Offering all the essential facilities at a lower price point, could the new Core version of the Tube Amp Expander be a serious competitor to the original flagship model?

The Boss division of Roland announced their original flagship Waza Tube Amp Expander at 2019’s Winter NAMM show, putting it head‑to‑head with Universal Audio’s OX tube‑amp load box and speaker simulator, and we reviewed it in SOS September 2019. Five years on, that ‘big box’ version is now joined by the TAE Core, which is half the size and half the price, but offers by no means half the functionality. The TAE Core, like the original TAE, facilitates direct recording of a tube amp without the need for a guitar speaker. The amp feeds the TAE’s dummy load, where a line‑level signal is derived to pass through an A‑D converter. A range of digital effects can then be activated, before the signal is split into two paths: one to feed an impulse‑response host, where you can access both the integral cabs and any other speaker IRs you may choose to load; and the other to feed an internal solid‑state power amp to use with a real speaker.

Overview

The Core’s reactive load is switchable between 4, 8 and 16 Ω, with power‑matching options of 10, 50 and 100 Watts, primarily I’d imagine for internal level optimisation. Maximum power input is stated as 100W, and there is a ‘safety load’ in place if you forget to power up the TAE before switching the amp on. Once you are all hooked up, the Speaker Out socket on the back of the TAE Core, which is fed from the internal 30W power amp, can then be used to hear your safely‑loaded amp at whatever volume setting you like, via a fully variable (not stepped) level control on the front. A pair of balanced XLRs convey the DI path’s speaker‑emulated signal to a PA mixer or recording system.

Apart from the fact that it was possibly the first integrated re‑amping solution, as opposed to an attenuator, the original TAE’s ‘big thing’ was that it offered a user‑adjustable impedance curve, rather than the fixed response offered by most dummy load/attenuator boxes. It offered 16 possible response shapes via its Resonance Z and Presence Z front‑panel switches. In the guitar world, we tend to think of speakers just in terms of 4, 8 or 16 Ω units, but an actual impedance will always vary significantly across the whole frequency range. The significance of this parameter is that the impedance curve determines the power transfer at different frequencies, which, of course, becomes a factor in the actual sound that we hear. The purpose of including the user‑adjustable reactive load is that it allows the user to approximate the impedance curve of a number of different types of speaker, thereby making the connected amp behave more accurately like it would if it were connected to that specific driver.

With a block diagram printed on the top of the TAE Core, you’ll never be in any doubt about the signal flow.

With a block diagram printed on the top of the TAE Core, you’ll never be in any doubt about the signal flow.

Now, the reason I’m dwelling on these controls on the original model within a review of the new one is that the TAE Core doesn’t have them... But I think it is none the worse for it. The load settings for the Core are just a choice of Combo or Stack, perhaps replicating a single‑driver open‑back cab and a closed‑back 4x12. Whilst the more sophisticated control setup could allow you to fine‑tune an exact the response, it could also allow you to get it a bit wrong. A single, fixed impedance curve is likely to be optimised for just one type or the other, but a choice of the two primary types really has got you covered without having to think too deeply about it. Yes, the impedance curve matters, but so do all the other variables — the virtual mics, the effects and EQ, and the room ambience — as well.

Speaker Emulation

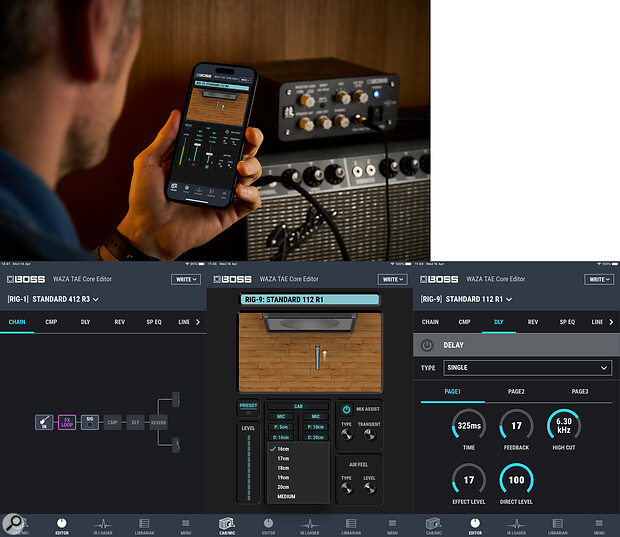

Air Feel is a clever effect that can counter the dryness of close‑miked IRs, leaving you a sound that can make playing feel more comfortable.You can use the TAE Core’s speaker‑emulated outputs straight out of the box without firing up the dedicated software editor — there’s a speaker and effects setup stored in every one of the 10 settings of the front‑panel Rig control — but you’d be missing out on quite a lot. The editor, available now in both desktop and mobile formats, and connecting over USB‑C or (using an optional adaptor) Bluetooth, allows you to store your own Rigs (whole setups of routing, IR, EQ and effects), with 10 of these able to reside within the TAE hardware for instant recall via the front‑panel control, the app, or MIDI, whilst many more can be stored in your library via the app. The editor improves on the original TAE editor in that it now also includes the IR loader, which makes a lot more sense than having separate apps.

Air Feel is a clever effect that can counter the dryness of close‑miked IRs, leaving you a sound that can make playing feel more comfortable.You can use the TAE Core’s speaker‑emulated outputs straight out of the box without firing up the dedicated software editor — there’s a speaker and effects setup stored in every one of the 10 settings of the front‑panel Rig control — but you’d be missing out on quite a lot. The editor, available now in both desktop and mobile formats, and connecting over USB‑C or (using an optional adaptor) Bluetooth, allows you to store your own Rigs (whole setups of routing, IR, EQ and effects), with 10 of these able to reside within the TAE hardware for instant recall via the front‑panel control, the app, or MIDI, whilst many more can be stored in your library via the app. The editor improves on the original TAE editor in that it now also includes the IR loader, which makes a lot more sense than having separate apps.

Apart from the Speaker Out level and reactive load setting, the only other control knobs on the front are the 10‑way Rig selector, line out, phones level and ‘Air Feel Level’. This last control is a tight, stereo ambience applied to the line out, headphones and USB digital outputs, but, logically, not the speaker feed. Air Feel opens out the close‑miked dryness of the IRs into something more like an in‑the‑room sound that is far more comfortable to play with, without having to make the sound noticeably reverberant unless you turn it up a long way.

Rear Panel Connectivity

Round the back, power connection is from a 12V DC external adaptor, with a chunky right‑angle connector that inspires a lot more confidence than the standard DC connector used for pedals. There’s now a single speaker output; the ‘big’ TAE had a paralleled pair. The power amp specs at 30W into 8Ω, with a minimum impedance of 4Ω (which would obviously give you a bit more output given that this is a solid‑state power stage). Driving a single 12‑inch speaker in an open‑back combo cab, I could comfortably get up to what counts as ‘performance volume’ for me these days. I guess it might not be enough in a large band line‑up with a hard‑hitting drummer, but who still gets to really crank it up on stage these days without being told to ‘turn it down’ and ‘get some in‑ears’? At lower levels, it’s great for just practicing with an authentic overdriven amp sound and, of course, it’s perfectly valid to still mic the speaker for recording rather than using an IR. It’s not exactly the same as having the output stage drive the speaker directly because you’ve broken the interactive feedback loop that gives that relationship some of its feel, but the moment you stop thinking about it and listen to what you’ve actually got, it’s perfectly fine!

The analogue line outputs appear as a stereo pair of XLRs. You can’t pan the mics, though, so the only stereo elements are the delays, the reverb and Air Feel effects, and the output from any stereo IRs you may have loaded. If there’s nothing important going on in the stereo field, you can of course just use one output for mono. An analogue send and return loop, switchable for ‑10dBV or +4dBu operation, allows you to patch in a hardware effects device, with the loop status (on/off, series/parallel) set as part of the stored data of a Rig.

For silent practice, the headphone output has independent level control, but there’s no obvious way of connecting a backing‑track player in the analogue domain, other than using an external mixer, as the effects loop input returns before the speaker‑sim stage, and you’d want the backing track to remain full‑range. The USB connection will let you do it, however, and you can also stream into it via Bluetooth. The TAE offers two USB audio output streams: Line and Pre‑Effect, the latter taking a mono signal from immediately after the external effects loop and thus before the internal effects and speaker sim. You can record from both simultaneously, so if you like the performance but not the sound, you can route the Pre‑Effect signal back through the TAE and try a different IR.

The rear panel has impressive connectivity options, including send and return jacks for an effects loop.

The rear panel has impressive connectivity options, including send and return jacks for an effects loop.

The revised version of the TAE editor is an improvement on the one for the original TAE, which was functional at best. In the Cab/Mic screen we’ve now got a simple pictorial representation of mic positions that change as you alter the distance and offset‑from‑centre parameters. It does help, especially when you are ‘positioning’ two mics. You can also change the cab type at this point, with a comprehensive choice of 4x12s, 4x10s, 2x12s, 1x12s, 1x10s and even three 1x8s.

As in the original TAE, some virtual cabinet setups are tagged as ‘for FOH’. These are usefully pre‑tweaked specifically for feeding a PA system, perhaps taking the mic slightly off‑centre to reduce harshness and taming a bit of the low end. I like what it does to the 4x12s even for recording, whilst some of the smaller speakers tend to lose a bit of the detail and idiosyncrasies that make them interesting, which is, of course, the point for FOH, where that stuff would just be lost anyway.

An interesting addition to the processing line‑up, along similar lines to the ‘FOH’ tweakery, is the new Mix Assist feature. This applies user‑variable degrees of EQ and dynamics processing, aiming to curate the final output, like a good engineer might, without you having to do it for yourself. Setting 1 “reduces the high‑frequency range that overlaps with the hi‑hat and the low‑frequency range that is difficult to distinguish from the kick or bass guitar, resulting in a sound that blends better when mixing” (basically a ‘bracketing’ EQ), while settings 2 and 3 combine this with varying degrees of mid push. The EQ works in conjunction with the Transient control, which you can use to target high‑level spikes or give the sound more attack. None of it is too extreme, so it is actually quite useful, and used to good effect in a number of the presets.

The mic choices of the original TAE (Shure SM57, Sennheiser MD 421, Neumann U87 and the slightly oddball AKG C451 — was that ever anyone’s first choice for miking a guitar cab?) remain, but are joined now by a Royer R‑121 ribbon. Yay! That’s great for pairing with one of the dynamic models. Flipping from Preset to IR mode lets you access the included set of very nicely curated Celestion IRs, or anything of your own you may have loaded. You can even tweak the time alignment of any double‑miked IRs, but not the distance and position, which is baked into the IR. User IRs need to be WAVs at 44.1, 48 or 96 kHz, 16‑/24‑bit linear or 32‑bit floating point. You can use mono or stereo IRs of up to 500ms — personally, I’ve never been able to discern any benefit in going that long, but I know others think differently so having the option makes sense.

The TAE Core can be configured using a desktop or phone app. Shown here are some of the screens from the mobile version.

The TAE Core can be configured using a desktop or phone app. Shown here are some of the screens from the mobile version.

Editor

The Editor page is a simple block diagram, with the ability to set parameters for the onboard compressor (modelling a dbx 160 or UREI 1178), delay (mono, stereo, faux‑analog, and Roland SDE‑3000), reverb (Halls, Rooms, Plate and Spring), plus separate EQ (parametric or graphic) for the speaker and line outputs, as well as speaker and line output level controls. The EQ can be employed as a useful Solo Boost facility, but there is also a global EQ that lives outside the Rig settings which you can use for ‘environmental compensation’, adapting the sound to the acoustics of your venue, perhaps. Like the line and speaker EQs, the global EQ can be both set and switched separately for each output, or tied together.

The effects appear in both the line and speaker outputs, as will anything patched into the effects loop, which gives you the option of ditching a pedalboard if you only have fairly basic effects requirements. You will have to use MIDI to control everything though, as there’s no option for using one of the nice Boss multi‑footswitch units that connect with just a TRS cable. You can get at all the parameters via MIDI CC messages, but if that’s a bit daunting you can save different effect statuses using the 10 onboard Rig slots (a TAE Core Rig is a single stored configuration of your cab and mic choices and effects settings) that you can then recall using simple MIDI Program Change messages. Sets of Rigs can be saved as LiveSets, perhaps for grouping Rigs together for a specific set list or a recording session.

The Last Word

The new Core edition of the TAE represents a well‑thought‑out rationalisation of the facilities of the ‘big’ TAE. It lacks nothing that I’d call essential, and ‘tidies up’ in a few places, as well. It’s significantly more affordable, easier to transport (the big one weighs a ton) and has a better app. One perceived limitation in this configuration, for some at least, is going to be the 30W power amp. On its own, it’s not quite enough to serve as ‘backline for the room’ with a loud band, but I guess the thinking is if you’re using a re‑amping attenuator to control volume, you probably don’t want to get it back up to the volume you started with. I think having just a bit more output would have been nice for the scenario where you are using the TAE Core to boost a little amp like a Champ up to stage levels, or indeed using a modeller into the effects return as an emergency backup rig.

You can switch in a compensating Fletcher‑Munson correction to boost low and high frequencies for when the re‑amping volume is set very low.

For recording, it’s fine. It might seem perverse to mic a re‑amped speaker when you’ve already got a line‑level IR recording output available, but it is sometimes just more comfortable for the player to be able to interact with a speaker in the room. Record both and see which one you like best. There’s a polarity flip on the speaker output to get it ‘round the right way’ with the IR if you need to, and you can switch in a compensating Fletcher‑Munson correction to boost low and high frequencies for when the re‑amping volume is set very low. Both the line and speaker paths go through the 32‑bit/96kHz converters — there’s no all‑analogue path through to the speaker — so there’s no digital latency offset between the two paths to worry about there.

Unless you’ve messed up your gain staging somewhere, the fundamental sound of the TAE Core is as sweet, clean and low‑noise as you could wish for. There is a fan, but while I hate to have anything with a fan in a control room, other than a little ‘check turn‑on’ when you first fire it up, I didn’t manage to get it to spring into cooling action. Running at full‑whack for a few minutes, I got too hot before it did! I’m sure it would have done if I’d fed a more powerful signal into it requiring more load dissipation.

Whilst the app is certainly better than the original TAE editor, personally I still find it disappointing that there’s no gain‑reduction metering for the compressors, and no visual interface for the EQs — that’s pretty standard stuff in any digital audio software these days. And the control scaling is still oddly dysfunctional in my opinion. You’ve got up to 2000ms of delay available, but the range from 0 to 400 or so — that’s the bit that most players are likely to actually use — is crammed into the bottom quarter of the rotation. Similarly, the halfway point on the reverb decay time is five seconds. Anyone used more than that on a guitar recently?

Finished whinging? Not quite. Having a desktop editor with a wired connection is great, but why does it have to require a ‘direct’ connection to the computer to work at all? My ports are all full of essential things, including hubs that are supposed to be for connecting ‘other things’... And the app takes an age to connect via Bluetooth — long enough to have you seriously wondering if it has stopped trying, and definitely something that would get you agitated if you needed an urgent remedial adjustment during a soundcheck. But, credit where it is due, it has never once actually failed to connect for me.

So, is there any reason to still buy the ‘full‑fat’ Tube Amp Expander? Well, a lot more power is the obvious one, and the ability to fine‑tune the load impedance curve, but there are also little useful facilities like the Amp Control feature for channel switching that can be set as a parameter within saved rigs, and the option to use a dedicated Boss footswitch. So there are plenty of reasons for both models to coexist. But if none of those things are a ‘must have’ for you, the new TAE Core is an absolute winner.

Pros

- Simplified reactance setting.

- IR loader now integrated into the editor.

- Improved software editor with connection via Bluetooth and USB‑C.

- Comprehensive remote control via MIDI.

- Fully variable ‘attenuated’ volume.

Cons

- Poor scaling of software controls.

- No gain‑reduction metering or EQ‑curve graphic in software editor.

- MIDI footswitching required for stage use.

Summary

The Boss Tube Amp Expander Core is a great little package — dummy load, speaker sim/IR host, integral power amp, onboard effects and MIDI control, at a significantly lower price point than the original. Whilst the control app is undoubtedly better than the original TAE editor, this version still feels a bit more like a ‘point‑one’ tweak than a ‘five‑years‑later’ revamp.

Information

£605 including VAT.

$699.

When you purchase via links on our site, SOS may earn an affiliate commission. More info...

When you purchase via links on our site, SOS may earn an affiliate commission. More info...