Bruce Springsteen’s latest album was an international hit last year, but the console it was mixed on was made a quarter of a century ago. Mixing legend Bob Clearmountain was at the controls.

“A note to your readers: you figure it out! That’s how I learned. Nobody told me what delays or reverbs to use. I would listen to records, and I’d try to work out what they had done, and then I’d try to recreate that, and come up with my own thing. The great part of mixing is figuring out for yourself what works for you, and for the music and the song and the lyrics, and what doesn’t. Asking me exactly how I did something is pointless. It really is. I know it is your job to report on this stuff, but dude, it doesn’t work this way.

“I learned by doing things,” Bob Clearmountain continues. “When I started at Media Sound in the ’70s in New York we mostly did jingles, and a lot of the time I was not watching somebody else, but I had to work out what to do myself. So if you’re sitting behind a computer, just try stuff. You can do anything you want. But forget about the presets. Presets are for dopey people. With any piece of gear, play with it and listen and learn all the things it can do.”

For the legendary Bob Clearmountain, listening is everything, and he prides himself in doing almost everything by ear, and being creative. It shows in many of his working methods, for example the fact that he still mixes on a console, at a time when the vast majority of his colleagues have gone in the box.

For the legendary Bob Clearmountain, listening is everything, and he prides himself in doing almost everything by ear, and being creative. It shows in many of his working methods, for example the fact that he still mixes on a console, at a time when the vast majority of his colleagues have gone in the box.

“Mixing in the box is like torture to me. I don’t understand how people can do that and remain sane. Working with little pop‑up menus and windows and so on is just not enjoyable to me. But when I’m mixing at my SSL, it’s so much fun, it feels like I’m having a day off! I love the process of mixing on a desk, and the sound also is a big part of that, of course. But most of all, it forces me to trust my ears, rather than my eyes. It’s about audio. It’s not a visual medium! A few years ago at an AES trade show someone demonstrated some edits in Logic, and then said, ‘Let’s hear what that looks like.’ I started laughing immediately. I thought it was a hysterical thing to say!

“DAWs have many advantages. It’s easy, for example, to align several bass drums in Pro Tools. We used to do that on tape: we’d fly stuff out to half‑inch tape, and then back in, and we’d use our ears to get them in time. It was more tedious and we couldn’t be as precise, but it worked. I don’t use Melodyne or Auto‑Tune but tune vocals using the Waves SoundShifter plug‑in. It’s a manual pitch shifter, and I use it the same way I used the Eventide H3000. I just listen and dial it in. I also do this completely by ear. Some things may not be perfect, and that’s fine, because you don’t want to completely suck the life out of a voice. Today, the vocalists in country music in particular sound like machines. They all sound like the same person, with the soul sucked out.”

Star Mixer

Bob Clearmountain inarguably knows a thing or two about mixing records that have soul and life, and about enhancing these qualities rather than stifling them. It was one of the main reasons he managed to become, in the early ’80s, the world’s first star mixer. The unbelievable amount of classic records Clearmountain has worked on over the decades says it all. They include records by the Rolling Stones, Hall & Oates, Paul McCartney, the Who, David Bowie, Chic, Bryan Adams, Roxy Music, Bruce Springsteen, INXS, Toto, Bon Jovi, Simple Minds, Sheryl Crow, Crowded House, Bryan Ferry, and many more.

Bob Clearmountain in the control room at his Mix This! studio.

Bob Clearmountain in the control room at his Mix This! studio.

Clearly, Clearmountain’s biggest achievements were, and continue to be, in the rock arena. And so one wonders how he survives in the current music world, which is dominated by genres like pop, trap, hip‑hop/R&B, that are all intrinsically linked to DAW‑based working methods, with vocals and programmed music perfectly pitched and timed, instant recalls, and tracks that are compressed and limited for maximum loudness.

Clearmountain stays well away from this particular musical maelstrom, and many of the associated working methods. He nonetheless remains not only the most celebrated mixer of all time, but also relevant in 2020, as was illustrated by his mix of Bruce Springsteen’s latest studio album, Letter To You, which went to number 2 in the US and number 1 in the UK, and in a dozen or more other countries. As Clearmountain‑mixed music for the umpteenth time tops charts around the world, it’s worth finding out how he works today, and to what extent he’s adapted to the latest technology.

“I was one of the first to use Pro Tools, in 1991,” comments Clearmountain, “though I’m still not very good at working with it. I must admit, as much as some people get mad at the guys at Pro Tools, this program is really good. They have come up with some amazing stuff. If you don’t mind the torture of working purely in Pro Tools, you can do great things. Especially helpful for me is the ability it gives you to fix small things. I do volume automation on my desk, but I’ll go into Pro Tools to correct a small detail, like a consonant that jumps too loud or that I’m not hearing. Clip Gain is great for fixing things like that, and you can also use Clip Effects to add a filter or EQ for a brief moment.

“I use some plug‑ins, mainly Altiverb, the Apogee ones, the FabFilter EQ, and iZotope to fix stuff, but for the most part I use Pro Tools still as a tape recorder. In the old days, when we were working with 16‑ or 24‑track tape, the drums were essentially four tracks: bass drum, snare and the entire kit in stereo. All balancing was done while recording, and quickly because you didn’t want to keep the band waiting. Now you can have everything separate, including ambient tracks, also for guitars or vocals, which is great when doing surround mixes. You can have endless tracks, and I love the control that gives you in the mix.

“I will for that reason not mix from stems. I’m not interested in that. Once in a while there will be something like a massive backing vocal arrangement or massive strings, and I will ask them to just send me a couple of stems of that. But I recently received a session for which they had stemmed the orchestra, and I asked them for the original orchestra tracks, which added up to 600 tracks! But I found it easier to work with that than with the stems, again, because I like the control.”

Control Room

The above lists most of Clearmountain’s concessions to the modern era. He’s also gone as far as digitising his analogue effects approach in an Apogee plug‑in called Clearmountain’s Domain (about which more below). For the rest his Mix This! studio, located in his home in Los Angeles, continues to look and function like it did when he built it back in 1994, centred around his SSL and tons of outboard. Before diving into the details of his mix of Springsteen’s Letter To You, Clearmountain elaborated on his tools of the trade, and what they mean to him today.

Bob Clearmountain still mixes through his SSL 4000 series console, and makes extensive use of its antiquated yet powerful automation computer (the green/black screen, top left).

Bob Clearmountain still mixes through his SSL 4000 series console, and makes extensive use of its antiquated yet powerful automation computer (the green/black screen, top left).

“My SSL is from 1994, and one of the last they made. It’s a 72‑input, 4000+ desk, which has the Bluestone mod, and I later added my own mods, many to do with surround mixing. Surround mixing is a big thing for me. I have done a surround mix for every stereo mix for the last 15 or more years. Sadly, surround isn’t particularly important for modern music anymore, so 99 percent of my surround mixes have never been heard.

“My main monitors are the Dynaudio BM15A, which I use for 5.1 as well as stereo, and they’re great. I had Yamaha NS10s for a long time, but then Apogee and I were thinking of doing our own speakers based on a newer Yamaha design, which were going to be called Clearmountain something or other. In the process Yamaha lent us these MSP7 speakers, and I ended up really liking them, so I’ve since been using them instead of the NS10s. The MSP7s are like the NS10s, but with a smoother top end and the bottom end goes down a bit further, and they’re self‑powered. But they stopped making them, and we never got round to making the Clearmountain speakers!

“I have two Pro Tools rigs at Mix This! One is my multitrack rig, which runs on the last 12‑core tower Apple made, also known as the ‘cheese grater’. It connects via three Apogee Symphony I/O’s to my SSL. My print rig is a ‘trashcan’ Mac Pro, and has one Symphony 16‑in, 16‑out I/O. My print rig is always at 96lHz. Both rigs are locked together with the Apogee Big Ben supplying the multitrack with word clock, and the print rig with video sync.”

Outboard Equipment

Bob's core outboard processors.

Bob's core outboard processors.

Clearmountain’s outboard includes a lot of classic gear, and he highlights some of his favourites. “I have five Pultec EQP‑1A3 tube EQs, which I love. Two of them are the new reissues, which are identical to the old ones. Apogee did a plug‑in emulation of the Pultec, and I cannot tell the difference between the plug‑in and the outboard, which kind of annoyed me, because I spent a lot of money on these hardware things [laughs]. In addition, the Avalon AD2055 EQ has a really nice, warm bottom end, and my BSS DPR‑901 dynamic EQ is great for problem vocals.

“As for compressors, I have four Empirical Labs Distressors, which is probably the best‑ever modern compressor. They do something wonderful to acoustic guitars, bringing them upfront and making them vibrant and useful. I also have three UREI 1178s, which are the stereo version of the 1176. They are fantastic, and I often use them on vocals and drums. My Neve 33609 stereo compressor is mostly used on bass. I have an SSL compressor which is the same as I have in the desk, and that I tend to use on piano.

“I also have four LA‑3A compressors, which are great. The Apogee Opto‑3A compressor plug‑in is almost identical, so a lot of the time I will simply pop in a bunch of those on backing vocals. I also have a bunch of old dbx 901 de‑essers. Other effects units include a couple of Yamaha PCM70s, a Yamaha SPX990, a bunch of Eventides like the H3000 and H3500, though most of them don’t work. I still really like the Eventide Ultra Harmoniser DSP4000. I also have an SPL Transient Designer, which I practically never use, and the old MXR flanger/doubler, which is really great.”

Clearmountain became famous for his elaborate effect chains, some of which he replicated in the Apogee Clearmountain’s Domain plug‑in, with a domain being, as Sam Inglis explains in his review of the plug‑in, “a blend of treated reverb, delay or ambience that gives each mix its own specific character.” (See www.soundonsound.com/reviews/apogee-clearmountains-domain.)

“Over the years I was always experimenting with different things with effects and I ended up with signal chains that used my SSL, delays, pitch‑shifters, our own convolution reverbs, and other things,” elaborates Clearmountain. “I always had my echo patches, and I would patch these into delays and reverbs and I’d modify them a bit for each project. It intrigued me, they were like fun puzzles, with me finding interesting ways of getting particular sounds. Clearmountain’s Domain is made up of these different experiments, which are easily customisable by the user. Most of my outboard digital delays have died now, so it was great to recreate them in the Domain, and I now use the plug‑in in most of my sessions. The presets in the plug‑in were an afterthought. Apogee asked me to do presets of effects similar to those on classic hits I mixed in the past, which I for the most part had to recreate by ear. So they’re not all that accurate, to be honest.”

Mixing in the box is like torture to me. I don’t understand how people can do that and remain sane.

Reset & Forget

Because of his motto ‘listen and be creative,’ Clearmountain doesn’t like presets or habitual mixing. It therefore does not come as a surprise that he wipes the slate clean at Mix This! every time he starts a new project. “Everything on the board gets normalised, just set to zero. There are a couple of patches that I usually start with, like there’ll be a parallel snare channel, with the parallel having one half of an 1178 and an EQP‑1A3, but that’s all. I also have sort of a template at the bottom of my Pro Tools sessions, with several aux effects tracks, many of which have my Domain plug‑in.

“People tend to send me Pro Tools sessions to mix. I ask for sessions without plug‑ins or bussing of any kind, or just a bunch of files. Sometimes it’s easier to create a session from files, rather than convert someone else’s Pro Tools session, and having to work out what I need to get rid of and what I want to keep. As I said earlier, I don’t mix from stems. Of course, I listen to the rough mix, to hear what they did and get the vibe and the feeling they’re going for. But I prefer to duplicate what they have done in my own way, especially with regards to delays and reverbs and so on.

“I prefer to start a mix with nothing, because I want to hear the original track sounds before I do anything. I will listen carefully before I add anything. So I’ll listen to everything with all the faders up, and then I’ll go into individual channels. I’ll solo each channel to get familiar with what’s there and what contribution each instrument makes and learn about the arrangement. Of course I’ll also check if here are any weird noises or rumbles that need taking out.

“The first few passes of the mix is more of a learning process. After that I usually start working on the vocals and guitars. To me the song is mainly about the vocals and if there are a bunch of guitars, I want to know how they balance out and what the arrangement is. Eventually I’ll get to the drums and the percussion, and how they relate to each other and the rest of the arrangement. I’ll be panning things throughout this process. Stereo and surround mean a lot to me with regards to how everything is arranged.

“Once I have a mix that sounds good with a basic balance, I’ll get into volume automation. Mixing with the SSL mix automation is by far the best way to mix. It’s a natural, wonderful way of mixing. They had listened to a lot of comments from mixers like Frank Filipetti and I over the years, and by the time of the last software update in 1995, they had really nailed it. It’s still on floppy disks! It’s a shame people don’t know about it, because it is so good, especially compared to any current DAW or digital mixer. You can grab anything at any time, and it remembers everything you do. I don’t understand how anyone gets a decent mix in Pro Tools or Logic or any DAW, because they all suck. Ironically, the ancient SSL mix automation is far ahead of any of these systems, and it’s fun to use.

“To give one example: you can’t playlist your mixes in any DAW. In the SSL you have an unlimited playlist of mixes, and you can edit between them, take the chorus from one mix and the middle eight from another, and so on. It’s so much better, it’s mind‑boggling. Compared to 1995, all these 2020 systems are just pathetic. I asked Avid why they don’t make it possible to playlist your mixes, and they said: ‘Do you know how much information that is?’ I said that all they really had to do is volume — in the SSL most of the rest of the mix is static. But they said, ‘it’s either all or nothing.’”

‘Letter To You’

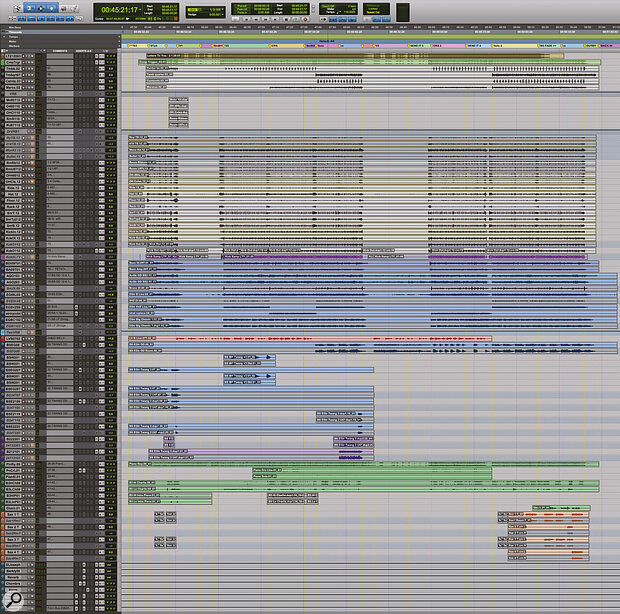

The session for the title track and first single off Springsteen’s 20th studio album, Letter To You, contains about 60 active audio tracks, and eight aux effect tracks at the bottom. A small number of audio tracks and three aux effect tracks in the session are de‑activated.

![]() letter-you-protools-session.jpg.zip

letter-you-protools-session.jpg.zip

From top to bottom the session contains a rough mix and a Comp Trigger track (explained below), drums and percussion in black, bass and guitars in blue, lead vocals in red, more guitars in blue and purple, piano and Hammond B3 in green, saxophones in orange, and the aforementioned aux effect tracks in blue. The aux effect tracks consist of four tracks with Altiverb (St Joseph, Berkley Street, Reverb and Chambers), a Harmonizer track, and three tracks with the Clearmountain’s Domain plug‑in.

The session for ‘Letter To You’. As well as the album version, the session also contains the mix used in the Letter To You documentary, with an uncompressed mix being used to trigger compression on the stems. Download the ZIP file for a larger view showing full details.

The session for ‘Letter To You’. As well as the album version, the session also contains the mix used in the Letter To You documentary, with an uncompressed mix being used to trigger compression on the stems. Download the ZIP file for a larger view showing full details.

“This session was weird,” explains Clearmountain, “because there’s also the Letter To You documentary, and some of the sessions were more for the film mix. So there’s a rough mix track at the top, and the Comp Trigger track underneath is an uncompressed stereo mix, which is there for making stems for the movie. We used that to trigger the SSL stereo bus compressor, so every stem gets the same compression.

“The greyed‑out plug‑ins and tracks in the session are all from the Pro Tools session I was sent. The first thing I do is get rid of the plug‑ins. I tell people: ‘If there’s a specific sound you want, like distorted guitars, then just print it that way.’ I will do EQ on the SSL, and the compression with my outboard, and many of the other effects with my aux tracks.

“The snare drum parallel here indeed has the UREI 1178 and an EQP‑1A3 — the latter is actually broken, but I like it. I boost some 5kHz, really broad, to add overall brightness, and I also push 100 cycles, just to warm it up a bit. The main snare track will just have EQ on the desk. I also often add a bass drum sample to give some more solidity. The purple track in the session is their bass drum sample. In general I will brighten overheads. They had pairs of rooms mics like Neumann U87s, Coles ribbons, and I would have listened to how they sounded, and balanced them and if necessary added some of my own reverb or ambience.

“The reverbs I use depend on the song. Ballads tend to have longer reverbs. Sometimes only using the room track that’s in the session works great. If I add reverbs, it’ll often be from Altiverb, like Berkeley Street (the original name of the Apogee Studio), or, very rarely, St Joseph Church, which is too big for drums, and better suited to choirs and strings. Occasionally I use Altiverb’s Castle de Haar. It works well on things you normally use a plate reverb on, but I think it sounds nicer than plate. It’s warmer sounding and not quite as splashy. The Chambers auxes are my live rooms in Mix This! They now are used as storage spaces, so I have to use the Altiverb versions.

“With the bass, many people record the DI and the amp, and the latter will be ever so slightly delayed because of the circuitry the sound is going through. So if necessary I’ll align them the waveforms so they’re perfectly in phase. This tightens up the bass sound. I usually push both bass channels through the Neve 33609 compressor and the AD2055 for a bit more warmth in the bottom end.

“I mentioned that I love using Distressors on acoustic guitars, so I also did that here. Many compressors sound like they fight the particular dynamics of many acoustic guitars, whereas Distressors don’t. I would also have added some reverb to the acoustic guitars. In general I try to use a combination of similar reverbs on many of the instruments and the vocals. I don’t like this thing where each instrument has its own specific reverb, and it sounds like they’re all in different places. When I hear a record like that, it really annoys me, because I wonder: ‘Where is this place?’ It doesn’t make sense to my brain.

“On electric guitars I will often use some slap delays from Domain 1, maybe 90ms on one side and 125ms on the other side, just to give it a bit of aliveness, and then mix some reverb in with that. On the Pro Tools inserts of some of the guitars and keyboards I use the FabFilter Pro‑Q 2 EQ, the Apogee compressor, and the Soundtoys Tremolator. I don’t really like to talk about exactly what I do in specific songs. It totally depends on the song. I prefer it to remain a mystery. Once again, listen, and then try things yourself!

Vocals & Mix Bus

“With regards to the vocals, I listen to them and try to get a feeling for what the song is about, and I then try to figure out what the narrative of the song is, what’s in the head of the singer or the main character in the story, and to put myself in that place. So I try to get the feeling, and I then try a bunch of different effects to see what works the best. Sometimes it’s nothing. The vocals in the Crowded House song ‘It’s Only Natural’ are completely dry, because, well, it’s only natural! With a dry vocal you feel really close to the singer, who is right in your face, and I love that. You can have a dry verse and then some space in the chorus to expand and create a contrast. With Bruce’s voice I tend to go for a little bit of slap delay and some ambience. I think I had the Berkeley Street reverb on him.”

And finally, while it’s commonplace for mixers these days to have extensive signal chains on the master bus, partly in the service of maximising loudness, it’s another area where Clearmountain just absolutely will not play ball. “I print my mix straight from the desk. At most I’ll have a little basic compression from the SSL desk compressor on the mix. I compress mixes of live tracks more, because it adds to the excitement. I get within a couple of dB of going over, because you want to use as many bits as possible, but that’s it.

“I don’t go along with the whole loudness thing at all. Everything should have a place in the mix, but your overall mix doesn’t have to be super‑loud, because mastering and all the streaming services deal with that. My theory is that the whole loudness thing came about because at A&R meetings each A&R person wanted the tracks they brought in to be as loud as possible compared to all the other stuff. So they’d have an engineer send a final mix through a Waves L2 or something, and boost the level beyond comprehension. But it sounds like crap. It’s distorted and you lose all dynamics. I enjoy dynamics in a record. I don’t care about things being very loud. I want my mixes to sound like music!”

A Star Is Born

It’s almost a cliché to point out that Bob Clearmountain pioneered the role of the star mixer, and thereby paved the way for the likes of Andy Wallace, Chris Lord‑Alge and Serban Ghenea. But how did he actually get into that position? Certainly taking on the last name Clearmountain (his actual name is Italian) was a masterstroke of branding. But for the rest, did he devise a masterplan, or did it all happen by accident?

“I don’t really know how it happened,” laughs Clearmountain. “It was weird, because I did not deliberately try to get in that position at all. I realised very early on that mixing was my favourite part of working in the studio. I was producing at the time, which was the early ’80s, and I produced maybe three records a year or something like that, and I mixed nine or 10 records a year. But I hated producing, actually, and I did not think that I was all that good at it.

“To me mixing was far more enjoyable, and more and more people were asking me to mix, even while I was still on staff at The Power Station in New York. My manager said: ‘Maybe you should think about going independent, and I can get you a point, for mixing.’ Nobody had ever asked for a point for mixing before. Even band members very often did not get points. My manager was a brilliant guy called Dan Crewe, and I thought that what he suggested was crazy, but sure enough people started paying me points! This was around 1983‑84.”

No Repeats

One pivotal record in Clearmountain’s oeuvre that really made his name as a mixer was Roxy Music’s 1982 album Avalon, a brilliant‑sounding piece of work, full of sumptuous delays and reverbs. “People have talked about that record more than about anything else I have done,” says Clearmountain, “calling it some sort of breakthrough. It was indeed an amazing record. I’d love to take full credit, but I can’t. So much of it was due to the band, the incredible arrangements, and Rhett Davies, the producer. The wonderful arrangements really suited my way of working, so those mixes were quick and not difficult. They took four hours each, and I did two of them a day.

“I guess I was experimenting in the direction of working extensively with delays and reverbs and so on. But also, it suited many of the projects I was working on at the time. In that context, I have an interesting story about the Avalon album. After I finished it, people were just so buzzed about how nice it sounded — big and wide and luxurious, and so on.

"The next project I mixed was an album for the Australian band the Divinyls, called Desperate [1983]. I kept the approach of Avalon while mixing their album, and it soon became clear that the guys were not happy. After mixing two songs they pulled me aside and said: ‘Listen, you have to understand, we are not Roxy Music. We are not big, wide and hi‑fi, we are like a little nasty gritty spiky ball, an irritating punk band, so what you are doing isn’t working.’ I had to start all over. It’s often so good to learn from your mistakes, which would be great advice for a certain soon‑to‑be‑ex‑president. You cannot take your approach on one project and apply it to the next project. Each artist’s music is unique.”

Total Recall

![]() bob-clearmountain-track-sheets-large.zip

bob-clearmountain-track-sheets-large.zip

A selection of Bob Clearmountain’s outboard and console recall sheets.While many mixers would love to still be working on a desk, they don’t for the simple reason that they need the capacity for instant recall that a DAW provides. Clearmountain, however, says it’s not an issue for him.

A selection of Bob Clearmountain’s outboard and console recall sheets.While many mixers would love to still be working on a desk, they don’t for the simple reason that they need the capacity for instant recall that a DAW provides. Clearmountain, however, says it’s not an issue for him.

“Recalls are simple. Years ago I came out with this thing called Session Tools, that Apogee used to sell, which includes templates for invoicing and work orders, labels for tapes and CDs, and so on. I have since modified it pretty heavily for my own usage. We have a whole library of pictures of the outboard gear that appear in a FileMaker database layout. I print out the ones I need, and take a pencil and then mark the settings. It takes a few minutes, but it comes back perfectly.

"When possible, outboard gear is set to unity gain and most of the delays and ’verbs are in the box and saved with the session. It takes half‑an‑hour to set up the desk because you have to do it manually, but I think of that as a sort of Zen time of contemplation. The SSL computer remembers every knob, it comes up on a graphic display which is like graphics from the ’70s. It is one step above the Pong video game, but it works. I do recalls all the time. It’s even easier and quicker when I have the budget to pay my assistant to help, who works part‑time.”