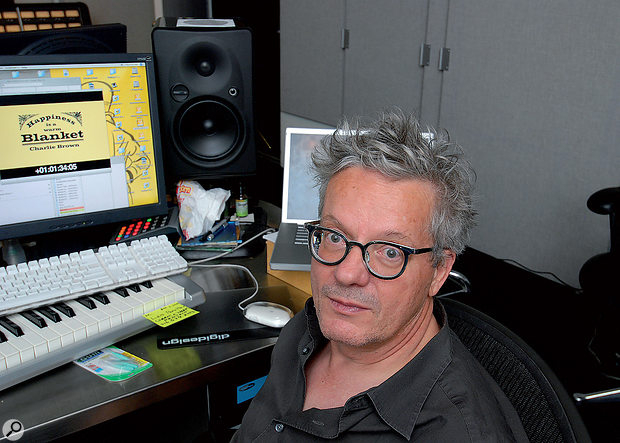

Mark Mothersbaugh.Photo: Mr Bonzai

Mark Mothersbaugh.Photo: Mr Bonzai

Pioneers of everything from circuit bending to multimedia art, Devo have always belonged to the future.

"We were making product for laser discs when we first started off,” says Mark Mothersbaugh. "I remember when [film‑maker and friend of the band] Chuck Statler first came over to where my brother Bob and Jerry [Gerald V Casale] lived, with this popular science magazine. On the cover was a young American couple holding up a 12‑inch record — but this record was silver and shiny, and it said: Laser discs. Everyone will have them by Christmastime. And we were like 'That's it! That's what we want to make product for! Records are over. Rock bands are done for. Pop culture is going to go towards sound and vision. Multi‑faceted artists are going to take the forefront, people who think audio and think visually at the same time.'

"This,” he adds wryly, "was 1974.”

The band that he and Casale founded have spent most of the intervening 36 years waiting for the world to catch up with their ideas. This, after all, was a band who were making music videos before MTV even existed. A band who were making circuit‑bent instruments decades before the term was coined. A band who gleefully ripped away the hippy facade of '70s rock & roll to reveal its true corporate nature.

"We had lots of ideas that were bigger than the reality of the time,” says Mothersbaugh. "But now a lot of that stuff has come into being. Music television is no longer just a weird concept that we were talking about, it's come and gone. Devo is not ahead of our time any more.”

What Producers Bring

On the strength of Something For Everybody, it does indeed seem that Devo and the times are finally in perfect sync. The band's first album of new material in 20 years, it has seen them collaborate with a string of current artists and producers, but their edgy, hard‑hitting synth‑pop hardly needed updating for the 21st Century.

One might expect a band with such a unique — and frequently perverse — artistic vision to act as their own producers, or stick with one producer who understands their ideas. Instead, over the years Devo have employed a series of big names, many of them far from obvious choices for a futuristic synth band. Brian Eno, Ken Scott, Robert Margouleff and Roy Thomas Baker each have a Devo album to their name. "But if you listen to our albums, our album is always the odd band out in their discographies!” protests Mothersbaugh. "Like Roy Thomas Baker: the Oh No! It's Devo album is probably the oddest album in his discography. It probably sounds the least typical of everything.”

Mark Mothersbaugh's studio complex, Mutato Muzika, in West Hollywood.The latest occupant of the hot seat is Greg Kurstin, perhaps best known for his work with Lily Allen (see SOS May 2009: /sos/may09/articles/it_0509.htm). Like most of the other collaborators, his role was mainly to take the basic recordings made by the band at Mothersbaugh's Mutato Muzika complex in West Hollywood, and add his own gloss after the fact. "From a production standpoint, I think one of the more interesting points about this album for the band members was: finally we'd grown up enough that we recognised what a producer could bring to the mix, and we recognised our own limitations more,” admits Mothersbaugh. "So we basically recorded it in my studio in Hollywood, and then we would turn the tracks over to Greg, or Santigold, or whoever it was we were working with. At this point, we really acknowledge what they can bring to it that we can't do on our own. They can make our music sound radio‑friendly, which I really liked.”

Mark Mothersbaugh's studio complex, Mutato Muzika, in West Hollywood.The latest occupant of the hot seat is Greg Kurstin, perhaps best known for his work with Lily Allen (see SOS May 2009: /sos/may09/articles/it_0509.htm). Like most of the other collaborators, his role was mainly to take the basic recordings made by the band at Mothersbaugh's Mutato Muzika complex in West Hollywood, and add his own gloss after the fact. "From a production standpoint, I think one of the more interesting points about this album for the band members was: finally we'd grown up enough that we recognised what a producer could bring to the mix, and we recognised our own limitations more,” admits Mothersbaugh. "So we basically recorded it in my studio in Hollywood, and then we would turn the tracks over to Greg, or Santigold, or whoever it was we were working with. At this point, we really acknowledge what they can bring to it that we can't do on our own. They can make our music sound radio‑friendly, which I really liked.”

In some senses, the production of Something For Everybody also represented a conscious attempt to return to "the way we used to write songs in the old days. We actually did a lot of jamming, believe it or not. We weren't depending on sequencers a lot [in the '70s], because they weren't that flexible, so we would just start off playing things by hand. We would do these long jams, and as we were going Jerry would change a bass part up a little bit and see if he could find a better way to play it or a way that it went more into the pocket, or Alan [Myers, the band's longest‑serving drummer] would change his beat a little bit as we went along. Everybody would be searching for the parts that worked. We did a lot of stuff on four‑tracks where we were trying to make it sound like a song with just the five guys in the band.

"We still own a lot of the old gear that we had, we've kept it through the years, so for about three or four months, I entertained this notion: 'Hey, what do you think if we take the same instruments, use the same kind of setup we had then, and we just write music under the same conditions? Other than that we wouldn't be doing it in a closed‑down carwash, we'd be doing it in a studio in West Hollywood, but what do you say we really limit ourselves from a technological standpoint to the same gear we used in '77, and the same techniques, just jamming and doing things together and see what we come up with?'

The basement area at Mutato Muzika, where Devo rehearse and where much of the new album was recorded. "We kind of tried it a little bit, and it seemed like everyone was not wholeheartedly into it. I thought about it after a while, and I thought: Everybody's resisting it, and I know why. It's because Devo was never about going back and just trying to duplicate something. Every album had its own journey. We were constantly interested in what technology was available. I remember when Roger Linn first made his first Linn Drum machine and we got one of those and put it on our album. The next year we got a Fairlight, and used the Fairlight on that album. Then when Roland put out their sequencers that were mixed into the S50 keyboard, we started using those. We were always moving with the time, and it was kind of disingenuous to try to create this artificial scene. So what ended up being comfortable for everybody, and what we felt was the most true to Devo, was that we used a lot of the gear we used on those early albums, but we also incorporated Pro Tools and took advantage of those techniques, and used sequencing, we used Logic and Digital Performer. Some of those synths were on every single album we did, like the Minimoog, and we pulled a lot of old gear out of closets and brought back an old Oberheim and an old [ARP] Odyssey and an EML synth.”

The basement area at Mutato Muzika, where Devo rehearse and where much of the new album was recorded. "We kind of tried it a little bit, and it seemed like everyone was not wholeheartedly into it. I thought about it after a while, and I thought: Everybody's resisting it, and I know why. It's because Devo was never about going back and just trying to duplicate something. Every album had its own journey. We were constantly interested in what technology was available. I remember when Roger Linn first made his first Linn Drum machine and we got one of those and put it on our album. The next year we got a Fairlight, and used the Fairlight on that album. Then when Roland put out their sequencers that were mixed into the S50 keyboard, we started using those. We were always moving with the time, and it was kind of disingenuous to try to create this artificial scene. So what ended up being comfortable for everybody, and what we felt was the most true to Devo, was that we used a lot of the gear we used on those early albums, but we also incorporated Pro Tools and took advantage of those techniques, and used sequencing, we used Logic and Digital Performer. Some of those synths were on every single album we did, like the Minimoog, and we pulled a lot of old gear out of closets and brought back an old Oberheim and an old [ARP] Odyssey and an EML synth.”

Many of Devo's original vintage instruments were brought out of storage for use on Something For Everybody. From top left: the Minimoog, Mark Mothersaugh's "M16 rifle”; the EML 500, most famously used for the synthesized whipping noise on 'Whip It'; the extremely rare EML Poly‑box; Oberheim Two‑voice and Octave Cat. Even with the 'old school' ethos relaxed, however, the band were still wary of some of the pitfalls that modern technology can lead to. "The plastic flexibility of technology, now, encourages more artists that don't need a band. That's great, but it also changes things quite a bit, and there's something you lose too. If the four or five of us are playing on something, there's a tendency, if it's not right, to think 'You know what, we can add another track.' And you put something else in to help get it where you want it to go. That was one of the things that we consciously were fighting with this album. I know there's a lot of overdubs on it, because our remixers brought a kind of modern, additive synthesis to it, but for the basic parts of the songs, we made a conscious effort. That's one of the things we wanted to capture from our early albums. When we only had a four‑track TEAC to record on, we were like 'OK, the guitar player has to be able to do the solo and leave whatever he's doing and then come back to whatever he's doing to support the song.' So everybody had to constantly be doing something important. That's the side of technology where you get lured into constantly piling stuff on.

Many of Devo's original vintage instruments were brought out of storage for use on Something For Everybody. From top left: the Minimoog, Mark Mothersaugh's "M16 rifle”; the EML 500, most famously used for the synthesized whipping noise on 'Whip It'; the extremely rare EML Poly‑box; Oberheim Two‑voice and Octave Cat. Even with the 'old school' ethos relaxed, however, the band were still wary of some of the pitfalls that modern technology can lead to. "The plastic flexibility of technology, now, encourages more artists that don't need a band. That's great, but it also changes things quite a bit, and there's something you lose too. If the four or five of us are playing on something, there's a tendency, if it's not right, to think 'You know what, we can add another track.' And you put something else in to help get it where you want it to go. That was one of the things that we consciously were fighting with this album. I know there's a lot of overdubs on it, because our remixers brought a kind of modern, additive synthesis to it, but for the basic parts of the songs, we made a conscious effort. That's one of the things we wanted to capture from our early albums. When we only had a four‑track TEAC to record on, we were like 'OK, the guitar player has to be able to do the solo and leave whatever he's doing and then come back to whatever he's doing to support the song.' So everybody had to constantly be doing something important. That's the side of technology where you get lured into constantly piling stuff on.

"The down side of technology, and having lots of it and collecting lots of it, is that you tend to not make up your own sounds any more, because it's easier. When I first noticed it was happening to me was with the DX7. I was really lousy at trying to program a DX7 when they first came out, and I ended up falling back on the pre‑programmed sounds, and that's when I realised that I was being told what colours to use, what palette to use, by tech people somewhere in Japan.

"They're all just tools to get where you want to go, and you don't win if you use all analogue, and you don't win if you use all digital, and you don't win if you use all computer. It's finding what's the right combination for you, and that's the thing that would be trickier when you're a kid now, that I'm probably not thinking about it because I relate to it through the fact that I'm an old geezer. I was around when people started off having to work all day patching things in to get a cool bass sound.”

Early Adopters

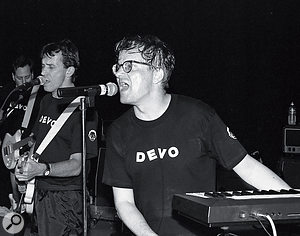

Mark Mothersbaugh has undoubtedly paid his dues when it comes to patching things in. The earliest incarnation of Devo existed as long ago as 1972, and Mothersbaugh, Casale and their bandmates worked almost entirely in isolation until the late '70s, stranded in the rapidly degenerating industrial backwater of Akron, Ohio. "When I was growing up, we were watching the world around us, and it felt like we were in a cultural wasteland. Which we kind of were, from a music standpoint. We had to lie and say we were a Top 40 covers band to get jobs. We were a lightning rod for people's hostility, because we were willing to misrepresent ourselves to club owners just so we could get on a stage, knowing full well that there was going to be some pissed‑off hippies before the night was over.

"I couldn't even imagine what a recording studio was. And I used to look at album covers, and when they showed pictures of the bands in the studio, those were always really interesting to me. It was all so mysterious. Something that really impressed me early on was seeing [the sleeve of] Todd Rundgren's Something/Anything. There was a picture of a multitrack tape recorder sitting in an otherwise empty room, and you knew it was a house. It didn't look like a recording studio, and it wasn't soundproofed, and it had a sliding glass door exactly like you had in an American middle‑class house. I remember being stunned by the concept, once I realised: he recorded this at a house. At the time it was such an amazing idea, because it seemed so liberating.”

Mothersbaugh's own exeriments with home recording began with "when I was really young, finding out that the answering machine on my telephone didn't really make that great a recorder. It obviously brought some things to the mix, like an interesting EQ and limiting and compression that wasn't always predictable, but from an overall sound-quality point of view it limited your range. We slowly worked our way up, and I remember when my brother Bob bought a four‑track and we started using it, it was totally amazing to us. The concept of overdubbing was such an interesting and amazing thing — the idea that we could record the instruments first and then put vocals on top later.”

A Barn Full Of Minimoogs

Even though synthesis was in its infancy when Devo began, Mothersbaugh was already forming his own ideas about how synths should be used, and was lucky enough to own a Minimoog at a time when the technology was truly cutting‑edge.

"I had a couple of friends who were jock football players, and they went over to Vietnam and they came back and they thought they were going to work in the rubber factories, like their dads and their grandads. But while they were in Vietnam fighting for capitalism, the capitalist structure of Akron, Ohio was making a fast getaway to Malaysia and Brazil for cheap labour, and leaving those guys behind. So they came back and they had nothing to do, and they'd learned how to kill people and smoke pot when they were in Vietnam. And they decided: 'We want to start a band, but none of us play an instrument.' So they were using their unemployment cheques, and doing whatever jobs they could, and putting money together and putting together a band, and they asked me if I wanted to play keyboards in their band. And all I had to do to do that was agree to write music. I said 'That sounds pretty good,' and they said 'We can go get you a keyboard if you want, what kind?' So we drove to Buffalo, New York, where Moog used to be, and I remember walking into this barn that had been converted into a warehouse. I remember seeing a rack that was about 30 feet high that had Minimoogs stacked up. It seemed so futuristic.

"The Minimoog kind of became my M16 rifle. That's the synth that, to this day, you could blindfold me and say 'All right, we want a white‑noise puffball with one sine wave wiggling at about 90bpm through the middle of it,' and I could sit there and dial it in. I learned it that well. I was very aware of what was going on with synthesizers, and looked at them lustfully. They were very expensive, and just the fact that I even had a Minimoog was awesome, a really big deal. It wasn't like buying a plug‑in.

"The Minimoog kind of became my M16 rifle. That's the synth that, to this day, you could blindfold me and say 'All right, we want a white‑noise puffball with one sine wave wiggling at about 90bpm through the middle of it,' and I could sit there and dial it in. I learned it that well. I was very aware of what was going on with synthesizers, and looked at them lustfully. They were very expensive, and just the fact that I even had a Minimoog was awesome, a really big deal. It wasn't like buying a plug‑in.

"To me, that was what I was looking for. By the time that Devo started, Jerry and I had met in college already and collaborated on some visual things, and we were there at the protests at Kent, and they shot kids at one of the protests [four students protesting against the Vietnam war were killed by the National Guard at Kent State University, in an infamous incident that inspired the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young song 'Ohio'], and they shut the school down for about four months. We were talking about the world and what we saw going on around us, and decided we were observing de‑evolution, not evolution.”

Subversive Synthesis

In pop and rock music of the time, synthesizers were most prominent in the hands of the prog‑rock acts emerging from Britain. But an angry young Mothersbaugh found it hard to relate to the way they were being used in prog. "I was looking for sounds that I thought were relevant to our place in time — 1971‑2 — and for me it was V2 rockets and mortar blasts, stuff that reflected what I was watching on the evening news. I also wanted to find the sounds that were in the most subversive music that was out at the time, which wasn't anything to do with pop music. It was totally opposite to that: it was TV commercials. Commercials were doing things that were much further out than pop music was. Pop music seemed tame by comparison.

"I wasn't really sold on Rick Wakeman and Keith Emerson and Yes. Bands were all doing bloopy organ sounds. They'd either make mean organ sounds or silly organ sounds, but you could really tell there was a keyboard involved. The first time I heard a synthesizer that I found shocking and inspiring was probably 'Editions Of You' on the first Roxy Music album.”

It wasn't only differences of opinion about synths that set Devo against the mainstream. "I felt that guitar music was running out of things to say in the '70s. To me, concert rock was abandoning what was important about rock & roll in the first place. The politics of concert rock were basically: I'm white, I'm stupid, I'm a conspicuous consumer, I'm a misogynist and I'm proud of it. That's what I felt like music had come to in the mid‑'70s.

"The other music that was big in the mid‑'70s was disco, and it was kind of like a beautiful girl with a great body but no brain. I wanted to be really angry because I hated it, but at the same time I was like 'What kind of synths are they using to get that sound?' I begrudgingly would say: Yeah, the song 'I Was Born To Be Alive' is idiotic, but there are some really cool synth sounds in it. They made some of the best mixes, and the beats were irresistible, even though I was resisting it because I thought it was moronic.”

Democracy In Action

Devo at LA's Record Plant studio on 3rd Street, 1985 (left to right): Alan Myers, Mark Mothersbaugh, Gerald Casale and Bob Casale (engineering), joined by assistant engineer Clive Taylor.Photo: Neil Ricklen

Devo at LA's Record Plant studio on 3rd Street, 1985 (left to right): Alan Myers, Mark Mothersbaugh, Gerald Casale and Bob Casale (engineering), joined by assistant engineer Clive Taylor.Photo: Neil Ricklen

Irresistible beats are much in evidence on Something For Everybody, thanks in part to the band's new‑found willingness to involve remixers and other collaborators. This new openness is, according to Mothersbaugh, a reaction against years of insularity, and perhaps an indication that the world has finally taken on board the band's message. "I used to be so worried that people would misunderstand what we were about — and they did misunderstand what we were about,” says Mothersbaugh. "We had a pugilistic relationship with the press, and it had to be that way, because we were trying to explain what we were doing. We had to protect ourselves, because our record company didn't understand us, and our own managers and agents weren't sure what we were trying to do. So maybe this is our reaction to our insulation that we used to keep around ourselves.”

Having embraced collective creativity after so many years of isolation, Devo are now making up for lost time. When Something For Everybody was in the pipeline, they signed a new deal with Warner Bros, with the aim of exploring some innovative approaches to marketing an album. The entire marketing budget was thus handed over to advertising agency Mother NY, who unleashed their full range of corporate brand‑building techniques; and, Devo being Devo, these advertising exercises were treated as an integral part of the album project itself. The front cover proudly bears a 'Focus Group Approved' sticker, which acknowledges the agency's use of the band's fanbase to choose the track listing; and plans are well advanced for a reality TV series laying bare the triangular relationship between band, record company and agency.

After a long hiatus at the start of the '90s, Devo regrouped in 1996 to play the Lollapalooza festival in LA. Left to right: Bob Casale, Bob Mothersbaugh, Mark Mothersbaugh.It's all grist to the mill of a band who have always seen art and commerce as two sides of the same coin. "The people that we were really inspired by were like Andy Warhol. He was a painter, but he was also a printmaker and he was a photographer, and he was a fashion designer, and he worked with the Velvet Underground and he threw the best parties in Manhattan. I loved the idea that all the different mediums were fair game for his expression. To me, that was a thoroughly modern viewpoint.

After a long hiatus at the start of the '90s, Devo regrouped in 1996 to play the Lollapalooza festival in LA. Left to right: Bob Casale, Bob Mothersbaugh, Mark Mothersbaugh.It's all grist to the mill of a band who have always seen art and commerce as two sides of the same coin. "The people that we were really inspired by were like Andy Warhol. He was a painter, but he was also a printmaker and he was a photographer, and he was a fashion designer, and he worked with the Velvet Underground and he threw the best parties in Manhattan. I loved the idea that all the different mediums were fair game for his expression. To me, that was a thoroughly modern viewpoint.

"We were very aware that when you signed with a record company, they were a corporation. You could pretend you were a hippy and free, but one of the things we learned in our childhood was that the hippies of the '60s became the hip capitalists of the '70s. So we kind of knew how capitalism and democracies worked, and so rather than just pretend that it was something different, we were kind of mocking it and embracing it at the same time. And a lot of people that was rather upsetting to. I remember getting admonished by Neil Young once — I remember him saying 'Why did you guys put merchandise on your liner sleeve for your album? That's not what rock & roll's about!' I was like 'No! To me, that's like the prize in Crackerjack!'”

Now Is A Great Time

It's yet another area where the band were undoubtedly ahead of their time. With CD sales apparently in terminal decline, record companies are relying to an increasing extent on '360 deals', using income from T‑shirt sales and concert tickets to plug the hole. But when Devo tried to present themselves as a multi‑faceted commercial entity, they were met with bemusement. "I remember people snickering when I'd say things like 'On the next album, we won't even have numbers next to the songs. We're going to have corporate logos by each song for whoever the sponsor is for that song. We won't even need a record company any more.' This was 1980 or something. 'OK, I don't know what he's smoking, but not reality.'

"I loved the idea that we had a merchandise sleeve. To me, that was like American comic books: in the last page, there'd be an ad for Burpee's Seeds, or Grit newspaper, whatever that was. I'd never seen a copy in my life, but I knew that if I sent in my name and agreed to sell Grit newspaper to my neighbours, that if I sold this many copies of Grit newspaper I'd get a baseball. If I sold this many I could get a ball bat, if I sold this many I could get a little model boat. And I loved that page in the comics. I would study all those things that were like the icons of what a boy wanted. And that was all the things that were great about my culture, all the rewards of being a kid, the sought‑after things of being a child in the Western world.

"So when we did our album cover we were trying to bring that excitement to the record, so we put the red energy domes and the yellow plastic suits that we designed on it, and flicker buttons or whatever it was that we had that we could sell. We never made much money doing that stuff, because we made such small quantities, and it was so expensive. The record company was uninterested — all they wanted to do was sell vinyl.”

This photo was taken in 1996 at the home of legendary composer and inventor Raymond Scott, shortly before Scott's death. Mark Mothersbaugh now owns Scott's Electronium, the revolutionary keyboardless instrument shown here.Unsurprisingly, Mark Mothersbaugh is upbeat about the revolution that is currently shaking the music business to its foundations. "What does it mean to be an artist in 2010?” he asks. "We were watching the Internet come in and just destroy entertainment as it had been defined in my lifetime, with the pontificating record companies that told you what you needed to do to be successful, or what it meant to be an artist. We watched the Internet disassemble that Trojan horse. That machine, that old model, is gone, and now we're in an age where there's a lot of things that are up for grabs. There's a lot of concepts about what it means to be an artist. If I was a kid and I was thinking about writing music, I think it would be kind of an optimistic time to get into it, because there's a lot of possibilities that are open to everybody now. You could be in detention at high school and write a song using an app on your phone. The field has been levelled in a lot of ways that make it not so exclusionary as it was when I was a kid.”

This photo was taken in 1996 at the home of legendary composer and inventor Raymond Scott, shortly before Scott's death. Mark Mothersbaugh now owns Scott's Electronium, the revolutionary keyboardless instrument shown here.Unsurprisingly, Mark Mothersbaugh is upbeat about the revolution that is currently shaking the music business to its foundations. "What does it mean to be an artist in 2010?” he asks. "We were watching the Internet come in and just destroy entertainment as it had been defined in my lifetime, with the pontificating record companies that told you what you needed to do to be successful, or what it meant to be an artist. We watched the Internet disassemble that Trojan horse. That machine, that old model, is gone, and now we're in an age where there's a lot of things that are up for grabs. There's a lot of concepts about what it means to be an artist. If I was a kid and I was thinking about writing music, I think it would be kind of an optimistic time to get into it, because there's a lot of possibilities that are open to everybody now. You could be in detention at high school and write a song using an app on your phone. The field has been levelled in a lot of ways that make it not so exclusionary as it was when I was a kid.”

But how are musicians supposed to make money in a world where no‑one respects copyright, and everything is available for free if you know where to look? For those who are truly interested in creating works of art, he feels, the possibilities opened up by the new world order outweigh any financial costs. "If you're getting into music because you want to be mega‑rich, or you're trying to be famous — well, then you shouldn't be doing it anyhow. Maybe it's not that important if you do or don't. If nobody ever hears your stuff, who cares?

"But if you're an artist, and you feel obsessive about what you're doing, I think now's a great time, and the Internet is a great medium.”

Devo & Circuit Bending

As the early Devo shaped their sound over years of rehearsal in a disused Akron carwash, Mark Mothersbaugh and the other members took every opportunity to expand the palette of sounds available to them. The few pre‑built synths on the market were colossally expensive, so this uncontrollable urge to experiment was channelled into building their own gear and modifying anything they could get their hands on.

"My brother Jim was the first drummer for Devo, and early on, I was trying to encourage him to come up with something electronic‑sounding on drums. And he invented one of the first electronic drum kits, in like '72‑'73. On his very first electronic drum kit that he built, he took acoustic drums and took guitar pickups, glued them on to the heads, and ran that through a wah‑wah pedal and a fuzz pedal and an echo box, and put that into an amp on stage. So he'd sit there, and he'd have one foot on his kick, and the hi‑hat would be totally closed but it would be going into a wah pedal. He was using the filter on the mic going into the wah‑wah pedal to make an open and closed hi‑hat, and he could get all this articulation on it. It was really crude and it was really scary‑sounding. I don't think I've ever heard anything since that was quite like what his drum kit sounded back in those days. And it was a little bit out of control. Sometimes, by going into this Echoplex and trying to work it while he was playing with the band, it would start regenerating to the point where he couldn't stop it on stage, and he'd have to stop playing so he could turn off the Echoplex.

"But he got so obsessed with electronics that he stopped playing in the band and he just got into modifying all our gear. He was kind of an early circuit‑bender. We'd take toys and he'd figure out ways to put quarter‑inch jacks into them so I could put them in an amp, and he'd do things to the circuitry.”

Jim and Mark Mothersbaugh also built the kit‑based modular synths that are still sold today by the PAiA company. "For 19 bucks you could buy an oscillator from this company in Oklahoma, and then you'd have to solder all the parts together. It was like a little electronic kit project. And then you'd get a VCF and then you'd get an envelope and you'd get another oscillator and a rudimentary patchbay. This stuff was all of the lowest calibre electronics and packaging, but it was so cool because you were custom‑building your own synth. That seemed really space‑age and very liberating, the idea that the pathway of the signal wasn't already predetermined by ARP or Moog or Roland. I was getting to decide: 'I'm going to run through two filters before I go into the envelope, or I'm going to use two envelopes, one on the filter and one on the pitch,' or something like that. That was exciting.

"Now there's this whole thing with circuit‑bending, and to me, these people are such kindred spirits to the early Devo. I know what they're like. I know these guys before I ever meet them. They're all these frustrated, young, really smart kids, who are maybe introverted and probably socially not that well versed, yet they can sit down in the basement for hours with a Speak & Spell and turn it into this chaos machine. They love the chaos, so every single time you touch the button it's never the same, it's unpredictable. I love that whole movement. It's kind of underground, and yet they stick their heads up just enough to put their stuff on eBay, and they sell them stupidly cheap. You get the feeling it was the activity that was important to them: the intellectual process of creating this piece of sound‑making machinery.”

A Home For TONTO

In the 20 years that lapsed between Devo's previous album, Smooth Noodle Maps, and Something For Everybody, Mark Mothersbaugh has built a formidable career as a composer for film and television. He has also created a unique studio in Hollywood, Mutato Muzika, which has become the base for both his media composition and for Devo's recordings — and also something of a home for vintage synths. Mothersbaugh was responsible for rescuing one of the most famous modular systems in the world from obscurity.

"For a while I had TONTO in the basement of my studio,” says Mark Mothersbaugh. "One of the producers for Devo on our Freedom Of Choice album, Bob Margouleff, had built a synthesizer in the early '70s, with Malcom Cecil. It looks like you're standing inside an eyeball that's synth module racks, shaped so that when they all fit together, you're standing inside. It's a very '70s idea of space and the future. When they built it they used the original Moog oscillators and mixed in Buchla components, and a couple of other companies along with it. They had all these giant rack space things that are just one oscillator, the earliest Moog oscillator you could buy.

"Malcolm was an engineer, Bob was a producer, and Bob was producing a movie called Ciao Manhattan. They were looking for something to write the score for Ciao Manhattan on, so they built this thing. It was meant to be a sort of polyphonic synth, and the way they made their polyphonic synth is they had two monophonic keyboards each, so between the two guys they could come up with a four‑note chord. Or one guy could be playing bass and a lead, and the other guy could be playing two‑note chords. Unfortunately, the oscillators were so early in the history of electronic music that they wouldn't stay in pitch, so it didn't really function as a live instrument, but it did get used on lots of albums. When Bob Margouleff produced Stevie Wonder, Stevie used it on a couple of his albums, and then every black funk band wanted to use it. There was at least two album covers of black funk bands from the '70s who posed like they were weightless in outer space in front of it.

"It had been in storage for about 25 years when I opened up my studio in Hollywood, and I happened to talk to Bob. I said 'You want to set it up again? If you and Malcolm want to set it up in the basement here, I have a big room, you could have it rent free, just so we could see TONTO work again.' And they did, and for about a year, maybe two years, those guys forgot what had made them separate as partners, and they stopped bickering for about a year and built this thing.

"People would come over to my studio, and they would spend all day getting one synth sound that they could record on this old, big modular synth. And they'd get it and go 'OK, that's what it was like in the old days? I like the new days!' None of them ever switched over to all analogue after that, but it was fun to have it at the studio for a while.”