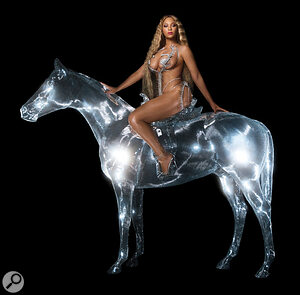

Beyoncé’s chart‑topping album Renaissance showcases a production process that’s all about staying in the moment.

“When I’m working with an artist, it’s all about the original, initial feeling that you get on the first day of recording. If I get off‑track while mixing a song, to find my way again, I’ll go back and listen to what happened on the first day, and how it felt emotionally and sonically. It will not be perfect, but the bulk of the feeling is there, and that’s what I’m always paying attention to.

“For example, the opening track of Beyoncé’s new album, ‘I’m That Girl’, came together mostly on the day we recorded her vocal. I think we did 90 percent of the mix of that song the day we tracked it. Several of the tracks on the album were like that, even as we worked on some others over a long period of time.”

Stuart White is describing what appears to be a new trend. More and more engineers are talking about the importance of the initial feeling when the main recordings go down. It involves keeping sessions simple, using mistakes and accidents creatively, mixing quickly and, often, working on location. At heart, it means letting go of the time‑consuming and energy‑draining second‑guessing that appears to be the inevitable side‑effect of working in a DAW.

Stuart White is describing what appears to be a new trend. More and more engineers are talking about the importance of the initial feeling when the main recordings go down. It involves keeping sessions simple, using mistakes and accidents creatively, mixing quickly and, often, working on location. At heart, it means letting go of the time‑consuming and energy‑draining second‑guessing that appears to be the inevitable side‑effect of working in a DAW.

Since 2012, Stuart has been Beyoncé’s personal engineer and mixer, and particularly during the making of her latest album Renaissance, he has been moving more strongly in a direction that emphasises performance, speed and spontaneity over technology. Elsewhere in this issue, Jason ‘Cheese’ Goldberg tells a similar story about his work with rapper YoungBoy Never Broke Again.

Don’t Sweat The Small Stuff

Having cut his teeth working with Russell Elevado, Ann Mincieli and Tony Maserati, White has been around at the top level since he started his career at Quad Studios, NYC in 2002. His credits include Alicia Keys, Nicki Minaj, Sia, Jay‑Z, Nas, FKA Twigs, Megan Thee Stallion and Solange. He has won two Grammy Awards, and enjoyed seven nominations. White last featured in Sound On Sound in September 2018, talking about engineering and mixing the album Everything Is Love, by the Carters, aka Beyoncé and Jay‑Z. Four years later White is keen to stress how much has changed since then. As well as mixing the whole of Renaissance, he also has an engineering credit on every song, as well as credits for drum programming and additional production on several tracks.

“When I was younger,” White explains, “I used to be really obsessive about making sure my sessions were well‑organised, with elaborate organisation, proper track names and extensive colour‑coding, and so on. But now I just work quickly, and worry about what really matters. While colour‑coding is helpful, I can simply see from the waveform that I’m dealing with a kick drum or vocal.”

White travels often while recording and mixing, and sets up studios in Airbnbs. “I ship Amphion Two18 monitors with the BassTwo system, and ProAc 100s, and work in Pro Tools HD Native running on a Mac Mini. The system has every plug‑in available, though I tend to work mostly with very basic plug‑ins, nothing fancy. Again, I like to keep it simple. I like to find a house on Airbnb that has a wooden interior because wood resonates really nicely and sounds natural. When I set up a room to work in I take a lot of time to move the speakers around to get the right sound, with the bass sounding as tight and phase‑coherent as possible.

“My setup here is in a bedroom, and I stacked mattresses against the wall on either side of me, to absorb the first reflections. The closet at the back of the room works like a bass trap. I also have some professional acoustic tubes. Downstairs in the living room I have ATC SCM25s with no sub, Genelec 8040s, and a Sonos speaker, combined with a Dangerous Monitor ST controller. The room downstairs is very large, with high, vaulted ceilings, and gives me more of a translation of what things will sound like in the real world. I know many mixers get really uptight about where they work. I used to be one of them, but I just take a ton of care setting up the space and get it done wherever.”

Keep It Raw

When White records Beyoncé, he uses, he says, “a Telefunken ELA M 251 microphone, and I that record through the Avid HD I/O since all my older sessions were done with it and if I have to punch in it will match perfect. That said, I tend to use the Lynx Aurora N converter when I mix on my personal setup. Beyoncé and I both use Audio‑Technica ATH‑M50X headphones when recording.

“There is minimal acoustic treatment when I record and I don’t use a reflection filter, because using a reflection filter means that I can’t see the artist. Typically vocals are performed behind me, and visual communication is important. I also want to make sure the microphone is on‑axis, and that the mic does not move or fall. I need to be able to see what’s happening. I’m recording with one side of the headphones on one ear, and blending and tweaking at the same time. For playback between takes I take the headphones off, and check on the monitors quickly, adjusting anything I feel necessary.

“I used to be really obsessive about the room acoustics when recording, but over the years I have found that most artists just want to get things done anywhere. Sometimes the room I work in is a bit echoey. I do my best to turn off any noisy appliances and focus on setting up my monitors correctly so I have good playback, and I just make it work.

“There’s a song on Renaissance called ‘Pure/Honey’, and I had a tube in the 251 mic going bad during recording. It was noisy, and at first I was like: ‘Fuck, I’m gonna have to use noise reduction software and hope it still sounds right.’ Then I realised that in the context of the song it was kinda cool, so I made it work. When things go wrong, I try to use it to my advantage. Make it sound like it was done on purpose. In this case I added compression, and this brought up the room sound, and I also added some McDSP FutzBox saturation, and it became part of the effect. I just hope to get lucky with things like that.

“When you listen to old records, there are all kinds of flaws everywhere, and I don’t mind that. I like hearing stuff that we would fix nowadays. I think that’s so cool. It’s leaving a little bit of rawness, which can make it more interesting, and play to the emotion of the song. I was listening to some old Wu‑Tang the other night, and it was so raw, it was perfect. If it was mixed like a modern rap or pop record, it’d be ruined. Of course, if something really is wrong, it’s wrong, and a lot of these decisions are genre‑specific. It depends. But if it sounds cool I’ll let it fly. It’s a matter of trusting your taste and ears!

“While I’m recording vocals I’m EQ’ing the drums and the bass and I’m adding delay throws or sculpting the reverbs and delays with EQ, compression, distortion, and modulation. I often heavy‑handedly process stems, because sometimes they sound flat. Horns or strings may be recorded very clean, and I’ll then kind of fuck it up stylistically using the Soundtoys Decapitator, XLN Audio RC‑20 Retro Color, McDSP FutzBox, combined with compression and EQ to fit into the mix while maintaining the feel of the song. I tend to do this when the vocals are being recorded, so it’s all coming together while I’m in the same room as the singer.”

Much of Stuart White’s work is done in Airbnbs, where he takes the time to set up his speaker system to work as well as possible with the room acoustics.

Much of Stuart White’s work is done in Airbnbs, where he takes the time to set up his speaker system to work as well as possible with the room acoustics.

Body Language

White says that he often records and mixes better if something is new to him. “Not yet being too familiar with the track makes it easier for me to do all my broad strokes, get things like EQs and compressors happening, get the low end sorted, and in general get the bulk of the mix happening in the moment. If the kick is not good, fix it now, or get a new one and line that up. That’s the process of the first day, with me trying to get it as close to the end result as possible.

“While I’m editing, adding parts and doing vocals and stacking harmonies, I’m thinking all the time, ‘Don’t wait, get it done now, now, now.’ I’m final mixing it in my mind as I’m going. It’s impossible to do it every time like that, but honestly I put pressure on myself to make it sound good immediately, so that if they said, ‘Let’s put it out tonight,’ it could be done without me stressing it too hard.”

An obvious additional advantage of trying to get as much possible done in one day is that White gets immediate feedback from Beyoncé. “She is a true genius at producing and she’s brilliantly right on it, all the time. She may say, ‘That sounds cool, but can you dirty it up?’ and I’ll put on some of her favourite saturation or distortion plug‑ins to try to get the right feeling. We have very similar taste in sonics and we’re always painting in the sense that there’s a focal point — the lead vocals, the drums, the bass, the chords, all the stuff that’s the meat of the track — and then we’ve got all these sounds that are more in the distance, as in ‘Let’s make this sound like it’s down a long hallway, or in a fishbowl.’

“I work closely with her in terms of where stuff goes in a 3D space. This is where my EQ/saturation/compression skills really come into play, making sure the focal point is always correct. When I mix I like to think about how I can help the emotion come through better, and how to help tell the story. Not to mention that if I can support the emotion and mix fast in the moment, the artist can feel the song better while they are writing and performing it.

“Most of the vocal effects on the songs also go on during that first day. However, the feedback usually is more feeling‑based. It’s the same with most artists that I’ve worked with in my life. They don’t tend to speak in technical terms about EQs and compressors. They talk more about texture, feel and emotion. Some people may use terms like ‘ethereal’ or ‘velvety’. They might say something is too compressed, but it’s just too quiet or EQ’ed wrong. The new generation is quite technical, but actually, I almost prefer it when people give me abstract notes or feedback. It challenges me and gives me energy. As a mixer knowing how to fix something fast is so crucial. So you check your ego and trust the artist.

“Also, when you work with people in the room, you can sense by their body language whether they like something or not. They don’t even have to tell you. I can tell by looking from the corner of my eye whether they are really feeling something. I always make mental notes of the reactions of everyone in the room. If the song switches and people stop moving you know something wasn’t quite right in that spot. I write notes, and go back later and see what threw them off. People won’t always tell me, ‘Oh, that doesn’t feel quite right.’ Being a good engineer and mixer is not only about being sensitive to the music, but also about observing people — without staring at them! — and how they’re feeling when they’re listening.”

In Your Face

Other aspects of Stuart White’s mixing approach have changed in recent years, too. “I’m mixing a bit more aggressively than I did in the past. I used to try to mix a lot warmer back in the day, but now I like being crisp and in your face. Not harsh, but just a little more sizzly and exciting I guess. It depends what you’re aiming for. If it feels right dialled in clean and not aggressive, then go for it. Certain songs call for that, and certain songs don’t. I like having something aggressive against something clean because it creates depth and contrast.

“It’s also understanding genre. I’m a big genre fan, I love knowing different genres and how to blur them. Like sometimes I might want the low end 808 of a rap record combined with a saturated live bass of a punk record, with the top end of a modern pop/R&B record combined with some effects from an EDM record. When you’re recording a song from scratch and you’re making all those decisions while it’s happening, mixing is more of an extension of the production.

“The mix of ‘I’m That Girl’ helps turn the song into a crescendo. The intensity of the song builds, as does the intensity of her vocals. To me it’s really exciting. When you listen to that mix loud, you can really feel it push. Having things sound dynamic is cool. Loudness and excitement are closely linked, and for this reason many people mix with a bunch of compressors on the master bus. However, these days I work with nothing on the master bus. I found out that I can get things way louder and more natural‑sounding like that. It’s about creating a fat crest factor of a waveform, and if you’re listening to a limiter or compressor all day long, you boost one frequency it could turn something else down. You can really hear what you’re doing when you work with nothing on the stereo bus. I highly encourage young engineers to learn to work this way.”

Stuart White: While I’m editing, adding parts and doing vocals and stacking harmonies, I’m thinking all the time, ‘Don’t wait, get it done now, now, now.’ I’m final mixing it in my mind as I’m going.

Headroom Is Everything

Not only does White not have a compressor or limiter on his master bus, but he also makes sure that his mixes go nowhere near 0dBFS. “I’m working with 6 to 10 dB of headroom on my master fader the whole time, both when recording and 90 percent of mixing. A huge part of the way I work is that I never want to hear the ceiling being hit. I don’t want to hear a limiter kick in, I don’t want to hear a compressor pumping on the mix unless it’s a stylistic choice.

“This forces me to dial in all sounds as fast as possible. Also, sometimes when I’m nearly finished, and the artist asks to ‘add a new 808’, or ‘add this new sub‑heavy drum’, it means I have headroom left. I’ve been in that tricky situation when you have to add a bass‑heavy sound to a finished mix, the headroom is maxed, and you have to create headroom for the new sounds. It’s a bad feeling. I came up with workarounds back in the day using aux tracks and master faders but now I simply always make sure I have enough headroom even when the mix is ‘done’ because I never know when we might add something. It gives you the ability to push, you can ride things creating crescendos. It’s good to work this way because my kick is not going to push down the 808, and the kick and 808 are never going to take the vocal down.

“To make sure I can do this, I set my headroom right at the beginning. I have designated how loud the kick and the bass and everything can be. I also have master faders and aux tracks that I can pull back at any time. So if the artist wants to hear her vocal louder I can turn it up. I never risk Pro Tools clipping, which is something that drives me crazy if it happens.

“Another advantage is that it allows me to really shape the transients. I’m all about crafting the transients, whether that means taking the transient off one sound to leave space for another, or thinking, ‘Do I want the esses in the vocals to occupy that frequency, or the top end of the hi‑hat, cymbals, or synth to take that space?’ This is always on my mind. This also goes for the kick, 808, and bass synth relationship. I balance transients, not just frequencies. In the case of ‘I’m That Girl’, I wanted her vocal to always be in your face, and the transients of her esses to jump out a little bit at times. I try to shape the transients in a way that that’s exciting and because I don’t have a limiter on the master bus I can hear exactly what I got.”

Stuart White’s own studio in LA is called Avenue A Studios West.

Stuart White’s own studio in LA is called Avenue A Studios West.

Balancing Point

Like everyone, White in the end has to deal with the realities of the market place, and make sure his mixes are loud enough to be competitive. He has several solutions for this. “First of all, as I mentioned, I get things to sound louder and more natural when I’m not working with a limiter on at first. In the old days people weren’t mixing with all this stuff on the master bus. It’s a current trend to do it, because people think they need it in order to get a loud mix. But if you want to get loud and dynamic it’s about balance. I balance better when I work the sounds without limiting from the beginning. If you want to take one thing away from this article, this is it.

“So I get my mix to sound balanced and exciting and I get everything to sit together EQ‑wise and transient‑wise, and I print my harmonics and saturation treatments, and so on. Then, at the end of the night, I put the original AOM Invisible Limiter on the master bus, and I listen for a while, and I make some adjustments. When I put that limiter on at the end of the process, it doesn’t kill the transients. And IMHO if you balance a mix very well you can make it loud easily.

“I put the Invisible Limiter on at 8x or 16x oversampling while using the unity gain/bypass feature — make sure you take this off when you print — while metering with the Waves WLM Loudness Meter, and if I have balanced everything correctly I can hit it hard with no distortion, major loss of transient detail, or performance dynamics. If I can’t hit it hard yet because I hear distortion or pumping I go back into the mix and figure out what’s eating up the headroom and fix it fast.

“The Invisible Limiter doesn’t change the colour of what I did EQ‑wise and tone‑wise. It’s the cleanest, most transparent limiter I’ve ever heard, whereas the many other limiters on the market change the tonality a lot. It was always a frustrating process for me, because when I tried to work without limiting, and then I added one at the end, it would sound too different. The Invisible Limiter doesn’t really do that. Usually I can hit ‑7 LUFS on a mix easily with it, and things don’t sound choked. I add the Invisible Limiter for reference mixes only. However, for mastering I send the unlimited version of my mix to Colin Leonard. He uses my Invisible Limiter‑treated mix as a reference, and then beats it slightly.”

Too Much Mixing?

For Stuart White, the roles of engineer and mixer have always been on a continuum, and lately they appear to be rolling more and more into one. In some ways, it’s a return to a bygone age, and it helps to avoid one of the big pitfalls that all mix engineers encounter in the DAW age. “The beauty of tracking engineers also doing the final mix is that it’s easier for them to stay connected to the initial feeling. It’s how engineering used to be, back in the day, when whoever tracked also mixed. Of course, I go back and tweak the mixes afterwards. But that first day is when the feeling is in the air.

“When I go in later to refine things that need refining, I make sure I’m not neutering the feeling out of something and that I am not over‑mixing it. I feel that many things today are over‑mixed. We have all these tools, all this CPU power, all these multiband compressors, active EQs, and we can go crazy with it. And sometimes they are incredibly useful; and I definitely use them, with care. Sometimes I look at my vocal chains and I’m like, ‘Oh that’s a lot of plug‑ins.’ But I make it sound like it’s not EQ’ed. Even if you have all this stuff on there, you need to make sure it doesn’t sound overdone. It simply has to sound the way it should sound.

“The tell‑tale signs of over‑mixing are phase issues, bad separation, or that you don’t feel the dynamics any more. You don’t hear the singer pushing and he or she does not get louder. Everything is static. No frequency gets unruly and nothing bites your ear. I’ll definitely notch out some 3kHz in a vocal that sounds too harsh. I do that all the time. But you can really overdo that if you’re not careful. You can overcook it to the point that everything is so perfectly dialled in that it takes the life out of a mix. So it’s about knowing when and where to do something, and when not. And again, when I’m emotionally connected with something, I’ll have more fun with it and I’ll be able to work quicker, get the ideas happening faster, and do stuff in ways that are more exciting.”