Continuity

After prolonged editing and adding overdubs, Moffatt spent a lot of time rough mixing the songs, before releasing them to Cooley to do the final mixes. "I push the songs into the general direction of where I think they need to be," says Moffatt, "to the point where the mixes sound good in my opinion. Jim then makes them sound great. He really ties everything together and does a wonderful job of making what I did shine. He sometimes uses my plug–ins and will embellish them, for example pushing the vocals more up front and making them sound fuller. And sometimes he does something totally different. In general, he's great with dynamics and using compression to unify the track. He also adds reverbs and all that stuff, and continually pushes the largeness of the tracks. He really does have a massive impact. The other thing that's great is that I get to go into the studio with him when he finalises mixes. With other mixers I might not get that opportunity."

"Once Scott had the songs to a point where they were ready to be mixed," continues Cooley, "he'd send me the Pro Tools session, and sometimes also a rough mix. If he didn't send me a rough, I'd print it from the session he sent me, and I'd load it back into the session for reference. He always has the vibe pretty hammered out, so it's a starting point I don't want to stray too far from. I then take about a day to mix the song. I continue until it feels good, and then I get away from it. The thing about mixing in the box is that you can easily shift between mixing different tracks. Five to six days later he'd send me another song to mix. We did it like that, one at a time. Once we had all the mixes ready for the final tweaks, he'd come over, and we tweaked things together for a couple of days. In fact, there are a couple of songs that we fully mixed together."

Boxing Clever

The room where Cooley mixes, sometimes with help from Moffatt, is very 21st century, in that it's pretty small, and he works entirely in the box. "I have one of these Mac 'trash cans' and an Avid HDX system, plus two UAD Octo cards, and billions of plug-ins — pretty much every one you can think of! My soundcard is the Avid HD Omni, and I have a BlackMagic MultiDock, allowing interchangeable solid-state hard drives. I also use the SPL MTC 2381 Stereo Monitor Controller, and NHT A20 and KRK E8 monitors. Chuck Ainley got this pair of NHT monitors years ago, and I just love them. They are very flat and true, and don't over-hype. I use my KRKs mainly for tracking. For whatever reason they sound better in big rooms, and they don't sound good in my room. It may be fairly small, but it's acoustically treated and has a high ceiling. In my experience the low end never sounds right in rooms with low ceilings.

"I grew up with SSL desks, and I have mixed many projects on them. I am familiar with working in that world, and it's why I use many SSL channel strip plug-ins, particularly on drums. They add punchiness. But if someone gave me the choice and the budget to mix on a desk, I'd still prefer to do it in the box, because I'm totally comfortable working that way. It'd take longer to do a mix on a desk, and it'd be much harder to recall. The plug-ins have become really good at recreating the analogue sound, especially the UAD ones, and then you have, for example, the FabFilter plug-ins that completely reinvent things. I feel fortunate, however, that I came up during a transitional time and learned how things work in the analogue domain, so I can apply that knowledge in the box. Many people have said that my in-the-box mixes sound analogue, and I attribute that to the fact that I learned in that world."

Jim Cooley: "If someone gave me the choice and the budget to mix on a desk, I'd still prefer to do it in the box, because I'm totally comfortable working that way. It'd take longer to do a mix on a desk, and it'd be much harder to recall.

Cooley has been at his room at Black River for five and a half years. He has an assistant, "who will prep mixes for me, and will do things like making stems, and printing different mix versions. These days everybody needs stems after I finish a mix. For the rest I'm pretty hands-on with the mixes. I check out the rough, and the instruction will be: 'Keep the vibe, just make it a bit better.' Or I may be told: 'Just do your thing.' But a lot of producers are great mixers, and they will give me tracks that are badass, and I just want to make it a little better. The Pro Tools sessions they send me are basically the rough, and when working on them I don't use a template but carry on in their session from where they left off. In a situation like that I am just totally leaning on my ears.

"I have very loose templates for other situations. They basically are based on songs that I have mixed in the past that are similar. So my templates are just an accumulation of things. If I use a past song as a template, I'll do the Import Session Data command with the tracks that match up to some degree. I also have made many track presets, which you can do in Pro Tools since a couple of years, and while you are working in a session you import them individually. I have good starting points for acoustic guitar, or kick drums, or overheads, or parallel compression tracks. I feel that if I leaned on straight-up templates, I'd put myself in a corner. I'd just get one type of sound. As I said, I prefer to be adaptable, in many ways.

"I also don't have a set way in which I approach a session. In general, I'll start with mixing the chorus, because that's ultimately where you're going. So, I'll get that to feel killer, and I'll then work on the verses. But the way I get there varies. Sometimes I will have everything up, and mess with that. Sometimes I'll start with the drums and bass and get these rocking. It's what I did with 'Beer Never Broke My Heart', because I felt that song needed to be slamming on country radio, and it needed punchy drums, big guitars and a big vocal. In that case I get the drums and bass to feel pretty solid, and then I'll rough in the guitars to where I feel they are pretty close. At that point I bring the vocal in to see where it's setting relative to everything else. The vocal is the centre point that defines where everything else needs to be, so I try to not to go too far with mixing before I know where the vocal is going to sit. Sometimes the track is too aggressive, and I have to dial it down a bit to get the vocal popping. Once I get to the point where the vocal is sitting pretty good, I will leave it alone for a bit, and I'll work on the track, and then I bring the vocal back in."

On The Beer

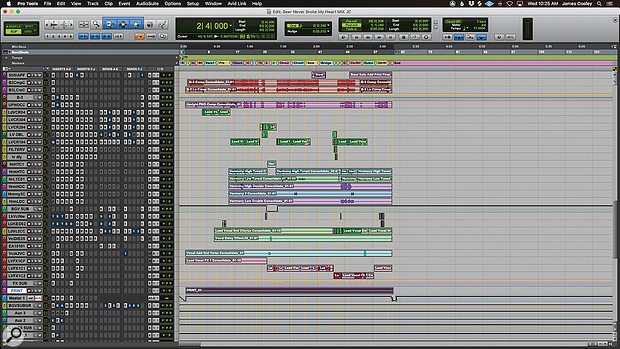

![These three screen captures show all of the audio tracks in Jim Cooley's mix of 'Beer Never Broke My Heart'. As you can see, many of the parts have been split out to multiple tracks for different treatments. [See sidebar to download a ZIP file containing hi-res versions of these screens to view greater detail.] These three screen captures show all of the audio tracks in Jim Cooley's mix of 'Beer Never Broke My Heart'. As you can see, many of the parts have been split out to multiple tracks for different treatments. [See sidebar to download a ZIP file containing hi-res versions of these screens to view greater detail.]](https://dt7v1i9vyp3mf.cloudfront.net/styles/header/s3/imagelibrary/I/IT_02_20_03a-dSJIhqLI7MhPSxZZalKTGJDAqllPm9PA.jpg) These three screen captures show all of the audio tracks in Jim Cooley's mix of 'Beer Never Broke My Heart'. As you can see, many of the parts have been split out to multiple tracks for different treatments. [See sidebar to download a ZIP file containing hi-res versions of these screens to view greater detail.]

These three screen captures show all of the audio tracks in Jim Cooley's mix of 'Beer Never Broke My Heart'. As you can see, many of the parts have been split out to multiple tracks for different treatments. [See sidebar to download a ZIP file containing hi-res versions of these screens to view greater detail.]

'Beer Never Broke My Heart' is the lead single from What You See Is What You Get. A hard-hitting, funky, country-rock track, it's a good example of the '90s-meets-2019 vibe that permeates Combs' music. The Pro Tools session is a whopping 143 tracks in size, and is very rich in plug-ins; some of the vocal tracks hit the full complement of 10 plug-ins in the inserts and 10 sends.

![]() luke-combs-protools-screens.zip

luke-combs-protools-screens.zip

One notable aspect of the session is the enormous number of aux tracks, including five parallel compression auxes and some 40 further aux tracks, mostly for effects. Below the parallel compression tracks are two percussion tracks and two loop aux tracks, but other than that the structure of the session is fairly conventional, with drums, two bass DI tracks, acoustic guitar, banjo, electric guitars, lap steel, B3 organ, piano, vocals, backing vocals, and finally a master track and a mix print track.

"This session was not as big as this when it came to me," says Cooley. "I break up the tracks a lot over several other tracks, to have different treatments for different sections. This obviously makes the sessions bigger. I like having options to send things to, so I create many of aux effects tracks. I'm not using them all though. But yes, it can get pretty crazy!

"I don't recall what template I used for this song, but, having worked with Luke before, I had done stuff that's similar, so I knew which way to go. I probably dug out a template mainly for the drums from a song that was somewhat similar, and perhaps also used a vocal chain that I had used on another Luke song, and that provided a decent starting point that I could tweak. My aux effects and parallel compression tracks also were from templates. I don't know why I got used to putting some of the parallel compression stuff at the top of the session. There's parallel compression for the percussion loop, keyboards, snare, percussion reverb and vocals. They all have similar chains, with the Waves TG12345 compressor, and the low and high end being taken out with the FabFilter Pro‑Q3. I think in this song I'm only using the parallel compression on the vocal bus."

Drums

Slate's Trigger plug-in was used to augment the recorded kick and snare drum with samples."Because this track had to be really hard–hitting, I layered tons of kick and snare samples. I like Steven Slate's Trigger, because it is really solid and easy to use. The kick and snare were well-recorded, so I actually took the kick from the session and made samples out of them as well, to get punch without the leakage, and combined these with my samples. With the kick drum I have a punchy sample with lots of attack, and a kick with big bottom end, and one with more ambience, and so on, and I blend them as required. They are all serving a purpose that is accumulative.

Slate's Trigger plug-in was used to augment the recorded kick and snare drum with samples."Because this track had to be really hard–hitting, I layered tons of kick and snare samples. I like Steven Slate's Trigger, because it is really solid and easy to use. The kick and snare were well-recorded, so I actually took the kick from the session and made samples out of them as well, to get punch without the leakage, and combined these with my samples. With the kick drum I have a punchy sample with lots of attack, and a kick with big bottom end, and one with more ambience, and so on, and I blend them as required. They are all serving a purpose that is accumulative.

"The session had live drums, so I try to make it not sound too sample-like, and also to keep the feeling of the live drums. I stay pretty focused on making sure the phase is correct. The more stuff you throw in, the more chance of having phasing problems. Sometimes I move things in time, but mainly it is a matter of inverting the phase and back. There are a number of gate plug-ins in the session, in blue, where I was checking the phase, but in the end I did not use these plug-ins.

"I did the same process with the snares, again combining different types of snare sounds and blending them. There are snares with more crack, that sound thuddier, a snare with ghost notes, a snare with more room and no attack, the original snare, which had ghost notes, and so on. I used parallel compression with the 1176 to pick up all the ghost notes. If you create a good snare blend with the ghost notes, it makes the sample stuff sound more natural. Plus I have another snare parallel compression track at the bottom of the session, with the Plug‑in Alliance Elysia compressor.

A mono reverb chamber mic was given some width using the Schoeps Mono Upmix plug-in, and gated from the snare drum."There are a number of ambient drums tracks in the session: overheads, Crotch, Far Room, Room and Chamber. I put the Schoeps Mono Upmix on the latter, because the chamber track was in mono and I wanted it to be more stereo. I triggered this from the snare drum, so every time the snare hits it would open up the chamber. And then I put a FabFilter Pro‑G gate on it. The crotch mic is typically put above the kick drum, and pointing at the drummer's crotch, hence the name. I added the McDSP Futzbox, to crunch it a bit, as well as a FabFilter Pro‑MB and UAD 1176LM E compressor, and then I again put the Pro‑G on it, to make sure it doesn't just become noise. It's all about the balance between the punch you get from the samples and making sure the drums sound natural as well. You get the punch from the samples and the feel from the room mics."

A mono reverb chamber mic was given some width using the Schoeps Mono Upmix plug-in, and gated from the snare drum."There are a number of ambient drums tracks in the session: overheads, Crotch, Far Room, Room and Chamber. I put the Schoeps Mono Upmix on the latter, because the chamber track was in mono and I wanted it to be more stereo. I triggered this from the snare drum, so every time the snare hits it would open up the chamber. And then I put a FabFilter Pro‑G gate on it. The crotch mic is typically put above the kick drum, and pointing at the drummer's crotch, hence the name. I added the McDSP Futzbox, to crunch it a bit, as well as a FabFilter Pro‑MB and UAD 1176LM E compressor, and then I again put the Pro‑G on it, to make sure it doesn't just become noise. It's all about the balance between the punch you get from the samples and making sure the drums sound natural as well. You get the punch from the samples and the feel from the room mics."

Bass & Guitars

"I duplicated the bass guitar DI track, and added harmonic distortion with parallel compression using a UAD 1176. I also EQ'ed the bass using the UAD Pultec MEQ-5 and EQP-1A, mostly adding some mid-range to make the bass pop in the mix. I have similar plug-ins on the banjo and the acoustic guitar tracks. There's a [SoundToys] Decapitator on the banjo to crunch it a bit, so it sits better in the mix. There's again a UAD 1176 for subtle compression and gain, the FabFilter Pro‑Q3 is taking out low end and boosting high mids, and the [IK Multimedia] T-RackS is for limiting, just to keep the peaks in check. I like using that on acoustic instruments for that reason. The acoustic guitar has similar plug-ins, but without the Decapitator.

A complex chain of plug-ins was used to beef up the banjo and make it cut through the mix."There probably were only half as many electric guitar tracks in this session as there are now. I've pulled them over various tracks, with a guitar part for the verse, and for the chorus, and so on, which allows me to treat each section differently, while maintaining a consistent sound for each section throughout the track. I will be changing volume, EQ, delays, reverb sends, depending on the section. Doing it like this also somewhat minimises the need for automation, but there is still panning automation, volume automation, and so on.

A complex chain of plug-ins was used to beef up the banjo and make it cut through the mix."There probably were only half as many electric guitar tracks in this session as there are now. I've pulled them over various tracks, with a guitar part for the verse, and for the chorus, and so on, which allows me to treat each section differently, while maintaining a consistent sound for each section throughout the track. I will be changing volume, EQ, delays, reverb sends, depending on the section. Doing it like this also somewhat minimises the need for automation, but there is still panning automation, volume automation, and so on.

"I also use clip gain a lot, depending on how things are recorded. But you have to realise that automation and clip gain have different purposes. Clip gaining 3dB is not the same as turning the volume up 3dB. I also sometimes use the Avid Trim plug-in, instead of clip gain, or the Time Adjuster, which does the same thing. The chains on the electric guitar tracks in this song are similar, with the [Brainworx] bx_console SSL 4000 G playing an important role. I like the 4000 EQ on guitars, the mid-range EQ sounds great, as does the compression. On this song I also use a little bit of SoundToys Echoboy Jr, with saturation, to get that cheap tape sound, and a slight slap, to give it a little bit more depth. And then I am sending it to a reverb aux for some more depth."

Vocals

"I also pulled the lead vocal track over different tracks. My lead vocal chain starts with a little bit of EQ from the Pro‑Q3, then some distortion from the Massey THC stompbox plug-in, then some Pro‑MB multi-band compression taking out some of the low mids, a UAD 1176 compressor, and then several instances of the Waves Renaissance De‑esser. Not all songs are the same with Luke: there are definitely different treatments EQ-wise, song to song. In this track you could get away with his voice not being quite as thick–sounding, because there are many things happening around it. His verse voice would have been slightly thicker, because there is less stuff competing there with the vocals. I only take low end out of his voice with the multiband, whenever it hits. I am also adding some distortion to his voice via one of the sends.

Jim Cooley makes extensive use of Waves's Renaissance De‑esser on vocals. Of the two instances here, one is acting as a conventional de-esser while the other is addressing harshness in the 3kHz region.

Jim Cooley makes extensive use of Waves's Renaissance De‑esser on vocals. Of the two instances here, one is acting as a conventional de-esser while the other is addressing harshness in the 3kHz region.

"I'm using millions of Renaissance De‑essers. I just like it for some reason. There is one at the beginning of the vocal chain, and there are two at the end — one is straight up, and one in split mode where I'm taking out those specific, pokey frequencies around 3k. When it is hit hard, it ducks that frequency by 3dB. I do it more now with the Pro‑Q3, because since they have dynamic EQ you can set it to work only when those frequencies are really popping. You can get a little bit more detailed with the Pro‑Q3. The Renaissance is also great as a straight de–esser and I use that on vocals constantly, but for some reason I just like the way that it is smoothing out frequencies in split mode. I will use it on instruments that are really pokey as well, for example to take mid-range frequencies out of a guitar solo. Again, when it's in split mode it will smooth those out."

Jim Cooley: In general, I get my mixes to be pretty slamming. I give them to the mastering engineer as hot as I can get it!

Master Bus

"My master chain in this song consists of an EQ, the Waves SSL compressor, and the UAD Fatso plug-in, for that analogue sound. I'm also using the iZotope Ozone 7, for mastering. I like Ozone for country stuff that has real drums, but for more programmed/electronic stuff I prefer to use the FabFilter Pro‑L2. I have been using Ozone 9 recently, which I think is pretty cool. But I did not care for v8, it did not sound as good, I don't know why. The plug-ins on my two-bus changes a lot. Sometimes I will use the FabFilter Saturn to add some harmonic stuff, or the Black Box Analog Design if I want stuff to hit hard. In general, I get my mixes to be pretty slamming. I give them to the mastering engineer as hot as I can get it!"

All, clearly, in the service of getting his mixes to sound as big and aggressive and 21st century as possible. As Cooley says, it's like the "'90s on steroids"!

Jim Cooley

Jim Cooley in his mix room.Photo: Jackie Osborne

Jim Cooley in his mix room.Photo: Jackie Osborne

Originally from California, Cooley moved to Florida when he was 10. He started playing guitar during his teens, and while recording himself on a Fostex DMT8 digital multitrack and using drum machines he "fell in love with the recording process." He went on to study at the Conservatory of Recording Arts and Sciences in Tempe, Arizona, and moved to Nashville in 2001, when he was 21. He interned at Sound Stage Studios, where he was immediately engaged in making safety reels for recordings made on Sony 3348 48-track digital tape recorders. He went independent two years later, and spent his time further cutting his teeth at Groove Room Studios, and working for six years as the assistant to legendary engineer Chuck Ainlay. He also worked extensively with rock producer and mixer David Thoener.

"I still do tracking, but today 90 percent of what I do is mixing," he says. "I always wanted to do mixing, because I feel that it is the most creative part of engineering. I like the finality of it: when it is done it is done. I know there is mastering, but to me all the magic happens in the mixing. And I like doing all kinds of different things and remain malleable. I learned that from Thoener, who would switch gears for whatever the project called for. If I need to put my stamp on it, that is cool, and if not and I need to let it be, I am capable of doing that as well. At the end of the day, you are servicing the client."