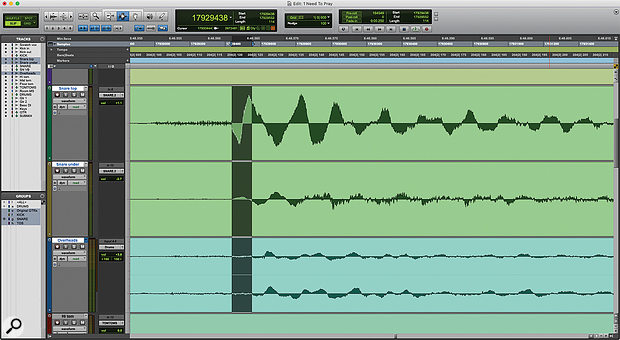

Measuring the delay between snare hits in the Snare Top track and in the Overheads track. Pro Tools reports the Length of the selection as 114 samples (centre, top).

Measuring the delay between snare hits in the Snare Top track and in the Overheads track. Pro Tools reports the Length of the selection as 114 samples (centre, top).

Time-alignment can help solve problems in multi-mic recordings — but it can also introduce new problems!

From pitch-correction to noise reduction, our software DAWs offer endless scope for 'improving' recorded sound. All too often, though, these tools are used in ways that fully justify the use of inverted commas around the word 'improving' — and that's certainly the case with the subject of this article!

We often use close and distant mics on the same source, especially when tracking drums. There are also many occasions on which a mic on one source picks up spill from something else that's being miked separately. In these situations, the same sound reaches the different microphones at different times. Sound travels at about one foot per millisecond so, for example, an overhead mic that's six feet above the snare will 'hear' each hit about 6ms later than the snare's close mic. Set the horizontal zoom level in your DAW high enough, and you'll see that each snare hit on the overhead tracks is a little to the right compared with the close-mic track. Good engineers learn to place mics so that the close and distant mics work well together despite these microscopic time differences, and will invert the polarity on some inputs, where appropriate.

Today, we have another option: we can 'fix' such timing differences in post-production. This is done at the mix rather than during recording, and the process is often called time-alignment. Like any 'fix it in the mix' tool, though, time-alignment is not a universal panacea. Neither is it a substitute for getting things right at the recording stage. It is always a compromise, and an alignment that improves the sound of one source can have negative effects on others. A time-aligned multitrack is not objectively better or worse than a raw one. All that matters is whether it sounds better to you. Some engineers use it routinely, others disdain it altogether, but before you can decide for yourself, you need to learn how to do it...

Make It Easy On Yourself

As I've just mentioned, time-alignment is done at the mix stage rather than during recording. However, if you anticipate that you might want to use it, it's helpful to document your mic placement through photos and measurements. What can also save time at the mix is making the effort to capture an isolated, transient signal from every source position that you might want to correct. The key visual reference for setting up time-alignment is the waveform display in your DAW, but this is only useful if you can identify the same event on all the tracks that have captured it. That's fairly easy with an isolated snare hit, but it's impossible with, say, a legato bowed violin note with lots of spill. Hence it can be useful to get each musician to record a handclap or similar.

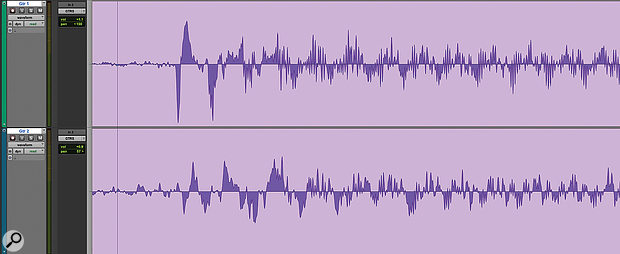

The snare top and bottom mics have produced quite different waveforms, but there's enough visual information here to suggest that reversing the polarity on the bottom mic and moving it a few samples ahead might create a better alignment.

The snare top and bottom mics have produced quite different waveforms, but there's enough visual information here to suggest that reversing the polarity on the bottom mic and moving it a few samples ahead might create a better alignment.

The waveform of any event will be markedly different on all the mics that have captured that event, and will be 'upside down' on any mics that have captured it in opposite polarity. If you can identify an initial transient or a prominent zero crossing in all of them, you have a visual reference that can be used as a starting point for time-alignment. (If, on the other hand, the waveforms are so different that the same transient can't confidently be identified in all of them, time-alignment might not make much difference in any case.)

The next step is to try to measure the time difference, and some DAWs make this much easier than others. In Pro Tools, for example, it's dead simple. Set the main time base to be Samples, click on the transient point you've identified in one on of the tracks, then Shift-click on the same point in the other track. By doing this, you're making an edit selection that's exactly as long as the time difference between these two points. Pro Tools will helpfully report the length of this selection in the units of the chosen time base (in this case, Samples) in the main toolbar. Several other DAWs allow a similar approach, though I can think of at least one which makes this apparently simple measurement needlessly difficult! (Even then, with enough persistence it should be possible to get at least a ballpark figure.) This figure can be cross-checked against any information you have from the recording session, to make sure it isn't wildly out. For instance, if you measure the difference between the overhead and snare mics as being 500 samples, either your measurement has gone wrong or the tracking engineer had some very tall mic stands.

Stitching Time

Once you have a clear idea of the difference in time of arrival between the same event in two or more tracks, you can 'correct' for it. Usually, the aim is to close the gap, so that each event in the close mic plays back at exactly the same time as it does in the distant mics, rather than fractionally earlier. The obvious way to do this is by sliding regions on the close-mic track slightly to the right in your DAW. I never use this method, because it's all too easy to get yourself into a complete mess, either by moving only one section of an edited track, or by leaving yourself unable to revert to the unmolested version when you realise it's not working. You can't easily A/B the 'corrected' against the uncorrected version when using this approach, and nor can you easily listen to the results of these actions as you're doing them.

Sometimes inspecting the waveform reveals no obvious starting point for time-alignment, even in cases like this where the same guitar has been recorded through two amps.

Sometimes inspecting the waveform reveals no obvious starting point for time-alignment, even in cases like this where the same guitar has been recorded through two amps.

My preference is to use a specialised delay or time-adjustment plug‑in instead. Pro Tools comes with the free Time Adjuster plug‑in, which allows you to enter a delay value in samples either through text input or by moving a slider. Better still is Eventide's inexpensive Precision Time Align, which has coarse and fine delay sliders, permits negative as well as positive delays to be entered, and allows the delay time to be specified to the nearest hundredth of a sample. It also gives you a very useful read-out that translates the sample delay into the distance travelled by sound in that time. A similar tool, Forward Audio's faTimeAlign does a similar thing, and has some innovative grouping functions. Voxengo's freeware Latency Delay also enables you to specify a negative delay (in whole samples).

Eventide's more sophisticated Precision Time Align plug‑in has a number of additional extra features and can even implement sub-sample delay times.

Eventide's more sophisticated Precision Time Align plug‑in has a number of additional extra features and can even implement sub-sample delay times.

Alternatively, some DAWs will allow you to enter a delay as a track parameter; this works, but these parameters are usually quite obscure and easy to overlook when you later recall the session, and once again, it doesn't give you the same freedom to do quick A/B comparisons you can exercise by bypassing a plug‑in.

The time-alignment settings you arrive at by visual inspection of the waveform are just a starting point. A plug‑in with a slider, especially one that offers very fine control, allows you to fine-tune these settings by ear, and it's essential to do this. A trick that might (but might not) help you when aligning two tracks is to invert the polarity of one and listen for the point at which you notice the most phase cancellation — which can sometimes be easier to listen out for — and then flip it back; this should get you somewhere close to the optimum relationship, though you may still want to refine things.

As I've emphasised throughout this article, time-aligned multitracks aren't intrinsically more or less 'correct' than raw ones. We never simultaneously hear the same thing from close up and far away in real life, so there's no natural reference point. The only criterion that matters is: does it sound better? That's a purely subjective choice, and it's one that you need to be quite careful about. It's all too easy to focus blindly on the snare sound and thus ignore the fact that the hi-hat has gone phasey and swimmy, or to achieve results that sound 'bigger' in stereo but thoroughly nasty in mono. But, caveats acknowledged, it's a technique that I personally use quite often, and one which, to my ears, can improve the subjective sound of some multi-miked recordings.

It's all too easy to focus blindly on the snare sound and thus ignore the fact that the hi-hat has gone phasey and swimmy, or to achieve results that sound 'bigger' in stereo but thoroughly nasty in mono.

It's A Hit

The most common and most obvious use case for time-alignment is on drum-kit recordings. There are actually several quite distinct possibilities here, some more widely used than others:

Overhead mic alignment. Alignment can sometimes help correct badly placed stereo overhead mics. When you solo the overheads on their own, you'd expect to hear the kick and snare drums close to the centre of the stereo field, with the other drums and cymbals in logical and clearly defined positions to the left or right. Occasionally, though, you run across recordings that have inexplicably been made with one overhead mic much higher up than the other, or with too great a distance between them. Sometimes the best take happens to be the one where the stand drooped and no-one noticed. In these cases, I often end up simply scrapping one of the overheads and using the other in mono, but it's definitely worth trying time-alignment to see if you can improve matters. The aim here is to align one of the overheads with the other, so that the kick and/or snare arrives at the same time in both. Be sure to audition the results in mono, though.

Increasing the apparent size of the room. This is a trick often credited to engineer Steve Albini, the idea being that instead of closing up the time difference between the overheads and the room mics, you amplify it by delaying the room mics still further. Conceptually, it's similar to using pre-delay on a reverb plug‑in. For me, this falls into the category of things I've often tried and never liked, but it's easy and painless to experiment with.

Getting two close mics on the same drum to work together effectively. It's common to record snare drums with top and bottom mics, and likewise to complement a mic inside the bass drum with one outside. Some engineers also like to mic toms top and bottom, or to mic the side of the snare. If the mic placement wasn't spot-on, time-alignment can help you to get the most from this potential reinforcing effect (in most cases, one mic will require polarity reversal if it wasn't done at tracking). Note, though, that the alignment that delivers the best sound for each drum might not be the one that looks the most perfect, especially in the case of the bass drum.

Minimising the effects of unwanted drum spill on other mics. In a live recording, every mic in the room will pick up the drums to a greater or lesser extent. This can be a real problem, especially when you have several vocal mics open. All will typically be acting as bad-sounding, unwanted room mics, and the cumulative effect can turn a tight drum sound into a complete mess. Shifting these vocal tracks slightly to the left so that the drum spill on them is more closely aligned with the actual drum tracks can improve things, though the benefit is usually quite limited.

Time-aligning the close mics against the overheads. This is the most common application of the technique, and also the most controversial, perhaps because it isn't straightforwardly corrective in the way that the others can be. There are certainly compromises involved. One is that every close mic used on a kit will pick up spill from the other elements of the kit. Time-aligning a close mic will thus change the phase relationship between the spill on that mic, the overheads, and the spill on other mics, potentially affecting the sound of the whole kit. If a spaced pair was used, there will also be a time difference between the two overheads for things like floor toms and hi-hats that are off-centre. In these cases it's probably best to align them to the earlier and thus closer of the two overheads.

In my experience, the effect of this sort of time-alignment is somewhat like that of a transient enhancer. Drum hits appear a little more focused and cut through the mix a bit more. Once again, it's vital to audition the effect both in mono and in the context of the full mix. I sometimes find it a little unnatural in isolation, but a useful source of extra impact in context. Sometimes I'll try it and decide against it, but more often than not, it stays.

Time-alignment is not a universal panacea. Neither is it a substitute for getting things right at the recording stage. It is always a compromise.

I Think We're Aligned Now

Drums aren't the only instrument for which time-alignment can be put to good use. Fierce debates erupt in the classical music recording fraternity as to whether spot mics on individual sections or instruments should be time-aligned with the main stereo pair or Decca Tree. The considerations are much the same as with drum close mics and overheads, but on a larger scale. If you plan to try this, bring a tape measure to the tracking session, as it can be impossible to identify suitable transients in the waveforms to time-align them by eye.

Another classic case is when you have the same instrument recorded using both a DI and a microphone, as is often done with guitars, electric pianos, basses and the like. When you zoom in and inspect them, the DI'd signal invariably appears slightly ahead of the miked one. Often, the two waveforms will also differ in shape, meaning there isn't an obvious starting point for a delay value. You really do need to use your ears to find the best setting. There's no natural reference here as to what it 'should' sound like, only what you find pleasing. If you're using the DI track as fodder for an amp simulator or other heavy processing, make sure to audition the results with that processing in place.

Time-alignment can also be worth exploring when you're miking a singing instrumentalist and the vocal spills onto the guitar or piano mics, arriving slightly later on those mics than it does on the vocal mic. When the instrument and vocal mics are combined at the mix, the delayed vocal spill causes comb-filtering and coloration. Applying a short delay to the vocal mic can eliminate or minimise this timing difference, and perhaps reduce the coloration. A useful tip in this situation is to audition settings by focusing on a section of the recording that features only unaccompanied voice. Then you can turn the guitar or piano mics up to a point where the unwanted effects of vocal spill are obvious, making it easier to fine-tune the settings.

Once again, this is something that has to be done carefully. It's vital to check the results in mono, and to revisit them after you've applied any mix processing such as EQ or compression. The sorts of high-frequency boost that are typically used at the mix can expose all sorts of nasties that might otherwise have gone unnoticed! And, of course, be aware that you're not just manipulating the vocal sound here. You're also changing the relationship between the sound of the instrument as captured on its dedicated mic, and as captured as spill on the vocal mic, so any improvement you make in the vocal sound might well come at the cost of a worse guitar or piano tone.

Time-alignment can be a powerful tool — and with great power comes great responsibility, so tread carefully!

Automatic Alignment

Sound Radix Auto-Align — one of a few plug‑ins now available that can automate the process of time-alignment.

Sound Radix Auto-Align — one of a few plug‑ins now available that can automate the process of time-alignment.

As with most tedious manual processes, clever plug‑in developers have come up with ways to automate time-alignment. Probably the best-known tool for the job is Sound Radix's Auto‑Align, which is said to "automatically detect and compensate for the delay between the microphones sample-accurately". Similar claims are made for MeldaProduction's MAutoAlign.

Phase Rotation

Time-alignment can be seen as an extension of the familiar process of checking and correcting polarity between multiple mics. Another extension of that process is 'phase rotation'.

Thanks to the work of French mathematician Joseph Fourier, we know that any complex sound can be thought of as being made up of simpler ones, namely sine waves at various frequencies and amplitudes. In essence, what phase rotation does is to change the phase relationships between these sine waves, without affecting their amplitude or frequency. The effect on a single track in isolation is usually subtle and often undetectable. What does change is the pattern of reinforcement and cancellation that takes place when that track is combined with other mics that have recorded the same source. For this reason, phase rotation is another tool that can sometimes help to get multi-miked recordings to sound more coherent.

There are plenty of phase rotation plug‑ins (also known as all-pass filters) on the market, including UA's Little Labs IBP, Waves' InPhase and Voxengo's PHA-979. More sophisticated options include Melda's MFreeformPhase, which allows you very precise control over phase at different frequencies, and both Sound Radix's Pi and Forward Audio's faGuitarAlign, both of which automate the process of finding the optimum relative phase between different tracks.