OneRepublic's route to the top has been tortuous, and their massive hit 'Stop & Stare' was actually recorded more than three years ago. Engineer and mixer Joe Zook recalls the sessions.

Ever since Decca Records turned down the Beatles in 1962, tales of record companies getting it dramatically wrong have been commonplace. Columbia dropping OneRepublic in 2005 was a case in point. At the time, the band had just completed an album, produced by Greg Wells and engineered and mixed by Joe Zook, but Columbia apparently decided that it wouldn't fly and so the band was shown the exit door.

A year later, OneRepublic became the most popular music act on MySpace, mostly because of 'Apologize', one of the songs from the as–yet–unreleased album. Timbaland subsequently signed them to his Mosley Music Group label and included a remix of 'Apologize' on his Shock Value album. Jimmy Iovine, head of Interscope, reckoned that OneRepublic's album contained five singles, and co–signed the group. Timbaland's remix of 'Apologize' was released in the Autumn of 2007 and promptly went multi–platinum, topping charts around the world.

Nothing to be sniffed at, of course. But following this enormous success, it was still possible to see OneRepublic as a one–hit wonder riding Timbaland's coat tails. Their second single, 'Stop & Stare' put paid to that perspective. It has been a top 10 hit in at least 12 countries, including the US and the UK. The album, Dreaming Out Loud, was hurriedly released to tie in with the single, and also rode the higher echelons of the charts in a great number of countries.

If this appears an amazingly steep rise to the top, it has to be pointed out that several of the people involved in the making of Dreaming Out Loud already enjoyed considerable pedigree. OneRepublic's singer, songwriter, pianist and guitarist, Ryan Tedder, had already worked as a producer, and collaborated with Timbaland during 2002–04. As of today he has written, and sometimes co–produced, hits for Jennifer Lopez, Natasha Bedingfield, Leona Lewis and many others. Moreover, Dreaming Out Loud was recorded at Rocket Carousel Studio in LA, the studio of producer and musician Greg Wells, who at the time had already worked with Rufus Wainwright, Hanson, Louise Goffin and Natasha Bedingfield, and who has since gone on to success with Mika.

Blueprint

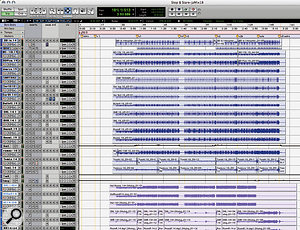

The Pro Tools Session for 'Stop & Stare'; drum tracks (below) were bounced to analogue tape at various different level settings to obtain tape compression.Another original participant in the Dreaming Out Loud sessions was Joe Zook, who has worked as an engineer and/or mixer for Tricky, Mika, The Hives, Modest Mouse, Pink, Lindsay Lohan, Courtney Love, Puffy Ami Yumi, Liz Phair, Remy Zero, Feeder, and many others. He recorded 12 songs during the mid–2005 sessions, and mixed nine of them, including 'Stop & Stare', in October of the same year, at his LA studio 4014 Mixing. After the band had been dropped and re–signed by Interscope/Mosley Music, another three songs were recorded by another engineer in late 2006 and mixed by Zook. Because three years have passed since the recording and mixing of 'Stop & Stare', Zook needed to extensively consult his recording notes and the Pro Tools Session file to remind himself what went on.

The Pro Tools Session for 'Stop & Stare'; drum tracks (below) were bounced to analogue tape at various different level settings to obtain tape compression.Another original participant in the Dreaming Out Loud sessions was Joe Zook, who has worked as an engineer and/or mixer for Tricky, Mika, The Hives, Modest Mouse, Pink, Lindsay Lohan, Courtney Love, Puffy Ami Yumi, Liz Phair, Remy Zero, Feeder, and many others. He recorded 12 songs during the mid–2005 sessions, and mixed nine of them, including 'Stop & Stare', in October of the same year, at his LA studio 4014 Mixing. After the band had been dropped and re–signed by Interscope/Mosley Music, another three songs were recorded by another engineer in late 2006 and mixed by Zook. Because three years have passed since the recording and mixing of 'Stop & Stare', Zook needed to extensively consult his recording notes and the Pro Tools Session file to remind himself what went on.

"We recorded from 11 in the morning until seven at night, Monday to Friday," Zook recalls, "and we would do a song in about three days. It was very much a spontaneous process, and we wanted to get the songs down quickly and roll with it and commit. There was no pre–production. With each song we'd listen to the demo, talk about what we wanted to do, record the song live with the whole band for a scratch version, and then we started tracking the drums. We usually did the bass the same day or first thing the next day, then we'd record the guitars and third day the vocals and a rough mix. Occasionally there was a fourth day for some extra things. And then we'd move to the next song.

"For instance, I recall that we started on 'Mercy' on a Monday, and by the following, that song and 'Stop & Stare' were finished and rough mixed. We revisited 'Stop & Stare' two weeks later to add the chorus background harmonies. 'Apologize' was the third song we cut, and it was revisited several times. The band were very young, almost all of them were 20–22 years, and they'd hardly had any studio experience, yet they were all very competent and played really well. It was their competency that allowed us to work like this.

"For this record everybody was trying to create a blueprint rather than follow one. We wanted originality. For me, the songwriting and Ryan's voice provided a lot of inspiration for how to create something unique and interesting. I would work off these when searching for new sounds and things that were exciting. We recorded to Pro Tools, often via Greg's vintage Neve 5114 desk. We used a lot of the equipment in Greg's studio, and I also brought down quite a bit of my own gear. Because we wanted to record things fast, I decided to put up lots of different microphones in addition to the normal drum microphones that were set up in Greg's studio, and would then mute the ones I didn't want while tracking. I probably had 18 to 20 drum microphones up, of which about 10 were standard."

Zook explains that he can't remember some of the drum and room mics that were used, saying "I'd never used many of these mics before. Greg had things set up, and he has good ears, so I trusted him. It was a matter of making what was there work. I recall that the room mics were Chinese MXL and the overheads were some kind of Gefell. The kick drum mics were an AKG D112 on the inside, going through an API 550 EQ and a Distressor compressor, and I had a Crown PZM mic in front. I also had an NS10 on the beater side, which was being pummelled and distorted, and went through a Universal Audio 2610 preamp and a Chandler EMI compressor. On the toms was, again, some Chinese mic, and there was probably a 57 or a Beta 57 on the snare. I also had a [Shure Green] Bullet mic on the snare, which I ran through a Deluxe Memory Man, a Ross flanger and a little Danelectro Nifty '50s amp, miked with an SM57. Bass drum, snare and overheads went through Brent Averill BAE 312a mic pres."

Dreams Of Fleetwood Mac

The vocal sound on 'Stop & Stare' was crafted using numerous delays and other effects.According to Joe Zook, the song 'Dreams' from Fleetwood Mac's Rumours album became a reference point for 'Stop & Stare', because "it has a similar quarter–note feel with hypnotic eighth–notes throughout the song". The engineer/mixer explains how this informed a number of choices that were made while recording and mixing. "When we recorded the drums, we ran into the problem that there was too much of a scene change between the verse and the chorus, when the drummer starts bashing the cymbals and this big drum room sound comes in. It wasn't working, and I remembered that on 'Dreams' the drums had been recorded without cymbals and the cymbals were overdubbed later on. So used that technique, and it worked great. It kept the mood throughout the song."

The vocal sound on 'Stop & Stare' was crafted using numerous delays and other effects.According to Joe Zook, the song 'Dreams' from Fleetwood Mac's Rumours album became a reference point for 'Stop & Stare', because "it has a similar quarter–note feel with hypnotic eighth–notes throughout the song". The engineer/mixer explains how this informed a number of choices that were made while recording and mixing. "When we recorded the drums, we ran into the problem that there was too much of a scene change between the verse and the chorus, when the drummer starts bashing the cymbals and this big drum room sound comes in. It wasn't working, and I remembered that on 'Dreams' the drums had been recorded without cymbals and the cymbals were overdubbed later on. So used that technique, and it worked great. It kept the mood throughout the song."

About half of the drum microphones went through the studio's Neve 5114 desk, while most of the remaining mics went through the BAE 312a preamps. An Alan Smart compressor and a GML EQ were used on the room mics. "We wanted it to sound like drums in a room, and it had to sound unique and somewhat dark in terms of mood, otherwise it would appear as if the drummer wasn't getting it. After recording the drums we moved on to the bass, which ended up being the scratch bass on almost all tracks. The bassist, Tim Myers, was really good and he nailed everything during these first scratch takes. I suspected that it would be possible to use the scratch takes and I had simply taken a DI out of the bass player's Ashdown amp head, going through a Neve V72 tube DI and preamp and an 1176 compressor. I recorded a lot of compression on some of the drum mics and on some other things when we knew we wanted to commit to that. The only exception was the vocals — we only compressed the vocal sound in the monitors, but didn't record it.

"The band have a unique approach to playing the guitar. Nobody is playing power chords and one of them is always playing high up the neck, single notes, with lots of delay. To give them a big guitar sound, the guitars needed lots of space around them. So I printed big stereo room mics. They were the same room mics as I'd used for the drums, in the same position, with the same signal chain, Alan Smart and GML EQ. I think the intro and the verse on 'Stop & Stare' were played via an open–backed Fender Deluxe in one room with two relatively close mics on it, a Royer 121 and a 57. In the other room there was a Marshall cabinet that was running through any one of the seven or eight heads that were in the control room, with effects committed to Pro Tools 90 percent of the time. Pedals were too numerous to mention, but 40–50 percent of them were delays using the Deluxe Memory Man. The guitar mic preamp was a Cranesong Flamingo, which went into an RCA BA25 compressor, from the '50s. It's all tubes, an old dinosaur kind of thing. Sometimes I was just running things through the RCA without adding an effect. In general the guitars were compressed very little, if at all.

"The acoustic guitar was recorded with my Dave Pearlman U47 mic. Dave is a few blocks away from me, where he rebuilds U47s. Before I bought the mic, I did a shoot-out with other U47s that I rented, and the Pearlman sounded incredible. The acoustic guitar mic also went into the Cranesong Flamingo and the RCA. I don't think I used any EQ. I simply moved the mic around until it sounded right. Recording acoustic instruments is a team sport. Nine times out of 10 a great acoustic sound happens when the player makes subtle adjustments, such as moving a couple of inches or changing picks. It's all in the hands of the player. I just try to stay out of the way of a great performance.

This composite photo shows some of the more obscure analogue gear at 4014 Mixing. Much of this was used on 'Stop & Stare', including the Collins 26U compressor (top), Cinema EQ (the dark unit with two large knobs about a third of the way down), Blonder Tongue B9b graphic EQ (centre), Gates Level Devil compressor (with the bright red light) and CBS Audimax II compressors (bottom). "The vocals were recorded with a Neumann U67. Ryan has one of these voices that engineers love. Whatever mic you put in front of him, he sounds like he is already EQ'ed. I wanted something soft and warm on him, and I didn't want him to start sounding thin when he went into the upper range. The U67 worked really well for that. Those mics need some EQ at their top end, in my opinion, but they always remain full in the mid–range, so they sound great when people sing high. We tried a few different preamps on him, and I was shocked to find that the Avalon 737 worked the best. I'm generally not a fan of the Avalon, but it was perfect on his voice. As boring as the Avalon compression is, it was very good at allowing an overall hotter level to be recorded without hurting the sound. I also added about 6dB around 32k, to give it more air. On the Avalon 737 the high–frequency shelf selections are 10kHz, 15kHz, 20kHz and 32kHz. The shelf is super–wide so when you grab 32k it extends pretty far down to audible frequencies. And that was it for recording. I didn't use plug–ins on the way in. Thirty tracks of drums were recorded, and 20 used after recording cymbals separately, the guitars were around 12 tracks, and there were six tracks of vocals.

This composite photo shows some of the more obscure analogue gear at 4014 Mixing. Much of this was used on 'Stop & Stare', including the Collins 26U compressor (top), Cinema EQ (the dark unit with two large knobs about a third of the way down), Blonder Tongue B9b graphic EQ (centre), Gates Level Devil compressor (with the bright red light) and CBS Audimax II compressors (bottom). "The vocals were recorded with a Neumann U67. Ryan has one of these voices that engineers love. Whatever mic you put in front of him, he sounds like he is already EQ'ed. I wanted something soft and warm on him, and I didn't want him to start sounding thin when he went into the upper range. The U67 worked really well for that. Those mics need some EQ at their top end, in my opinion, but they always remain full in the mid–range, so they sound great when people sing high. We tried a few different preamps on him, and I was shocked to find that the Avalon 737 worked the best. I'm generally not a fan of the Avalon, but it was perfect on his voice. As boring as the Avalon compression is, it was very good at allowing an overall hotter level to be recorded without hurting the sound. I also added about 6dB around 32k, to give it more air. On the Avalon 737 the high–frequency shelf selections are 10kHz, 15kHz, 20kHz and 32kHz. The shelf is super–wide so when you grab 32k it extends pretty far down to audible frequencies. And that was it for recording. I didn't use plug–ins on the way in. Thirty tracks of drums were recorded, and 20 used after recording cymbals separately, the guitars were around 12 tracks, and there were six tracks of vocals.

Joe Zook: "I find that mixing songs that I have also recorded can be tricky, because on some occasions I have tended to blow the track up and forgotten the song that's there. When I get tracks in that I haven't recorded I never have that problem, I usually get it right the first time. But with songs I've recorded I often go through the struggle of mixing them twice before I play them to anybody. I think it is because when you've recorded a track, you have preconceived notions about it. The challenge in the mix is not so much the sounds, because they usually are close to the way I want them, but more the levels.

"When I first mixed 'Stop & Stare', I made the drums and the bass massive. It became this huge grunge thing, and it just didn't sound unique or fresh. I'd started at five or six in the evening and I went home late at night being really proud of myself. But when I came back in the next morning, it was like, 'F**k, where did the song go?' There were all these great sounds, but it didn't feel right. The wall of jangly distorted guitars made it sound like from the '90s. I think I did email this mix to Greg just before I was about to take it all apart again, and he agreed, and said 'The rough mix is better.' I'd become too focused on all the unimportant aspect of the engineering, rather than the music itself.

"So I started again, and what I normally do in a mix is take my cue from the lead vocal, from what he or she is trying to do. Sometimes it even helps me to solo the vocal and listen to it from start to finish, without any effects. I just crank it up really loud, and I can hear how somebody is breathing, I can hear all the little noises that sometimes get lost in a track. I always get inspired by that, and I listen to whether different instruments want to support the emotion or juxtapose it. After putting up the vocal I bring in individual instruments and I ask myself what is helping the guy tell his story, and what is interacting and conversing with other tracks in the song. I like to find things that bounce off each other and converse. In this song it was the ambient verse guitars with the drum room sound, and eventually the vocal ambience. Once I'm clear on this, I pull everything back, and I start adding effects to the vocals. In the case of 'Stop & Stare' there were lots of them."

- Vocals: RCA BA25, Cinema EQ, Izotope Trash, Chandler EMI, Bomb Factory Cosmonaut Voice, Waves De–esser, Sound Toys Echoboy, Ross flanger, Vox AC30 amp and head, MicMix Master Spring

"I thought that Ryan's voice was really intense and emotional, and his consonants sounded really cool. So I put an RCA BA25 compressor on an insert on the vocal to bring that out. But when you are sending things really hot to the RCA, it starts to blow up and do really crazy things to the consonants, so I put a Cinema passive EQ before it. The Cinema was made in Burbank, probably in the '60s, and it has a high–frequency and a low–frequency knob, and you can get huge curves in the EQ. It has a beautiful tone and is wonderful for shaping vocals. I then added the Izotope Trash plug–in, to bring out some aggression. You can hear the Trash kick in in the choruses. This is called 'dist vocal.' If you put things on an insert you lose a generation, but since the effects are not subtle, who cares?

"On another vocal insert I had the Chandler EMI compressor, which I used more on the verses. I would then ride these two with the clean lead vocal. The lead vocal was actually doubled, and I had the Cosmonaut Voice plug–in on the double. The chorus double sounded too 'pop' untreated, like some other record. It didn't fit. So I really mangled the double vocal sound in the chorus with the Cosmonaut Voice plug-in to make it sound haunting. I don't know who makes this plug–in [it's part of the Bomb Factory collection now owned by Digidesign themselves — Ed], but it's great. It's a super tiny–sounding filter. It has pretty much only one sound, and a couple of seconds after the main sound ends it will either send out a walkie–talkie sound or a beep. So I always have to mute it immediately after using it to stop these noises coming through.

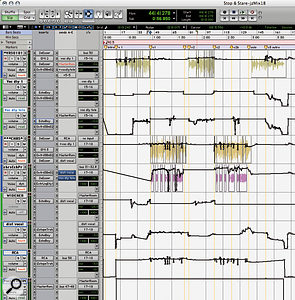

"Another plug–in I used was the Waves De–esser, because that is what I had at the time. I nearly rented the Dbx 902, but I got the Waves plug-in to work well enough. Today I use the Universal Audio De–esser in preference to any outboard de–esser. Then I also had three or four delays on the vocals. The way Ryan is singing is so cool, it kind of cried out for little voices in the background with a kind of twisted, distorted, warbling sound. So I played with some freaky–sounding delays. You can't see the whole delay story from the one screenshot, you'd need four: volume returns, volume sends, return mutes and send mutes.

"To try to summarise the delays, I had two sets of delays using Echoboy plug–ins with different sounds and different timings. One had heavy modulation, distortion, repeats and EQ to emphasise the singer's frustration, and the other was more subtle and had less regeneration and seemed to emphasise hope. I just rode them in and out where it felt right, just a couple of passes and then some fine–tuning here and there. The 'widener' and 'voc dly tele' tracks are both mislabelled. I started using a widener on one, and tried for a telephone effect on the other, but ended up using an Echoboy delay, and never renamed the tracks. "To get a heavier, more aggressive sound and a call-and-answer effect I also sent the vocal through a Ross flanger pedal, a Vox AC30 head and a 4x12 guitar cabinet, and then recorded it back in and cut it up and moved it in time. This wasn't as involved as it sounds, as I have it all set up in my studio through a routing matrix, so I can hear a variety of amps and heads and combinations of them in just a few minutes.

"To try to summarise the delays, I had two sets of delays using Echoboy plug–ins with different sounds and different timings. One had heavy modulation, distortion, repeats and EQ to emphasise the singer's frustration, and the other was more subtle and had less regeneration and seemed to emphasise hope. I just rode them in and out where it felt right, just a couple of passes and then some fine–tuning here and there. The 'widener' and 'voc dly tele' tracks are both mislabelled. I started using a widener on one, and tried for a telephone effect on the other, but ended up using an Echoboy delay, and never renamed the tracks. "To get a heavier, more aggressive sound and a call-and-answer effect I also sent the vocal through a Ross flanger pedal, a Vox AC30 head and a 4x12 guitar cabinet, and then recorded it back in and cut it up and moved it in time. This wasn't as involved as it sounds, as I have it all set up in my studio through a routing matrix, so I can hear a variety of amps and heads and combinations of them in just a few minutes.

"These days I use Echoboy and several other delays, because there are now a bunch of plug–in delays that are good. I love the Massey TD5, it's an analogue–sounding thing. And I often use the Universal Audio Roland RE201. Actually, UA has four delays that sound great and that I use all the time. I've also been using PSP's copy of the Lexicon PCM42. Plus, I often do a slap tape echo with my Studer A827 on an insert. Oh, and I use delay pedals, like the Deluxe Memory Man pedal. I must have 15 different delay options!

"Finally, the reverb on the lead vocal is from the MicMix Master Spring Room Reverb. It's big, beautiful, warm, dark and just nails the emotion. I used a lot of it on the whole album. It's a big long thing. You can't control the time, it just has a big chamber sound. As you can see from the screen shot [see page 136], I also did a lot of rides on the vocals, just to get everything to sit right. I kept tweaking until it sounded good. I'll go down to one syllable. Sometimes eight words will sound amazing and then all of a sudden there's a moment, usually at the end of a word, where there's too much breath sucking, or something else that needs to be ducked. I am always looking for the emotion, and sometimes it comes up easily, other times you need to tweak a lot and do a lot of rides to get the maximum expression. This was one of those cases."

- Drums: Valley People Dynamite, Empirical Labs Distressor

"As I said earlier, one of the biggest challenges of getting this song right was making the drums smaller. It's why we recorded the cymbals separately. When I did my first mix, the drums still were so huge, and the mood got lost. So I took all the faders down and took all the effects off everything, and stopped blowing it all up and then put the faders back up to where they were when I recorded them. This was much closer to what the song was supposed to be.

"The whole time I had been recording the drums I knew that it was missing analogue tape compression. So I went to Ocean Way, transferred the drums to an Ampex 124 and back to Pro Tools. The numbers at the end of the Pro Tools track titles are references to me recording to tape at different levels. So 18 was a little more than 14. You can see that I hit the rooms harder than the other elements, which had lower numbers, because I wanted to see how the transients in the room mics would respond to the tape. When I do this I'll sometimes cut between different levels. In some songs it may be better to have a more smashed–up sound in the chorus, for instance. But in 'Stop & Stare' the sounds go right through the whole song.

"The Bullet with which I had recorded the snare had lots of bleed on it, so during mixing I put a gate on it triggered from a snare sample. I also used the Valley People Dynamite and the Emperical Labs Distressor tube compressors on the snare and kick. I sent them out to a send and brought that back in. But for the most part the drums were recorded the way they sound on the record. If I needed more depth or another effect, I simply turned up one of the many microphones I'd used. There were other, tiny, cut–fader rides that I did, adding a few dB here or taking out a dB there. It was all about fader levels."

- Bass: Sansamp Classic, Ashdown amp, Gates Level Devil, Blonder Tongue EQ, Collins 26U

"Because I had recorded the bass via a DI, I wanted the acoustic sound of an amp in there, so during mixing I ran the DI through a Sansamp Classic pedal and then through a Ashdown 900 head and a cabinet, one 18–inch with two 10–inch speakers, and a Crown PZM mic four feet in front of it, on the floor. It was pure violence! The ceiling might have caved in, even though you don't hear that on the record. There was not too much distortion, but it was working really hard. I wanted to get some depth and some air behind some of the attacks. I ran the DI and reamp mics through a Gates Level Devil — a '60s tube compressor — and my 1959 Blonder Tongue B9b Graphic Tube EQ. The Blonder is a weird, rainbow–looking thing and it's my favorite thing on the bass. I got the phase the way I wanted it, and also added a Collins 26U compressor, and that was the bass sound."

- Guitars: Collins 26U, Cranesong Phoenix, Moogerfooger phaser, CBS Automax

"I didn't do anything to the verse electric guitars. They were were recorded the way we wanted them to sound. The electric guitars in the chorus were treated with a Collins 26U tube limiter. They brought out a bit of grain and added more weight to the single–note guitars. One electric was panned right and the other left, and the one on the right, which was played by Drew Brown, I used the Cranesong Phoenix Luminescent plug–in, which brings out the 300–800 Hz range and overtones, to give a nice full sound. The room sound that came with the guitar solo was treated with the Moogerfooger phase pedal. There were no other effects on the solo.

"Way underneath these guitars there are electric guitar overdubs in the chorus, playing open chords. I think one is a Telecaster and the other a Gibson 335 and they're playing through open–backed cabinets, probably a [Fender] Deluxe and a Twin. My first mix had these up loud with the acoustic in the middle. When I turned them down and the acoustic up, everyone was happy. As far as the acoustic is concerned, that initially wasn't quite working the way we wanted to. Ryan had played it four or five times, and I went back and grabbed another performance and stuck it on the track in the chorus. I think I used the CBS Automax tube compressor on it. Sometimes you have to go to great lengths to get things to work and I'll do whatever it takes to get there."

Joe Zook & The Unique Studio

Zook began his music career in his native Boulder, Colorado, but moved to Austin, Texas, at the age of 19. In 1996, he moved to Los Angeles, where he ended up assisting the legendary production duo of Mitchell Froom and Tchad Blake. "They did everything on 24-track analogue, 15ips, Dolby SR. Tchad Blake is the Jimi Hendrix of engineering to me. He doesn't do that much, it's all very simple, but even when you've seen him do it a million times, you can't duplicate it. When he left he would let me use his gear, and I would do everything I'd see him do, and it would still sound like a lame imitation. Tchad taught me to stop trying to be somebody else and just be myself." He moved on to work with the equally legendary Jack Joseph Puig for almost two years, and following this he went freelance, in 2002.

Zook established his own 4014 Mixing venture in 2004, with an unusual and extensive combination of state-of-the-art digital and obscure analogue gear. An unusual aspect of 4014 is the absence of a mixing desk, despite the fact that Zook professes that he "can't mix without analogue gear" and that he's "never been happy with an in-the-box sound".

"The mean reason for having my own studio is that it's much more creative," he explains. "It can take five days for the record company executive to listen to your mix, and the band may be in one state or country and the producer in another, and the manager also wants a say, and any of them could ask for a recall. If you've been working in a commercial studio, you often won't be able to get back into that room several days later. At my own studio I take really great notes, and I take digital photos of all my gear, so I have been able to do fast recalls.

"I use a Command 8 for fader rides, I need to be able to get my hands on faders. I need the different colours that my outboard gives me, but plug-ins have become so much better during the last three or four years. You have to remember that someone like Dave Hill from Cranesong used to design tube preamps and half-inch machines 30 years ago. And now he does plug-ins. The same with Bobby Nathan of Unique Recording Software. Universal Audio do a similar thing. The stuff these companies make is good!

"The main problem in working in the box was the sound. I don't like summing amps either, so I was designing things and had things built for me. It's been a real struggle, but I ended up with something that I think is fantastic. It's not easy to summarise the way my studio works, but the basic idea is to do summing like on a vintage Neve console, with line level taken down and summed by a passive summing system, and then amplified back up with Neve 1271 and 1272 preamps. My system is based on 32 channels of Folcrum. Most of the OneRepublic record was done with preamps made from UTC transformers and original API 2520 amps, but for 'Apologize' and 'Say' I used Neve 1272 preamps for a slightly less gritty sound.

"I work with really great techs and talk to them about how I want it to sound and they build a few things and I'll pick what I like and tweak it until I'm hearing what I'm after. As far as I'm concerned it's still a work in progress. I'm inspired by people like Tom Dowd, who built Atlantic Studios, and (probably) invented what we know as faders in the process, along with some of the first eight-track recorders. All the great studios, from Abbey Road to United Western to Crystal Sound to Sunset Sound, were just making shit up that they thought sounded cool, because they couldn't just go out and get a great-sounding studio at the local music store. They all had a beautiful unique sound because of this. Making a studio should be like making a record: you don't just use the stock preset on everything. You tweak it and make it fit the way that you feel music."