In the first part of a new short series about Stereo Recording Techniques, we start by exploring the most important tools of all: your brain and your ears!

Despite all the contemporary enthusiasm for multi‑channel immersive audio, most people still listen to recorded audio in stereo, and this obviously means that understanding and mastering stereo techniques remains a core skill for everyone involved in recording and mixing audio. Astonishingly, it’s been almost 30 years since I last wrote at length about stereo recording techniques in the pages of Sound On Sound! But, while it’s true to say that the principles haven’t changed in the intervening years, fashions and preferences certainly have — so I thought it about time I explored this topic once again, in a short series of articles over the next few months.

Despite all the contemporary enthusiasm for multi‑channel immersive audio, most people still listen to recorded audio in stereo, and this obviously means that understanding and mastering stereo techniques remains a core skill for everyone involved in recording and mixing audio. Astonishingly, it’s been almost 30 years since I last wrote at length about stereo recording techniques in the pages of Sound On Sound! But, while it’s true to say that the principles haven’t changed in the intervening years, fashions and preferences certainly have — so I thought it about time I explored this topic once again, in a short series of articles over the next few months.

Why Stereo?

Before we get into practical techniques and practices, the first questions we must ask ourselves are: why bother to record in ‘stereo’? Just what is it that we’re actually trying to achieve? I think there are two answers to these questions, and while both are perfectly valid they have very different goals and necessitate very different approaches.

The role of ‘stereo’ in most popular music is generally as ‘ear‑candy’, delivering exciting spacious effects. Often, it’s a case of the wider and more obvious the stereo spread, the better. Precise stereo imaging and accurate placement of sound sources within a real acoustic space is usually unnecessary, and often even irrelevant in this context (although there are exceptions, of course). Consequently, this ‘wider is better’ strategy brings enormous freedom in mic choices, placements and techniques. A practical example is miking an acoustic guitar with one mic placed close to the neck/body joint and another (often a different type of mic) near the tail of the guitar, with these two mics panned hard left/right, giving a wide stereo effect. The Glyn Johns drum recording technique is another example of (often) mismatched mics placed to deliver a pleasing and spacious ‘effect’ — even though precise imaging of individual drum components within the set, both relative to each other and within the acoustic environment, is largely lost.

The role of ‘stereo’ in most popular music is generally as ‘ear‑candy’, delivering exciting spacious effects. Often, it’s a case of the wider and more obvious the stereo spread, the better.

In contrast, recordings of classical music (and most other acoustic genres, in fact) tend to require a far more realistic portrayal of the relative spatial positions of instruments and performers, usually in a stage‑like setting, and within a natural acoustic environment. Achieving that necessitates precise and rigorous microphone techniques which, in turn, are built upon a good understanding of microphone properties and a knowledge of how parameters such as mic polar patterns, capsule spacing and mutual angle, mic height and distance all interact and can be adjusted to create the desired stereo imaging and perspective.

So, in this short series I shall be exploring a variety of popular stereo microphone techniques that are typically employed to achieve ‘realistic’ stereo recordings, as well as explaining how various practical tools and procedures can help to optimise these techniques and capture realistic stereo images — as might be employed for recording acoustic ensembles from duets to full orchestras, choirs, folk, jazz, ambient spaces, and more besides.

And for those immers‑o‑philes who might think stereo boring and old‑hat, it’s worth noting that the very concepts and techniques I’ll be discussing in relation to stereo recording can be expanded and enhanced for surround and immersive audio recording applications too!

...the very concepts and techniques I’ll be discussing in relation to stereo recording can be expanded and enhanced for surround and immersive audio recording applications too!

What Makes Stereo Stereo?

Before we move on, I think it’s helpful to consider, at least to a basic level, how our sense of hearing actually works, because the various stereo mic techniques are all designed to exploit one or more aspects of our hearing senses, and often they succeed or fail directly because of how they try to fool our senses.

Human hearing evolved, essentially, to warn us of impending danger located anywhere around us — the legendary sabre‑toothed tiger’s stealthy approach through the jungle, for example. Having made our brain aware of a potential danger, our hearing then provides sufficient extra information to enable the brain to turn the head to view that danger directly (the sense of sight generally has priority in fight‑or‑flight decision‑making). To that end, our ears and brain are amazingly well adapted at processing the minuscule differences between sounds arriving at each side of the head to evaluate the likely position of sound sources in 3D space around us. This is called binaural hearing (and is not to be confused with the stereo recording/replay format of the same name). Like all our senses, binaural hearing is not a perfect system and it has intrinsic flaws — many animals can do far better than we can, of course. Nevertheless, our sense of hearing is still pretty impressive, and it’s definitely worth looking after!

For humans, the accuracy of positioning a broadband sound source (ie. one with wide frequency content) varies across both the horizontal and vertical planes. But it’s generally agreed to be better than two‑degree accuracy for sources in the region directly in front of us, then reduces to about a 10‑degree error margin towards the sides, and is a little worse for sources behind us.

Our ears and brain rely on three distinct auditory cues to extract information about the direction of a sound source, as I’ll discuss below: inter‑aural time differences (ITDs), inter‑aural level differences (ILDs), and spectral artefacts (complex comb‑filtering effects caused by sound reflections from the torso and outer ears or pinnae). There is a priority order between these cues in determining source location, too, with ITDs being most relied upon, then ILDs, and spectral differences being used to add more detail and deconflict ambiguities — as well as coming to the rescue where true binaural hearing is impaired for some reason.

Inter‑aural Time Differences

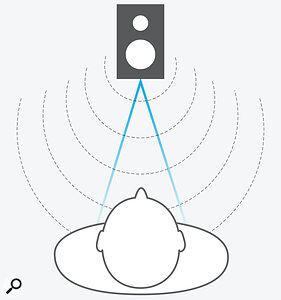

Inter‑aural time differences arise because sound travels relatively slowly through the air (roughly 340 metres per second). If you consider a sound source directly in front of a listener, the sound waves it emits will arrive at both ears simultaneously because the path lengths to both ears are identical.

However, if that source moves off to one side, then its sound waves will reach the closer ear slightly earlier than the distant ear (because the path lengths are now different). By comparing the timing of nerve impulses from each ear, the brain can work out whether the sound source is located towards the left side or the right, based simply on which ear detects it first.

Moreover, by examining that timing difference more critically, the brain can calculate the angle of sound incidence with surprising accuracy. The diameter of an adult’s head is typically between 19 and 22 centimetres, which means, for a sound source at 90 degrees, the maximum time difference between sounds arriving at each ear is about 0.67 milliseconds. Lab tests suggest that the brain can detect differences in arrival times down to around 0.01ms (10 microseconds) — this is what gives us an angular resolution of about two degrees.

Sound waves emitted from a sound source directly in front of the listener arrive at both ears at the same time because the path lengths are identical.This ITD calculation is thought to be derived mainly from transients within the sound signal, which is probably why it’s often quite difficult to locate sound sources without transients — pure sine wave tones, for example. For periodic signals like these, the brain has to use phase differences between the two signals instead. However, the maximum ITD of 0.67ms corresponds to a frequency of 1.5kHz, where the complete wavelength is roughly the same as the diameter of the average head. So, signals with fundamental frequencies higher than this will arrive at the distant ear with a phase difference greater than 360 degrees, and this inevitably creates confusion and ambiguous locational information because a phase difference of 405 degrees looks the same to the brain as one of 45 degrees (45 + 360 = 405), Thus, for periodic signals the ITD method is only reliable at frequencies well below 1.5kHz.

Sound waves emitted from a sound source directly in front of the listener arrive at both ears at the same time because the path lengths are identical.This ITD calculation is thought to be derived mainly from transients within the sound signal, which is probably why it’s often quite difficult to locate sound sources without transients — pure sine wave tones, for example. For periodic signals like these, the brain has to use phase differences between the two signals instead. However, the maximum ITD of 0.67ms corresponds to a frequency of 1.5kHz, where the complete wavelength is roughly the same as the diameter of the average head. So, signals with fundamental frequencies higher than this will arrive at the distant ear with a phase difference greater than 360 degrees, and this inevitably creates confusion and ambiguous locational information because a phase difference of 405 degrees looks the same to the brain as one of 45 degrees (45 + 360 = 405), Thus, for periodic signals the ITD method is only reliable at frequencies well below 1.5kHz.

Inter‑aural Level Differences

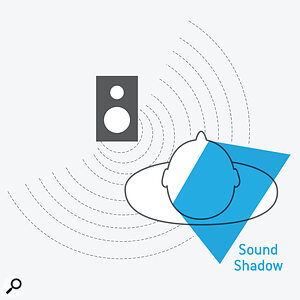

Sound waves emitted from a sound source to one side will arrive at the closer ear before the more distant ear, because the path lengths are different.The second methodology, Inter‑aural Level Differences (ILDs), is caused mainly by us having an acoustic ‘baffle’ between the ears — otherwise known as a head! At higher frequencies (above about 1.5kHz, where the wavelength approaches the diameter of the average head), this causes a ‘sound shadowing’ effect for the distant ear.

Sound waves emitted from a sound source to one side will arrive at the closer ear before the more distant ear, because the path lengths are different.The second methodology, Inter‑aural Level Differences (ILDs), is caused mainly by us having an acoustic ‘baffle’ between the ears — otherwise known as a head! At higher frequencies (above about 1.5kHz, where the wavelength approaches the diameter of the average head), this causes a ‘sound shadowing’ effect for the distant ear.

Consider a sound source directly in front of a listener, again: the sound level of high frequencies reaching both ears will be the same, because there’s nothing in the way between the source and ears to affect the sound level. If that source moves off to one side again, while remaining at the same distance from the closest ear, the level at that closer ear will remain the same. However, the level at the distant ear will be reduced slightly because the sound waves diffract around the head, creating a ‘sound shadow’. The actual amount of signal‑level reduction is a function of both the angle of incidence and the source frequency; the attenuation due to diffraction increases as the frequency rises and the wavelength decreases.

As high‑frequency sound diffracts around the head a sound shadow is created, reducing the level reaching the distant ear.

As high‑frequency sound diffracts around the head a sound shadow is created, reducing the level reaching the distant ear.

These two primary sound localisation systems, ITDs and ILDs, function largely independently of each other. In experiments using headphones, though, it’s possible to use a delay at one ear, creating a contradicting ITD, to overcome the perceived source direction generated by an ILD. That’s an effect that can’t happen in real life, of course, but it does illustrate just how easily the brain can be fooled! Importantly, turning the head towards a sound source will always reduce both the ITD and the ILD (turning away increases both), which is another important aid used by the brain to deconflict ambiguities and bring the sound source into sight. This is why people often unconsciously tilt or turn their heads when listening to something intently: it’s an automatic response.

Spectral Distortions

The third location‑detection process, spectral cues, is about decoding complex spectral distortions that are created by interference patterns occurring between the directly arriving sound waves and reflections off the shoulders and from the curves of the pinna. Essentially, these are unique comb‑filtering response dips, and these high‑frequency interference patterns vary with the angle of sound incidence (both horizontally and vertically). They are absolutely unique to each individual, too, because they are wholly dependent on the exact shape of the outer ears and other aspects of the person’s physique. In early life, the brain learns to correlate these unique spectral distortions with known sound‑source locations, and the individual gradually develops the ability to locate sound sources just through recognising specific spectral distortion patterns.

Spectral cues are entirely monaural — the sound source location can be calculated from the spectral distortions to sound waves detected using a single ear!

Interestingly, whereas ITDs and ILDs are both binaural hearing processes (meaning the brain makes use of both ears to evaluate the sound direction), spectral cues are entirely monaural — the sound source location can be calculated from the spectral distortions to sound waves detected using a single ear! More importantly, spectral cues are particularly important for resolving front/back confusions and source locations in the vertical plane, which ITDs and ILDs can’t differentiate at all.

Monaural Location

This mechanism explains how deafness in one ear doesn’t destroy the ability to locate sound sources. If you’d like to test it, try lying in bed with your eyes shut and one ear buried in a pillow (thus removing the option for binaural hearing) as a partner or child enters the room and moves around the bed. You’ll find you can estimate their position in the room with surprising precision, even without binaural hearing!

And, if you think about it, one reason headphone listening can sound artificial, with sound sources perceived as being inside the head rather than in the space around it, is that these spectral cues are inherently absent; the sound is essentially injected straight into the ear canal without the benefit of reflections from the pinnae and shoulders. This missing information confuses the brain to decide sounds must be ‘inside the head’. Even with true ‘binaural recordings’ — I’ll be discussing those in a later article — the perceived ‘outside the head’ sound locations are often variable for different listeners.

These ‘problems’ can be addressed very effectively using crossfeed matrix processing, which simulates the natural ‘crosstalk’ of sounds arriving at both ears in the real world, and personalised Head‑Related Transfer Functions, or HRTFs. HRTFs are a set of spectral (frequency) modifications that are applied to the binaural signal, to simulate different intended sound‑source locations. But, while generic HRTFs can certainly be helpful, if we’re to perceive accurate and stable image locations we require HRTFs that are designed specifically for each individual — that’s because we each have uniquely shaped pinnae and different physiques. Thankfully, technology is starting to make that a lot easier to achieve, with quite good results coming from analysing photographs of an individual’s ears, for example!

...while generic HRTFs can certainly be helpful, if we’re to perceive accurate and stable image locations we require HRTFs that are designed specifically for each individual...

Auditory Cues, Mics & Loudspeakers

So, our ears and brain derive the location of a point‑source sound through ITDs, ILDs and spectral cues, and we try to recreate that information by using two loudspeakers spaced apart, preferably at ±60 degree angles to our listening position. What could possibly go wrong?

Amazingly, this peculiar scheme works well, fooling our ears/brain into creating ‘phantom sound sources’ that appear to be positioned somewhere in the space between the speakers. Technically, it recreates the sound wavefronts required to work very well at low frequencies (below about 700Hz), where level differences between the two speakers create accurate ITDs at the ears (that’s right, time differences! More on that in a future article...). At higher frequencies, the system doesn’t work quite so well and, in effect, creates spatial aliases that smear the soundstage and reduce imaging accuracy.

For stereo recording, the microphones are tasked with capturing ILD and/or ITD information in lieu of our own ears, and different stereo mic techniques achieve that in different ways. I’ll be looking at these, and delving into the mysterious workings of stereo loudspeakers, in Part 2 of this series next month.