If you're looking to release a record that you've produced at home, it's a good idea to have the product professionally mastered, but it's not always obvious if a mix is adequately finished. We find out how to prepare your songs for the mastering house, and what the engineer can do for you.

One of the questions Sound On Sound is asked by its readers most frequently goes something like this: 'Why don't my recordings sound as polished as a commercial record release?' The answer usually given is that the difference is probably a result of the mastering process, which tends to give recordings a cohesive and professional feel. It is understandable that so many people are confused, however; after all, most of us never get to hear the unmastered version of a record fresh from the mixing engineer's studio, so it remains a mystery what the pre-mastering mixes originally sounded like. Obviously professional mix engineers soon get to know what is required by the mastering house, but how does the humble home studio owner prepare their work for mastering?

In the following pages we'll find out by talking to a top mastering engineer. We'll also be discussing important formatting and financial issues, and finding out what to expect when attending a mastering session. While this article will deal with the issues arising during the preparation of an album ready for mastering, there'll also be an article next month where I'll document a day with the mastering engineer during a genuine recording session.

Case Study

Like a typical SOS reader, I've been recording and producing an album at home in a flawed acoustic environment using less than perfect monitoring and some budget gear! Most of the vocals, and the majority of the guitar parts, were recorded in a small box room sporadically lined with segments of acoustic foam and thick drapes. The rhythm section, organ sounds, and piano parts were mainly sourced from sound modules and therefore didn't pose too many problems. Mixing was done in an altogether larger room, measuring a little less than 4 x 4m. Once again, the acoustic treatment was rather makeshift and inexact, and was partly taken care of by soft furnishings, book shelves, and clutter! Structures like the fire breast and doorways helped disperse some potentially nasty reflections, but the wooden floor was not ideal, due to its tendency to resonate along with the bass.

For monitoring my mixes I used a pair of B&W DM303 speakers, which, although designed for hi-fi use, are known for their fairly neutral response. I constructed a set of speaker stands to reduce vibrations travelling to the wooden floor, and positioned them 0.5m from the back wall as recommended in the manual as a way of avoiding bass reinforcement. I couldn't quite get them the recommended 1.5m apart because of the location of two doors, but I placed them as far apart as possible in order to get a decent stereo image. In my mixing position I was seated on a large futon just beyond the centre of the room, so that my ear level was approximately in line with the monitors.

For the example project, mixing was carried out in a typical home-studio environment, with little in the way of acoustic treatment. However, consultation with the mastering engineer during the mixdown process ensured that the final mixes would respond well at the mastering stage.

For the example project, mixing was carried out in a typical home-studio environment, with little in the way of acoustic treatment. However, consultation with the mastering engineer during the mixdown process ensured that the final mixes would respond well at the mastering stage.

All mixes were double-checked through a pair of Sony MDR7509 headphones, which deliver quite a good level of bass, and I did some A/B testing with some JVC hi-fi speakers. The dramatic difference in sound between the different monitors convinced me that I could not be certain of determining the most honest sound, so I tried to make sure each track worked well on the better monitors primarily, and didn't suffer at either very high or very low listening levels. Although I felt confident that I had tested my mixes fairly thoroughly, I still couldn't guess how they would sound after professional mastering, and I had no way of being certain that the room wasn't skewing my perception.

My chosen mastering engineer was Ray Staff at Alchemy Soho, in London. Picking the right engineer is a hard task, as it is difficult to guess what a record sounded like before it was mastered, and therefore impossible to assess what has been done by the engineer! I was lucky enough to know an experienced producer who could recommend a few people to me, and Ray was top of his list.

Costing The Job

For many people, price will be one of their main criteria for deciding whether to use one mastering service over another. Charges do vary a great deal, but a CD album typically costs somewhere between £900 and £1800 including VAT in the UK. Surround and vinyl masters differ considerably, and will need to be budgeted for separately. It's also worth noting that mastering houses tend to quote their prices excluding VAT, so it's worth clarifying this before the session if you're not VAT registered.

In most cases, though, mastering services are charged by the hour, so it is not always certain how much a project will eventually cost. Ray Staff explains: "An average album will take about a day's work, but how much that costs still depends on the length of the session. It could be eight or ten hours work. Sometimes I'll work on a record for a couple of days because there are so many bits to EQ or marry up. That's often because of differences in sound where people have worked in more than one studio. You can also find that a mix done in the middle of the night can sound very bright whereas another done during the day is fresh and sweet, but you've got to make them sit side by side. Until you get going you just don't know." Tom took preliminary mixes to Ray Staff at Alchemy Soho, who advised him on how to complete the mixing for the best mastered results.

Tom took preliminary mixes to Ray Staff at Alchemy Soho, who advised him on how to complete the mixing for the best mastered results.

There are a number of services advertising on the web which offer cheap mastering for small labels. Most allow tracks to be sent for mastering via email, either one at a time or as part of an album project. Paying a little bit more for a more personal service may well be worthwhile in the end, though, largely because being present at the session is the only way to interact with the engineer. It also enables you to see what equipment is being used and who is doing the work.

I asked Ray what factors might account for the large differences in price between budget mastering jobs and the more expensive ones. "If someone is offering to master an album for £300, there will be a reason. It is not unusual for us to get calls from someone saying that the record company has sent it to somebody who thinks they are a mastering engineer because they have a PC at home. The artist has ended up being disappointed with the result and have come here to have it all done again. Some places use cheap equipment, software, and plug-ins, and bosh stuff up very quickly, breaking all the quality rules in the process.

"This is particularly the case if you want to release your album on vinyl, because your engineer needs to have the relevant experience. I have often received masters prepared without this experience and they are totally unacceptable. There are many things that contribute to a good vinyl cut and they all have to be addressed. Some mastering companies, such as Soundmasters, offer a remote mastering service, where you send and receive the audio files over the Internet. While this approach is undoubtedly convenient, you'll miss out on observing and interacting with the mastering engineer during the session.

Some mastering companies, such as Soundmasters, offer a remote mastering service, where you send and receive the audio files over the Internet. While this approach is undoubtedly convenient, you'll miss out on observing and interacting with the mastering engineer during the session.

"To do a good job for CD mastering you have to know how to hook up digital equipment properly, understand things like clocking and dithering, and how to increase levels while avoiding distortion. Digital is always sold as something that is perfect, but there is good digital and bad digital, as well as cheap and expensive digital. Off the top of my head, I can think of only three or four digital equalisers that I would say are OK. I also have a bee in my bonnet about people sending stuff to the factory on CD instead of using DDP format on Exabyte tape. To me, most CDs manufactured from a master CD sound crap, but that is the only format many of the cheaper places can give you."

Getting Started

Knowing that my room at home was quite likely to have uneven acoustics, I wanted to find out from Ray if there were any tests I could conduct to establish if my mixes were reasonably well balanced. Ray explained that unless I had a properly calibrated or acoustically treated room set up by a specialist, I could never be certain that my mixes would be free from problems. As few home studios have neutral acoustics, Ray allows people to send him tracks at the start of the mixing process so that they can be demoed on the mastering setup. He is then able to provide some sort of feedback and advice wherever necessary.

"The pitfall in doing that though," warns Ray, "is that other songs can have a completely different spectrum to the ones sent to us. For example, the person mixing may have a big hole in their monitoring at 60Hz which has not affected anything in the sample song. If the next tracks have a bass guitar around that area then they could find themselves boosting those frequencies so that when it gets here everyone is wondering where all the extra bass has come from. So you can't be certain if the rest of the tracks will sound fine, you can only generalise and say that things seem about right.

"There are one or two people who have sent stuff in to ask our opinion prior to a mastering session who have subsequently gone away and mixed things differently. Recently, a chap brought in a recording that was so over-compressed that I had to say to him that there was not a lot I could do with it, but as the project was still in the recording process, he took it back to the studio, recalled the settings, and reduced the processing to make a nicer-sounding mix."

Format Issues

If your recordings have been made at 16-bit, 44.1kHz, you may be tempted to edit your songs into the right order, and burn them as CD Audio. However, as Ray explains, there may be some quality issues to consider: "If you have a choice of saving your recordings as some kind of file such as WAV, AIFF, or Sound Designer II, rather than as CD Audio, I promise you that the file will sound better every time, because CD Audio is inferior in many ways. It doesn't matter what word length or sample rate the file has, it is still a superior format. Of course you are restricted to 16 bits with CD Audio, so if you've recorded in 24 bit you'll have to dither down before mastering, and there can be problems with jitter and the error rate.

Here you can see the options in Roxio's Toast which allow you to set the format of CDs you burn. ISO9660 is the most widely compatible format, so this is a good choice when you create CD-ROMs for sending final mix files for mastering.

Here you can see the options in Roxio's Toast which allow you to set the format of CDs you burn. ISO9660 is the most widely compatible format, so this is a good choice when you create CD-ROMs for sending final mix files for mastering.

"Most studios won't have a problem dealing with data files, although Sound Designer II files can sometimes cause problems because, as I understand it, they are designed to reside on a Mac-formatted drive. If you are being charged by the hour, you don't want to spend time trying to get the files to play back, so the best thing anyone with a Pro Tools setup can do is back everything up as AIFF or WAV files.

"Sometimes there can be problems when reading disks, but if data is recorded onto a standard ISO9660-format CD-ROM it is usually readable by anything. If you're coming from a PC you shouldn't have any problem bringing files to us, for instance, but from a Mac you have to ensure that what you bring is PC compatible. In Roxio's Toast for example, there is a button that just says Make PC Compatible.

"Whatever the delivery format, though, you've got to start with the highest possible quality and work down. You can only extract or manipulate the sound well if it has a respectable sound in the first place. It's hard to start low and then downsize to MP3 and expect a good result."

Spotting Mistakes

Although I'd spent many hours mulling over the relative levels of the various elements in my mixes, I wanted to know what sort of mistakes were commonly encountered by a mastering engineer so that I could check that I wasn't making any of them! "It is not uncommon for domestic stuff to sound really hard, especially if it's been recorded in the digital domain," says Ray. "You might think that it is a result of people using domestic hi-fi speakers that are too flattering, but a lot of modern monitors already sound quite brash, so it's surprising that people don't back off the mid-frequencies a bit. I think it's probably because they are trying to enhance the energy of the track, but have gone about it in the wrong way. I recently had an album to do where someone had really boosted the 3-5kHz range on a couple of tracks, making them sound brash and edgy. The rest of the mix elements were fine, but I couldn't just take the 3-5kHz region down, because all the song's energy was mashed up in that one area. In that situation, reducing the mid-frequencies is almost the same as lowering the volume, so problems like that are really hard to fix at this stage."

One of the hardest things to judge in a home environment is the bass end. This is because it takes a greater mass of material to attenuate lower frequencies than it does higher ones, so filling a room with soft furnishings will help reduce the highs, and can help remove flutter echo, but it usually takes custom-made acoustic bass traps to effectively neutralise bass hot spots. What's more, when recordings are made in rooms with wooden floors there is the possibility that the entire floor may resonate in sympathy with the bass, making it sound relatively powerful in relation to the mid-range and upper frequencies. To a certain extent, the mastering engineer can be expected to take care of bass problems, but any processing does come at a cost, as Ray explains: "It's quite common to get recordings where one note is very dominant, especially on the bass around 60Hz or 70Hz, but if you try filtering it out with EQ or compressing the bass end, the process affects everything else in that area. For example, taking the bass down sometimes affects the low end of the vocal, drum kit, or it can take the body out of the guitars. I can usually tidy up very low-end rumble at 20-35Hz, but loud bass notes force you to make bigger compromises.

"Every time I try to tackle an individual instrument it's a compromise, because the whole mix is affected. Bass isn't the only problem, though — aggressive sibilance is also common. There is no one area where everyone makes a mistake. A lot of people haven't experienced working in a studio with an engineer on a variety of material. In their studio it's been sounding great so there is huge disappointment when they get to the mastering stage and it doesn't sound right. Sometimes professional studios don't get it right either, though. It doesn't matter what kit they've got, just who's engineering. Good engineers with lots of experience often put things right so mastering is less fiddly. On the other hand, some small guys turn out really good work."

Ray Staff of Alchemy Soho mastering house.

Ray Staff of Alchemy Soho mastering house.

The Mix As A Whole

Apart from problematic frequencies within the mix, there is also the question of how the entire mix should be treated prior to mastering. I wanted to know if there were any processes I should apply to the stereo buss that would enable me to test if my mixes were actually finished enough for mastering. Ray: "I don't have a general rule because my choice is always designed to suit each individual song, and the style of music that's playing, and that's a matter of experience. Compression changes the sound and musicality of what you've got, so it has to be selected properly to be really effective.

"One thing I would say though is not to use too much compression. A lot of people working in the modern era tend to over-process their audio, but if something is over-compressed it will be too dense for us to manipulate further. You can only compress so far before it starts to take the energy out of the track and then everything starts to sound quiet. Before using a compressor you have to ask yourself why you need to use it, and what it is going to achieve. If compression raises the level, it's worth taking the master volume down to the level of an uncompressed file in order to compare the sound of the two to see what it is really doing, and if it is worthwhile. Originally, compression was used a lot on bass guitars because bass can go everywhere if it's not controlled, and that's a good reason for using it, but you still need the right kind. If it's not appropriate, don't do it."

"It also pays to avoid normalising everything up to maximum level. There's no need to be hammering the end scale, so I suggest that people simply mix to a sensible level and don't normalise at all. It's not so problematic if I'm feeding a digital signal straight into the analogue domain, because I have to control the level anyway, but if it's staying within the digital system and it is very loud, the first thing I have to do is take the level down to regain some headroom, otherwise there's no space for adding a little bit of bass or top.

"Experienced engineers usually provide us with two mixes, one without any mix compression and one where they've compressed for listening purposes, just so they've had something that's a bit louder. Most just use a limiter plug-in like the Waves L2 Ultramaximizer and apply 2-4dB of lift. Having the two versions gives us the opportunity to take the uncompressed version and work on it further."

Supply & Demand

Apart from getting the music sounding right, it is just as important to supply the mastering engineer with the right information so that they can proceed with the job satisfactorily. Certainly any audio files sent to the mastering house prior to the session require detailed labelling so that they can be properly identified, but anyone attending a session also needs to have all the necessary information to hand. If ISRC codes are being used then, in the UK, these need to be obtained from Phonographic Performance Ltd (PPL) in advance, so that they can be allocated to each track at the end of the session. Ray explains what else is and isn't needed. "We don't need to know lyrics, just song titles and labelling to tell us who owns the project and who's the artist. It is not unusual to get given a CD that just says 'Masters', and in a place like this where there are hundreds of CDs flying around, that's really inadequate. The running order we do need to know. We can amend it, but it is much more cost effective if someone has sat at home and made the decision beforehand. Every time you make a change it will delay proceedings and/or cost more money." If you're wanting to use ISRC codes to track the broadcast use of your music in the UK, then you'll need to apply to Phonographic Performance Ltd (PPL) for these — in the first place you might want to use their web application form.

If you're wanting to use ISRC codes to track the broadcast use of your music in the UK, then you'll need to apply to Phonographic Performance Ltd (PPL) for these — in the first place you might want to use their web application form.

There are also the all-important gaps between songs to consider. "Normally, I prefer people to attend the session and listen to the gaps for themselves, because opinions can differ. I've had people send me an unmastered CD saying that they've worked out all the gaps, so I've read their CD's Table Of Contents to get their timings, and matched mine up exactly. After hearing the master they've then decided that the gaps don't sound right. That's because they're hearing different detail, or because my fades are smoother making it sound different. If someone says 'I prefer my gaps tight', then that's fine, because I have a yardstick to work from, but there is no substitute for attending the session to confirm how the gaps sound.

"On the day we get them as good as we can, but you can only really be sure when you've sat back and listened through a couple of times. It's funny how gaps seem to vary according to what mood you're in. It's not unusual for people to say 'start the next one there' straight after the previous song has finished, and that's because they're not relaxed and are sitting there in anticipation. They often end up calling back later asking if we can add another second to every gap. If you have two energetic songs together you might place them straight after one another, but you might need a longer gap between a big lively song and a moody one, so you have to listen on a musical and emotional level, and do what feels right. Most mastering engineers are used to doing it and do it reasonably well."

Compare & Contrast

In an ideal world, the artist or producer would have time to sit down with the mastering engineer and discuss how the energy of each song is supposed to ebb and flow, as well as how every track relates to the others on the album. Of course, such a discourse would prevent the mastering engineer from getting any work done at all, and it would end up costing a fortune! Ray explains what can be done, though. "I advise people to bring a couple of CDs they know well so that they can listen to them in this room and get used to the environment. Not only does that help them feel comfortable in the studio, but it also gives me an idea of the sort of thing they are trying to emulate. The music has to be something they know and love, and perhaps something they are aspiring to sound like. Obviously if they've got a home recording that they want to sound like U2 then it isn't going to get there. I've had a couple of people who wanted the stuff they'd recorded at home for £5000 to sound like Anastacia, when she's probably spend $300000 making her album. I can't give them that quality, but I can take them in that direction so that it sits in the same stable."

Preparing The Ingredients

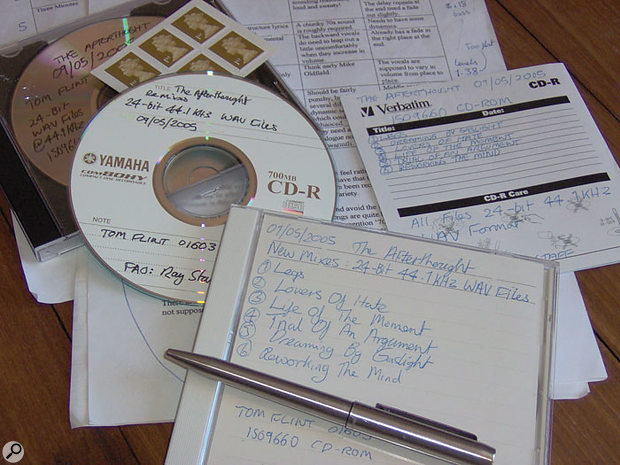

After taking into account Ray's advice, I completed my final mixes, burnt them as 24-bit WAV files to a CD-RW disc and transferred them to my PC where I could gather them together in a folder. The total size of all the tracks was larger than the capacity of one CD, so I split them into two groups. In Easy CD Creator I selected the option for creating a data CD-ROM and set it from Joliet to ISO9660, to be absolutely certain that it was going to be compatible with Ray's system (see the 'Formats Issues' box elsewhere in this article).

Mastering houses are inundated with CDs labelled 'Masters', so make sure to include as much relevant information as you can on your own CD-ROMs — CD/file formats, sampling frequency, bit depth, project name, track listing, and contact details can all be useful.

Mastering houses are inundated with CDs labelled 'Masters', so make sure to include as much relevant information as you can on your own CD-ROMs — CD/file formats, sampling frequency, bit depth, project name, track listing, and contact details can all be useful.

On the body of each CD-ROM, I wrote my name and telephone number, the band name, and the date. I also added information about the data saved onto each CD. I included the number of songs, the format, and bit rate, and the fact that they were saved in ISO9660 format. I repeated the same information on the jewel case's paper inlay, together with a complete list of the songs. I made sure that the CDs were labelled '1 of 2' and '2 of 2' so that it was clear they were together.

I posted the lot to the mastering house together with a covering letter explaining the content, and then followed up the posting with a phone call to let Ray know the recording was on its way. We agreed that I would phone back in a few days, giving him a chance to listen to the material. In case he didn't have time to check each file, in the covering letter I had highlighted one key track which I thought was representative, but when I rang back it turned out that Ray had actually listened to a snapshot of each track.

Fortunately there seemed to be no formatting problems and Ray felt the mixes were 'quite pliable' and in a state from which he could make them sound pretty much how I wanted. I had deliberately left off any mix-buss compression or EQ so that he would have more to work with, so I was glad to hear that this had turned out OK. The next step was to book a day for the mastering session, which was simply a matter of phoning the studio, giving my details, and making sure that Ray was working that day. In the mean time, I planned to revisit a couple of the mixes, slightly alter a few fader moves here and there, and take the results to the mastering session on a new CD-ROM.

Stay Tuned...

Next month, I'll take a look at what actually goes on during the mastering session, and find out how a humble home-mixed data file ends up fully mastered on a medium ripe for the pressing plant.