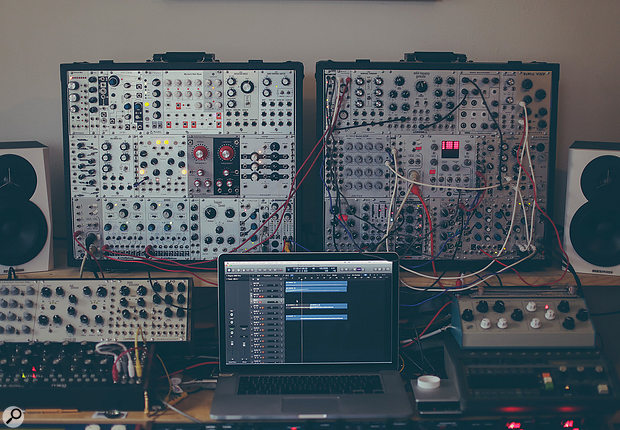

Kyle Dixon (foreground) is joined in his studio by collaborator Michael Stein. As one half of Austin-based electronic act Survive, the pair have amassed an enviable array of vintage and modern synthesizers. And you haven’t seen Michael’s studio yet... Photo: All Alex Kacha

Kyle Dixon (foreground) is joined in his studio by collaborator Michael Stein. As one half of Austin-based electronic act Survive, the pair have amassed an enviable array of vintage and modern synthesizers. And you haven’t seen Michael’s studio yet... Photo: All Alex Kacha

Cult TV series Stranger Things has become essential viewing — and essential listening. We talk to the previously unknown composers behind its hit soundtrack.

If you’re not familiar with Stranger Things, the sci-fi mystery TV show commissioned by Netflix and starring ’80s screen legend Winona Ryder, you’re missing out. The plot follows a group of misfit kids looking for their missing friend (the missing child’s desperate mother is played by Ryder), a girl who has seemingly appeared from nowhere, and a shadowy government agency meddling with forces they cannot control. Set in the fictitious town of Hawkins, Indiana in the 1980s, it’s very much in the vein — both thematically and visually — of a Stephen King, Spielberg or John Carpenter endeavour. King himself even said watching it was like watching his own greatest hits.

With nods at Carpenter, Tangerine Dream and Goblin, among others, the programme’s synth-dominated soundtrack is absolutely vital in creating the atmosphere of rose-tinted ’80s nostalgia. It quickly became the invisible hero of the show, and within moments of the first season appearing online, viewers were clamouring for the soundtrack to be released. In fairly short order, it was (in two volumes) and, at the time of writing, it has been nominated for several awards, including a Grammy.

Opportunity Knocks

The show was created and directed by relative unknowns the Duffer Brothers, whose biggest prior credit had been directing a handful of episodes of M Night Shyamalan’s TV show Wayward Pines. Perhaps it’s fitting, then, that they approached Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein to score the show — for they, too, were newcomers, never having scored a TV show before. The closest they had come was to have a couple of tracks on the soundtrack for 2014’s mystery thriller The Guest.

Despite this, the Duffers seem to have had Kyle and Michael in mind early in the process, reportedly using a track by the pair’s band, Survive, when pitching the show to TV execs. Once the series was greenlit, the directors immediately approached Dixon and Stein. This isn’t the sort of thing that often happens if you’re a newcomer to media composition, as Dixon admits. “There was definitely luck involved with them finding us and reaching out, but we absolutely worked to get the job. We worked every night after our day jobs to write demos, and there was no guarantee that we would be hired. This is something that we’ve always wanted to do, so when someone approached us with a very legitimate opportunity we jumped at it with no hesitation.”

Light & Dark

The directors’ vision was clear from the outset, as Stein explains. “They really wanted something that felt classic but was also modern and not too kitschy.”

That’s easier said than done, though: “Since the series teeters between wholesome family time and government-funded dimensional travel where there happens to be some sort of monster, we had a decent amount of ground to cover. When making a synth-driven score for horror, it can be very easy to end up with something that sounds a little cheesy, but we tried to keep it as classy as possible,” says Dixon.

“We followed up by sending them about 50 tracks from libraries Kyle and I had been putting together for this exact reason,” adds Stein. “A collection of different moods, themes and sound beds that we felt would be good for film. They were very enthusiastic to hear these and requested we pitch some original ideas created for them. They knew we could do textural, darker and epic stuff so they had us make themes for the kids and [character] Eleven, to prove we could deliver in the more sentimental moments. They later paired these tracks up with the cast audition tapes which ultimately helped them make casting decisions and solidified our involvement against the other composers who were also pitching.” Little wonder the soundtrack seems so integral to the series!

Switched On Synths

Like every overnight success, Dixon and Stein’s big break had been a long time in the making. “I got seriously into music near the end of high school,” says Stein. “Experimenting with recording and processing instruments led to me collecting all kinds of hardware over a number of years.”

Things got taken up a notch when he got into buying synths and drum machines. “I started buying/building a 5U modular when Eurorack was almost solely Doepfer. I was attracted to the DIY aspect — it was the most exciting step in experimenting with making sounds and manipulating audio. I wanted to do sound design at the time, but naturally started making compositions.”

Stein continued further down the audio engineering route, studying it at Media Tech in Dallas to improve his recording and mixing chops. “I’ve always admired experimental producers or engineers in the pop world, whether it’s Joe Meek, Brian Eno, Trevor Horn or Mike Will — basically people who bring some sonic mystery to something so refined and marketable as pop.”

It was around this time, while studying, that Stein reconnected with childhood friend Kyle Dixon and the pair began making music together. Concurrently, Stein co-founded a recording studio in Dallas with producer/engineer Jeremy Cox and Will ‘Prince Will’ Boston, mainly working with producers and rap artists. “Simultaneously, things really started to develop musically with Kyle and now additionally Mark and Adam [the other two members of Survive]. We had formed Survive, and either I was in Austin every other weekend writing music and playing Survive shows, or they were in Dallas at my studio. It was very apparent how seriously we were taking the project, so when I finished school we closed the studio and I moved out to Austin in early 2010.”

Luckily for Stein, friends had started up an electronic music store in Austin called Switched On, and recruited him to work at the shop repairing and selling synthesizers. “I continued working here, constantly experimenting/writing at my home studio, and would do recording and production work for some other local acts such as Sleep Over, Ssleeperhold and Boan on the side. The was my main routine until composing for Stranger Things. Luckily, now I am able to work on music full-time, which is great.” says Stein.

Worlds Collide

Survive released their second long-player, RR7349, in September — but, as Dixon says, “RR7349 was finished before we started working on Stranger Things, so there wasn’t any direct influence from our scoring work on that album. The two processes are very different in a lot of ways. We still use many of the same instruments for both, but the goals, and therefore the tones, are different. With the Survive albums there is a somewhat strict line of what won’t be released, as we typically keep a less playful, and more serious mood on the albums.”

Compared with writing songs for Survive, Stein finds the process of composing for television to be much more directed. “Writing for TV is great because you have a very clear objective going into it. ‘This scene needs music like this,’ vs ‘Hmmm, what kind of song should I try to make?’ The latter has endless opportunities.”

Kyle agrees: “Writing a song can be much more difficult. Because the music written for film/TV has the goal of supporting the story, there is a lot less pressure on the music. For one, you don’t have to worry about making a statement with the music you write: you are simply supplementing the story. I find the constraints of a story and length of a scene to make the writing process quite a bit easier. There are many cases when a scene is just far too short for you to write a full-on song, so essentially you are just writing one part of a song, and there is no reason to even consider writing a bridge or chorus.”

Synths In Soundtracks

While many media composers now work entirely ‘in the box’, that wasn’t an option for a duo and a project whose sound world depends to a great extent on vintage synths.

Stein and Dixon would split their time between their respective studios when creating the score. Here, in his own studio, Stein works with an Akai MPC to sequence parts. His impressive collection of classic synths includes a Korg Mono/Poly, a Sequential Circuits Pro-One, a Prophet VS Rack, an ARP 2600 and an Oberheim Two-Voice, along with Eurorack and 5U modular systems.

Stein and Dixon would split their time between their respective studios when creating the score. Here, in his own studio, Stein works with an Akai MPC to sequence parts. His impressive collection of classic synths includes a Korg Mono/Poly, a Sequential Circuits Pro-One, a Prophet VS Rack, an ARP 2600 and an Oberheim Two-Voice, along with Eurorack and 5U modular systems.

Stein: “For scoring, I may start laying down takes directly into Logic to the picture, very loosely because it’s not usually very rhythm-oriented. But I typically scratch compose on an [Akai] MPC to get ideas out, and then I’ll also have the note information saved as MIDI. I have various MIDI to CV/Gate, and clock or MIDI to DIN converters to get all the analogue equipment sync’ed up for the foundation of a track. I used to slave the hardware sequencers to Logic and print to the timeline directly on the grid, but lately I just listen to the click and punch in for overdubs. My friend José Cota and I refer to this as ‘air sync’. I’ll usually print a summed guide track so I can hear the groove of the original composition, especially if I’m going back and multitracking from something as wavering as the TR-808. Then I’ll align by listening and looking at the visual transients. This leaves some space to slip the groove a little if preferred. I recently got a Sequentix Cirklon and that should improve my overall master clock compared to the MPC.”

“For the longer, more structured cues the MPC is the master sequencer, sending MIDI to all the various synths,” adds Dixon. “Obviously, most of the synths don’t have MIDI, so there are a few MIDI-CV converters around. Many of the more atmospheric cues are recorded in a more organic type of way, where we will just create a new session, make some sounds we want to work with and then record for a while, then take the best parts or sections that work for certain types of moods. Not everything needs to be created specifically for a scene, and trying different cues out over scenes that they weren’t necessarily written for has yielded some very good results.”

To make things easier, they have also modifed much of their pre-MIDI equipment, as Stein explains. “I’m definitely open to modding my equipment — mostly for basic functionality, not so much the Frankenstein hacks. For instance, I have MIDI on my Roland Jupiter 8 and I added a CV/Gate mod to my Korg 770 so I can sequence them, that kind of stuff. The drum machines see a lot heavier modding: trigger and clock I/O, pitch control, individual outs and so on, but we didn’t really use much of that on the score.“

The 'monster theme' was sequenced using the eight-step Encore Event Generator in Stein's enormous 5U modular system

The 'monster theme' was sequenced using the eight-step Encore Event Generator in Stein's enormous 5U modular system

Kyle adds: “Most of the mods that I have are for basic functionality, like triggers or CV/Gate, although I do have some circuit-bent stuff that was fun to play with before it eventually broke.”

Even so, using vintage instruments presents certain challenges that Stein and Dixon had to overcome. The first is the issue of parameter automation. Kyle’s advice is simple: “Use your hands! It gets a bit tricky when you have more than a couple of synths that need to be tweaked at the same time, but we’ve managed to do it.”

Stein adds: “If it’s just filter sweeps and envelope expression, I’ll just do passes until I get it about 90 percent on, and then the final nuance can be automated with EQ in mixing.”

Going Back In Time

Today’s media composers are also expected to be able to recall sessions in order to make last-minute changes. With Stein and Dixon’s setup, this was rather more difficult than just opening up a DAW session. To make recalls more manageable, Stein bought a Dave Smith Instruments Prophet 6, which has patch memories, but still lived in fear of having to recreate certain sounds. “There were times I was kind of terrified if they wanted a revision. For instance, on the track ‘The Upside Down’, the creepy lead melody was programmed on an eight-step analogue sequencer in my 5U modular. The notes are all detuned in a very subtle way you can’t play on a keyboard, so luckily I had two of those sequencers [the Encore Event Generator] and I literally never touched it for six months, out of fear they would want me to recall it. I would also record a few different tempos of cues for pacing just in case. Sometimes you have to redo something and getting it close is perfectly suitable,” He says, “I remind myself that the completed piece of music is more important than replicating a patch exactly or doing the perfect performance, because those things are really easy to get caught up on and slow progress.”

While the keyboard instruments were used more for melodic and harmonic content, the modular rigs served Stein and Dixon well for creating some of the show’s signature warped, textural elements that give the score so much of its atmosphere.

While the keyboard instruments were used more for melodic and harmonic content, the modular rigs served Stein and Dixon well for creating some of the show’s signature warped, textural elements that give the score so much of its atmosphere.

Kyle: “We had that monster sequence on the 5U forever, just waiting for them to ask us to remake it! Once we got into the score we began to reuse synths for similar sounds, so it got easier. Some cues we just couldn’t recreate, so we would have to process them or write over them if revisions were requested. The Prophet 6 was very helpful because it actually saves patches — a luxury that doesn’t exist with modular synths, or 90 percent of the synths we own, for that matter.”

Whatever Works

Vintage synths are central to the sonic character of the Stranger Things soundtrack, but as Kyle explains, there’s a lot more to it than that. “The score is primarily analogue synths, but we aren’t trying to pretend we are living in the ’80s. After all we do record into computers! Obviously we are using almost exclusively synthesizers, so that’s part of it, but a lot of what defined the sound isn’t necessarily what we were doing, but what we weren’t doing. We didn’t use much resonance on our tones, and we generally kept the cutoff on bass parts low, so the synths weren’t too growly. This is obviously not a strict rule, but was often the case.

Tape delays are used liberally on the soundtrack. Stein’s studio boasts tape delays from Roland and Korg, as well as the less common Tel-Ray Ad-n-Echo oil-can delay."We typically use a lot of tape echo, and [Eventide] Harmonizer to add texture. If we used digital synths or plug-ins, it’s not uncommon to for us to run them out to an analogue delay or tape echo to warm them up, or even just roll some of the high end off with EQ. Some of the more bizarre textural stuff was made using our modular synths.”

Tape delays are used liberally on the soundtrack. Stein’s studio boasts tape delays from Roland and Korg, as well as the less common Tel-Ray Ad-n-Echo oil-can delay."We typically use a lot of tape echo, and [Eventide] Harmonizer to add texture. If we used digital synths or plug-ins, it’s not uncommon to for us to run them out to an analogue delay or tape echo to warm them up, or even just roll some of the high end off with EQ. Some of the more bizarre textural stuff was made using our modular synths.”

What’s more, the duo were happy to embrace more modern sound sources when they were right for the job. “We made really good use of two soft synths for the score. Both are vocal engine-style synths,” says Stein. “We like using any equipment for what it excels at, and are not strictly analogue purists. We won’t use a soft synth for an ‘analogue’ bass tone when an analogue synth does it best. I do prefer tones from ’70s synthesizers the most, but I have also always had hybrids in the studio, like the Prophet VS or Ensoniq SQ80. I also like to run digital synths through analogue processing. I have a handful of vintage digital synths and modern wavetable VCOs that are great. We embrace modern technology but find it most rewarding to create music using hardware synths. Everything has its strengths and weaknesses.”

Feel It Out

When it comes to capturing the output of their instruments as audio, Stein and Dixon don’t tend to fuss over the minutiae too much, focusing their attention instead on the final sound. “My recording chain varies from track to track,” says Stein. “I don’t get too caught up in it. As long as you have a decent interface and watch your gain staging, it’s fine. I’m a fan of UAD, Apogee and RME [interfaces], which were all used for recording. Even if something is clipping a little and you didn’t notice it till after tracking, it’s probably because you liked the way it sounds. Typically it just adds some texture and character. Clean can be boring and distortion can sound terrible, so it’s subjective, but usually I’ll embrace it and do some tricks with it in mixing, unless it’s pure crap. Then it’ll get redone. I am almost solely mixing with Logic’s native plug-ins and UAD. Also SoundToys and some Eventide stuff for in-the-box effects.”

Kyle adds: “While it would be great to record through a really nice board, and I’m sure it would sound great, we don’t have one. Our recordings were all made on relatively cheap interfaces compared to most professional setups. We use a decent amount of outboard effects, but also rely on a lot of the plug-ins Michael mentioned. Sometimes using outboard effects is a terrible idea, if for instance you know there may be changes, and you have time-sync’ed delays that may need to be manipulated later.”

“As far as mixing and mastering for TV goes,” says Stein, “I’ve read people saying ‘Slam the limiter so people can hear your music cut through under all the dialogue and effects.’ I just stuck to my usual techniques and made the mixes warm and dynamic and have more low end than most music on TV. I think it came out great, so who knows! There were definitely instances when you could tell you were competing with on-screen sound and effects, so you end up making the balance of certain instruments very different than what you would do in an album so the right parts of the track would cut through. Usually I just feel it out for each cue and if I was unsure I would send over stems of my mix to give the post engineers more control.”

Things To Come

With all the praise being thrown at Michael Stein and Kyle Dixon’s soundtrack, it’s hardly surprising that they’re returning for the renewed season of Stranger Things. Considering how quickly rumours spread online, Kyle was expectedly tight-lipped on the current production. “We are currently working on Season 2, but we can’t get into many details about what to expect. It has been made public that there are new characters and the season will probably be a bit darker. The people of Hawkins did just go though some fairly traumatic events!”

Stranger Things is scheduled to return to our screens later in 2017, and for those who can’t wait until then to get their fix of atmospheric synth-wave madness, Survive’s RR7349 is out now.

Stranger Things Title Theme

When viewed on Logic Pro’s timeline, the complex layering within the Stranger Things theme is quite apparent. In creating the soundtrack to Stranger Things, Michael Stein and Kyle Dixon were helped enormously by having a body of work to draw upon from their band Survive — no more so than when it was time to create the show’s title theme. Stein: “There was not that much of a brief [from the directors] for what the theme needed to be. Early on, before there were approved title graphics, it was more ‘What do you got?’ After the Duffers sifted through some old and new compositions, they really liked the mood of a demo I’d made for Survive that probably never would have seen the light of day. I set up the MPC to re-sequence all of the parts live in the room so I could rewrite the arrangement and come up with additional parts. After about three renditions there was something in the ballpark of what you know as the theme.”

When viewed on Logic Pro’s timeline, the complex layering within the Stranger Things theme is quite apparent. In creating the soundtrack to Stranger Things, Michael Stein and Kyle Dixon were helped enormously by having a body of work to draw upon from their band Survive — no more so than when it was time to create the show’s title theme. Stein: “There was not that much of a brief [from the directors] for what the theme needed to be. Early on, before there were approved title graphics, it was more ‘What do you got?’ After the Duffers sifted through some old and new compositions, they really liked the mood of a demo I’d made for Survive that probably never would have seen the light of day. I set up the MPC to re-sequence all of the parts live in the room so I could rewrite the arrangement and come up with additional parts. After about three renditions there was something in the ballpark of what you know as the theme.”

Stein’s Roland Jupiter 8 has been retrofitted with MIDI and picks out the lead part in the Stranger Things theme. The Jupiter 6 was equipped with MIDI on its release.As far as credit sequences go, Stranger Things seems to have a relatively simple one. The title glows in red as the words gravitationally pull together over the course of about a minute. Like so much of the show, though, its complexity lies in the references it makes. Even the font used is lifted from Stephen King novels of the 1980s and the Choose Your Own Adventure children’s books. Likewise, although the musical cue may not seem vastly complicated, there’s more going on than is immediately apparent, as Stein explains: “The theme consists of roughly 25 tracks and 25 various synths. The list spans across the board. There’s [Korg] Mono/Poly arpeggios, [Roland] Jupiter 8 leads, Mellotron M400 choir stabs, [Sequential Circuits] Prophet 5 and 6 and VS pads and effects, [Roland] SH-2 on the bass line, [Sequential] Pro-One does the heartbeat thumps, and an original Oberheim SEM Two Voice playing the main arpeggiated sequence, to name a few. There is a lot of layering of the same part, which is a very common technique I use for mood and depth.

Stein’s Roland Jupiter 8 has been retrofitted with MIDI and picks out the lead part in the Stranger Things theme. The Jupiter 6 was equipped with MIDI on its release.As far as credit sequences go, Stranger Things seems to have a relatively simple one. The title glows in red as the words gravitationally pull together over the course of about a minute. Like so much of the show, though, its complexity lies in the references it makes. Even the font used is lifted from Stephen King novels of the 1980s and the Choose Your Own Adventure children’s books. Likewise, although the musical cue may not seem vastly complicated, there’s more going on than is immediately apparent, as Stein explains: “The theme consists of roughly 25 tracks and 25 various synths. The list spans across the board. There’s [Korg] Mono/Poly arpeggios, [Roland] Jupiter 8 leads, Mellotron M400 choir stabs, [Sequential Circuits] Prophet 5 and 6 and VS pads and effects, [Roland] SH-2 on the bass line, [Sequential] Pro-One does the heartbeat thumps, and an original Oberheim SEM Two Voice playing the main arpeggiated sequence, to name a few. There is a lot of layering of the same part, which is a very common technique I use for mood and depth.

“A key element to the production of the theme was having the right amount of ‘murk’, which is commonly considered a negative thing in production. There are a lot of musical elements layered to create a bedding under the track that sort of breathes and adds a lot of the mystery. There’s an arpeggiated mellow piano part on a Prophet 5 that you can’t even hear, but if I take it out, the mood is lost. It’s a mingling of subtle nuances that makes this surprisingly major-key theme work in a mystery sci-fi drama context. I think the aggressive bass tone of the SH2 really helped set the dark tone. It has a balance of hope haunted by the weirdness element. In my opinion this is why it works to reinforce the story.”

Two Cues

The Oberheim SEM Two Voice carries the main arpeggio line within the title sequence. Above the SEM is Michael’s Eurorack rig, which was used for some of the more outlandish sounds, and sneaking in from the right is an Arturia MicroBrute.Photo: Alex KachaAmong the most significant cues in the whole Stranger Things series are two that represent recurrent themes and events. One such is ‘Kids’. It’s dark outside, and our main protagonists — the group of misfit kids — end a game of Dungeons & Dragons and cycle away from the house on Choppers. Kyle describes the importance of the cue. “Well, this is the first time you actually hear any music in the show, so it was a big cue for the Duffers. This is where we establish Hawkins as a quaint little town and introduce our main characters who are about to have their lives changed forever. We tried a bunch of different ideas, but ended up using a version of one of the early demos we made for general kid-sounding stuff. There is an element of anticipation that we needed to convey, so there is a somewhat strange bass note that drones for most of the beginning of the cue that adds a bit of tension.

The Oberheim SEM Two Voice carries the main arpeggio line within the title sequence. Above the SEM is Michael’s Eurorack rig, which was used for some of the more outlandish sounds, and sneaking in from the right is an Arturia MicroBrute.Photo: Alex KachaAmong the most significant cues in the whole Stranger Things series are two that represent recurrent themes and events. One such is ‘Kids’. It’s dark outside, and our main protagonists — the group of misfit kids — end a game of Dungeons & Dragons and cycle away from the house on Choppers. Kyle describes the importance of the cue. “Well, this is the first time you actually hear any music in the show, so it was a big cue for the Duffers. This is where we establish Hawkins as a quaint little town and introduce our main characters who are about to have their lives changed forever. We tried a bunch of different ideas, but ended up using a version of one of the early demos we made for general kid-sounding stuff. There is an element of anticipation that we needed to convey, so there is a somewhat strange bass note that drones for most of the beginning of the cue that adds a bit of tension.

The Sequential Prophet 6 was used heavily in the score. Having patch memories made recalls much more manageable for the pair, meanwhile the ARP Avatar covered bass duties on the ‘Kids’ theme.The [DSI] Prophet 6 plays a few of the parts, ARP Avatar for the bass, Univox Mini-Korg for the melody and Oberheim SEM for the high arpeggio during the biking scene. The Prophet 6 got used a lot on this score. Because it’s new, it has some handy features [such as patch recall, MIDI and remote parameter control] that the older polysynths do not.”

The Sequential Prophet 6 was used heavily in the score. Having patch memories made recalls much more manageable for the pair, meanwhile the ARP Avatar covered bass duties on the ‘Kids’ theme.The [DSI] Prophet 6 plays a few of the parts, ARP Avatar for the bass, Univox Mini-Korg for the melody and Oberheim SEM for the high arpeggio during the biking scene. The Prophet 6 got used a lot on this score. Because it’s new, it has some handy features [such as patch recall, MIDI and remote parameter control] that the older polysynths do not.”

A contrasting but equally important cue is the music that viewers come to associate with the shadowy nether-world, or ‘Upside Down’. This represents a much darker side of the programme, and has an accordingly more sinister score.

Stein: “The Upside Down was a result of the directors requesting a ‘monster theme’. The only reference was to have a signature similar to Jaws, in the sense of being something simple and yet easily recognisable. The backbone of this song is an eight-step sequence that utilises only four ‘notes’. When you hear it, you know it’s referencing the monster, or the monster could be present. Part of what makes something so simple so effective is that the sequence was purposefully programmed on an eight-step analogue sequencer in my 5U modular that is unquantised — not locked to any particular scale. Every note has a subtle detune to create the desired amount of dissonance and tension. This is something you couldn’t play on a keyboard and achieve the same mood. It is musical but it is also unsettling. Combined with some rising dissonant pads from the very cinematic-sounding [Moog] Polymoog, woozy sub-bass and bombastic percussion blast from an ARP 2600, it’s pretty intense.”