a multi‑note pattern, ideally with some silent steps, then stop and start different notes as the arpeggiator plays. The result is an evolving part incorporating change in real time, at the discretion of the performer.

Incorporating chance elements in part creation is a great way to stimulate production ideas.

From Micro To Macro

Incorporating chance elements in part creation is a great way to stimulate production ideas. There are plenty of tools available to help with the actual composition of the underlying music itself using chance procedures. Two such tools were introduced in the recent Kontakt 8 update from Native Instruments. One focuses on harmony, the other on melody.

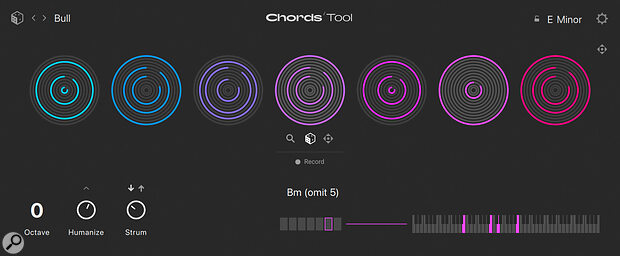

The Chords Tool can stimulate harmonic ideas to enhance or expand the harmonic movement in your music (Screen 6). If you are a beat‑maker, and stick close to a single simple tonal centre, Chords suggests related harmonies. Even if you are an experienced player, it often suggests ideas that lead to potential new and interesting directions in your song’s development. And if you don’t like the choices offered, the individual chord suggestions are easily randomised with a click of the dice button.

Screen 6: The Chords tool in Kontakt 8 offers harmonic suggestions related to the key and tonality of your music.

Screen 6: The Chords tool in Kontakt 8 offers harmonic suggestions related to the key and tonality of your music.

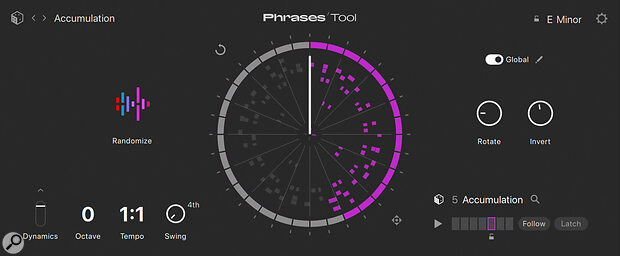

The Kontakt 8 Phrases tool (Screen 7) is perhaps the most intuitive ‘idea generator’ I have ever used. It is an unconventional, original interface, which helps free your brain from the tyranny and habit of your preconceived ways of working. Tied to a defined key and scale or mode, each bank contains eight related melodic phrase ideas. Edit functions allow you to rotate, invert, reverse and limit the sequence of notes, resulting in virtually infinite variations. Randomise buttons throughout the interface enable more experimentation if these functions don’t yield enough ideas. Often just a few notes are needed for a useful hook, melody, or thematic motif.

Screen 7: The Phrases tool in Kontakt 8 yields virtually limitless variations of generated melodic ideas.

Screen 7: The Phrases tool in Kontakt 8 yields virtually limitless variations of generated melodic ideas.

If you are not a Kontakt 8 user, don’t worry. Modern pattern/step sequencers and arpeggiators all contain functions for inverting playback direction and speed, offsetting individual lanes, skipping and repeating steps, and more.

Screen 8: An arpeggiator focusing on shape and contour instead of pitch and harmony yields interesting results.Any tool that takes you out of your traditional mindset stimulates you to think differently about how and what you are creating. Modalics are interesting disruptors. Their Eon Arp plug‑in reimagines what an arpeggiator is and does, and how you interact with it (Screen 8). Simple MIDI input is transformed into unique and imaginative melodies and chord patterns. The note grid takes incoming chords and spreads them vertically by scale degree. This takes you out of the traditional ‘pitch and harmony’ mindset and gets you thinking about the contour and movement of the parts. You draw shapes and patterns rather than sequence notes. The results are always stimulating.

Screen 8: An arpeggiator focusing on shape and contour instead of pitch and harmony yields interesting results.Any tool that takes you out of your traditional mindset stimulates you to think differently about how and what you are creating. Modalics are interesting disruptors. Their Eon Arp plug‑in reimagines what an arpeggiator is and does, and how you interact with it (Screen 8). Simple MIDI input is transformed into unique and imaginative melodies and chord patterns. The note grid takes incoming chords and spreads them vertically by scale degree. This takes you out of the traditional ‘pitch and harmony’ mindset and gets you thinking about the contour and movement of the parts. You draw shapes and patterns rather than sequence notes. The results are always stimulating.

Performance

Incorporating chance to generate ideas or vary individual parts are two areas of music creation. However, there is a performance aspect that can benefit from a loosely structured, non‑linear approach. In other words, the musical components are in some way predetermined, leaving the choice of which to play or in what order to be determined in real time.

Like most new technologies, DAWs began their life imitating the older technologies on which they were based — multitrack tape machines. In the digital age, we have grown up working with a tape‑like timeline where music is organised vertically on tracks flowing horizontally from left to right. Over the last several years a non‑linear approach to organising parts has been introduced in most of the major DAWs. Pro Tools has Sketch, Studio One the Launcher, and Logic Pro has Live Loops. And Ableton Live was conceived this way from its inception.

Freed from the linear tyranny of verse/ pre‑chorus/ chorus thinking, a more open form of arranging emerges with these new tools where different sections and combinations of parts are triggered independently in real time. So each performance is different. In essence, we are ‘playing’ our DAWs and improvising arrangements.

Musical monads, or building blocks, are stored in cells rather than linear‑based clips, events or regions. Cells are organised into scenes. This mindset is great for making beats, where it is simple to drop different elements in or out on the fly.

However, the non‑linear approach these grid‑based environments bring also encourages experimentation with traditional song‑based arranging. Give the same grid to different artists, and they will each trigger scenes and cells in unique combinations. While performing this live triggering, it is also optionally captured in the linear timeline, so further tweaking beyond the initial improvised performance is possible. So we get the best of both worlds — improvisation and chance combinations, combined with the ability to edit the results.

The aleatoric approach to creating individual parts, composition and arranging, can easily become chaotic and uncontrolled. But applied sparingly, and combined with other techniques, it becomes a powerful and stimulating creative device to spur your imagination, kicking and screaming at times, in new directions.