Legendary US record producer Bob Clearmountain undoubtedly has his name on more hit records than anyone else in the history of popular music. Dave Lockwood asks the man who invented the role of 'specialist hit mixer' to reveal the secrets of his success.

Bob Clearmountain has a career credits list that reads like a Who's Who of rock music since the mid‑'70s. Starting out as an assistant engineer, he soon followed the logical career progression to engineer and then to the producer's chair, before becoming perhaps the record industry's first acknowledged specialist mixing engineer. Clearmountain obviously settled very comfortably into the role — he readily admits that he enjoys the mixing stage far more than doing the whole producer's job — turning out a seemingly endless string of hits through the '80s and '90s. Indeed, there was a time when it almost seemed as if nobody but Bob Clearmountain could mix rock albums that would become international best sellers, and I would guess that there are few record buyers with collections running to three figures who don't actually possess something with his name on it.

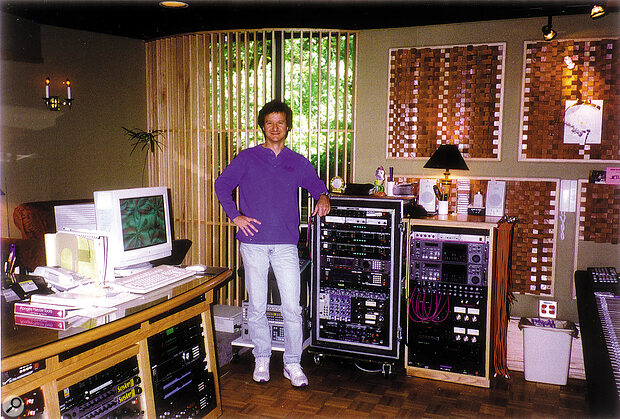

Despite the prominence of his work, however, for much of his career, he has seemed something of a reclusive figure, rarely interviewed, and photographed still less. I have to admit, I always imagined that this was a cultivated image, maintaining an air of mystery to perpetuate the idea of the golden‑eared hit maker with the magic touch on the faders. The reality, sitting across the table from me, dispels the myth immediately. Clearmountain is quietly spoken, disarmingly frank about his apprehension at the prospect of being interviewed, but above all he comes across as entirely without pretension — almost humble in the way he speaks of his own achievements

He is happy to talk about his mixing techniques, however, despite seeming genuinely surprised at the idea that anybody might be interested in his views on the matter! On the surface, the 'method that launched a thousand hits' appears to amount to no more than: mix quickly; don't listen to any part in isolation for too long; mix quietly on small speakers; and take a break now and again! It's typically Clearmountain that he should want to so understate his contribution. The reality is that the true artistry in his work lies in his ability to get inside a song, a lyric, an artist, to bring out everything that needs to be there and nothing that doesn't, thereby allowing the work to properly communicate to the listener whatever it is that it has to offer. And not just once, not just with a small clique of people that he happens to connect with, but time after time, with a succession of different artists encompassing an extraordinary range of musical genres. That, I believe, takes a rare sensitivity and a quite unique talent.

Fast Track In

Like many others who ended up achieving fame 'on the other side of the glass', Bob Clearmountain actually began his musical career by playing in a band. "I was a bass player. Just bar bands though — I never made a record or anything like that. But the last band I was in, when I was 19 years old, was doing a demo in a studio in New York, around '72. But the band split up — the lead singer's girlfriend was getting a little too friendly with the guitar player, or something! So, even though most of my friends were musicians, I found myself thinking that I didn't really want to be depending on these people for my career. The first time I walked into a professional recording studio I immediately thought, 'Wow, I could live in this place' — I was always the guy in the band with the tape machine recording the gigs, and I was always interested in that side of things. I even had a little makeshift studio in the basement of my parents' house — just a little two‑track reel‑to‑reel, a couple of microphones and a talkback.

"So I started out by hanging around the studio where we'd been doing the demo [a now defunct studio called Media Sound on New York's 57th Street], and I just hassled them to hire me. I told them 'I'm going to be good at this someday. You should really hire me.' After a couple of months of this, they finally did — mostly, I think, because they wanted me to stop bugging them! They hired me as a runner, doing deliveries for them, and I figured I'd probably be doing this for a year or two at least. But they only sent me out on two deliveries, and when I came back the office people were saying 'Where's that Clearmountain guy? He's supposed to be on a session. Hey, we've been looking all over for you. You're not supposed to be a runner, we need you to be an assistant engineer'. So I'm thinking, 'Wow, that's quick. An hour and a half!'

"They said 'You're supposed to be in studio A.' So I get down there and it's a Duke Ellington session. I'm 19 years old and I've never even met anyone famous before, and I'm working on a Duke Ellington session. I was an assistant for a while, but really quickly I started engineering sessions myself. I was supposed to be assisting on a session with Kool and the Gang, but it turned out that the engineer had a problem with black people and he said 'Maybe you should do this session.' Actually, Ron Bell, the leader of the band, was just about the nicest guy you could ever imagine, and he and I hit it off just great; I ended up doing several albums with them.

I just hassled them to hire me. I told them 'I'm going to be good at this someday. You should really hire me.

"The studio had a 16‑track machine — an enormous Ampex MM1000 — and the console was actually a thrown‑together, almost homemade thing, based on a Spectrasonics, and not particularly good‑sounding. But all the gear was so basic in those days that you always had to augment it. You couldn't just use the desk, like they do now, you really had to use the outboard. The first thing I would do would be to turn all the EQs all the way up at 10kHz because the desk was inherently dull‑sounding. So I'd always show up early in the morning and collect up all this outboard gear from the other rooms — the studio had a whole lot of Pultec EQs — and pile them all up in my room. You kinda had to squeeze and coax the sound out of the equipment then, whereas nowadays it's quite a bit easier because most equipment sounds pretty good just on its own.

"I did a lot of jingles, where you'd have to work really quickly. You'd have a rhythm section and a horn section, and have to be ready to go for a take within the first 10 or 15 minutes. It was really good training for me to get to work with a lot of different types of music, too, and eventually I moved on to become Chief Engineer at a studio called The Power Station, which opened up in about 1977 or '78. In fact, I assisted in designing the place and helped to turn it into a rock studio."

Station Master

Clearmountain's long‑standing preference for mixing on Solid State Logic consoles is well enough known — surprisingly, however, the association actually goes right back to the company's early days. "I did a lot of records with a band called Chic, and we did a session out at a studio in Burbank that for some reason had an SSL B Series, and I just loved it. I had never heard of this company before, but I just thought it was fantastic. It was so much easier to use than most other desks around then — it seemed like it was designed by people who actually did mixing rather than by traditional console designers. Then when SSL came out with the E Series, and I was involved in specifying the equipment for The Power Station, we ended up getting the first SSL E Series in the USA, so I started using that. It was an in‑line desk and it just did a lot more than other desks at the time.

You had to be really careful with the EQ — it was easy to get them to sound harsh if you EQed too much — although in some ways they were actually more open on the top end than other desks. We still used a lot of outboard EQ — Power Station had 24 Pultec EQs in each room, so mostly we'd use those. But the thing about the SSL was that it had the automation. These days it would seem pretty crude, but for the time it was really advanced. It actually took a lot more work to use the automation back then, but the system obviously got a lot better over the years.

Bob's been a fan and user of SSL consoles since what seems like forever.

Bob's been a fan and user of SSL consoles since what seems like forever.

"At Power Station we were doing a lot of New York punk rock bands, like The Ramones and Talking Heads. There was one New York band I was involved with called the Tuff Darts which never really got any place, but they were friends with Ian Hunter from Mott The Hoople and he came in and did some stuff for them on their album that I was producing for them, and that's how we became friends. He did one of his solo albums there, called You're Never Alone With A Schizophrenic, for which he hired Bruce Springsteen's E Street Band as the backing band. That's how I got to know them, and they went back to Bruce, who was working at Record Plant, and said 'You've gotta check out this studio. It's fantastic. It's got a big open drum room that's really live and it's a really fun place to play.' So Bruce came over and he did The River [his 1978 album] there. I started him off with it — we did a couple of sessions, but then I had to go off and do something else, as I was starting to work as a producer by then".

Clearmountain had, in fact, already started to be brought into projects just for the mix — very unusual at the time — having been requested to mix The Stones' 'Miss You' single. "That all came about because of the records I'd done with Chic. They were an incredibly successful act for Atlantic Records, and both Roxy Music and The Stones were on Atlantic and I think they both wanted to get into the dance market more. So I was recommended to both of them and that, and the punk bands and working with Springsteen, was what got me into doing rock music. I also started doing some stuff with A&M and that's how I got introduced to Bryan Adams — he was one of their artists and he needed a producer. He had produced one record on his own, but it didn't do very well — it was a very minor success in Canada, so they hooked us up together. He had a song called 'Lonely Nights', which was a radio hit in the States, and then Cuts Like A Knife did pretty well, and Reckless sold something like 11 million copies, so that situation just sort of grew. For Roxy Music, I mixed 'Dance Away' from Manifesto, then Avalon and Flesh and Blood, and those records did well. I then did a lot more stuff with the Stones and Springsteen, and then I co‑produced Simple Minds and The Pretenders, and both those records were quite successful."

Clearmountain had, in fact, already started to be brought into projects just for the mix — very unusual at the time — having been requested to mix The Stones' 'Miss You' single. "That all came about because of the records I'd done with Chic. They were an incredibly successful act for Atlantic Records, and both Roxy Music and The Stones were on Atlantic and I think they both wanted to get into the dance market more. So I was recommended to both of them and that, and the punk bands and working with Springsteen, was what got me into doing rock music. I also started doing some stuff with A&M and that's how I got introduced to Bryan Adams — he was one of their artists and he needed a producer. He had produced one record on his own, but it didn't do very well — it was a very minor success in Canada, so they hooked us up together. He had a song called 'Lonely Nights', which was a radio hit in the States, and then Cuts Like A Knife did pretty well, and Reckless sold something like 11 million copies, so that situation just sort of grew. For Roxy Music, I mixed 'Dance Away' from Manifesto, then Avalon and Flesh and Blood, and those records did well. I then did a lot more stuff with the Stones and Springsteen, and then I co‑produced Simple Minds and The Pretenders, and both those records were quite successful."

Producing The Mix

To some producers, the recording and mixing stages are almost indivisible, with decisions taken at the recording stage to some extent predetermining what can be achieved at the mix. Clearmountain, however, sees drawbacks as well as benefits in this way of thinking. "I find if I've produced a record, sometimes it's hard to see the forest for the trees when I'm mixing. It's harder to be objective, because you know every note and every nuance. I find that when you remember what it was like to get the guitar player to play that solo, and the singer to give that vocal performance, you tend to feature things with that in mind. When I mix something I've never heard before, it's a clean slate, because I have no prior connection to it. It's easier and it's also quite a bit more fun, because different producers and different artists have different styles, and that makes it much more of a learning experience for me. It means that each time I mix a record I might have to do something new, because what's on the tape is different. I love switching between types and styles of music. It keeps it fresh for me because I have to constantly come up with new approaches and new ways of doing things. And I think I'm a better mixer than I was a producer, and it's probably better to be doing what you're best at."

Clearmountain takes a very song‑based, almost 'holistic' approach to building his mixes. "I usually try to put everything up at once and do a rough mix to listen to, just to see what's going on. With pop music, I tend to focus on the lyric and the lead vocal more than anything else, trying to get a sense of what the song is. That matters more than anything; more than what the drums or guitars are doing, although I know a lot of people tend to start with the drums and the rhythm parts. I tend to start with the vocals, and then I might get into guitars and keyboards. I'll try to find effective pan settings for everything, thinking of it like a stage. Then I'll get a basic drum balance and build from there, but not really in any predetermined order. It all depends on the track. Once I've got a rough mix, then I'll go through it again and solo individual tracks until I get a really good idea of what's on each one and what the 'role' of each part is. I like to think of the instruments as characters, assessing what their contribution is, and what each thing adds to the song.

"If anything, I tend to not solo things enough — that's one of my problems — so every once in a while there will be some rogue sound that gets left in there and someone will say 'What's that noise on there?' and I'll have to go and find it. Of course, I always try to get rid of that stuff, but I'm usually so into the song, especially if it's a good song, that I just wanna hear the whole thing sounding right, so I tend to not focus on any one particular thing too much. I won't sit there and listen to the bass drum for six passes. I just listen to it for a little bit and say 'that's great', and then I'll listen to something else and keep jumping around until something sticks out and obviously isn't working, then I'll maybe go and EQ it. If I find that I'm missing stuff, or it's not sounding present enough, I might try a couple of different compressors.

"I'll tend to use the automation to write extensive rides on the vocal faders to make sure that the vocal can always be heard, rather than using compression. I might compress for the sound, to get a certain kind of effect, but not to level it. I have some old UREI LA3A compressors which have been modified to reduce the noise, and I use a UREI 1176 sometimes, and I have these [Empirical Labs] Distressor units that are pretty cool for certain types of things. Sometimes I'll just use a little bit of compression and sometimes I'll smash it. It all depends on what it needs; singers are all so different. I also like the BSS Dynamic Equaliser — sometimes you'll get a harshness on certain notes in a vocal, and with the BSS you can find where the harshness is occurring and it will just dip it out at the times when it's needed, and the rest of the time it won't be doing anything. That's a real useful device.

"I generally work on the vocal first. After I've written the basic cuts, I'll get a good rough mix and then I'll put in some vocal rides in the first pass with the computer. The first pass is the critical thing to me. In the '70s, when we were recording on analogue with no automation — I did hundreds, maybe thousands of mixes that way — we would mix sections and then edit them all together, and I tend to work pretty much the same way on the computer. I'll try to get almost like a live mix happening and I'll try to get each section sounding right until I have a complete pass that is a pretty good basic mix. Then I'll just keep going along until I hear something that sounds out of place and go back and grab it. After that, I'll go in and get the details and really fix things up, like perhaps where I'm missing one word and it needs a ride just for that.

"Once I've built the rest of the mix, I'll occasionally find that the vocal just isn't really working any more. Then I'll often do a complete pass from scratch, rather than try to fix it up. Sometimes that's just easier. I generally try to do everything as quickly as possible. Every now and then I'll work with somebody like Mutt Lange [the pair worked together on two Bryan Adams albums: Waking Up The Neighbours and 18 'Till I Die] who will spend all day just riding one vocal. At the end of the day you turn on the fader motors [interestingly, Clearmountain prefers to do all his mixing work with the motors switched off] and the faders will look like they're vibrating! Don't get me wrong, I think he's an amazingly talented producer, but that can get pretty intense. I'm normally somewhere in between just letting everything be, and Mutt!"

Divine Ills

Unless the artist has indicated in advance any specific direction that they are seeking, Clearmountain prefers to start a mix with no preconceived notion of how it should sound — "I like to just let a mix develop, and these days most people will say 'We just want to see what you come up with.' If I come up with things they like, then great. Sometimes, though, they'll say, 'No , that's not it at all.' When I was mixing 'The Seeds Of Love' for Roland Orzabal from Tears For Fears, he listened to what I'd done and said... 'That's absolutely nothing like what I had in mind!' So I just had to say, 'OK, point me in the right direction.' He gave me some clues and I worked on it for another couple of hours and then he said...'No!' — so we moved on to another song!

"I actually enjoy other people's input into the process. I'm absolutely not one of those guys that says 'I'll mix the record. You go away and I'll send it to you.' I want to hear what they have to say. I want their impression of who they are, because it's not my record, I'm just there to bring out the best in the artist. I worked with an Australian band called The Divinyls, and this was when I'd just finished mixing Avalon for Roxy Music, which was this big, lush beautiful thing with delays and reverbs everywhere. But they were more like a punk rock band, very rough and jagged sounding. So I'm mixing this thing for them and and I'm making it all big and lush and wide and hi‑fi‑sounding. When we got to the second mix they took me aside and said, 'Look, you gotta understand, we're not Roxy Music. We're like a small ball with spikes coming out of it. Compact and jagged and annoying.' So I go back and listen to what I'm doing and I think, 'Yeah, that's exactly what they are. What the hell was I doing with this?' So I just started over with that in mind, and then I totally got it. It was so great what they did — instead of us having this big, 'I'm the one mixing this record and you don't know what you're talking about,' thing, it was 'Yes, you're absolutely right.' And that's the essence of what I'm about."

I make records for the general public. I don't make records for audiophiles — I'm sure they don't listen to my records. They'd probably be appalled by what I do.

It's an approach that has proved spectactularly successful, of course, both commercially and artistically. Yet Clearmountain certainly doesn't feel that it is necessary for him to personally enjoy everything that he's asked to mix. "Its easier for me when I do enjoy it — those times when I love the music and I'm having such a good time being part of it that I feel like I'm hovering over the console — but then there are times when I sit there and think 'What the hell is this? Why did I say I would mix this? This is terrible!' But even then it really doesn't matter, because I just start thinking about the sounds that are on the tape and the balance and I can still totally get into it. Even if I don't like the music, there will be something about it that I will like or that I can work off. I think of this as being rather like an actor — he doesn't necessarily have to identify with the role, he just has to figure out what the part is about and be able to be that character. It's the same with mixing. You just have to figure out what the thing is about and who it's for — you just have to be able to put yourself in the position of whoever you think the potential audience is, and then you can transform yourself into thinking in the right way about it. And then I will actually start to enjoy it — I mixed an Engelbert Humperdinck record once! I wouldn't choose to listen to that if it was the last record on earth, but I just thought about the audience that it was for and it came out great. It's not always about listening to a record for enjoyment."

It's an approach that has proved spectactularly successful, of course, both commercially and artistically. Yet Clearmountain certainly doesn't feel that it is necessary for him to personally enjoy everything that he's asked to mix. "Its easier for me when I do enjoy it — those times when I love the music and I'm having such a good time being part of it that I feel like I'm hovering over the console — but then there are times when I sit there and think 'What the hell is this? Why did I say I would mix this? This is terrible!' But even then it really doesn't matter, because I just start thinking about the sounds that are on the tape and the balance and I can still totally get into it. Even if I don't like the music, there will be something about it that I will like or that I can work off. I think of this as being rather like an actor — he doesn't necessarily have to identify with the role, he just has to figure out what the part is about and be able to be that character. It's the same with mixing. You just have to figure out what the thing is about and who it's for — you just have to be able to put yourself in the position of whoever you think the potential audience is, and then you can transform yourself into thinking in the right way about it. And then I will actually start to enjoy it — I mixed an Engelbert Humperdinck record once! I wouldn't choose to listen to that if it was the last record on earth, but I just thought about the audience that it was for and it came out great. It's not always about listening to a record for enjoyment."

Clearmountain's main monitors in his mixing room are Yamaha NS10s — "I just know them so well that I can really be sure of what's going on with a mix when I use them," — augmented by self‑powered KRK E7s — "those let me hear what's happening below 80Hz." He also employs a pair of compact Apple computer speakers. "Those are actually my favourites! I have them placed right next to each other at the side of the room on top of a rack. I don't like speakers that are too hi‑fi for mixing, because if the speaker makes everything sound good, you don't work as hard and then the mix is not going to sound very good when you play it back on a lesser speaker. I want something that makes me work hard. I like to switch speakers a lot, as well. The little ones, believe it or not, are actually really good for judging things like bass and bass drum level. If I can't hear those on the little Apple speakers, then I know I've got to re‑EQ or change something in the track. They're also good for setting vocal levels. There's just no hype with the little ones — they're so close together that everything is almost mono, and I get a really clear perspective of how the overall thing sounds. Of course, they don't make them any more. Anything that's good, they always stop making it.

Clearmountain's main monitors in his mixing room are Yamaha NS10s — "I just know them so well that I can really be sure of what's going on with a mix when I use them," — augmented by self‑powered KRK E7s — "those let me hear what's happening below 80Hz." He also employs a pair of compact Apple computer speakers. "Those are actually my favourites! I have them placed right next to each other at the side of the room on top of a rack. I don't like speakers that are too hi‑fi for mixing, because if the speaker makes everything sound good, you don't work as hard and then the mix is not going to sound very good when you play it back on a lesser speaker. I want something that makes me work hard. I like to switch speakers a lot, as well. The little ones, believe it or not, are actually really good for judging things like bass and bass drum level. If I can't hear those on the little Apple speakers, then I know I've got to re‑EQ or change something in the track. They're also good for setting vocal levels. There's just no hype with the little ones — they're so close together that everything is almost mono, and I get a really clear perspective of how the overall thing sounds. Of course, they don't make them any more. Anything that's good, they always stop making it.

"I switch my monitor levels all the time too — I tell people I work with, 'Just give that monitor pot a spin any time you like.' But I do most of my mixing work at a pretty low level. I get a better perspective that way and I can work longer. If I can get a sense of power — emotional power or sound‑power — out of a mix when it's quiet, then I know that's gonna still be there when I turn it up. I'll use headphones occasionally, too, and I have AES lines that run up to my den, and I have a couple of little Tannoy bookshelf speakers up there so I can go up there and listen. The trick is keeping perspective, and I like to get as many different perspectives as possible."

Clearmountain is certainly not one to agonise over a mix, usually expecting to wrap it up within a day: "The most I'll do is leave it overnight and then come in the next morning to finish it up. The basic mix will always be there though — a balance is a balance — so any changes at that stage will just be things like a bit of EQ, or effects levels. Is it too wet? Should it be wetter? But if I work for two days on a mix I can't really tell any more. I just start to lose perspective. Normally it won't take that long — sometimes I'll finish it before dinner."

The real problem is that there are just too many people making records who shouldn't be making records.

Pick Of The Crop

My enquiry as to which of the many Clearmountain hit mixes he feels represents his best work seems to have him momentarily unsure, as if not certain that he has actually ever done anything that he could be proud of. "Oh, I guess it's the stuff that is a little different that I'm most attracted to — anything where the songs are good and the sounds are interesting. Perhaps Aimee Mann's first solo album, Whatever. I don't know if anyone even heard that record in Europe — hardly anyone knows it in the States! It sounds really unusual and the songs are great. She's one of the most under‑rated songwriters in the business — I'm actually finishing mixing her third solo album when I get back to the States and that's just stunning."

My enquiry as to which of the many Clearmountain hit mixes he feels represents his best work seems to have him momentarily unsure, as if not certain that he has actually ever done anything that he could be proud of. "Oh, I guess it's the stuff that is a little different that I'm most attracted to — anything where the songs are good and the sounds are interesting. Perhaps Aimee Mann's first solo album, Whatever. I don't know if anyone even heard that record in Europe — hardly anyone knows it in the States! It sounds really unusual and the songs are great. She's one of the most under‑rated songwriters in the business — I'm actually finishing mixing her third solo album when I get back to the States and that's just stunning."

"I liked the Crowded House records too — I think Neil Finn is just brilliant — and there was a Squeeze album, called Play, mixed at Real World, that I was quite happy with... And, of course, Roxy Music's Avalon. I was pretty happy with that, but listening to it now, I'd do it completely different. I used too much reverb on that. Also, I just mixed this record for this 19‑year‑old kid named Jesse Camp who won a contest to be an MTV VJ in New York. It's very hard rock, very 'gnarly' and '70s punk rock‑sounding, but it's really good. It's a totally unpretentious album of fun pop songs. Loud and irritating!"

'Loud', maybe, but 'irritating' is not a quality that I readily associate with the glossy, detailed Clearmountain mixes that I'm familiar with. Yet perhaps, in a way, that is the measure of his work as a mixer — the ability to hop nimbly from genre to genre, creating the definitive version of whatever it is that each piece needs to be. To do that continuously for the best part of two decades, I believe, makes Clearmountain himself one of the true artists of the recording era.

Mixing For Surround

"Bryan Adams did an MTV Unplugged which we made an album out of, although A&M didn't actually put it out in surround. The show was one where they played in the round, all facing each other, with the camera perspective from the centre looking out at them. I enjoyed mixing that in surround because there was a reason for things in the audio to be placed where they were. Most music, though, isn't like that. All of a sudden this guitar just comes out from over your left shoulder and you're thinking 'Whoa, what's that doing there?' Maybe this is just my perspective, but I think that when you start using the surround channels for anything more than ambience, it starts to sound very unrealistic.

"I really haven't been asked to do anything for 5.1 yet — most of the people who are asking me to mix their stuff are just desperate to get their stuff played on the radio and that's all they're thinking about — but when I do get to mix for surround I think I'll mostly be using the rear speakers just for effects. I use QSound for that kind of thing at the moment — I don't even tell people I'm using it, because they won't even notice the effect at all unless they are sitting in the right place and the speakers are set up correctly. Just every now and then I like to have some little sound on a record that comes out right over there. If you get the effect, it's like 'Wow, what was that?' Usually the sounds I put through it are very mid‑rangey — I wouldn't put an acoustic guitar or vocals through it, because the process doesn't do much with treble, so you tend to get the top‑end still coming out of the front and the mid‑range coming out over there someplace. But if you just get some little sound like a filtered voice or effect, it can be quite dramatic.

"To me, that's what surround ought to get used for, as well as ambience and making the space a little bigger. But it's really tricky to use it well. There's something funny about having that centre speaker — every time I put something in the centre, it just sounds like it's coming out of a speaker rather than creating the illusion of it being real, whereas with stereo you get this phantom image which somehow sounds more real. The potential advantage of a surround system is that it ought to be able to make things sound more realistic, to make it seem like you are actually there, but maybe it can't do that until someone invents a signal processor that creates more of a seamless illusion between all the speakers.

"But I have a feeling the record buyer doesn't really care if it's surround, stereo or even mono — that's just an audiophile thing. I mean, how many people even sit down in one spot to listen to a record? I don't even do that myself. I'll put on a record and I'll be in the kitchen getting something to eat or just walking around doing something. Half the time people have got their speakers out of phase, so what's gonna happen when they're expected to hook up five or six speakers? And how on earth do we expect home users to get levels right between the front and rear speakers? Somebody emailed me this computer program for optimally setting up a 5.1 system, where you measure how big your room is and how far the speakers are away from the walls. You put all these parameters into this thing and it tells you exactly how to set the levels. And I'm thinking, 'Yeah, right, who's gonna do that? Some audiophile geek is probably gonna be totally into it, but that's gonna be it.' I make records for the general public. I don't make records for audiophiles — I'm sure they don't listen to my records. They'd probably be appalled by what I do. People just want to hook up their system and listen to some music. Where are they even gonna put the rear speakers, never mind getting the levels right? And how can we mix for that if we don't know what'll be coming out of those back speakers?"

Remembrance Of Things Past

Clearmountain, who grew up listening to The Beatles, Motown and English rock bands of the late '60s, considers that many of the classic tracks from that era still stand comparison with the best of today's recordings. "I'm completely humbled by those records. When I listen to them now, I think, 'How did they do that in those days?' I try to have all the latest gear in my studio — I have a big SSL G Plus console and all that stuff, but it's more because it's fun to use and you can do things quicker and easier with a digital reverb than you can when you have to go off into the echo chamber and put blankets on the walls." [Ironically, though, Clearmountain actually has two live echo chambers in his studio which he often uses for his main reverbs, finding they impart a unique quality which he is unable to match with a digital processor.]

"All this gear we have today certainly doesn't make the music any better. It doesn't make the records better, it's just that the process of making them becomes easier. And that brings up the situation where you've now got a lot of people out there making records, just because they can, and I think that has hurt the business a lot. Years ago, records were made by musicians, and singers who could sing and producers who knew how to produce records. Nowadays pretty much anybody can throw together something in their front room using a bunch of loops from other people's records — records made by people who actually did know what they were doing — and it'll sound kinda like a record. I take big issue with this. Whatever happened to records made by real recording artists? People with talent that actually have something to say?

"Before I got into this business, when I was listening to records there would always be certain ones that just sounded like people were having a great time in the studio. It just sounded like something was really happening when this went down, and it really made you want to be there. It was so exciting you could feel it coming out of the speakers. And that's the reason I got into the business. I wanted to be there when that was happening. But now you get some guy taking loops off a CD and taking samples off this and that and sitting there with a keyboard and a programmer. Where is the excitement in that? They might have this great groove that you can dance too, but there will never be the same kind of feeling in that record. Go and listen to pretty much any Motown record, listen to The Beatles, listen to The Stones, and you can feel the session. We need to get back to that, where it's not just a product that's all about making money."

Digital Versus Analogue

"I'm not particularly concerned with what recording medium is used for the records I mix, as long as the engineer and producer have a clue as to what they are doing. I actually tend to be more concerned with the quality of the music itself. If it's a great song, it doesn't really matter if it was recorded on a cassette!

"Although the warmth that analogue can add to many recordings is sometimes a big advantage, I've often been frustrated trying to mix soft ballads that have been nearly ruined by the distraction of tape hiss. Dolby SR can help, but it sometimes seems to mess with the bottom end, and I can occasionally hear the noise pumping under the music.

"I do tend to prefer digital recordings because they're usually simpler to mix — it's easier to get elements of the mix to sound as if they're in front of the speakers, as opposed to inside or behind the speakers. The music tends to sound more like it's live than a recording. Of course, having said that, practically all of my favourite records were recorded on analogue tape — go figure!

"When I used to mix to analogue two‑track, although it could sound quite good, I found that the playback off the tape never sounded quite like what I thought I had — the bottom end sort of mushed together and the character of the top end would change slightly, and it was often dependent on the particular formula, or even the batch of tape. Digital can alter the sound slightly, but nowhere near as much, and with a great converter like an Apogee [Clearmountain is a consultant for Apogee], I really don't notice any change to speak of. I guess I'm kind of a control freak,I think, and for the recording medium to be making decisions about the sound of my mix irks me a bit."

Clearmountain On... 24/96

"I was quite happy mixing to DAT with my Apogee 20‑bit AD1000 converter, but then the 24‑bit stuff came along and it did sound better. It sounds smoother and just more present, especially mid‑range stuff like vocals. It's just a bit more musical, more real‑sounding to me — I was actually surprised when I first heard that. When we were beta‑testing the Apogee PSX100 converter, some of the guys from the company came over and we jammed a bit and recorded it at 96kHz through the PSX100 and 48kHz through the AD8000 to compare them. The difference was actually pretty minimal, so I'm not sure that the sample rate is nearly as big a deal as the bit depth. I will probably have to start mixing at 96kHz though, as my mastering engineer, Bob Ludwig, seems to be really into it [Clearmountain is now mixing the new album from US rock artist Edwin McCain at 96k via the PSX100]. But I don't think it's a huge step — only certain things will benefit."

On analogue tape: "I'm kind of a control freak, I think, and for the recording medium to be making decisions about the sound of my mix irks me a bit."

Hints & Tips

Clearmountain's mixing tips for the project studio are as applicable to the guy mixing on a portable cassette multitracker as to the man himself on his giant SSL.

"Don't listen for too long to any one thing. And take a break — don't just keep plugging away at something. When you start to question everything that you're doing and you suddenly don't feel sure what's going on, stop for a while and go and take a walk. I go out with my dog or take a 15‑minute catnap, then come back and have a cup of coffee and it's much more obvious if something is wrong.

"Listening from different places is useful too. I go and sit on the couch at the back of the room, or go outside the room. Listen in the car.

"And make sure you are listening to the whole mix, not just the vocal, the guitar or the snare drum. Don't think that you have to hear every lick — just because you like it and you know it's good, doesn't mean it has to be there. Does it add anything to the song? Is it really an important element of the record? You have to train yourself to listen to the song and not the individual parts, and then things that are wrong will jump out at you. It'll be obvious that there's a part in the second verse that's pulling your ear away from the vocal when the lyric at that point is really important to the song. What that guitar is doing may be really nice, but when it's brought back a little bit in the mix, the overall thing can turn out better."