Not everyone can afford a 7.1.4 Neumann speaker setup, but perhaps RIME is the next best thing?

If you want to mix Atmos or another immersive music format ‘properly’, the barrier to entry is high. You’ll need a double‑figure number of high‑end studio monitors, an interface that can handle complex calibration setups, and a room that is extremely well behaved acoustically. The cost of cabling and speaker mounting alone can exceed what many of us would want to spend on an entire stereo monitoring setup.

This being the case, it’s not surprising that there are many products intended to let you mix immersive audio on headphones. In the pages of SOS, for example, we’ve already covered Embody’s Immerse Virtual Studio Signature Edition, Genelec’s AuralID and APL’s Virtuoso (as well as packages like Slate VSX and Acustica Sienna that do the same in stereo). The latest company to enter the fray are Neumann, with something they call Reference Immersive Monitoring Environment, or RIME for short.

RIMEs Of Goodbye

Neumann have long been part of the Sennheiser group, and one of their stablemates until recently was a company called Dear Reality, who were responsible for one of the earliest attempts to translate immersive monitoring onto headphones, with a product called dearVR Monitor. Sennheiser closed down Dear Reality earlier this year, and several of their engineers were hired by Neumann to assist with RIME development. However, RIME is a wholly new product, which is not based on the dearVR Monitor code, and which actually embodies a different design philosophy.

Products such as dearVR Monitor and AuralID use mathematical methods such as ray‑tracing to model the way in which sound coming from multiple point sources impinges on the ears. Some, like APL Virtuoso, add a modelled virtual room environment, but what you’re hearing on your headphones is always an idealised setup rather than one drawn from real life. By contrast, products like Immerse Virtual Studio and Sienna attempt to recreate the experience of being in a specific, real‑world immersive mixing room. This is achieved by capturing impulse responses at the listening position.

Rather than travel the world measuring other people’s mix spaces, Neumann have chosen to build their own immersive mixing environment and measure that.

It’s this second approach that Neumann have taken with RIME — except that, rather than travel the world measuring other people’s mix spaces, they’ve chosen to build their own immersive mixing environment and measure that. This space, naturally, uses Neumann’s own loudspeakers and MA‑1 calibration system throughout, whilst the impulses were recorded using Neumann’s classic KU100 ‘Fritz’ dummy head.

In principle, both approaches have their own benefits. The fully virtual approach pioneered by Genelec and Dear Reality is infinitely flexible, with endless freedom to change the number and position of sources within the monitoring environment. This is not a trivial advantage, especially in a world where different immersive formats specify different speaker layouts; there are not many real‑world studios that can fully cater to multiple immersive playback specifications. On the other hand, the impulse response approach used in RIME should be able to offer a level of ‘being there’ realism that perhaps isn’t possible with a completely virtualised environment.

Turning Heads

An important factor in any headphone‑based 3D monitoring system is recreating the ways in which our outer ear, head and torso shape the sound arriving at our eardrums. The coloration introduced by these structures is critical to our ability to localise sound coming from different directions, but doesn’t occur naturally with headphone listening, so needs to be introduced somewhere along the way. It can either be added on playback using a complex set of filters called a head‑related transfer function (HRTF) or, as in Neumann’s case, baked into the initial impulse response recordings by capturing them using a dummy head.

Either way, the problem is that no two people have the same ears or bodies. An HRTF or dummy head response that works well for you might not work so well for me, and vice versa. With this in mind, companies such as Genelec and Embody have developed systems for deriving personalised HRTFs from photos or videos, whilst others are content to use generic measurements in the assumption that these will be close enough for most people. Neumann’s approach doesn’t leave open the possibility of using different HRTFs, but even so, RIME does allow a certain amount of personalisation, as we’ll see.

Another factor that can influence the realism of the results is, of course, the headphones themselves. All of this modelling and/or sampling assumes a completely neutral playback system, but most headphones deviate from the flat in some ways. Again, there are various options open to developers. They can leave it up to the user to linearise their headphones using a separate product such as Sonarworks SoundID Reference. They can incorporate corrective equalisation themselves, as for example APL and Embody have done. Or they can restrict the software to working only with their own headphones, giving them complete end‑to‑end control over the sound. Genelec have been moving in this direction, with AuralID now integrated into their overarching UNIO framework, and Neumann have taken the same approach with RIME, which is designed only to work with their NDH 20 and NDH 30 headphone models. I tested it with the latter.

RIME Time

RIME is available as a plug‑in for macOS and Windows in all the major native formats; there’s no standalone ‘systemwide’ version. It’s authorised using a serial number and, on installation, you have the choice to install the impulse responses at various different sample rates. If you’re never likely to work at 176.4 or 192 kHz, you can save yourself a few hundred megabytes by leaving those IRs out. In an Atmos project, you’d typically place RIME directly after the Dolby Atmos Renderer plug‑in, with the Renderer set to output to 7.1.4 rather than binaural. The room that RIME recreates is a 7.1.4 setup, but there’s freedom to solo or mute different speakers, so you can scale this down or use RIME as a stereo virtual monitoring environment if you wish.

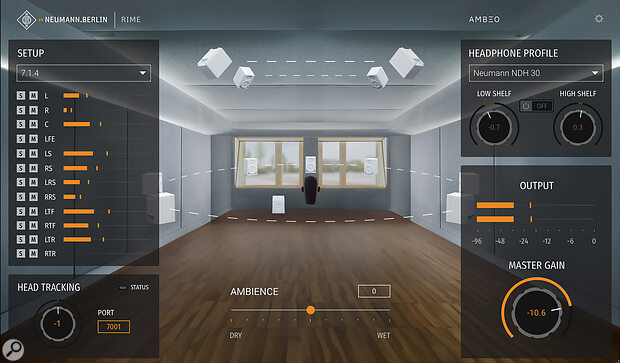

The alternative view shows each speaker in its correct position.

The alternative view shows each speaker in its correct position.

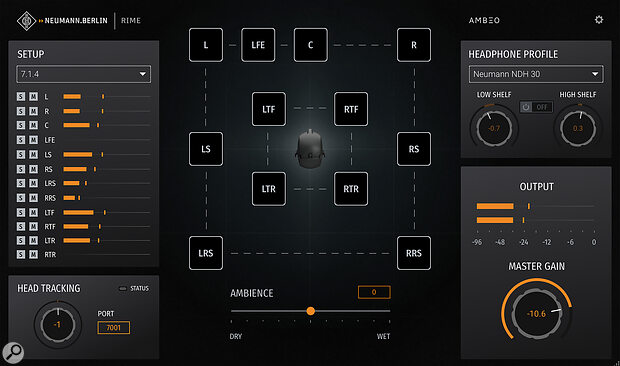

Compared with some virtualisation plug‑ins, the control setup is mercifully simple. The centre area can display either a stylised visual representation of Neumann’s reference immersive mix room, with the speakers superimposed in white, or a grid‑like view somewhat akin to Genelec’s GLM speaker matrix. In the latter view only, clicking on an individual speaker will solo it, whilst Control‑clicking will mute it. It’s not obvious why this couldn’t be made to work in both views, but that’s hardly a big deal. There is also an Ambience slider which is self‑explanatory.

To the right of this view, you get to choose which Neumann headphone model you’re using, and apply basic shelving EQ if required. The settings pane also conceals the option to boost the LFE channel by 10dB, which helps to compensate for the fact that you can’t ‘feel’ low‑frequency content in the same way when monitoring on headphones. The left‑hand side of the screen, meanwhile, lists each speaker individually, with tiny mute and solo buttons, and also contains controls for the optional head tracking. To get this to work automatically, you’ll need an OSC‑capable head tracking device, which I don’t have, but it’s possible to get some idea of how it sounds by manually adjusting the Head Tracking control as you rotate your head (by up to 180 degrees, for any owls who are into immersive audio).

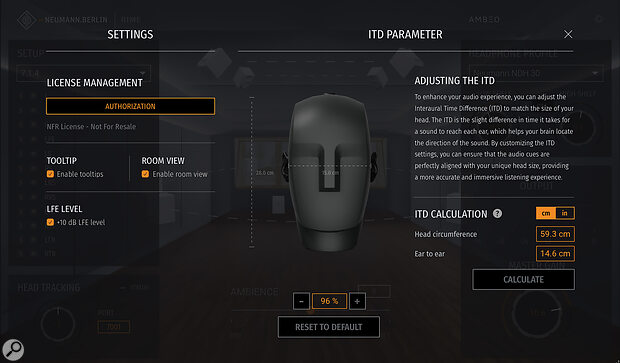

Perhaps the most interesting and unusual parameters are found in the Settings pane, which is accessed through the cogwheel icon. Although RIME cannot work with personalised HRTFs, it does give you the option to adjust the Interaural Time Difference based on simple measurements of your own head. These are easily carried out if you have a tape measure to hand. My own head turns out to be slightly smaller than the default, and reducing the ITD to 96 percent made a noticeable difference to the precision of localisation within RIME.

The Settings pane allows the Interaural Time Difference to be adjusted based on simple measurements of the user’s head.

The Settings pane allows the Interaural Time Difference to be adjusted based on simple measurements of the user’s head.

The Third Dimension

Having used quite a few virtualisation plug‑ins over the years, I’ve come to the conclusion that this is a valuable technology, but you need to have realistic expectations about what it can do. When we mix in a real studio on speakers, we are continually making small movements with our heads, but not simply rotating them in a fixed position. We tilt our heads from side to side, we move left and right, we lean forward and back, and when we hear something coming from behind us, we instinctively turn around. Head tracking can capture these motions, but few virtualisation plug‑ins around are sophisticated enough to model all of their audible effects.

The consequence, as I see it, is that although a plug‑in like RIME can deliver a sense of being in an acoustic space, it’s not exactly like being in the room that it attempts to recreate. Head tracking in this case is limited to horizontal rotation, which is a lot more effective than nothing at all, but not enough to make you forget you’re wearing headphones. And although the ITD adjustment does help to snap everything into focus, it doesn’t quite substitute for a full personalised HRTF. Localisation of static sources behind the listener really requires head tracking to be effective, and localisation of static sources above the listener is limited because the head tracking is only in the horizontal plane. But get those sources moving using the Atmos object panner, and you’ll be at least somewhat convinced they are flying around over your head.

In terms of useful application, then, I’d say RIME is quite similar to most rival products. It would be ambitious to expect to be able to do an immersive mix entirely on headphones, without ever referencing the results on a speaker‑based setup; but if you already have access to such a setup, especially one based around Neumann’s own speakers, RIME would be extremely useful for working on projects away from the studio, carrying out mix revisions, and so on. And I don’t mean that to sound underwhelming. The high cost of physical immersive monitoring setups means that many people don’t have full‑time or permanent access, and if you are a university student or part of a team in a busy post‑production suite, something like RIME could be the perfect bridge. It’s one of the most affordable products of its type, at least assuming you already have Neumann headphones, it’s easier to use than most, and it does pretty much everything you’re likely to need.

Pros

- Easy to set up and use.

- More affordable than most alternatives.

- Does a good job of virtualising a speaker‑based immersive mix room.

Cons

- Only compatible with Neumann headphones.

- Does not support personalised HRTFs.

Summary

RIME is another solid addition to Neumann’s increasingly comprehensive range of monitoring tools, helping to bridge the gap between headphone listening and speaker‑based immersive audio.

Information

$99.95