Jean‑Michel Jarre in the immersive studio at the Paris headquarters of Radio France.

Jean‑Michel Jarre in the immersive studio at the Paris headquarters of Radio France.

Immersive audio is helping Jean‑Michel Jarre implement a distinctly French musical vision, inspired by his own mentors.

“I feel very privileged to have witnessed three moments of disruption,” says Jean‑Michel Jarre. “One was the emergence of electronic instruments. The second was the emergence of computers and the digital age. And the third, which is maybe the most important one for me, is the technology of immersive worlds.

“For a human being, the feeling of immersion is first of all audio, before being visual. The visual field is 140 degrees. The audio field is 360 degrees. So for the development of the metaverse, the development of XR and VR, sound is absolutely crucial. And I think musicians have a lot to say and to do in virtual worlds.”

For Jarre, immersive audio is not merely an extension of stereo, or a superior way of repackaging content originally created for stereo. It’s a much more radical medium, with endless possibilities that musicians are only beginning to get to grips with. “Stereo is an illusion. [Film director] Christopher Nolan used to say that he loves 2D, rather than 3D with glasses, because he loves to control the illusion of perspective. It’s what great painters have done in the history of painting. And in music, it is the same. With stereo and with a frontal approach, with a flat 2D approach, we have been trained as musicians to create perspectives, to create layers. Suddenly, with immersive audio, you take this and you put them all around your ears.

“So it’s actually, in a way, going back to the natural way of listening to sound. Because in nature, stereo doesn’t exist. The world around us is mono, and it’s only our environment and our ears which are creating the perspective in audio. I think the music of the future is going to be absolutely different because of that. In a few years from now, and especially also because of the development of the metaverse and immersive worlds, our children or grandchildren will regard stereo as we regard the gramophones of our ancestors.”

Jean-Michel Jarre: "For a human being, the feeling of immersion is first of all audio, before being visual. The visual field is 140 degrees. The audio field is 360 degrees... sound is absolutely crucial. And I think musicians have a lot to say and to do in virtual worlds."

Centralisation

The technology that powers Jarre’s immersive project, Oxymore, is new, but the philosophy behind it is not. From 1969, Jarre trained under French composers Pierre Henry and Pierre Schaeffer. Both were pioneers of musique concrète, and both sought to break down conventional perspectives in music performance. “These pioneers defined a new vocabulary. They were breaking the tradition, not only by considering music in terms of sounds, and saying every noise can become music, depending on the intention of the musician, but also in terms of space, saying, ‘OK, the sounds should be 360 degrees.’ They were not interested by stereo at all.

“They were really obsessed by this idea of 360‑degree composition: at that time, by just creating sounds for each speaker, and not so much in terms of movement, because the technology was not there, but with the idea of creating a kind of immersive platform from which they could explore textures. They were really thinking of multi‑mono, placing speakers in circles and then using a console to place a sound here and there. It was very basic, but the idea was to break with this idea of the frontal relationship with the sounds. And they also created, later on, what they called the Acousmonium, which is an orchestra of speakers on stage.”

In his own experiments with 3D composition and mixing, however, Jarre formed the view that today’s most popular spatial audio formats aren’t yet truly ‘immersive’, in the sense of giving equal status to sound arriving from all directions. “I realised at quite an early stage, even before this project, that Dolby Atmos is an excellent system, but originally created for movies and not for music. And then we had to, as musicians, adapt ourselves to a technology that has not been devised and created for us. In the history of music, we are quite used to this. But it creates a lot of issues, mainly for binaural because of the different filters.

“Dolby developed their system with a kind of ‘heliocentric’ approach that was basically made for movie theatres. Wherever you are, you are in the right position to have the dialogue in front of you and the rest of it on each side and the effects behind. And that is not at all what we need as musicians. We are more ‘egocentric’ as musicians, and we need to have an equivalence all around us from the centre point. It’s quite a different approach.”

For this reason, Oxymore was mixed not on a conventional Atmos system, but in an experimental studio at the Paris headquarters of Radio France, using Steinberg’s Nuendo and L‑Acoustics’ L‑Isa to feed a monitoring system with 29 loudspeakers. It was a fitting choice of location: Jarre’s studies with Henry and Schaeffer took place in this same building, and he used to sneak into unused studios at night to practise his craft.

The Radio France immersive studio features 29 Genelec monitors arranged in three layers, with Steinberg’s Nuendo controlled from a Yamaha Nuage fader surface.

The Radio France immersive studio features 29 Genelec monitors arranged in three layers, with Steinberg’s Nuendo controlled from a Yamaha Nuage fader surface.

The Concrete Jungle

In tribute to his mentors, Jean‑Michel Jarre used the techniques of musique concrète extensively in the creation of Oxymore. In fact, the seed of the project was a cache of sounds created by Pierre Henry himself, which were passed to Jarre by Henry’s widow after the composer’s death in 2017.

“In the middle of the 20th Century, these guys were really obsessed by the textures of sounds. I studied this with them. Schaeffer classified almost all sounds of nature by types of textures. I think in electronic music, texture is fundamental — and these days we are forgetting it, because we have so many plug‑ins and so many ready‑made sounds that we are not really working on the textures any more. And for Oxymore, I really tried to work on acoustic sounds or electronic sounds to merge them so after a while, you don’t know if it’s a digital sound or a sampled sound any more. That was the link with Pierre Henry, because it has been really useful for me to use — not so many of his sounds, but some of them — but more as a source of inspiration.”

Discussions of musique concrète often focus on the use of tape loops, but Jarre does not think the specific medium is very important. “For me, tape is secondary in the idea of musique concrète. What is important is the word ‘concrete’, which could be the opposite of abstract: the texture, the content of sounds. To use noises and transform them into musical elements. When Pierre Schaeffer and Pierre Henry started to work on musique concrète, it was actually before tapes. They were using 78s, and the first concert they did was exactly like what a DJ used to do 20 years ago. They had actually a bunch of 60 or 80 78s — not vinyls, it was like metallic plates — and they were playing them, slowing them down, playing them in reverse, exactly like scratching. They are really the first DJs of music history!”

The development of sampling, likewise, made it easier to implement the ideas behind musique concrète, but did not fundamentally change them. “I was very lucky enough to have one of the first Fairlights in Europe. It was like a grail for me because suddenly, what I was doing before with tapes and taking lots of time to do, suddenly you could record the sound of your dog, as we know, and play your dog on the keyboard. So it was a total revolution. But it’s the same approach, in terms of taking sounds and transforming them into musical elements.

“What I wanted to do with Oxymore was not only this, but to go back to what musique concrète is all about, what electro‑acoustic music is all about. Not in a cerebral, intellectual way, but also to have fun. I got some sounds from Pierre Henry, but at the end of the day, I didn’t use them so much. Maybe in the whole album you have five percent of these sounds. But they are very important because for me, they were the source of inspiration for the whole project.

“Beyond a tribute and an homage to Pierre Henry, I love also the idea that musique concrète is quite close to another French movement called surrealism. The Marcel Duchamp approach influenced a lot of musicians such as John Cage: a kind of irony in terms of assembling sounds which have nothing to do with each other. And it’s something that I really enjoyed by doing it. It was like going back to the roots, but with the tools of tomorrow!”

Old & New

Jean‑Michel Jarre has an enormous inventory of instruments at his studio, including practically every synth ever made. He typically selects a smaller palette from within this armoury to provide the core sounds for each project. The palette from which the Oxymore textures were generated was light on classic analogue synths, focusing instead on acoustic instruments as sources for sound design, along with modern digital synths and controllers.

Few analogue synths were used in the creation of Oxymore, but Jarre’s Mellotron does feature. It is an unusual early model with two manuals side by side, designed originally for film dubbing.

Few analogue synths were used in the creation of Oxymore, but Jarre’s Mellotron does feature. It is an unusual early model with two manuals side by side, designed originally for film dubbing.

“I used a palette of instruments, from old Mellotrons to recent keyboards, and also sound effects that I recorded with contact mics, such as the Zeppelin Labs Cortado — for me, one of the best contact mics available. I’m not sponsored, but they’re really cool for what we need as musicians. I use lots of elements that people use when they’re doing sound effects for movies, and old instruments such as the Cristal Baschet [see 'The Cristal Baschet' box later on].

“Two very recent instruments are the Expressive E Osmose and the Nonlinear Labs C15. The Osmose is an amazing instrument, because you can really have so many ways of processing the colour and the pitch and all that. You can move horizontally, vertically, the speed and everything, so it was an ideal instrument for what I needed, to work constantly on the speed of a pitch or the evolution of sounds. I really used it a lot for having evolving textures and sounds. And it’s interesting because these instruments are very, very new.

Modern instruments that featured heavily included the Nonlinear Labs C15 and the Expressive E Osmose (below, lower right in front of modular).

Modern instruments that featured heavily included the Nonlinear Labs C15 and the Expressive E Osmose (below, lower right in front of modular).

“I use also, for performance, the Erae Touch [MPE controller], from Embodme. And also some plug‑ins, of course, from Arturia and Sample Logic. You have so many. And Spitfire also. I use a bit of Omnisphere also. A mixture of different digital elements, and I use a lot of granular processing, which you can do with lots of gear these days. Granular synthesis was also part of this work on making a sound evolve, even sounds that I recorded.

Many of the sounds on Oxymore began life as recordings of acoustic instruments such as the waterphone (front) and thunder drum (rear), often miked with contact microphones.“I have a few different waterphones, from a fantastic craftsman from Poland, Janus Slawek. The waterphone is an instrument you play with a bow. You can put some water in it, and then by moving it while you play with the bow, you can create some very interesting Doppler effects. So I use that a lot. I have a few. And also, the thunder drum is a quite interesting drum with a long metallic tail, and by moving it, you create really the sound of thunder — but it’s not thunder. As Fellini, the Italian director, has always said, ‘I’m not interested by the sound of the sea. I’m interested by the image of the sea. I like to recreate my sea in the studio with some cloth and paintings and fans, and doing something which would be my image of the sea.’ It’s a little bit the same with these thunder drums. You create your own thunder, which is of course not the same one as the real one.

Many of the sounds on Oxymore began life as recordings of acoustic instruments such as the waterphone (front) and thunder drum (rear), often miked with contact microphones.“I have a few different waterphones, from a fantastic craftsman from Poland, Janus Slawek. The waterphone is an instrument you play with a bow. You can put some water in it, and then by moving it while you play with the bow, you can create some very interesting Doppler effects. So I use that a lot. I have a few. And also, the thunder drum is a quite interesting drum with a long metallic tail, and by moving it, you create really the sound of thunder — but it’s not thunder. As Fellini, the Italian director, has always said, ‘I’m not interested by the sound of the sea. I’m interested by the image of the sea. I like to recreate my sea in the studio with some cloth and paintings and fans, and doing something which would be my image of the sea.’ It’s a little bit the same with these thunder drums. You create your own thunder, which is of course not the same one as the real one.

“And also, there is another percussion element called the ocean drum. It’s a flat drum with two skins, and then you have a few hundred little lead balls between them. This is also a very nice instrument that I used, not necessarily to recreate the sound of the ocean at all, but to create this evolving noisy effect that you can only have with the microphone and contact mic, which is different from white noise or pink noise.”

In The Round

The process of creating musique concrète textures went hand in hand with that of juxtaposing them in space and time. Jarre composed immersively from the very start, using a 7.1 Genelec surround rig in his own studio. “I forced myself not to be too much in the front, to have a different approach. Otherwise, I realised that I could fall very easily into the trap of: OK, we are so used to working with two speakers in front of you. Then after a while, the basic part of the track is in front of you, and then you put some effects around — and then you go back to what I’ll call the Dolby trap — with lots of respect with Dolby, because they give us at least a tool we can use to place these objects in space.

“And also, because I was not always working in 5.1 or 7.1 here in my own studio, I kept some extreme movement in stereo by saying, ‘That’s going to be interesting in the final spatialisation, not only to deal only with mono sources, but also a mixture between mono sources and pre‑spatialisation in stereo I could put somewhere, to create this kind of fusion in space.’ And I think that worked quite well.

“I didn’t start with melodies,” says Jarre of the composition process. “The melodic parts for me were not crucial and happened later on, almost like a cherry on the cake. But basically, I wanted to create the sonic environment, and the elements in space. That was really the biggest challenge: how to create this fusion between the high frequencies and the low mids, in space. So I really started by trying to create a kind of palette or range of sounds that could work together in space, but keeping dynamics.

“I also didn’t start, like in lots of electronic pieces or songs, with the beats. I started with other parts, and then I tried to inject the drums and the bass afterwards to see how I could deal with this. And most of the time I tried to put them in a cross shape [within the 3D soundstage], or sometimes just keeping them in stereo because it was better. But I tried to mix all the drums and bass in at an early stage to see how it worked with space.

“I had lots of fun changing tempos completely, experimenting with the speed and the bpm, and I used lots of tempo changes within the textures and sounds themselves. Lots of bending the sounds, and if it was not coming from a synth, I used the transposition variations a lot [ie. changing pitch without correcting the tempo].

“Western music is based on harmony, whatever we do. If we’re doing hip‑hop or rap, it’s still there. So it’s always been there, all along the project. I forced myself not to start with the harmonic approach, but at the end of the day, I was using sounds and these sounds were fixing the harmony or the pitch somehow. I liked not starting with simple melodies and doing the arrangement, thinking I was doing the reverse, but probably the harmony was present even at the beginning.”

Jarre’s studio just outside Paris has two main spaces. This is the more conventional studio room, equipped with an SSL console and a 7.1 Genelec speaker system.

Jarre’s studio just outside Paris has two main spaces. This is the more conventional studio room, equipped with an SSL console and a 7.1 Genelec speaker system.

Immersive Mixing

Once the material had been assembled, the pieces that make up Oxymore were mixed in the immersive studio at Radio France. This involved transferring the audio from Ableton Live to Steinberg Nuendo, and using L‑Acoustics’ L‑Isa system to develop initial panning and motion that had been carried out at the composition stage. “On Max For Live, you have some very interesting tools that I use. But otherwise, by far, Nuendo is the best at the moment, the most advanced DAW for multi‑channel, even more than Pro Tools. Nuendo has really developed that, and I really hope that Ableton Live is going to develop more multi‑channel technology in the future.

“We kept a lot of my early pannings, but then we put them in L‑Isa and then fine‑tuned them or recreated new ones. But one of the secrets or the secret of multi‑channel is that you need much more audio material than you do for stereo. I always thought that ‘less is more’ should be a motto for all of us, but in the case of multi‑channel, more is more. We need to have lots of textures and elements to play with, constantly.

“In the case of Oxymore, what I tried to do is think in terms of placing objects in the weightlessness of space, where you could put objects all around you. And from the beginning, to try to find a fusion between these elements. Because the big difficulty in a multi‑channel format compared to stereo is that once you start to separate the elements in space, you lose the fusion which is essentially music, especially in the bass and the low mid. It’s like a symphony orchestra. You write for a symphony orchestra. If suddenly you separate the violins from the percussion, from the winds, from the brass, you lose the magic of the music.

“And what is fantastic for the musician is actually, most of the time when you have to deal with a stereo mix, you have to fight against the side‑chains and things to give space to everyone. In 360 degrees, in multi‑channel, you don’t have that because everything can be heard on its own. So that’s the luxury. It can be a trap. It is also something that is very, very interesting for a musician, because you can put many more elements at the same time. And I think, I hope, that people will feel that in Oxymore, you have a kind of richness in terms of variety of elements, because 360 allows you to do it.”

One of the things that Jarre and Radio France engineer Hervé Déjardin like about the L‑Isa system is that panning is angular rather than coordinate‑based, as it is in many DAW surround panners. “We put everything in the L‑Isa system, which allows you to pan objects through 360 degrees, degree by degree. But then you have to deal with the Apple renderer and the 7.1.4, the existing format for the audience. You have to simplify it through Dolby Atmos to have a format able to be heard by the audience.”

Jean‑Michel Jarre: "It was like going back to the roots, but with the tools of tomorrow!"

Binaural Trouble

This, says Jarre, works well enough on a typical 7.1.4 loudspeaker system. But the binaural render is another matter. Many streaming services create the binaural version as an automated fold‑down from the surround mix, with little or no control available to the artist and engineer — and he feels that the results are often less good than the orthodox stereo mix. “The Apple renderer is not exactly the same as the pure Dolby Atmos renderer. So it means that if you want to really be effective for Apple, you have actually to produce a special file for Dolby. And then you have the Fraunhofer European system, which is absolutely, in my opinion, the best, but they still have also the same kind of issues with the filters of transfer [head‑related transfer functions] for Sony 360, which is again different. So we are in a stage at the moment where if you want to be efficient and to be good in each of these different profiles, we have almost to produce a master and a mix for each of those profiles.

“At the moment, we don’t have mastering rooms for multi‑channels or binaural, but as soon as you want to have a proper result for binaural, you need to go through a mastering stage. And this is also something which, in comparison to stereo, is still a problem, because suddenly when you go from a stereo mix to a binaural mix, you have a difference of level. And just this difference of level, as we know, is enough to change the perception, making the stereo version more exciting. So with Apple, what they’re doing is for spatial audio, they are readjusting by reinforcing the bass and adding a bit of reverb. So when you move to spatial audio from a stereo file, you say, ‘Wow, it’s quite good.’ But it’s not binaural.

“What we’ve done with Oxymore is actually to develop some mastering tools in‑house to optimise the level and also to try to adjust what, in my opinion, is missing in lots of binaural mixes: the lack of bass and lack of dynamics in the low mid. We really put a lot of attention on that because at the moment it’s difficult, with the same file, to have an ideal low‑mid and bass for speakers, and with the same file, width for headphones. You have to choose. And then I took the option to do separate files for headphones and speakers.

“Having said that, I’ve been quite impressed recently by the fact that with Dolby Atmos on Apple, if you have good mastering, like we tried to do, the same file is quite OK in binaural and 5.1. You lose a little bit of space. So we still have a work in progress, but I really try to improve with the tools we have today for this project. And hopefully, I think this project and the energy we put in this project will help also, or contribute to help some developers and some brands such as Dolby to also help the musicians and the music community. We are still in the dark age of multi‑channel, binaural and immersive sounds, which is quite exciting in a sense, because we can work with companies to progress together and to define a proper grammar for music and not only for movies.”

The Cristal Baschet

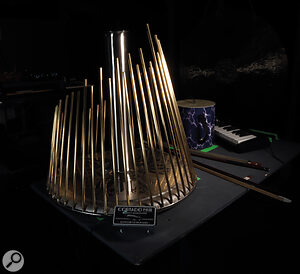

The Cristal Baschet: part instrument, part sculpture.“I sampled a lot of this instrument for Oxymore,” says Jean‑Michel Jarre of the extraordinary Cristal Baschet, an instrument created by brothers Bernard and François Baschet in the early ’50s. “They were calling their instruments structures sonore. That means sound or sonic structures. They were quite influenced by [Alexander] Calder, the sculptor, and their instruments were absolutely stunning in terms of aesthetics. They were sculptures in themselves.”

The Cristal Baschet: part instrument, part sculpture.“I sampled a lot of this instrument for Oxymore,” says Jean‑Michel Jarre of the extraordinary Cristal Baschet, an instrument created by brothers Bernard and François Baschet in the early ’50s. “They were calling their instruments structures sonore. That means sound or sonic structures. They were quite influenced by [Alexander] Calder, the sculptor, and their instruments were absolutely stunning in terms of aesthetics. They were sculptures in themselves.”

The instrument is related to the glass harmonica, and is played by rubbing rods of different lengths with wet fingers. The resulting vibrations are amplified by shaped metal resonators. “It creates a very, very strong sound, almost like low trombones, and it can be very, very brutal, very violent, as well as very subtle. They developed also lots of percussion instruments with springs and also lots of metallic parts. But always, the aesthetic was very important. They had this idea that beauty and the shape of an instrument is very important in the musical result. And actually, it’s true.

“The shape of a violin, the shape of a guitar: you develop almost a sensual relationship with an instrument, which is of course desperately lacking in the electronic gear where you still have this box. Very few people have been focused on the real aesthetic of electronic instruments. This is lacking. And the Baschet brothers were really obsessed by that. It’s really like a sculpture. And you can scream or sing into it and it creates a... I don’t know, dinosaur‑like voice. It’s quite interesting. It’s a physical synthesizer, because you can really create sounds and make them evolve, like if you are moving some oscillators. It’s exactly the same thing.”