Apple iPad Mini

Tablet Computer

As a company, Apple like to make 'mini' products. There were iPods, and then there were iPod Minis; there were Macs, and then there were Mac Minis. In both cases, these Mini products were created to broaden the appeal of the original to a wider set of users, with a reduction in both size and cost. So with Android-based tablets now attracting users with smaller form factors, it was perhaps inevitable that Apple would apply its Mini formula to the iPad. A studio in the palm of your hand. For music and audio apps, the iPad Mini offers roughly the same performances as the third-generation iPad, but in a lighter, more slender and cheaper package.

A studio in the palm of your hand. For music and audio apps, the iPad Mini offers roughly the same performances as the third-generation iPad, but in a lighter, more slender and cheaper package.

The first thing you can't fail to notice about the iPad Mini is how little it weighs: the regular 652g iPad seems like a brick after you've spent time with the 308g Mini! The second thing you'll notice is the iPad Mini's slender frame. With a depth of just 7.2mm, it's fractionally thinner than the 7.6mm-deep iPhone 5 and a good deal slimmer than the iPad, which has a depth of 9.4mm. While these improvements may seem trivial, I think I'm far more likely to keep an iPad Mini in my bag at all times than I was an iPad. If you use — or feel you would use — an iPad mostly as a studio peripheral, these Mini qualities may not be all that important, but if you want a handy device that's with you all the time, they're definitely a bonus.

Aesthetically, the iPad Mini looks like the result of a particularly amorous night between an iPad and an iPhone 5. The black model is now completely black, with an anodised aluminium enclosure, while the white alternative retains its metallic-looking rear. And, like the iPhone 5, the iPad Mini's design incorporates a diamond-cut chamfer that joins the aluminium back with the glass front, giving the device an elegant and seamless finish. The only aspect of the iPad Mini's design that feels initially awkward is the width (or lack thereof) of the left and right borders when the device is in portrait orientation. However, I'm not sure this matters if you're running music software, since the majority of audio-related apps seem hard-wired to use landscape mode anyway.

Apple have chosen a 7.9-inch display for the iPad Mini (compared to the iPad's 9.7-inch screen), offering the same 1024x768 resolution as the original iPad and the iPad 2. This means that the iPad Mini can run existing apps without modification, although everything appears slightly smaller, due to the higher pixel density. I was a little unsure as to how comfortable this would be, since the size of user interface controls always seemed perfect on the iPad, but in practice, I can't say I experienced any significant impairment. Apps like Garageband work just fine, and more complex apps, such as Wolfgang Palm's brilliant WaveGenerator, are usable in exactly the same way they are with a bigger display. While the toolbar buttons seem almost Lilliputian in Korg's MS20 app, I rarely made an erroneous tap. Even control surface apps like Neyrinck's V-Control seem practical with the Mini, although some users may prefer the luxury of the regular iPad's larger and clearer Retina display for such apps.

The iPad Mini features Apple's new Lightning connector. Happily, an adaptor for your 30-pin devices is available.Internally, the iPad Mini features the same A5 SoC (system-on-a-chip) as the iPad 2, offering two ARM cores running at 1GHz, two graphics cores, and 512MB memory. This means that you can expect the same level of performance with the iPad Mini as the iPad 2, but it also means that the iPad Mini offers roughly the same level of general processing performance (minus the extra memory and graphics cores) as the third-generation iPad. Indeed, using Geekbench, my third-generation iPad scored 749 while my iPad Mini won out slightly with a score of 750. (This is because the third-generation iPad's A5X chip features the same dual ARM cores as the A5.)

The iPad Mini features Apple's new Lightning connector. Happily, an adaptor for your 30-pin devices is available.Internally, the iPad Mini features the same A5 SoC (system-on-a-chip) as the iPad 2, offering two ARM cores running at 1GHz, two graphics cores, and 512MB memory. This means that you can expect the same level of performance with the iPad Mini as the iPad 2, but it also means that the iPad Mini offers roughly the same level of general processing performance (minus the extra memory and graphics cores) as the third-generation iPad. Indeed, using Geekbench, my third-generation iPad scored 749 while my iPad Mini won out slightly with a score of 750. (This is because the third-generation iPad's A5X chip features the same dual ARM cores as the A5.)

Like the recently introduced iPhone 5, the iPad Mini employs Apple's new Lightning connector, replacing the trusty old 30-pin iPod connector. For musicians (particularly those with legacy iOS hardware and peripherals), the change in connector is potentially something of a pain, although Apple do offer Lightning to 30-pin adaptors (starting at £25$29) that should be compatible with most third-party accessories. Apple have also made available a new Lightning USB Camera Adaptor for £25$29, which enabled me to connect my class-compliant USB MIDI keyboard to the iPad Mini without any problems. The only annoyance I have with this particular accessory is that it isn't supported by the iPhone 5, which seems really stupid.

In its lifetime, the iPod Mini eventually became Apple's most popular iPod, and it's not hard to imagine history repeating itself with the iPad Mini. It offers the same level of performance as the second- and (for the most part) third-generation iPads, but in a desirably thin and light form factor and at a lower cost. The iPad Mini might not be as cheap as other smaller tablets (Google's 16GB Nexus 7, for example, retails at £199$199), but it's cheap relative to the cost of an iPad, and iOS has, without a doubt, the best selection of music and audio apps. If you want the extra performance and additional memory offered by the A6X chip (see box), a fourth-generation iPad is the only way to go. Otherwise, if you're happy with the idea of a smaller and cheaper iPad 2, the iPad Mini is a very attractive option. Mark Wherry

Prices from £269.

Prices from $329.

What Apple's A6 Chips Mean For Mobile Musicians

In addition to launching the iPad Mini, Apple have also released a 4th-generation iPad less than eight months after the previous model — which the company had been calling simply "the new iPad” — went on sale. This new, new iPad is almost identical to the old, new iPad except for two important distinctions: firstly, it uses Apple's new Lightning connector (discussed in the iPad Mini review); and secondly, the device is powered by Apple's new A6X SoC (system-on-a-chip).

The A6X is Apple's third iteration of their A-series custom silicon this year and builds on the significant performance improvements first seen in the A6 used in the iPhone 5. As usual, Apple have remained quiet on the viscera of its chips; however, also as usual, many people have been uncovering their secrets and reporting on various online publications. According to these sources, the A6 features an Apple-customised, dual-core ARM processor running at 1.3GHz, along with three GPU cores and 1GB memory. The A6X offers the same dual-core ARM processor, but clocked faster at 1.4GHz, and features quad-core graphics. With all of these improvements, Apple claim that the fourth-generation iPad offers twice the CPU performance and twice the GPU performance of its predecessor.

It's possible to confirm some of these details by using benchmarking software such as Geekbench, and this can also provide some insight into the relative theoretical performance of Apple's iOS-based devices. Looking at the numbers provided by Geekbench Browser, an iPhone 5 with an A6 chip scores an impressive 1568 (the A5-powered iPhone 4S scores just 655), and the Wi-Fi fourth-generation iPad is even better with a score of 1754 (the Browser score for the Wi-Fi third-generation iPad is 790).

What's particularly interesting about the Geekbench scores is that the baseline score of 1000 represents the score of a single-processor 1.6GHz PowerMac G5, meaning that both the iPhone 5 and latest iPad clearly offer more performance than a nine-year-old PowerMac. In fact, the new iPad offers roughly the same performance as a 2004 PowerMac G5 with dual 2GHz processors. And while this might seem a little nostalgic, I think it's an indication of just how powerful these mobile devices are becoming, especially since people were able to produce fairly complex music and audio work with such a machine.

One caveat I should mention, though, before one gets too excited about these numbers, is that not every app is going to perform twice as well just because it's running on Apple's latest hardware — at least, not straight away. In order to take full advantage of Apple's engineering in the A6 and A6X's ARM cores, an app will need to be recompiled with support for the new architecture in the latest version of Xcode. Existing apps run fine on the A6 and A6X, of course, but you won't experience a significant improvement until developers start releasing new versions of their wares. Mark Wherry

Microsoft Surface

Tablet Computer

Microsoft have been noticeably absent in the recent rise of tablet computing. Despite being one of the first companies involved in this area (going all the way back to Windows for Pen Computing in 1991), it wasn't until last year that they unveiled Windows 8 to compete in the post-iPad world. However, there must have been a feeling that a software-only strategy wasn't going to be enough this time around, so earlier in the year Microsoft unveiled their own Surface tablet devices — the first time the company have ever made personal computer hardware in their 37-year history.

Is it a tablet, or is it a laptop? The Surface's Kickstand and Touch Cover represent design decisions that differentiate Microsoft's offering from the competition.Released on the same day as Windows 8, the Surface looks pleasingly sophisticated to the eye, with an effortlessly modern design that appears less cuddly than an iPad. The device is forged by injection moulding magnesium in a process that Microsoft call VaporMg, and the result is unquestionably sturdy, though perhaps not quite as comfortable to hold as an iPad. Whereas the third-generation Wi-Fi+Cellular iPad (at 1.46 pounds) feels a little heavy when you first pick it up in a way you soon forget, the Wi-Fi-only Surface (at only 1.5 pounds) somehow feels kind of heavy when you pick it up and continues to feel that way as you use it. I was also going to write that the Surface was slightly bulkier, but, surprisingly, it turned out that both devices are 0.37 inches thick.

Is it a tablet, or is it a laptop? The Surface's Kickstand and Touch Cover represent design decisions that differentiate Microsoft's offering from the competition.Released on the same day as Windows 8, the Surface looks pleasingly sophisticated to the eye, with an effortlessly modern design that appears less cuddly than an iPad. The device is forged by injection moulding magnesium in a process that Microsoft call VaporMg, and the result is unquestionably sturdy, though perhaps not quite as comfortable to hold as an iPad. Whereas the third-generation Wi-Fi+Cellular iPad (at 1.46 pounds) feels a little heavy when you first pick it up in a way you soon forget, the Wi-Fi-only Surface (at only 1.5 pounds) somehow feels kind of heavy when you pick it up and continues to feel that way as you use it. I was also going to write that the Surface was slightly bulkier, but, surprisingly, it turned out that both devices are 0.37 inches thick.

One of the most significant ways in which the Surface's design differs from the iPad is that Microsoft have included a screen with a 1366 x 768 resolution, and thus a 16:9 aspect ratio. This makes the device almost comically tall if you hold it in portrait mode, though this clearly isn't the orientation in which the Surface is intended to be used, which might actually be a good thing for music and audio apps. As I mentioned in the iPad Mini review, most iOS apps in this field are designed for landscape use, and this makes a great deal of sense. Music and audio surfaces generally make good use of horizontal space: mixers show channels horizontally in the same way piano keyboards show pitches. So having a 16:9 display could be very useful.

A particularly nice touch in the Surface's design is the incorporation of the so-called Kickstand. Rather than needing third-party assistance to prop itself up, the Surface incorporates a neat stand that flips out behind the device. It's actually quite a nice idea, and the only minor complaint is that it would be better if it could have been adjustable, a bit like the old Apple Cinema Displays, as sometimes the angle at which the Surface stands is just a little steeper than you might like.

Internally, the Surface is powered by Nvidia's Tegra 3 SoC (System-on-a-Chip), featuring a quad-core ARM processor, GeForce graphics and 2GB memory, running a variant of Windows 8 designed for this architecture and called Windows RT. Although Windows RT is able to run the new tablet-style apps you can download from the Windows store, just like Windows 8, and even has access to the Windows Desktop, it cannot run third-party applications on the desktop, only the built-in versions of Word, Excel, and PowerPoint. If you would like a Surface that could run Cubase, or Sonar, or Live or any other desktop application, however, all is not lost. Microsoft have also announced the upcoming Surface Pro, featuring an Intel Atom processor that runs the full version of Windows 8 Pro.

As good as it gets: Revel Software's Piano Time is one of the few music-related apps currently available for Windows RT.The fact there will be Surfaces (and other Windows tablets made by third parties) running both ARM and more conventional PC architectures highlights the main point of Microsoft's strategy. Rather than scaling up from the phone, as Apple and Google have done, Microsoft's vision is that apps written to take advantage of the new touch user interface will be able to run on both tablets and regular Windows-based computers. From Microsoft's perspective, the tablet is just another PC form factor.

As good as it gets: Revel Software's Piano Time is one of the few music-related apps currently available for Windows RT.The fact there will be Surfaces (and other Windows tablets made by third parties) running both ARM and more conventional PC architectures highlights the main point of Microsoft's strategy. Rather than scaling up from the phone, as Apple and Google have done, Microsoft's vision is that apps written to take advantage of the new touch user interface will be able to run on both tablets and regular Windows-based computers. From Microsoft's perspective, the tablet is just another PC form factor.

This could be very exciting for music and audio apps, as was indicated in a demo given by keyboard player Jordan Rudess at Microsoft's recent BUILD conference. There, he demonstrated beta Windows versions of his company's MorphWiz and Tachyon apps on both a Surface and a Lenovo all-in-one desktop PC with a 27-inch, multi-touch display. While Apple think touch is just for phones and tablets — and have been vocally hesitant to build it into MacBooks or iMacs — Microsoft clearly see touch-based interfaces scaling in both directions.

All of this is great, of course, but a tablet is ultimately only as useful as the apps that are actually available, and this is where the Surface faces its biggest challenge. You can probably already guess that, right now at least, there aren't many music and audio-related apps you can run on the Surface. The Music category of the Windows Store is lacking in both quality and quantity, with the majority of apps geared towards listening to music rather than creating it. At the time of writing, there were a few pathetic piano apps, a number of guitar-oriented apps, and an ear trainer.

One possible reason for this limited selection is that RT doesn't support MIDI. So even though Surface has a regular USB port built-in, you won't be able to connect and use a MIDI class compliant device in the same way you might with an iPad (and the necessary adaptor). However, it must also be said that iOS didn't support MIDI directly until version 4.2, and this didn't stop developers from writing music software for the iPhone or iPad and implementing network-based workarounds or, in some cases, their own dedicated hardware.

The situation for audio support is potentially a little better, since RT uses WASAPI (Windows Audio Session API) for low-latency audio via the built-in audio hardware and headphone jack. While you can't connect a Windows-compatible USB audio interface to the Surface right now, that the device implements a standard Windows audio API might offer a glimmer of hope that this could be possible in the future if developers can create their own suitable drivers.

Surface is available in 32 or 64GB models, although the device reserves 16GB for the system. This is a little surprising, since it's unlikely Microsoft need all that space, but by way of compensation, the 32GB model does at least cost the same as a 16GB iPad. Microsoft also offer a Touch Cover and a Type Cover, both of which neatly incorporate a keyboard into their design and are necessary to make full use of Windows RT's Desktop mode (though you could attach any USB keyboard and mouse). I didn't try the Touch Cover, but the more expensive Type Cover was surprisingly usable.

I really want to like the Surface. It's clear some brilliant thinking has gone into this product, and Microsoft have been justly praised for taking a fresh approach in both its hardware and software design. But a great deal of polish is still required to make the device feel as slick as some of the competition, and while such teething troubles could be overlooked if there were some killer apps available, this is, sadly, not the case. Microsoft's Surface has the potential to one day become a serious contender for tablet-savvy musicians and audio engineers, but not today. Mark Wherry

Prices from £399.

Prices from $499.

Borderlands

Granular Synth App For iPad

Borderlands is a granular synthesis application developed by Chris Carlson, as a follow-on from research conducted for a Master's thesis at CCRMA in Stanford. Granular synthesis is a well-established sound generation technique: source material is dynamically sampled into short 'grains' which can be played back en masse and individually looped, layered and shifted in pitch, generating anything from soft ambient washes to wild, glitchy walls of sound. Granular synthesis fans (myself included) like it for the degree of real-time control that's possible, making it a good method for sonic exploration and improvisation.

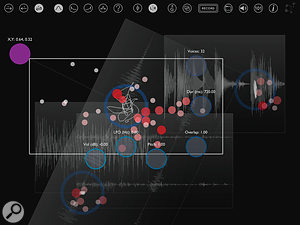

Borderlands: If this was the view on the radar screen on the bridge of your submarine, you'd be in real trouble.Borderlands takes classic granular synthesis and clothes it in a beautiful and enticing visual interface for the iPad. The conceptual model is of 'clouds' — the sound-generation components — floating over a 'landscape' of audio material. The landscape is assembled from audio files whose waveform displays are laid out in whatever arrangement you want: they can be dragged around, superimposed, and even scaled and rotated with two-finger gestures. Borderlands ships with a selection of demo audio files, but will also load files from an iTunes playlist named 'Borderlands' if one exists.

Borderlands: If this was the view on the radar screen on the bridge of your submarine, you'd be in real trouble.Borderlands takes classic granular synthesis and clothes it in a beautiful and enticing visual interface for the iPad. The conceptual model is of 'clouds' — the sound-generation components — floating over a 'landscape' of audio material. The landscape is assembled from audio files whose waveform displays are laid out in whatever arrangement you want: they can be dragged around, superimposed, and even scaled and rotated with two-finger gestures. Borderlands ships with a selection of demo audio files, but will also load files from an iTunes playlist named 'Borderlands' if one exists.

Double-tap anywhere in the landscape to create a cloud, which is a single granular synthesis generator with its own set of programming parameters. You can have as many distinct clouds as you like, and drag them anywhere in the landscape; or, for that matter, drag waveform displays around under the clouds. Double-tap a cloud to reveal a cluster of pads which behave as parameter sliders for volume, pitch, grain overlap, duration, LFO and voice count. A menu bar allows changes to playback direction, grain envelope and stereo placement (in-place versus alternate left-right).

Every cloud has a variable X-Y rectangle which determines its sampling range over the underlying audio. Red dots appear in the rectangle as grains are triggered, sample position and amplitude varying according to each grain's position on the waveform data below it. A single cloud might sit over multiple waveforms, aligned at different angles, for complex layering of source material.

Physics modelling means that waveforms and clouds have mass and momentum, making interaction smooth, easy and fun. A gravity mode lets you tilt the iPad to move the clouds around like hockey pucks. Be careful, because if a cloud falls off the edge of the screen, it's destroyed! A record mode captures the output of Borderlands, and recordings can be uploaded to SoundCloud.

Borderlands is a lovely piece of design and a joy to use for exploring existing audio and generating new material. It is rather CPU-intensive: while it's happy on my Retina iPad, an iPad 1 would struggle to keep up. It also has some flaws: there's no screen rotation support, file import (iTunes) and export (SoundCloud) are inconvenient (audio copy/paste and/or DropBox support would be better for studio workflow), and the app doesn't run in the background or disable an iPad's auto-off setting. Those (fixable) issues aside, Borderlands is beautiful, creative and addictive: well worth the price of a latte. Nick Rothwell