The new album by Noah Lennox, aka Panda Bear, features familiar collaborators pulling in a very different musical direction.

Noah Lennox overdubs a vocal at Josh Dibb’s Rabbit Hole Studio in Baltimore.American‑born, Portugal‑based artist Noah Lennox has found enduring popularity in the world of electronic music, both as part of Animal Collective and as a solo artist under the name Panda Bear. New album Sinister Grift is his sixth under the latter name, and sees him backed by something surprisingly close to conventional rock arrangements. And although it’s very much a Panda Bear record, Sinister Grift features contributions from the other three members of Animal Collective: Dave Portner (Avey Tare), Brian Weitz (Geologist) and Josh Dibb (Deakin), and was co‑produced and mixed by veteran Panda Bear and Animal Collective collaborator Josh Dibb.

Noah Lennox overdubs a vocal at Josh Dibb’s Rabbit Hole Studio in Baltimore.American‑born, Portugal‑based artist Noah Lennox has found enduring popularity in the world of electronic music, both as part of Animal Collective and as a solo artist under the name Panda Bear. New album Sinister Grift is his sixth under the latter name, and sees him backed by something surprisingly close to conventional rock arrangements. And although it’s very much a Panda Bear record, Sinister Grift features contributions from the other three members of Animal Collective: Dave Portner (Avey Tare), Brian Weitz (Geologist) and Josh Dibb (Deakin), and was co‑produced and mixed by veteran Panda Bear and Animal Collective collaborator Josh Dibb.

Dibb, it turns out, had been enlisted by Lennox before there was even an album to be mixed. “During the pandemic we decided to record a record remotely, which became [2022’s] Time Skiffs,” he remembers. “Noah had been recording his own drums. Everybody probably does this, but I will often start to ‘pre‑mix’ things, just to help them make sense to me. Noah was responding really well to what I’d done, and he had even suggested he’d be up for me mixing the record. We all talked about it and ultimately the band felt like that wasn’t the right move. But he said, ‘Well, I want you to do my next record.’ And I was like, ‘Dude, thank you. But you have no record right now!’ But, lo and behold: years later, he stuck to it.”

Unbeknownst to Dibb, an album was indeed taking shape. “I got an offer to do a festival in Madrid, pre‑pandemic,” explains Lennox. “I thought it would be exciting to play all‑new music. So I wrote five, maybe six songs for that. Most of them appear on this album in some form.

“I had the idea to do some straight‑ahead recordings of bass, drums, guitar and singing. I would play everything, and then we would, kind of, abstract those songs into something else. But after recording everything, we just really liked them the way they were. So that idea faded away, and this sort of rock band thing kept going! That’s how I find a lot of stuff happens: there’ll be maybe 10 different ideas I’ll have that hover around for a while, and some of them will go away, some of them grow into other things. And maybe two or three you can trace from the very beginning all the way to the end.”

Camping Out

was co‑produced and mixed by veteran Panda Bear and Animal Collective collaborator Josh Dibb.

was co‑produced and mixed by veteran Panda Bear and Animal Collective collaborator Josh Dibb.

The decision was made to record Sinister Grift at Lennox’s own Estudio Campo in Lisbon: by his own admission a modest space, but no less than what was needed. “I just wanted a room,” he explains. “It has a big kind of booth, where you can put a drum kit — which we did — and a control room. I have a pair of ATC monitors, a UAD Apollo interface, a two‑channel Neve preamp, a Drawmer compressor, and that’s pretty much it. I don’t have a lot of outboard stuff. This was the first kind of ‘big project’ that we did there. And Josh was the first person I ever started recording stuff with, so it felt like a closing of the circle, in a way. I was really excited to do it with him.”

For Dibb, the decision to record in Portugal presented a daunting but exciting set of challenges. “I was trying to figure out how much stuff it would make sense for me to fly over with,” he remembers. “Noah had some [Shure] SM57s there, an [Shure] SM7B... I had also convinced him to get some Coles 4038s when we were tracking Time Skiffs. He is quite gear‑resistant in that way! He’ll pick certain things now and again, though, like his ATC monitors in the studio. It didn’t seem cost‑effective for me to fly over with multiple cases, so he sent me a list of mics and preamps and stuff that he could get if needed, and I gave him a wish list based on that. What we ended up with was great. We made it work.”

The first sessions for Sinister Grift took place at Lennox’s own Estudio Campo.

The first sessions for Sinister Grift took place at Lennox’s own Estudio Campo.

Work began in November 2023, with a streamlined and light‑footed approach to recording. “We would jump around, day to day,” says Dibb. “I’d have mics up on the kit, but then I’d have to move them to another room to do percussion, and then move them back to the kit... I don’t want to overemphasise the jankiness of it; most of the records that I’ve done, Dave [Portner]’s records, too, they’re often like that. They almost feel closer to home recording. So I get into the vibe of that. There’s something beautiful, I think, in getting to the point where you’re like, ‘Well, these are the limitations of what we have to work with, and we’re going to make it work.’”

Guitar Music

Sinister Grift is the sixth Panda Bear album.

Sinister Grift is the sixth Panda Bear album.

“I wanted to do something that was rock,” says Lennox, “but, really early rock. The [2015’s] Panda Bear Meets The Grim Reaper, [2019’s] Buoys era — I guess that was, like, computer music, really. For this, it was early rock; that’s the kind of stuff that was really resonating with me. Fender had given me an Acoustasonic. We used that a bit, and then also, actually, my dad’s old guitar. A red Stratocaster. I’m very much like, whatever is around: I’ll just use that! I’m not super picky.”

“A lot of the stuff that I brought was pedals,” remembers Josh Dibb. “I brought a pretty hefty case of pedals! Noah had told me some sort of touchstone sounds he wanted, like distortion: that played a bigger role in this record than it has in other records. He had an Elektron Analog Drive, usually on the front end of his guitar, but he didn’t have any amps. Initially I was like, ‘Hey, man. It’d be cool to have an amp...’ But that ended up becoming a thing. We recorded all the bass and the guitars direct and would work it out later down the line.

“I did re‑amp some stuff in the end, I have a [Fender] Twin in my studio and a Music Man. But honestly, for a lot of it, I just was shaping the direct sound. I’d split his guitar at the front end and track one guitar performance with three different signals: there’d be like a completely DI’ed signal, there’d be the mono drive signal, and then there would oftentimes be another stereo signal that could either be foundational to the song, or be more like a wash in the background. So there’s times in the record where it feels like we must have tracked like three things on top of each other, but it’s actually just one performance.”

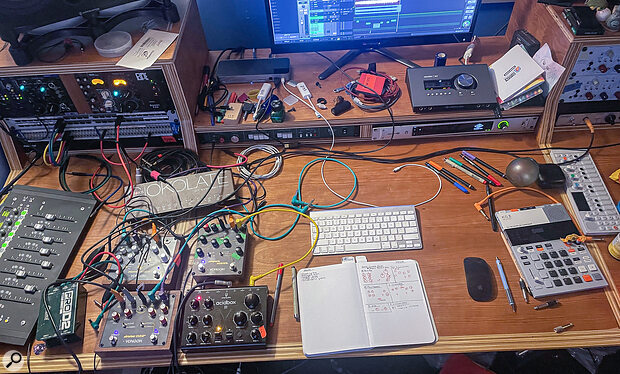

Distortion and spatial effects would both come to play a key role in the album’s sound, be they boutique, vintage or modern. “There’s one pedal company, Vongon, who make some really beautiful pedals,” Dibb continues. “They have a reverb and vibrato pedal called an Ultrasheer, and you can switch the order of the two effects. So sometimes the reverb goes through the vibrato, which is a very different sound. We also borrowed a bunch of different distortion and fuzz pedals from Pete [Kember, aka Sonic Boom] and we cycled through those to find the right tone for different songs. We used the [Hologram] Microcosm as well; although that pedal I have a very love‑hate relationship with. It’s almost too easy. You turn it on and it’s instantly such a vibe! Also the [Hologram] Chroma Console — that became a huge part of it, although more in the mixing phase, I think. They weren’t out yet when we were recording, but by the time I got back to the States, a buddy of mine told me to check it out. I think Noah is now using it for playing live.”

Effects pedals, mostly supplied by Josh Dibb, were central to the sound of the album.

Effects pedals, mostly supplied by Josh Dibb, were central to the sound of the album.

Noises On

The contributions of Animal Collective’s other members were varied. “‘Ends Meet’ has a Dave [Portner aka Avey Tare] noise solo,” Lennox notes. “I have no idea how he made it. I just said, ‘Give me a noise solo here!’ Two days later, it came back.”

Meanwhile, Brian Weitz, aka Geologist, had compiled a bespoke sample pack at Lennox’s request. “I asked Brian to make a big sound pack,” he explains. “I had that before we even went into the studio. There’s something called Playbox that Native Instruments make. It’s a sort of matrix that you can pump your own samples into, but they’re all divided up into different sections: synths, voices, basses, noises... maybe five or six categories. I asked him to do me packs of all those, because I was planning on using that, but then we just wound up using them as audio files. I would drag them in, and we would see if we could sort them out.

“A lot of his stuff appears on the songs, little bits here and there. There’s a song called ‘Elegy For Noah Lou’ towards the end of the album, which we wove a whole bunch of his sounds behind. That one is sort of like a live take, where I was playing guitar and Josh was tweaking a table of effects that the guitar was running through, and then we kind of wove Brian’s sounds around that take.”

Where, then, is the line between collaborating as individuals and collaborating as Animal Collective? “I don’t think there really is one,” replies Lennox. “At least, I’d prefer there not to be. It really feels less interesting to completely separate the two. One thing always bleeds into the next, so they all kind of feel part of the same creative wave to me. So there is no line, for me. It might sound lofty or corny, but I try to make sure that whatever is best for the song is most important. Everything else should be secondary to that. Like, the solo on ‘Ends Meet’. I knew I wouldn’t do it as well as Dave would, so I asked him to do it.”

Split & Recombine

Having finished the lion’s share of tracking in Lisbon in late 2023, Dibb and Lennox separated to continue working on the album individually, before reuniting the following March for further recording and post‑production. This was to take place in Baltimore; firstly at Dibb’s own studio, Rabbit Hole, and subsequently at the larger, SSL‑furnished Wright Way. “After we did the main recordings, I did kind of a whole run of stuff with a [Sequential] Prophet‑5,” remembers Lennox, “just kind of going through every song. I spent a couple of weeks, just making little parts anywhere I thought a song needed something.”

Mixing took place at Wright Way Studio.

Mixing took place at Wright Way Studio.

Dibb was similarly diligent during the interim. “I spent something like two‑and‑a‑half months working on things before Noah came to the States for further production,” he says. “But the overall shape of stuff was more or less established by the time we left the tracking session. I recorded some piano stuff, the horn arrangements on ‘Ferry Lady’... that was stuff I wrote while we were away, and would send to him to see what he thought. Some of the guitar effects were locked in when we were tracking, but some of them didn’t land, so I had to reimagine them or try different things. That’s where having that original DI performance was really helpful.

“It’s like a two steps forward, one step back kind of thing. You know, a mixing choice can become a production choice — you might decide to do some further processing on some fundamental element — and it might shift the entire feeling of what’s going on. I’ve observed other engineers who really differentiate tracking from production from mixing; those are three very separate stages for them. I have a very hard time doing that. I’m looking for vibe.

“For me, the moment something is tracked, it’s like, ‘Does this feel right?’ It’s usually pretty hard for me just to say, ‘Oh yeah, we’ve recorded the snare decently. It’ll be fine.’ I want to make sure of the sound we’re getting: sometimes that is just about mics in the room and the way that it sounds, but oftentimes it’s about additional processing. In tracking, I was immediately starting to add reverbs, add effects, tremolos, distortion, delays, like all sorts of stuff to try and get things into the space that I knew we were aiming for. And in a lot of cases, a lot of that stuff did hold all the way to the end.”

Finally, stems were mixed down by way of the SSL console at Baltimore’s Wright Way to achieve, in Lennox’s words, “a little grit, a little analogue dust”. Stereo subgroups were stemmed through the console and selectively processed through the studio’s vintage outboard gear — a vintage API 560 EQ or two, a UREI 1178 compressor where needed.

Josh Dibb: I’ve observed other engineers who really differentiate tracking from production from mixing; those are three very separate stages for them. I have a very hard time doing that. I’m looking for vibe.

“Paul Mercer at Wright Way, he is obsessed with transformers!” says Dibb. “He had made a three‑channel transformer bus box, which basically the entire mix can run through. And you can switch between different transformer types. That transformer box was a huge part of it. We would just flip through the different options until we found one we liked — that would usually put a curve on the low end. We had done so much fine‑tuning of the mixes already at that point. It was really more about just stepping back and hearing the warmth, seeing how the low end would really come to life.”

Shared Excitement

Thanks to the involvement of Josh Dibb and Lennox’s bandmates, Sinister Grift is the latest flowering of creative relationships that have stood the test of decades. “We started working with multitrack cassette stuff together when we were maybe 13 years old,” says Dibb. “That’s how we spent our weekends, we would mess around. And this, in many ways, feels the same. Really, nothing has changed. You know, it sounds like a funny way to put it, but I’ve been really grateful for that. There were moments where I was like, ‘God, I could really fuck this up.’ With Noah, if something’s bothering him — or if there’s something he’s feeling really good about — he’ll let me know. But he allows a lot of space to mess around.”

Noah Lennox, in fact, says that creative gratification comes as much from generating enthusiasm in those around him as it does from within. “Part of the impetus for getting a lot of people involved is, I like to make other people feel excited about doing the thing,” he says. “I get more excited to see somebody else get really jazzed up. I feel like that drives me, more than my own contentment. It feels more fun.”

The Singing Panda

A distinctive element that consistently shines through Panda Bear’s output, and Noah Lennox’s numerous guest appearances, is his signature vocal delivery. Needless to say, the right choice of microphone was critical. “Most of the lead vocals we did through a Soyuz 017,” says Josh Dibb. “I do think Noah felt like he’d finally found his mic. I think he has gotten one for himself, too. Hearing himself back, even while tracking, it just felt really good to him. And I agreed.

“Noah has such a beautiful voice, so much clarity. But at the same time there is something very particular that’s needed. I think that that mic just brought out the precision of his voice, but with enough gentleness at the same time. It’s so smooth.”

The 017 wasn’t the only mic in play, however. “There were some songs where I knew I wanted to use the SM7B instead,” continues Dibb. “Where I just wanted that kind of mid‑forward, focused kind of sound. And then some songs where I knew I wanted the 017 for that more open sound. On one occasion I ended up using a blend of the of the two: I felt like there was something I could get from the push of the SM7B, that wasn’t quite coming through in the 017. That kind of crunch in the vocals, a bit of distress already in the mic signal.”