To help you brush up on your listening skills, we examine the production of some recent hits.

Lewis Capaldi

I was immediately struck by the similarities between this song and James Arthur’s ‘Say You Won’t Let Go’ (see SOS January 2017’s column). Both plough the same trusty old I-V-vi-IV furrow familiar from hits such as Bob Marley’s ‘No Woman No Cry’, U2’s ‘With Or Without You’, and Jason Mraz’s ‘I’m Yours’. Both artists sing as if doing their British best to avoid anyone glimpsing their teeth. Both voices boast an impressively ragged upper-register wail, yet aren’t shy about sprinkling in falsetto moments to underline the earnestness of their repressed emotions. Yes, Capaldi seems able to push his chest voice a little higher, and ekes out a bit more rock-style edge at his louder moments, but I honestly can’t help feeling a bit underwhelmed. Was the world really missing this?

Besides the symptoms of acute musical jaundice, however, there are a couple of other small elements of the vocal production that bug me a little. The first is the song’s middle section. Pleased as I was for its brief respite from I-V-vi-IV, the implausibility of his unbroken 15-second vocal line (sung at full force at the very top of his register, without a single breath) insidiously undermined the authenticity of his delivery for me. Now, I’m sure there’ll be some fans arguing he actually sang it that way, but I don’t really buy it given the half-dozen live performances I’ve seen, which all feature mid-phrase breathing despite their being transposed at least a tone downwards from the key of the original chart release. Clearly, studio production always involves some artifice, but the moment the listener begins to doubt whether they’re hearing a plausibly natural vocal, it calls into question the singer’s emotional credibility as a whole. And what’s left of an artist like Capaldi once you strip that away?

The other niggle is somewhat in the same vein: the way the song’s final word finishes so abruptly. However, I’m more in two minds about this. Again, it feels more like an edit than anything a singer would naturally do. But, unnatural as it is, there’s something quite appealing about it on an emotional level, almost as if our audio connection to the singer has been severed prematurely, or as if the whole song had been some kind of vivid flashback that we’ve just snapped back out of. Mike Senior

Brandi Carlile

With this kind of combination of voice and song, Brandi Carlile more than deserved her recent Grammy hat trick. Reminiscent of Thom Yorke in her combination of emotional fragility and defiant high-register howl, she also boasts a richly expressive vibrato on words like “spin” (1:11), “girl” (1:46), and “on” (3:35) — a mannerism that very few artists can pull off without sounding self-consciously ‘stagey’. Moreover, it’s wonderful to hear a modern vocal performance on which I can detect no signs of pitch correction, and which is unquestionably more powerfully affecting as a result. As such it should probably be required listening for every music tech course on the planet.

The harmonies reward scrutiny too, firstly because the main verse progression’s Am chord puts us in Mixolydian mode — a canny move for a bittersweet song, given that the minor dominant allows no easy perfect-cadence resolution (ie. V-I), so the more elegiac plagal cadence (IV-I) becomes the strongest game in town. Incidentally, if you’re looking for a quick route to more interesting harmonic progressions without resorting to fussy chords, modal techniques like this are a good bet in general. In this case, though, the chorus also expands on the minor dominant by adding a minor subdominant too, extending the verse’s I-v-IV-I to I‑v‑IV‑iv, such that the (now intensified) plagal cadence resolves across the boundary between four-bar sections, rather than within the four-bar unit, thereby increasing the musical momentum to my ears.

But as the progression starts going round for the second time, the Am is suddenly substituted with an exhilaratingly chromatic F# chord, hinting at modulation to the relative minor. The moment of euphoria is short-lived, however, as it’s thwarted by a kind of interrupted cadence to G in the following bar, returning us to the IV-iv-I cadence formula. What’s particularly cool about that F# chord, is that its third (A#) is enharmonically the same note as the Gm chord’s third (Bb) two bars later, but where the former’s voice-leading (as a chromatically raised note) pulls it up to B, the latter’s voice-leading (as a chromatically lowered note) impels it downwards to A. Maybe it’s just me, but I think there’s something about that multivalency that suits Carlile’s lyric perfectly. Mike Senior

Mark Ronson feat. Miley Cyrus

Poor old Miley — no matter what she does, I never seem to be able to find it in my heart to take her seriously. Where ‘Wrecking Ball’ (see April 2014’s column) came off like discount P!nk, this latest stylistic foray feels like she’s pitching for a slice of Lady Gaga’s recent singer-songwriter reinvention (in which Ronson had a hand). Convenient, then, that a trace of her native Tennessee twang suddenly appears to be emerging from behind the Malibu facade that has concealed it for so many years. Don’t blink, though, because I’m not sure how long it’ll last...

Anyway, I like the way this production plays with the lengths of the different song sections. So, for instance, the chorus develops from the beatless eight-bar fragment at 0:08 into the first full 16-bar statement at 0:55. Then, by expanding the final four-bar segment with various internal repetitions, we get the 22-bar choruses at 1:54 and 2:48, the latter continuing its four-to-the-floor pattern for four bars longer. The first pre‑chorus also increases its length from two bars at 0:50 to four bars at 1:45 and 2:40. All of this makes sense, in terms of maximising the impact of the chorus melody and the pre‑chorus’ “nothin’ goin’ save us now” riff. Likewise, the shortening of verse 2 to eight bars also stands to reason, as the lead vocal inevitably won’t hold the listener’s interest as well as it did in verse 1, and this truncation also means that the choruses progressively get closer to each other as the song progresses: there are 14 bars between the first two choruses; only 12 bars between choruses 2 and 3; and only four bars between choruses 3 and 4.

You often hear mix engineers using momentary delay ‘spins’ as ear candy, but you don’t often hear reverb employed in this way nowadays, so I was pleased to hear the sudden extra bloom on the repeated vocal phrases at the end of each four-bar verse segment (eg. “we both know it” at 0:31 and “it’s blowin’” at 1:34), as well as on the first pre‑chorus’ “us now” (0:52). What elevates this trick further, though, is that the same kind of reverb also swathes the hummed backing-vocal countermelody at the tail end of the chorus (first heard at 1:21), so the idea in general feels more ‘built in’ than ‘stuck on’, if you see what I mean. Oh, and before you go, don’t miss the lovely little reverse-guitar layer at 1:06. Mike Senior

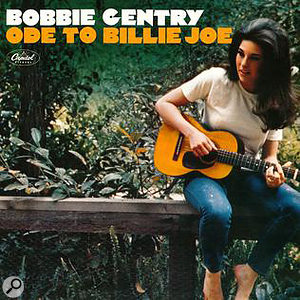

Classic Mix: Bobbie Gentry ‘Ode To Billie Joe’ (1967)

As a podcast creator arriving at the party just as the Zeitgeist seems to be fetching its coat, I’ve been bingeing my way through various celebrated music-related series, and can thank Tyler Mahan Coe’s Cocaine & Rhinestones for introducing me to this classic country single by Bobbie Gentry. It seems that the song’s main acoustic guitar and vocal parts were just a demo recording Gentry did for Capitol Records, but that the label loved the performance, so hired top arranger Jimmie Haskell to flesh it out with some strings. That chart netted him the first of his three Grammies (the others being for Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ and Chicago’s ‘If You Leave Me Now’), and with good reason.

As a podcast creator arriving at the party just as the Zeitgeist seems to be fetching its coat, I’ve been bingeing my way through various celebrated music-related series, and can thank Tyler Mahan Coe’s Cocaine & Rhinestones for introducing me to this classic country single by Bobbie Gentry. It seems that the song’s main acoustic guitar and vocal parts were just a demo recording Gentry did for Capitol Records, but that the label loved the performance, so hired top arranger Jimmie Haskell to flesh it out with some strings. That chart netted him the first of his three Grammies (the others being for Simon & Garfunkel’s ‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’ and Chicago’s ‘If You Leave Me Now’), and with good reason.

Most striking, for me, is his use of dissonant chromatic notes. Right from the outset, the first violin figure at 0:03 pits its woozy C# fall-off against the clearly audible C of the guitar’s bluesy D7 chord. The ‘bass’ part (actually a pizzicato cello within the string arrangement) repeatedly delivers clashing C# and F# eighth-note decorations against the guitar’s D9 and G7 chords respectively. Right at the end of verse 2, the violins set their languorous F-to-F# violin line against the F# of the guitar’s D chord, before directly clashing their C against the bass line’s C# eighth note at 1:03. Just as the novelty of these tactics begins to fade, the end of verse 4 treats us to two new chromatic notes: the cello line’s Bb at 3:18 and, even more startlingly, the violin’s high Ab at 3:56, the latter left hanging unresolved until the production’s weird chromatic coda fills in all the remaining semitones with its asynchronous falling violin and cello lines.

The string writing also serves to underscore many aspects of the lyric. At the simplest level, the dark significance of each verse’s “off the Tallahatchie Bridge” hook is enhanced not only by the cello switching from pizzicato to sustained bowing, but also by featuring the instrument’s lowest note (its open C string), an austerely resonant sonority that appears nowhere else in the song. The high violin line in verse 3 (which avoids the C-C# clash at 1:50 and 1:58) lightens the mood as the narrator’s brother reminisces about childhood pranks; the block harmony and parallel thirds at 2:05 clearly reflect the words “after church on Sunday night”; and the richer low-register violins at 2:31 give warmth to the mother’s concern about her daughter’s loss of appetite, while the optimistic rising B-C#-D line at 2:54 hints at her ulterior motives in inviting “that nice young preacher” to dinner. But my own personal highlight is that Haskell chooses to leave the strings tacet (bar the pizzicato bass) for the song’s celebrated “throwing something off the Tallahaskie Bridge” lyrical MacGuffin, a move that I can’t help comparing with that scene in Psycho where Bernard Hermann keeps schtum as Marion’s car and its grisly cargo sinks into the marsh! Mike Senior