Soaring, anthemic descants and quicksilver runs are the meat and potatoes of old-school string arranging. But they may not be enough to save the day when disaster strikes…

In Part 3, I spoke about subtle string sonorities such as harmonics, dreamy cluster chords and 'div trems', the latter being string-player-speak for 'divisi tremolo' (a technique where half the players in a section play tremolo and the rest use a straight bowing). These delicate timbres can sound beautiful in a quiet musical setting, but when pitted against a rock band cranking out monster riffs, they fail to make any kind of impression. In order to cut through the sonic fog of distorted guitars, dense keyboard pads, stentorian vocals and thrashing drums, we need something a little less ethereal.

The old standby for string arrangers struggling to make their creations audible in a crowded musical environment is the high, soaring violins line, often written as a counterpoint to the vocal melody. This is such an established fixture in arrangements that you might be forgiven for thinking it was obligatory — I hear it all the time in the string demos that bands send me. In choral music, this type of high-pitched, decorative tune is called a 'descant', sometimes heard in church choirs when the sopranos sing a high counter-melody over the last verse of a hymn. It's a very satisfying musical device, and when applied to strings it can make good use of the violins' extreme high register.

Grey Skies

The beauty of descant lines is that they can be extremely simple: if a song has a quick, rhythmic vocal line, you can write a high counter-melody that uses few notes and moves quite slowly, thus creating a nice contrast. Such musical motifs can be a hook in their own right — you need to think melodically and try to compose simple, memorable phrases that enhance the song without stealing the lead vocal's thunder.

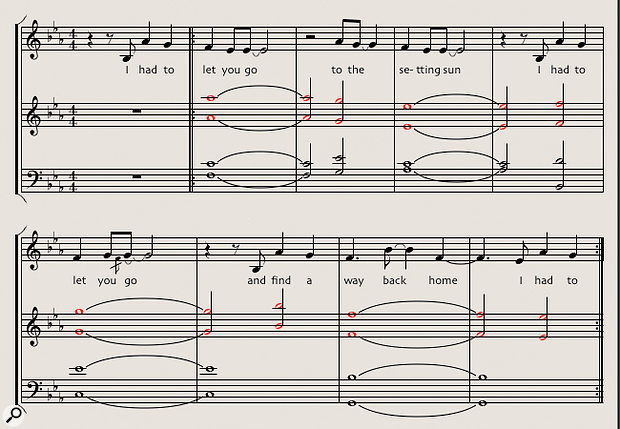

Diagram 1: Extract from the arrangement of 'Grey Skies' showing (from top down) the high countermelody (voiced in octaves), vocal line and keyboard chords.

Diagram 1: Extract from the arrangement of 'Grey Skies' showing (from top down) the high countermelody (voiced in octaves), vocal line and keyboard chords.

One of the simplest high string counter-melodies I wrote was for a song of mine called 'Grey Skies'. The backing track features a lot of programmed 16th-note percussion, above which floats a lyrical, balladic song. On the choruses, I added a high strings melody voiced in octaves, featuring long notes and minimal melodic movement — it's almost an exercise in how long you can get away with holding a note through the chord changes before moving to a new pitch!

I've reproduced the first few bars of the chorus of 'Grey Skies' in diagram 1. As you can see, the chords move at the rate of one per bar and the vocal line has a largely quarter-note rhythm, against which the high string line moves very slowly. Coupled with the fast, bubbling percussion and a half-time drum feel, these different rates of change combine into an agreeably ambiguous rhythmic stew. The simple counter-melody also introduces the subtle harmonic colouring of an F note over a Gbsus2 chord, a nice way of playing a (kind of) major seventh that avoids the sleazy, lounge-jazz connotations of that particular chord name.

To arrange this counter-melody for real players, you could simply assign the high octave to the first violins and the lower octave to the seconds, a classic orchestral timbre. Alternatively, if you needed some chordal support from the strings, you could divide the first violins to play the upper and lower octaves of the high melody, write chord pads for the second violins and violas, and bring in cellos and basses to reinforce the bass line — perhaps the kind of thing I've sketched out in diagram 2.

Diagram 2: A fleshed-out string arrangement of the 'Grey Skies' excerpt designed to support the high violins counter-melody in diagram 1. The three-note chords are played by divisi second violins (marked in blue) and violas, while the bass line is played by cellos and basses in octaves. Some chords contain tone intervals, a harmonic coloration favoured by your author that is often considered de trop in conventional pop/rock arrangements.

Diagram 2: A fleshed-out string arrangement of the 'Grey Skies' excerpt designed to support the high violins counter-melody in diagram 1. The three-note chords are played by divisi second violins (marked in blue) and violas, while the bass line is played by cellos and basses in octaves. Some chords contain tone intervals, a harmonic coloration favoured by your author that is often considered de trop in conventional pop/rock arrangements.

Untouchable

The UK band Anathema (for whom I've written a fair number of string arrangements) are no strangers to counter-melodies — many of their songs are constructed over repeated melodic motifs which play in counterpoint to the vocal lines. One such example is the song 'Untouchable'. This is split into two parts: the first builds into an intense, rocky anthem with distorted guitars and a heavy backbeat, while the second is a quiet ballad featuring a touching male/female vocal duet sung by Vincent Cavanagh and Lee Douglas.

The compositional basis for this song is a simple piano figure played by Danny Cavanagh, shown in diagram 3. The top notes of the chords (marked in red) pick out a simple, engaging melody. This is a good example of effective 'voice leading', a vital skill every composer and arranger should strive to master. I particularly like the way the final melodic movement from F to Eb transforms the harmonic make-up of the chord from a Gm7 to an 'Eb over G' (aka 'Eb first inversion').

Diagram 3: The piano part of Anathema's 'Untouchable Part 2' with its repeated melodic motif marked in red.

Diagram 3: The piano part of Anathema's 'Untouchable Part 2' with its repeated melodic motif marked in red.

My string arrangement for 'Untouchable Part 2' features the piano motif played in various registers: it starts out low and subdued on violas, before moving up an octave into the violin register. In the second chorus, it ascends again and is played in octaves by violins. Diagram 4 shows how the lead vocal part works in tandem with the violins' counter-melody; while the vocal is rhythmic and syncopated, the strings play straight, slow on-beat whole and half notes (or semibreves and minims, as we call them in the trade).

Diagram 4: The four-part string arrangement for the chorus of 'Untouchable Part 2', written for an instrumentation of first and second violins, violas and cellos. The slow movement of the violins counter-melody (marked in red) contrasts with the faster, more rhythmic vocal line.

Diagram 4: The four-part string arrangement for the chorus of 'Untouchable Part 2', written for an instrumentation of first and second violins, violas and cellos. The slow movement of the violins counter-melody (marked in red) contrasts with the faster, more rhythmic vocal line.

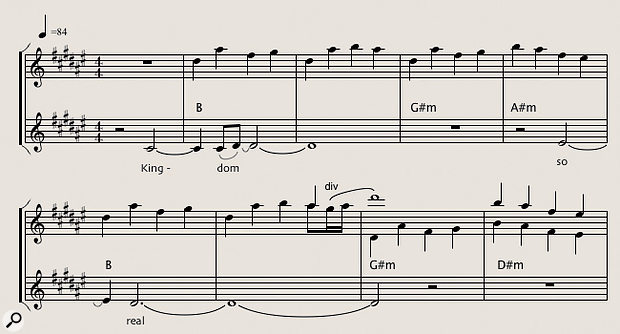

Another example of counter-melody occurs in Anathema's song 'Kingdom', but this time the roles are reversed: as you can see in diagram 5, the high strings line is far more rhythmically active than the sparse vocal line. Note the 'div' marking in bar 6, an instruction (as discussed previously) to the first violins to divide into two equal sections to handle the upper and lower part respectively. Without this instruction, a player might think he or she should play both notes simultaneously. Notating the note stems in opposite directions (as in the last bar) also confirms the section division.

As mentioned earlier, descant string writing is ubiquitous, and if nothing more adventurous is required, simply being able to write a high counter-melody might just be enough to get you hired as an arranger! Although I don't buy into the whole flag-waving bit, one of my favourite string descants happens in an arrangement of the hymn 'Jerusalem' I have on a BBC Last Night of the Proms CD. After the line 'bring me my arrows of desire' the violins take off in a soaring upward run culminating in a high D — it reduces me to tears every time. The power of music, eh?

Diagram 5: The repeated chorus of Anathema's 'Kingdom' — the sparse vocal moves at a slower rate than the insistent quarter-note violins part.

Diagram 5: The repeated chorus of Anathema's 'Kingdom' — the sparse vocal moves at a slower rate than the insistent quarter-note violins part.

Sprint Finish

Although it seems to have fallen out of favour in pop circles recently, the aforementioned fast ascending violins run is another staple of old-school string arranging. For that reason, virtually every strings sample library under the sun contains ascending and descending octave runs. Some, such as Peter Siedlaczek's Smart Violins and the more recent Orchestral Tools Orchestral String Runs, even specialise in the style. In the past, sample library manufacturers would record these runs in a choice of tempos in the hope that one might fit your track, but nowadays time-stretching can be used to force the runs to your song tempo.

An alternative to fiddling about trying to make these pre-recorded phrases fit your track is to play them yourself, although that naturally requires the ability to perform a scale on a keyboard. However, you don't have to play the run at a quick tempo; when sequencing a run, slowing the tempo down to half speed will take the strain out of the performance and ensure all the notes get played in the correct time span!

Keep in mind that although a conventional octave run can conveniently be played as eight 16th notes over two beats, you don't have to use eight notes in a run; a recent string arrangement of mine contained a fast ascending run of 15 notes, as shown in diagram 6. I didn't have this particular number of notes in mind when I composed it. The idea was to ascend quickly from Middle C to a high C over three beats, and the maths just worked out that way.

Diagram 6: A fast two-octave violins run played over the fourth, fifth and sixth beat of a 6/4 bar. Don't worry about the maths — the players will figure out how to squeeze all the notes in!

Diagram 6: A fast two-octave violins run played over the fourth, fifth and sixth beat of a 6/4 bar. Don't worry about the maths — the players will figure out how to squeeze all the notes in!

When confronted with such a run, string players don't perform complicated mental arithmetic to work out the precise length of each individual note; they simply treat the phrase as a whole and make sure it fits the allotted space in the bar. The result is an exciting 'whoosh', a bit like a fast harp glissando; small discrepancies within the section help to blur the rhythm and create the flowing quality that's unique to strings.

Diagram 7: Some typical examples of 16th-note 'classical' phrases, often used in arrangements to stoke up the excitement.

Diagram 7: Some typical examples of 16th-note 'classical' phrases, often used in arrangements to stoke up the excitement.

In film music, fast, 16th-note, classical-style string phrases are often employed to create excitement and propel the action. Such phrases tend to be simple and modular in construction: diagram 7 shows some examples, but it's more fun to invent your own! I went slightly bonkers with this approach in the Anathema song 'Sunset of Age'. Having been asked to give the piece an epic feel and further encouraged by its composer to "go apeshit”, I wrote the intense 16th-note passage you see in diagram 8 (below). It's played in unison octaves, with the last ascending run harmonised by the cellos a sixth down.

Diagram 8: Excerpt from the 'Sunset of Age' string arrangement. The upper line was played by first and second violins, supported an octave down by cellos. When the low part moves into the higher register (as in the second half of bar two and the first half of bar four), the violas take over from the cellos.

Diagram 8: Excerpt from the 'Sunset of Age' string arrangement. The upper line was played by first and second violins, supported an octave down by cellos. When the low part moves into the higher register (as in the second half of bar two and the first half of bar four), the violas take over from the cellos.

The Missing Parts

Enough of such musical triumphs. Disaster can strike when you're least expecting it, and no treatise of this type would be complete without a few string-arranging horror stories. I've been lucky enough to avoid the worst of these, although I did have a nasty moment when recording strings on a film score (sadly, the cinematic opus in question remains unreleased, hopefully not as a result of my contribution).

As is often the case in the film world, it was a rush job — there was barely time to write the cues, let alone check the copyist's parts before the session. On the day, I sat chewing my nails in the control room as players began to arrive and tune up. Then came the fateful moment: "OK guys, quiet please. Everyone ready? We're starting with the first cue, Pre-titles.” After some paper-rustling and muttering, one of the double-bass players said "Er, Dave — we haven't got any parts.”

These are not the words you want to hear when poised to record the first cue of your film soundtrack, and I had horrible visions of having to teach the bass players their parts by whistling them. Fortunately, it turned out that only one part was missing, and of course Sod's Law decreed it was for the cue we recorded first. Thankfully, the bassists were able to read their part from my score, after which we were back on track. Not a great way to start a session, though!

As disasters go, this pales into insignificance compared to the story of the arranger who set off for a strings session without realising a train strike was scheduled that day. The players showed up at the studio to find there were no parts, so amused themselves for the next two hours by doing the world's longest soundcheck and whipping out classical pieces they knew by heart. When the poor arranger finally showed up with the parts, two hours late, the string players saved the day by playing his scores absolutely brilliantly on the first take, thereby cramming three hours' work into the remaining hour left on the session clock.

What Key Are We In?

Some disasters are just plain funny. A friend of mine recounts an incident involving an internationally famous singer, known as much for his terminal indecision and brutal whimsicality (not to mention his unfeasibly tight trousers) as his vocal prowess. Shortly after an orchestral session, the artiste tells his long-suffering MD that he actually wants the song a semitone higher. Obviously it would have been better to decide that before recording the orchestra, but we're talking major-league superstar, I-can-have-whatever-I-want mentality here. The MD spends ages pitch-shifting the orchestra to match the newly requested key.

The album is finally completed about a year later. The artiste has an idea for its launch: invite a handful of important journalists to the studio it was recorded in, and have them sit in the live room wearing headphones, listening to a vocal-less mix of the album while the artiste sings a live vocal in front of the original orchestra (who are effectively miming). The whole event is being filmed for DVD at the same time.

Regrettably, when they come to play the key-changed piece, nobody has remembered to rewrite all the orchestra charts a semitone higher. The artiste and journalists can clearly hear the live orchestra playing a semitone lower than the recorded and pitch-shifted orchestra on tape. The unfortunate artiste tries to sing along to both. (Thankfully, no recordings exist.)

Moral for would-be arrangers: make sure the singer is comfortable with the key before you finalise a score.

The Bad Attitude

Although the modern breed of string session player combines musical excellence with a positive outlook, it wasn't always thus. In the late '80s, I was asked by my pal Jakko Jakszyk to write a string arrangement for an album track he was producing for a well-known artiste. Jakko takes up the story: "Being new to recording live strings, Dave and I needed help fixing the players. A friend of mine was from a classical music background, and his father (a respected section leader of one of the UK's larger orchestras) kindly offered to get together some of his colleagues and create a small section for us.

"I have to admit to being nervous on the day of the session. Here were half a dozen very experienced players with expensive vintage instruments and a long CV of recordings, concerts and TV appearances. People who were used to playing the most demanding music of the 20th century. And here we were — mere rock musicians making pop music. It was therefore confusing and somewhat alarming when the first couple of takes appeared to be riddled with mistakes. The timing wasn't great, and some of the tuning just plain unacceptable.

"We could hear that the cellist's low C string was a quarter-tone flat. When Dave asked the players to re-tune their instruments to an A=440 tuning tone, the cellist refused: 'No — you see, we don't tune up like that.' 'Well, how do you tune up?' Dave asked. 'It would take too long to explain. But basically, I tune my open strings flat and then play them into pitch on the neck.' 'Then what happens when it comes to the open bottom C in bar 88?' This stumped him. 'Er — yes, you have a point there.'

"What made this worse was that one of the older musicians kept looking at his watch at regular intervals. That's when he wasn't scanning his broadsheet newspaper between takes. Prior to another attempt at an error-free take, this guy piped up with "According to union rules, we really should have had a tea break by now”. We took one. It certainly didn't improve anyone's timing or tuning. Some hours in, and we were frantically making notes in the control room about which sections sounded OK and which we still hadn't covered. Meanwhile, in the cramped live area, the atmosphere of undisguised contempt from a couple of the players hadn't eased.

"We were just about to launch into yet another take when the same grey-haired player stopped us during the count-in. 'I've just noticed' he said, tapping his watch, 'that this piece lasts six or seven minutes, so by the time this take is finished, we'll be into overtime.'

"I resisted the temptation to inform him that had they played the f***ing thing right in the first place they'd all have been on their way home some time ago, and we somehow managed to negotiate a degree of goodwill from the majority to finish a final take.

"We spent the next day or so editing takes, trying to tune bits and cover up errors with fake strings. As a result of this experience, I avoided using live strings until 13 years later, when I hooked up with a group of young players fixed by the cellist/vocalist Caroline Lavelle. They sat down and played my printed sheets with a great, helpful attitude, and were complimentary about what I'd written. Where my inexperience as an untrained, novice arranger made itself evident with a wrong note or lack of dynamic marking, they all just took a pencil to their part with a broad smile. It sounded fantastic. It left me with a changed view, a love for the new guard and a desire to do nothing else again, other than writing for real strings.”

In Conclusion

Although most pro orchestral sample-users will tell you otherwise, it's not absolutely essential to use a large template containing all the separate components of a string section (first violins, second violins, violas, and so on), unless, of course, you happen to specialise in creating orchestral scores. A simpler way to get started is to use the 'full strings' patches supplied in many orchestral string libraries: these contain the entire string family mapped across the keyboard according to range, with adjacent instruments blended so there's no obvious timbral break as you move from (say) the high cellos to the low violins register. Diagram 9: A quick way of faking a full orchestral string section is to use just two patches (violins and cellos), set them to the same MIDI channel and create a split point between them. Splitting these particular instruments at Middle C often works well.

Diagram 9: A quick way of faking a full orchestral string section is to use just two patches (violins and cellos), set them to the same MIDI channel and create a split point between them. Splitting these particular instruments at Middle C often works well.

I've found this type of instantly playable patch to be incredibly useful for composing and sketching. In fact, I've often used them to develop string arrangements to the point of near-completion. If your strings library has no full strings patches, you can create a workable facsimile using violins and cellos: if you set the two patches to the same MIDI channel and adjust their key ranges (as explained in the 'Creating A Split Point' box) to create a split point at Middle C (see diagram 9 above), you can use the setup as a virtual full-strings patch and think about violas and double basses later. When considering the basses, bear in mind that they often work best in their traditional role of doubling the cellos part an octave down.

The beauty of the string family is that its instruments are designed to blend together into a unified whole, so if you use your ears and a bit of common sense when it comes to working out your instrumentation, you shouldn't go too far wrong! If you're unsure of the numbers of players required to create a balanced ensemble sound, my first string arranging article in SOS June 2012 contained some pointers. A more exhaustive study appears in Lesson 1 of Gary Garritan's 'Principles of Orchestration by Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov' thread at the Northern Sounds forum www.northernsounds.com.

OK, that's it. Thanks for following my thoughts on the big topic of string arranging over the last four issues of SOS, and thanks also to my colleagues for their valuable input. I hope some of the musical and technical ideas we introduced will spur you on to create your own arrangements, whether they be sampled or the real thing! Either way, it's nice to reflect that in this brash electronic era, we're still enjoying the fabulous, rich, expressive and moving sound of strings, a beautiful timbre that has been with us for over 300 years.

- 'Grey Skies' (D. Stewart) is from the album The Big Idea (Special Edition) by Dave Stewart & Barbara Gaskin www.davebarb.demon.co.uk.

- 'Untouchable Part 2' (Daniel Cavanagh) is from the album Weather Systems by Anathema.

- 'Kingdom' and 'Sunset of Age' (both composed by Daniel Cavanagh) are from the album Falling Deeper by Anathema www.anathema.ws.

- Thanks to all of the composers for permission to use extracts.

Masterclass Tips: Adding Samples To Real Strings

- If you're adding samples to a real string section, bear in mind that you may encounter tuning issues that go beyond the occasional out-of-tune note from the real players. Smaller ensembles, by their nature, expose tuning issues that would tend to go unnoticed in a larger group. European orchestras generally tune up to a different reference pitch (A=443Hz is quite normal, as opposed to the A=440Hz used here in the UK, and in the US). I've also occasionally come across real strings that were recorded without any kind of backing track, and were therefore globally flat or sharp of concert pitch. Depending on the situation, you may find it preferable to retune the samples rather than trying to pitch-shift the real recordings, as the latter process can noticeably degrade the sound.

- Adding big strings to small strings is generally not a great idea. If you have a quartet or octet and then add 60 sampled strings behind them, you're going to end up with a slightly odd sound; this isn't how people listen to strings in the real world! I've found that adding solo instrument or smaller-section samples to larger real sections works well, as the smaller sound often features more musical detail.

- Plan your overdubs. It's quite common in smaller film sessions or recording sessions to save time and expense by working out which bits the samples can handle better. For example, if you've written a piece that calls for a lot of artificial harmonics, these work best in the real world when there's a substantial number of players. If you have a smaller section and want a lot of exposed clean harmonics, use samples instead — you're likely to get a better result.

- If you have a passage that you know will be tricky — for example, relentless, tiring ostinati parts played to a tight, quick click that need to be bang on the grid — you might want the samples to take over at that point. If that's the case, remember to grab a take from the players with that particular part 'tacet', so as to leave a space for the samples in the mix.

- Layering sampled and real performances is not as straightforward as you might think. I've been asked a few times to layer sampled strings over the real thing and it can work pretty well, although there's a danger of it ending up sounding too massive and lacking in detail. I suppose it's the musical equivalent of trying to fix a photo by doing tons of Photoshop work — it can actually end up looking worse! I usually think of this kind of layering as a last resort, and have never needed to do it on my own sessions. If I'm planning a sampled/real hybrid, I generally try and get to the point on the live date where the samples and the live recordings complement each other, rather than doubling the same parts — David William Hearn.

Technical Note: Creating A Split Point

It's actually quite easy to set a split point between two patches, but some sample player programs make a bit of a meal of it. The procedure is simply a matter of adjusting the patches' key ranges. To do this in Kontakt, click on the small spanner icon (or cog icon, if you use Kontakt Player) in the top-left corner of the instrument window, select 'Instrument Options', and adjust the lower and upper notes in the 'Key Range' boxes.

In EastWest's Play sample player, this function is buried under Main Menu/Current Instrument/Advanced Properties, but the up side is that coloured keys on Play's GUI keyboard will show the new playing zone you've created. Best Service's Engine player and the Vienna Ensemble host (free when you purchase a VSL library) both conveniently display key-range settings on the instrument GUI, but the Vienna Instrument and Garritan Aria players appear to lack the facility altogether.

Adjusting key ranges is not the same thing as remapping the samples, since all you're doing is limiting the playable keyboard zone of an instrument, in order to squeeze another one in beside it. The only difficulty I occasionally experience is precisely identifying the crossover point: instrument makers have created confusion by failing to agree on whether Middle C should be called C3 or C4, but whatever the system, the note number always increments by one when you move up a semitone from B to C!