FKA Twigs has worked with many big‑name producers, but it was experimental electronic artist Koreless who guided the making of her new hit album Eusexua.

“The fact that FKA Twigs’ last album went to number three in the UK is huge for me,” says Koreless, aka Lewis Roberts. “I tend to think that I make comparatively obscure electronic music, so it is nice to see it resonate with so many people. I don’t know if I also speak for Twigs, but we did not try to make a hit album. My feeling is that if you try to do that, it never works. The best thing you can do is just make the best music you can. And people love Twigs for being Twigs. Just doing what you think is right is always a good place to be.”

Eusexua is the third and most successful full‑length album in a career that has seen FKA Twigs, aka Tahliah Barnett, collaborating with artists like A$AP Rocky, Kanye West, Skrillex, Jorja Smith, Fred again.., The Weeknd, The 1975, and more. She has also co‑produced and co‑written with big names such as Emile Haynie, Paul Epworth, Jack Antonoff, Sounwave, Cirkut, Mike Dean and Benny Blanco, alongside more obscure producers. Eusexua continues this trend, involving both heavyweight pop producers like Jeff Bhasker, Stuart Price, Ojivolta and Stargate and relative unknowns such as AOD, Tic, Eartheater, Felix Joseph and Koreless.

Youth Policy

Koreless was Twigs’ closest collaborator during the making of the album, much of which consists of abstract, futuristic electronic soundscapes. Both artists are signed to the same label, Young (formerly Young Turks), who initially brought them together. “I was brought in to work on her second album, Magdalene [2019], initially just to do some vocal effects. We ended up getting on quite well and we made a few songs together for the album. From there on we have been working together more and more, including on her mixtape Caprisongs [2022]. For Eusexua we spent a lot of time together.”

Eusexua is FKA Twigs’ third full‑length album.Roberts and Twigs are the only constants in the credits for every track on Eusexua, with Roberts the featured artist and sole producer on one, ‘Drums Of Death’. “Much of Eusexua came into being through writing camps. We did one in Ibiza, one in Big Sur in California, and some smaller ones in London. We’d invite a really mixed bag of collaborators, from really established songwriters to other artists. For example, Twigs found this guy on Instagram called Matteo Santini [@xquisite_korpse] who is a wizard on the Elektron Machines. We might do a long improvised jam with him and Twigs and maybe someone else from a totally different world, and we might cut a few songs out of that. We’d just write all day, really fast. We were working really, really fast in general. During the songwriting camps there’d be five or six ideas a day, for a week or two.

Eusexua is FKA Twigs’ third full‑length album.Roberts and Twigs are the only constants in the credits for every track on Eusexua, with Roberts the featured artist and sole producer on one, ‘Drums Of Death’. “Much of Eusexua came into being through writing camps. We did one in Ibiza, one in Big Sur in California, and some smaller ones in London. We’d invite a really mixed bag of collaborators, from really established songwriters to other artists. For example, Twigs found this guy on Instagram called Matteo Santini [@xquisite_korpse] who is a wizard on the Elektron Machines. We might do a long improvised jam with him and Twigs and maybe someone else from a totally different world, and we might cut a few songs out of that. We’d just write all day, really fast. We were working really, really fast in general. During the songwriting camps there’d be five or six ideas a day, for a week or two.

“I think the concentrated writing camps were a new process for Twigs. It certainly was a new process for me. If we just sat down together to write songs it could have become quite predictable, and we wanted to get out of that. She always wants to stir the pot and try interesting things. Writing camps are a good way of doing that. There’s definitely something great about two people sitting down and writing a song, and Twigs and I have written many songs like that. But many of the best moments on Eusexua came from crazy songwriting camps, with three or four people having live jams.”

Country Life

Roberts develops his ideas from his studio in rural Wales. “I’m always working here in Wales, always making stuff, not always full songs, just elements that I’m cataloguing and reassembling later. I like working on just one small sound or loop quite intensely before starting to think about turning it into a song. Sometimes giving these small elements attention means that they need less support in the context of a full arrangement. I have a big folder of these small elements, to be used as starting points, either on my own records or with other people.

Lewis Roberts’ studio in rural Wales is set up to give him the feeling of listening on a gigantic pair of headphones.

Lewis Roberts’ studio in rural Wales is set up to give him the feeling of listening on a gigantic pair of headphones.

“My studio is in an annexe to the house. It’s a bit cobbled together, and it’s not the best room, to be honest. I like a really dead room, with monitors very close. I like to feel like I’m inside a pair of headphones. The walls are heavily treated acoustically, so it sounds good to me in here now. My monitors are ATC SCM 45As. I feel they’re too big for me, but they’re cool. I was getting a lot of weird ringy stuff bouncing off the back wall, so I tried placing them on window ledges and boxing them off into a makeshift pseudo‑soffit to stop the back wall reflections and that seems to work. They’re not properly soffit‑mounted for speaker boundary stuff, but the response is flatter and the stereo image is cleaner. They feel closer and more like a pair of headphones. I just got the Antelope Orion 32 as an interface. I like that it has lots of inputs, and it sounds good. I‘ve also recently got a few racks of outboard, an old AMX 1580 pitch‑shifter and delay that I absolutely love, the Alan Smart C2 compressor, some Thermionic Culture units, like the Rooster tube mic pre/EQ, and more.”

After trying his hands at Ableton in his early years, Roberts abandoned the DAW, only to reconnect with it later on. “I left Ableton for a while because it didn’t do a lot of the things I wanted it to do. I had a brief detour using Reaper, and then moved to Pro Tools. Ableton has rectified many of the issues I had with it in more recent updates, so I’m using it again. And I still use Pro Tools.

Koreless: I often have really long crazy effect chains, and smash everything together through compressors.

“I like writing in Ableton because of Max/MSP and the MIDI/MPE editor. I’m pretty fast with it now. I often have really long crazy effect chains, and smash everything together through compressors. My sessions can get really chaotic and busy, so I like to combine things in blocks, turn them into WAV files, and then transfer them to Pro Tools, where I chop them up. It’s mentally easier to deal with than thinking about a sound as consisting of hundreds of layers. In Pro Tools I try to think of it as just one layer, and treat it like a sample. I also like to record audio in Pro Tools, and finishing tracks in Pro Tools feels a little more professional. I seem to be able to make more sensible mix decisions in Pro Tools than in Ableton.”

Building Sounds

“In general, my process is to start with sounds,” says Roberts. “As soon as I have something interesting, I go from there. Once I have a sound I really like, and also often a sequence, the whole idea takes shape quite quickly. So I spend a lot of time programming. Too much time! I’m programming patches in different instruments, and in Max, but I found that I was spending so much time with Max that I’ve banned myself from using that at the moment!”

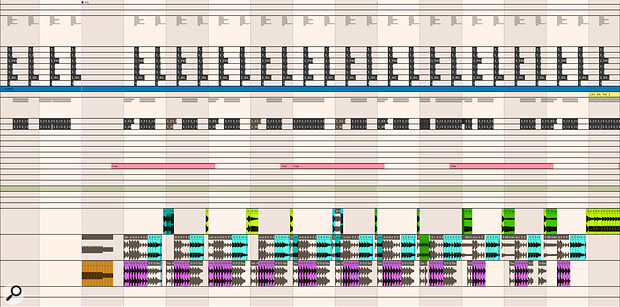

At the ideas stage, Lewis Roberts works mainly in Ableton Live. This screen shows the arrangement view for ‘Drums Of Death’.

At the ideas stage, Lewis Roberts works mainly in Ableton Live. This screen shows the arrangement view for ‘Drums Of Death’.

Roberts’ ideas were the foundation of three of the songs that appear on Eusexua: ‘Room Of Fools’, ‘Drums Of Death’ and ‘24hr Dog’. “When Twigs and I were finishing the album, we felt like we were missing something obnoxious and hard. I was flicking through a big folder of music that I’ve made, and came across ‘Drums Of Death’, and Twigs really liked it. I’d kind of forgotten about it really. We just cut it on the day. An artist called Tintin Freeman came in and helped write some of the poetry stuff that’s in there.

“My original demo was based on a sample of a vocal by G‑Dragon, who is a huge South Korean rapper. I sampled that randomly. I don’t know why. I guess the sonic quality of the voice was interesting. Normally when you’re cutting an audio file, you try and do a nice crossfade and make it nice and smooth. But with this, it was about trying to make all those pops and clicks as loud as possible. So I was cutting the waveforms at their highest peaks, and then adding only the slightest of crossfades, so that the vocal had a huge amount of transients to it. In context of that song, all of those pops and clicks sound like percussion. They all got smashed together through some saturation, which glued everything together. Chopping up the vocals at the highest points of the waveform is very ‘101 of things you shouldn’t do’!

“We kept some of that sample, and then we redid a lot of it with Twigs’ vocal. So we sat and re‑recorded every syllable 20 to 30 times just to get exactly the right diction. We did the chops on the grid in Ableton’s arrangement window, so we did not use a sampler or anything. For the rest, there are no synths in that demo, just a drum sample going through the Waves CLA 76, with 25dB of compression. It’s absolutely slammed, the needle barely moves out of its maximum position. That was it. It’s really simple. Just a lot of editing by hand.

“‘24hr Dog’ was another instrumental idea that I had that Twigs really liked. When I played it for her, she immediately started singing on top of it, and then we were like, ‘OK, we can use that.’ Twigs of course in general comes up with many of the vocal and lyric ideas. We have some posh mics to record her final vocals, but actually, we often use the Shure SM7B, because it adds quite a lot of low end to her voice, which is cool as her voice is quite high. The mic adds some nice depth, and it’s really good for writing, because you can use it in a room without it feeding back badly. We end up keeping a lot of the SM7B recordings.

“‘Room Of Fools’ took a long time. Twigs and I really changed that song a lot in the studio, adding all the pianos and so on. I had just the seed of the idea. We spent ages trying different things at her studio, which is very well equipped with ATCs and so on. It’s where we home in on stuff for long, long days. Marius [de Vries] added six bars of live orchestra at the end of the song. He was in Berlin recording something with a string section, and while we Facetimed he said, ‘OK, let’s just record it now.’ Marius also added the tablas.”

Writing Camps

As Roberts explained earlier, most of the tracks on Eusexua grew out of writing camps. “The album’s title track was a classic one. It was started in Ibiza. We were in the north of the island, at a yuppie hotel with an atmosphere similar to in White Lotus, the TV show. The hotel has a really well‑equipped studio in its basement, with big Quested monitors and so on.

“We brought in different people for a few days. Eartheater came to Ibiza to join us and played some amazing guitar chords and vocal ideas. We wrote ‘Eusexua’ together as a live jam, the result of loads of people throwing ideas down. That was a really difficult song to make. On the surface, it doesn’t sound like there’s too much going on, but there are many layers to it. Twigs and I were trying to balance two different worlds. We were looking for real toughness, but we still wanted it to be open and soft and quite ambient. We were looking for the drums to feel really aggressive and hard, but also like they were far away and throbbing and pulsing, and not an immediate threat. The drums needed to feel like something further, further away, imposing, but not too loud and harsh.

“‘Girl Feels Good’ was another one that started out as a live jam, during a writing camp, in London. AOD was playing the guitar chords, I had the acid‑like loop, and Ojivolta did the drums. This was all happening on different computers, going into our big Pro Tools rig, and then Twigs got the vocal down. Often we were still flicking through basic ideas on people’s computers, and then all of a sudden Twigs is signalling to have the mic. And then, before we had a chance to set up properly, we’re in it! We may not even have the sessions running properly yet, and there are already ideas flying around.

“Sometimes the lyrics would just be gobbledygook, and we’d have just a really rough idea of a song with some promise, but the feeling would be there. Sometimes we had something fully written, but the music was bad. There were many different things, and we’d mash them together and take a little bit from here and a little bit from there and put it all together into a larger whole. The writing camps were really fast and furious and chaotic, with ideas flowing everywhere. It was a bit crazy, but also very productive and fun!”

To keep track of the sessions, FKA Twigs and Roberts relied a lot on engineer Jonny Leslie. “He is also a great producer. He was there at the writing camps, often on the main computer, recording everything. Other producers would AirDrop stereo tracks to that computer. Sometimes we’d track into Pro Tools, sometimes into Ableton. Jonny was a big part of keeping track of everything and making sure things were well organised. This was quite a mammoth task at times.

“We tried to get about 80 percent of the song finished, and in between and after the songwriting camps, Twigs and I would come back to her studio, where we had the time and freedom to try out what worked and what didn’t. We really carefully put things together and rearranged them and changed the balance of things, and so on. She loves the Dave Smith Tempest drum machine. She’s really good at that, and she generates a lot of cool sounds on that that we added to the mix. So we’re just sitting and piecing everything together.

“We spent a long time at her studio chipping away at and rearranging the songs. Throughout this whole process, we’d have people come in to do something specific. If we knew someone good at a certain type of drums, they would come in to do that. Or they might work an arrangement thing, or do some additional processing. We worked a long time and had several people come and do different things. Sometimes we’d send a whole song to someone and they’d do a different version, and we’d take some bits of that and put it back into the previous version. We were trying everything.”

One advantage of living in the middle of nowhere is that there are no neighbours to annoy!

One advantage of living in the middle of nowhere is that there are no neighbours to annoy!

Searching

Trying everything also involved trips to LA to work with the aforementioned Marius de Vries, an eminence grise of the electronic pop world, who has worked with Björk, Madonna, Massive Attack, David Bowie and many more. “Twigs and I felt that there was something missing on the album, and we thought Marius might have the answer, and he did. He is responsible for many of the very beautiful organic live‑sounding parts on the record. He did some amazing string arrangements. We first met him in LA, and then he came to London for a bit, and later we went to LA again to meet him. He has a co‑production credit on ‘24hr Dog’ because he took many things out of the arrangement, which turned out to be genius. It made the song much better.

“At the end of this production process, Twigs and I would be rough mixing, and getting the sessions ready to send to the two mixers, Manny Marroquin and Jon Castelli. Both of the mixers did a really great job of making sense of quite dense productions. The arrangements are not always straightforward and often quite abstract, and they tidied everything up and made everything quite clear and so on.

“Working in a computer is not like recording on a multitrack. A lot of what I do is processing and stuff. I wasn’t thinking, ‘Oh, someone’s going to mix this at the end, so I can just leave it.’ I was trying to get it as close as possible. But you don’t want to do too much, because you want to leave some room for the mixers, especially with compression and EQ. I like to give them more options. They’re going to do a better job than me, with fresh ears and better skills. So I like to keep things alive and try not to control everything too much in the production process.”

When the question “What’s next?” is to put to Roberts, it turns out that he approaches his career with a similar attitude of not trying to control things too much. With a shrug of his shoulders, Roberts says, “I’m not even sure how my week is going to pan out! Doing the Twigs stuff was a surprise to me. So I’m open to more surprises!”

Digital Rules

As an electronic musician, Lewis Roberts’ work often involves synthesizers, but he has some unusual perspectives. “I tend to prefer early digital synths, because they have more interesting mechanics and they’re really flexible. The Nord Modular is one of my favourite synths, it’s from 1997. I love all the old Nord stuff. I also got a UDO Audio Super 6 recently, which is cool. And I really like the Roland SH‑101. I use mostly these synths at the moment.

“The old 101 is smooth and silky, and predictable and tidy, but many of the big old analogue synths that people love are not for me. They’re too unpredictable and boisterous. People love analogue synths because they have that bit of ‘oomph’, but you can get that back with digital synths if you just stick them through a nice preamp. I use the Thermionic Rooster for this. I run my digital synths through that, and I re‑amp soft synths through the Rooster as well. There’s something about the aesthetic of tidy, clean digital synths being driven gently afterwards that I really love. It’s very precise and feels like clockwork.

The left of the two equipment racks at Koreless’ studio houses his synths (top to bottom): Behringer Model D, Miditech MIDI interface, Oberheim Matrix 1000, Roland D‑550 and Nord Modular. The right‑hand rack contains processors and effects: Alesis Quadraverb reverb, Thermionic Culture Vulture valve processor, AMS DMX 15‑80 delay, Smart C2 and Aphex 661 compressors, Thermionic Rooster preamp and Roland SBF‑325 flanger.

The left of the two equipment racks at Koreless’ studio houses his synths (top to bottom): Behringer Model D, Miditech MIDI interface, Oberheim Matrix 1000, Roland D‑550 and Nord Modular. The right‑hand rack contains processors and effects: Alesis Quadraverb reverb, Thermionic Culture Vulture valve processor, AMS DMX 15‑80 delay, Smart C2 and Aphex 661 compressors, Thermionic Rooster preamp and Roland SBF‑325 flanger.

“The soft synths I have are not particularly interesting. The simpler the better, for me. With some of the soft synths I find there’s too much going on. I’ve also made some synths in Max/MSP that I really like. But instead of using synths, I like to work with bare waveforms a lot of the time. I’ll record just one long note and treat it in the Ableton arrangement view. I may move it and resample it and chop and/or reverse it. You can have better control over the envelope of notes and so on. The arrangement window is the most powerful tool of them all. Instead of having one synth, I like to put that one note on several different tracks that each have different effects. I think that’s more interesting.

“For effects I like spectral stuff, for example from the GRM plug‑ins. They make spectral effects that sound great. I use a collection of old plug‑ins that I’ve been gathering from the early 2000s, that still just about work on my new Mac, for example some of the Michael Norris stuff. He made some interesting plug‑ins. It concerns me that a lot of my favourite plug‑ins and gear are from a long time ago. Like my Nord Modular, which is software‑controlled. The software still just about works, but it’s a bit janky and I’m worried about the future.

“When I’m on a keyboard, I just noodle around. I’m not a particularly great keyboard player, and when I do use a keyboard I often gravitate towards the same chords and ideas. One of the reasons I like the Nord Modular is that I can program something semi‑random, and it will generate something I might not think of. I may start with a musical idea and use the Nord to generate sequences based on a chord or something, and then I’ll pick the best bits of that. I like to add elements of chaos!”