Many reverb plug-ins offer a choice of algorithms, each emulating a different type of space or mechanical response — room, plate, hall, chamber and so on.

Many reverb plug-ins offer a choice of algorithms, each emulating a different type of space or mechanical response — room, plate, hall, chamber and so on.

Reverb plug-ins can present a bewildering variety of parameters. We explain what they're there for, and how to put them to good use!

When we sing or play an instrument, the sound spreads out in all directions. Some of it travels directly to the listener or microphone. The rest arrives there in roundabout ways, after bouncing off one or more surfaces.

Because there are lots of possible paths from the source to the listener, we don't hear this reflected sound as a single echo. Instead, thousands of smaller echoes arrive in a short space of time. These merge to form a wash of sound which we call reverberation. Different spaces reverberate in different ways, and the human ear is very good at picking up on these differences. In recording, the quality and character of the reverberation are vital.

Especially if we're recording in a domestic house, however, natural reverberation won't sound pleasing on everything. We deal with this by placing the microphone close to the source, to capture mostly direct sound, and then adding reverberation artificially.

Most of us now do this in software, and even the most basic DAW program will come with several plug-in reverbs. But, unlike a real room, a typical reverb plug-in offers endless ways to modify the sound. So what do all those controls actually do, and how do you tailor a reverb to get what you want from it?

A Room Of One's Own

Reverb plug-ins usually don't just have one reverb algorithm. You'll often have the option to choose from a list that might include one or more rooms, halls, plates, ambiences and so on. As the names suggest, these are optimised for recreating particular types of reverb. Choosing a new algorithm is often the most important single thing you can do to vary the sound of the plug-in. Algorithms such as room, hall and church are fairly self-explanatory, but a few other common types are worth explaining:

- Plate recreates the sound of electro-mechanical reverbs such as the classic EMT 140. These behave rather differently from real spaces, and have a characteristic dense, 'sizzly' sound.

- Ambience is a term usually reserved for very short reverbs. In a mix, these are often audible less for their spaciousness and more for their effect on the tone of the source. A bright ambience can add the sort of sparkle you might otherwise get using treble boost or an aural enhancer, while a darker one can thicken up drums and other sources.

- Non-linear reverb algorithms are used mainly on drums, and are designed to be inherently unnatural. They reverse the usual dynamic envelope, yielding a reverb that builds up slowly and then suddenly cuts off.

The same controls are usually available in all the algorithms, but they may have different ranges depending on which algorithm you've chosen. For example, the range of decay times available for a hall or church setting might run from 2 to 10 seconds, while an ambience algorithm might run from 100ms to 1 second.

What About Convolution?

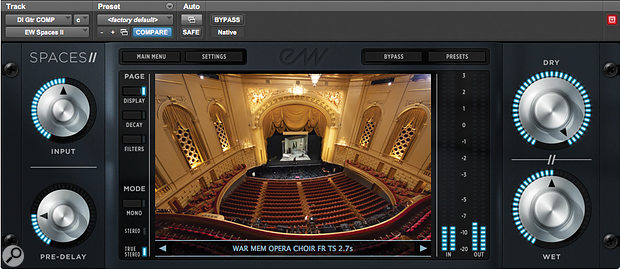

Convolution reverbs such as EastWest's Quantum Leap Spaces II are generally quite simple to use, and offer few parameters for adjustment beyond simply loading up a new space.

Convolution reverbs such as EastWest's Quantum Leap Spaces II are generally quite simple to use, and offer few parameters for adjustment beyond simply loading up a new space.

Plug-in reverbs use one of two technologies. In a convolution reverb, a gunshot or other impulse is fired into a real space and the results are recorded as an 'impulse response', which can then be imposed onto any source. In an algorithmic reverb, the way in which individual reflections bounce around and recombine is simulated in real time. Convolution reverbs tend to be quite simple to use, as the main thing you can do to change the sound is load in a different impulse response. In this article, therefore, I'm going to focus on algorithmic reverbs.

Pre Possessing

Before the reverb algorithm gets to work, though, we encounter the all-important pre-delay control. This introduces a gap to separate the dry sound from the reverb that follows it. With no pre-delay, source and reverb merge together. With a long pre-delay, the source sound retains its dry character and sits in front of the reverb.

The pre-delay parameter — the leftmost slider in Softube's TSAR-1 plug-in — delays the onset of reverb, making sounds appear closer to or further from the listener at long or short settings respectively.One way to understand the psychoacoustic effect of pre-delay is to imagine standing in the middle of a hall. A long pre-delay makes it feel as though the sound source is next to you in the middle of the hall. With no pre-delay, by contrast, it feels as though the source is far away on the edge of the hall, with the direct sound being immediately followed by the reflected sound.

The pre-delay parameter — the leftmost slider in Softube's TSAR-1 plug-in — delays the onset of reverb, making sounds appear closer to or further from the listener at long or short settings respectively.One way to understand the psychoacoustic effect of pre-delay is to imagine standing in the middle of a hall. A long pre-delay makes it feel as though the sound source is next to you in the middle of the hall. With no pre-delay, by contrast, it feels as though the source is far away on the edge of the hall, with the direct sound being immediately followed by the reflected sound.

For obvious reasons, long pre-delays work better with fairly expansive reverbs than with tight ambiences. A short or non-existent pre-delay is often perfect for rock drums, where the decay of a snare hit blends with the added reverb to create something bigger and meatier. On other sources, it can help to bed things into the mix, so can be ideal for background guitar or keyboard parts. Long pre-delays, by contrast, are particularly useful on vocals and lead lines, where you want to add lushness and thickness without detracting from the immediacy of the part. Long pre-delays also help to preserve the intelligibility of vocals and intricate solo parts. Don't be afraid to dial in 100ms or more if it works, and don't overlook the option to make the pre-delay time a musically significant interval such as an eighth or 16th note.

Nearly all reverb plug-ins offer pre-delay as a parameter, but there are times where you might want to set it up another way. Back in the day, engineers would implement pre-delay by feeding the signal through a tape machine in record mode, varying the tape speed to change the delay time; this is easily recreated using a tape echo plug-in, for a more retro sound. You might also want different sources to have different pre-delays, even if they're feeding the same reverb. When you record an orchestra, the first violins will typically be nearer the 'listener' than, say, the timpani at the back of the stage. To mimic this positioning with dry sampled instruments, you might want to use a long pre-delay for the strings, a shorter one for the woodwinds and so on. This is best done by setting up several different busses with short delays on them, and routing all of them to the same reverb bus.

Imagine standing in the middle of a hall. A long pre-delay makes it feel as though the sound source is next to you in the middle of the hall. With no pre-delay, by contrast, it feels as though the source is far away on the edge of the hall.

Early Doors

Perfectly simulating the behaviour of sound in real spaces would require immense processing power, so algorithmic reverbs don't model the behaviour of every single reflection. Typically, they use individual delays to simulate the most prominent ones, which reach the listener first. The later, secondary reflections that form the reverb 'tail' are then approximated, for example by feeding the initial reflections into further recirculating delays. Consequently, many plug-in reverbs offer separate controls for the early reflections and the reverb tail.

Most plug-ins allow you to adjust the balance between early reflections and the reverb tail, and some — like Waves' H-Reverb — provide options for different early reflection 'shapes'.

Most plug-ins allow you to adjust the balance between early reflections and the reverb tail, and some — like Waves' H-Reverb — provide options for different early reflection 'shapes'.

In some plug-ins, the only thing you can do to the early reflections is adjust their level. Even so, this opens up plenty of possibilities. If your reverb allows it, try feeding it an acoustic guitar track and muting the reverb tail altogether, to leave only the early reflections. What you'll hear might sound more like EQ or treble enhancement than reverberation as such: heard on their own, the early reflections arrive so quickly that the ear can't separate them from the source. It's a virtual counterpart of the old recording engineer's trick of placing a sheet of hard material on the floor in front of the guitarist to add liveliness and sparkle. A short, sharp dose of early reflections can be equally effective on lifeless drum overheads, boring digital pianos, dull-sounding strings and so on.

More advanced plug-ins might give you control over the spacing and tone of the early reflections. In the real world, these are important psychoacoustic cues that help to tell us about the shape and size of the room we're in. For instance, in a tiled bathroom, all the early reflections will reach us at nearly the same time, and they'll all be relatively bright. In a larger space, the early reflections will be more spread out, and may be darker, owing to the high-frequency absorption of the air through which they've travelled. An empty square room will produce a handful of very strong early reflections, while a cluttered, oddly shaped space will generate many more, weaker ones.

In rock and pop mixing, realism is less important than whether your choices work for the track. Dense, bright early reflections can be great for snare drums or overheads, but on a vocal, they might exaggerate consonants and sibilants. Having lots of early reflections spaced quite evenly makes for a smooth, rich effect that benefits many sources, but the opposite can work well on instruments such as electric guitars. If you want a reverb to work 'behind' the source, or if you're trying to imitate a spring or plate sound, you could even try muting the early reflections altogether.

Tone & Time

When it comes to the main part of the reverb, there is endless variation in the controls offered by different plug-ins. This means not everything I'm about to say will be universally applicable, but hopefully it should be possible to translate it to your reverb of choice! Broadly speaking, we can divide the controls into two categories: those that determine the timbre or character of the reverb, and time-related controls that adjust the duration and 'shape' of the reverb decay. These often interact and, as I've already mentioned, will be operating within limits that are set by the chosen algorithm.

Reverberation consists of thousands of reflections, all arriving within a short space of time so that they end up superimposed on one another. We don't hear these as individual echoes, but we can certainly detect variations in their overall pattern. As we've seen, some reverbs allow the spacing of the early reflections to be varied, and nearly all of them provide a similar sort of control over the reflections that make up the main body of the sound. The key parameter here is diffusion, sometimes known as density.

In an empty room, individual reflections from each wall remain relatively coherent as they bounce around the room, so what we hear is more like a series of distinct echoes. In a cluttered space, by contrast, reflections are quickly broken up as they encounter other objects and surfaces, and the pattern becomes much more chaotic. Diffusion simulates this behaviour. At its lowest settings, the reverb tail will sound grainy, thin and perhaps even metallic; you may even be able to detect 'flutter' on transients. At maximum diffusion, by contrast, the tail will be dense, smooth and lush.

You might think that one of those extremes sounds a lot more appealing than the other, and in a sense you'd be right. However, context is everything, and not every source benefits from the thickest possible reverb. By all means crank up the diffusion on a snare drum and enjoy the beefiness and substance that it adds, but don't neglect the possibilities that lurk at the other end of the dial. A thinner, less diffuse reverb takes up less space in the mix, and often has a more individual character; electric guitars in particular often seem to benefit from reverbs that might sound grainy and coarse on other sources.

Size Isn't Everything

Turning next to the fourth dimension, let's consider some of the most important controls that affect the length of the reverb, and how you can use them to your advantage. If you're familiar with basic synth programming, you'll have come across the concept of an envelope. In its most basic form, the envelope of a reverb has two sections: an attack phase during which it builds up to maximum amplitude, and a decay phase during which it drops away to silence. The attack phase is usually short or even instantaneous, while the decay time can be as little as half a second in a small, dead space, or more than 10 seconds in a huge cathedral.

IK Multimedia's CSR offers a 'Breathing Drums' setting — a non-linear reverb that builds up slowly before suddenly cutting off.

IK Multimedia's CSR offers a 'Breathing Drums' setting — a non-linear reverb that builds up slowly before suddenly cutting off.

Once again, the most important factor governing the envelope of the reverb is the choice of algorithm. In a non-linear algorithm, for example, the usual envelope is reversed to give a long attack and short decay. Within each algorithm, though, you'll usually have the option to specify both decay time and room size. These work together to determine how long the decay phase of the reverberation lasts, again within limits set by the algorithm choice.

There might be many different combinations of decay time and room size that yield a two-second reverb, but the character and 'shape' of that reverb will be very different. A smaller room brings the listener closer to the action and makes things feel lively and energetic, which can be ideal if rock & roll excitement is what you're looking for. A larger space has the potential to sound rich and expansive. Setting up a large hall for a two-second decay will give you something that sinks into a mix and might help to bed multiple sources together; extending a bathroom reverb to two seconds will produce something that draws attention to itself, and which might be more useful as a special effect on one source only. Some reverbs give you control over the shape of the virtual space as well as its size, and there's a considerable difference between the sound of a cubic room and a corridor of equivalent volume!

So how long should your reverb be? Almost as long as the proverbial piece of string! There are no absolutes, but in general, faster or busier tracks and parts leave less space for long reverbs than down-tempo, sparse pieces. If you're applying more than a smidgeon of reverb to anything rhythmic or repetitive, you'd usually want to keep it short enough that each hit's reverb dies away before the next one comes around. In a punk rock track, you might stick to a tight drum room or ambience on the snare and toms, and a slapback delay on the vocals; in a lush ballad, you might have several different three- or four-second reverbs layered on the vocal alone.