Isabel Garvey is Managing Director of Abbey Road Studios.

Isabel Garvey is Managing Director of Abbey Road Studios.

Are cloud-based mastering services a threat to traditional mastering engineers, or just a cheap alternative for producers who can’t afford the real thing? It depends who you ask...

Why would the world’s most famous studio promote something that threatens to undermine part of its core business? It’s a question that Isabel Garvey, Managing Director of Abbey Road Studios, is getting used to answering. “Some people seem surprised that a facility with lots of traditional mastering engineers, technology and expertise would launch an incubator programme which welcomes technology businesses that potentially disrupt the studio model. ‘Why would you do that?’ they ask me all the time. The short answer is: because it is fascinating, and the possibilities are really very exciting. The last thing we would want is to be fighting an inevitable change. We want to be a part of this revolution, not have the revolution happen to us!”

The disruptive technology in question here is automated mastering. Online, cloud-based services are springing up which purport to take raw mixes and deliver polished masters without any direct human involvement. Perhaps the best-known of these is LANDR, which has been making waves for a year or two now, while Abbey Road have gone into partnership with rival service CloudBounce. Does the rise of automated mastering threaten the jobs of established mastering engineers, including the distinguished team at Abbey Road itself? Which aspects of the mastering process, if any, can successfully be handed over to automated processors?

Mastering For The Masses

To try to answer these and other questions, I spoke to Isabel and to several mastering engineers at Abbey Road and other studios, and also to Anssi Uimonen of CloudBounce, and Justin Evans, co-founder of LANDR. All of them agree that the usefulness of cloud-based mastering tools — and their potential to displace human beings — depends to a great extent on your expectations of the mastering process. “Of course, there are many things a mastering engineer will do that we will never be able to do,” admits Justin Evans. “The critical insights a mastering engineer can give in a conversation with a musician... that is something that even the best AI in the world wouldn’t try.”

Abbey Road engineer Sean Magee shares this perspective. “There’s no way these services can ever be true competition. Someone who can afford to pay to have a human do their mastering, whether it’s online or by coming to Abbey Road in person, will pay to do that, because there are things we do that they can’t do. If you’re taking your music to that kind of level, the chances are you’re going to want a better service than these automatic tools can offer you.”

Sean Magee has been an Abbey Road mastering engineer for almost 20 years, and won a Grammy for his work on the Beatles remasters in 2009.

Sean Magee has been an Abbey Road mastering engineer for almost 20 years, and won a Grammy for his work on the Beatles remasters in 2009.

The One & The Many

So, what are the things that human mastering engineers can do that these automated services can’t? The mastering engineers I spoke to all argue that cloud-based services currently focus on glossing the sound of individual tracks, without reference to musical context. Legendary mastering engineer Vlado Meller puts it succinctly: “It’s not about how loud or quiet the particular song will be, but how the whole album of 10 or 12 songs will sound as one cohesive package, despite the songs being recorded in six different studios by six different engineers. The final outcome has to be one cohesive-sounding album. There is no algorithm capable of creating that. Perhaps 10-15 years from now there will be an algorithm that mimics 10 million different ears and sensitivity situations, but for now, professional human touch in music production is vital, human listening is vital, and human decision in sculpting sound is more than vital.”

Vlado Meller is one of the world’s most in-demand mastering engineers, with a credit list that runs from Celine Dion to Metallica.

Vlado Meller is one of the world’s most in-demand mastering engineers, with a credit list that runs from Celine Dion to Metallica.

“These services are limited to individual tracks,” agrees Sean Magee. “You can’t throw a collection of tracks recorded in different places, or with different producers, at them and expect to get an album of tracks with a unified sound. Or live tracks recorded at lots of different venues, and get a coherent-sounding live album. Because how does an algorithm decide what that coherent sound is going to be? That’s a creative decision. Music has no rules, and how can an algorithm, a collection of rules, be applied to music? There’s not one way to ‘EQ a voice’. There’s not one way to ‘EQ bass’. You can do that on three days in succession on this job and do it completely differently each time. What’s more, all three ways will be ‘right’ for those particular projects.”

His Abbey Road colleague Geoff Pesche is of the same opinion: “Pretty much anything with a musical element to it is going to be hard for software to recreate. When you make an album master, you know, sometimes even the pauses between the tracks are actually musical. That sounds like I’m being pretentious — even my silences are musical! — but you know what I mean. I mean when a track ends, and the next one starts after a pause of a certain length, so the new track seems to start as a response to the end of the previous track. You can only do that by analysing the two songs next to each other with a musician’s ear, a sense of rhythm and feel. A machine, or a software algorithm, might be able to learn how to do that, but would it ever be able to come up with the idea of putting those two tracks together like that in the first place? Or to come up with the idea of crossfading two tracks together? Those are musical ideas, creative decisions. Even something as simple as deciding how to apply EQ can fall into that category. We can do some pretty heavy sonic resculpting of tracks in mastering if we want to — but only the artist can tell us if we should or shouldn’t.”

Over the course of a long career, Geoff Pesche has worked at many of London’s biggest mastering studios. He joined Abbey Road in 2006.

Over the course of a long career, Geoff Pesche has worked at many of London’s biggest mastering studios. He joined Abbey Road in 2006.

The YouTube Generation

Justin Evans admits that LANDR focuses on individual tracks, but explains that this is principally a reflection of the way music is consumed today. “We live in, and love, the world of SoundCloud and streaming services. Today, most songs are listened to alone, or as part of a streaming playlist instead of a coherent album. We think this raises many interesting questions about what mastering means. In the ’40s, mastering was part of the job of a transferring engineer. Then vinyl and radio changed that. Now we are living in a streaming world. What should mastering be now? That question shaped our original product vision.”

He goes on to offer a warning to any human mastering engineer who believes that algorithms will never meet the challenge of assembling satisfying albums: “With that said, we still are super-interested in albums. I’m in my ’40s. I’m a ‘lean-in’ listener that still listen to records. Using algorithms to make a coherent album is also a really fun problem to solve. We do have an album mastering prototype that we use in our professional services division, where we do albums for major labels. We run them through this prototype, and then our human engineers tweak the results. The algorithm learns from what they are doing and gets better. After a year of doing this, the results are starting to get quite interesting. We’re excited to release it when it’s ready, but it’s going to take a lot of data to get it right!” Anssi Uimonen is co-founder and CEO of CloudBounce.

Anssi Uimonen is co-founder and CEO of CloudBounce.

Anssi Uimonen likewise points out that what’s impossible for algorithms today might be feasible tomorrow: “Automated mastering is still in its infancy, and we believe that its capabilities and features will evolve towards a high-price-tag human mastering session — maybe even further in some areas. The decision-making processes and referencing behind the algorithm will be taken much further to provide better mastering results, definitely. It’s hard to predict exactly when it will happen, but we think the technology might suprise the audience once its full potential is reached.”

Talk To Me

Another key element most people see as missing from cloud-based services, at least in their current form, is communication. “We bring proper, artistic, human consultation to the process,” says Sean Magee. “When I master tracks for somebody, or an album, I’ll expect to spend a decent period of time just talking to the artist, finding out what sound they’re looking for. I find out what their expectations are, I find out what they think of their own work, which bits they’re happy with, and which bits they’re not.”

“Everyone in the industry knows that the mastering engineer is a crucial second or third opinion in a recording project,” agrees Vlado Meller. “The same master given to three different mastering engineers will produce three distinct-sounding recordings, which proves that every mastering engineer has a different way of interpreting and processing the sound.”

Geoff Pesche sums it up: “You can’t have an interactive relationship with an algorithm.”

Once again, though, the people behind the cloud-based mastering services warn us against saying ‘never’. CloudBounce’s Anssi Uimonen responds: “Communication is clearly one of the key benefits of a human mastering session. A real relationship forming through discussion and getting professional feedback is of course valuable in terms of mastering results. However, we think that, over time, more and more features can be brought to algorithm-based mastering to remedy the issues currently only humans can fix.”

Genre Genies?

The human mastering engineers I talked to were also sceptical about the ability of automated services to ‘understand’ genre-specific trends, and to respond to unconventional artistic visions. Abbey Road’s Christian Wright gives an interesting real-world example. “I uploaded a deliberately bass-heavy track to some of these automatic services to see what came out. It came back with all the bass nicely tamed and reined right back, but it didn’t fit the intentions of the original artist. You need to know what’s musically right for the genre you’re working in, and for mastering machines that are supposed to be able to cope with any music you can throw at them, that means they’ve got to be able to reliably recognise styles of music, just from a sound file. That’s much, much harder than it might sound, and I don’t think any of these services are really there yet.

Christian Wright joined the Abbey Road staff at the age of 19 and has worked his way up to his current position as one of their most sought-after mastering engineers.

Christian Wright joined the Abbey Road staff at the age of 19 and has worked his way up to his current position as one of their most sought-after mastering engineers.

“A machine, or a piece of software, is always going to be behind the curve. An algorithm is just a set of rules for how to do something. But the ‘rules’ in music are always changing: as fashion changes, as new scenes spring up, new kinds of music are created, with new production techniques and popular sounds — and that’s always been particularly true here in the UK, where there’s a really fast turnover of styles and fashions at any one time — almost too fast, you might say. You can only react to those developments with an algorithm in retrospect, and program your software to do something because it sounds like something that’s already gone before. But the best new music will often break the rules set up by what’s come before. So what’s an algorithm going to do to really groundbreaking new music? It can’t help but treat it like something that’s gone before, because that’s all it will ever be programmed to do. A couple of months later, the programmers might come up with an algorithm that can master that style of music the way the original artist envisaged it should sound. But by then, there’ll probably be a new scene, and a new sound. There’s always going to be a lag.

“Now, obviously, human mastering engineers have to move with the times as well to stay abreast of new styles. But the thing is: we do. We all love music here. We’re all out at gigs every week, or a couple of times a week, listening and absorbing, making music ourselves, even. And the human ear can assimilate, understand, interpret and react to a new style of music, or a new kind of production, far quicker than any machine can — especially if you have the opportunity to talk the music through with the artists who are creating this stuff when you work with them, like we do.”

Sean Magee agrees. “You wouldn’t apply the same kind of mastering to Iron Maiden as you would to Sepulchre, but many people would consider them both ‘rock’. For some people, ‘rock’ might encapsulate any guitar-based band music from 1955 to the present, but it’s a fairly obvious point that there’s not one sound that works for any music recorded in that genre between now and then. There are so many genre-based mistakes that could be made by a machine. If you throw some drum & bass or dub reggae at a mastering algorithm, the chances are it will consider the bass frequencies to be far too high and tone them down, or even take them out. But that would be a massive creative error in those genres.” LANDR co-founder Justin Evans.

LANDR co-founder Justin Evans.

In Translation

Justin Evans, however, says that not only does LANDR already offer genre-specific mastering, but that it’s getting better all the time. “LANDR’s genre-recognition engine treats every single one of those tracks differently. We have a patented machine-learning approach to this question that is based on over seven years of research. Both our data science team and our human engineers are constantly working on refining the approach. This is why we release updated engines regularly — for example, we launched a DJ-specific engine in April and a streaming engine with SoundCloud in May — and that is a key part of how LANDR keeps getting better. The more data we have, the more sophisticated our understanding of genre is. LANDR today is a significant improvement over when we launched. It’s learning all the time and it’s very exciting to think about what it will sound like at this time next year.”

Anssi Uimonen of CloudBounce is a little more circumspect, but it’s clear that he too believes the goal of having mastering automatically tailored for specific genres is within reach: “As stated, this technology is still very young and can be developed much further. We truly believe that the automated mastering technology will be able to answer to that challenge in the coming years and cater to genre specific needs on a different level not seen yet.”

However, there are limits, at least for now. As Christian Wright found, the overriding goal of automated services from a sonic point of view is the ability to deliver a track that sounds acceptable on as wide a variety of playback devices as possible. Other priorities are not always catered for, as Justin Evans admits. “You can of course target certain masters for certain environments, but a big part of mastering is translation. A good master should translate across a variety of playback systems. So the most important goal for LANDR is to create a master that will sound good anywhere. That said, there are definitely additional services we are considering offering to our users in the future to address this even more deeply.”

Anssie Uimonen likewise describes the primary function of CloudBounce in terms of ‘translation’: “While the mastering process can’t cure mixing issues, it can enhance the overall sound quality of a balanced mix to a commercially competitive level so that it can be safely published and therefore make it sound at its best on different platforms.”

Fresh Territory

In conclusion, it’s fair to say that although automated services are improving all the time, they are still some way away from fulfilling all the roles that a human mastering engineer can. But it would be a mistake to write them off as merely second-rate, cut-price alternatives to the real thing. As things stand, LANDR and CloudBounce are not competing with human mastering engineers but operating in an entirely new market, opened up by wider changes in the way music is created. And if Isabel Garvey and her team seem relaxed about the impact on their business, it’s because these services mainly target producers who aren’t otherwise using professional mastering engineers at all. “The technology available to the music-maker today is continuing to change and enhance the creative process,” she says. “There is more opportunity to tweak as you go along; to add to your work continually and collaborate rather than just follow the old ‘record, mix, master, finish’ processes. These shifts are affecting mastering in a number of ways, and are creating opportunities for both automated and human-controlled solutions.

Not available in the cloud: a classic EMI mastering console at Abbey Road.Photo: Hannes Bieger

Not available in the cloud: a classic EMI mastering console at Abbey Road.Photo: Hannes Bieger

“For example, we are seeing some people using these new automated online mastering services as an affordable mastering solution for their demos, while they are producing a track, to give them an idea of how their track might sound once it’s been given a final master by an engineer. That can inspire you further, and actually feed back into the creative process. Some users are using the mastering services as an effect in their own right, and then taking the processed tracks back into their mixes! As the guys from CloudBounce love to say, their technology isn’t replacing traditional stages and methods of the music-creation process; instead, they’re enhancing and adding to it.”

Justin Evans goes even further, suggesting that automated mastering is not only a tool in its own right, but a valuable learning aid for today’s producers. “Because LANDR is so affordable, our users are using LANDR to learn how to ‘fix it in the mix’. We consistently see people using LANDR many times over and over again on a single track. When we’ve spoken to the users who do this, they tell us that they use LANDR as a tool to audition their mix, hear what’s wrong with it, go back and retry it and iterate from there. People love it, because it’s like having a huge budget where you can go back and forth with a mastering engineer as many times as you need to get it exactly where you want. It also really gives control to the artist over their sound, at a stage where they often feel like they lose it and have to pass it over to an expert. Who doesn’t love that kind of empowerment?”

“Although we are bringing a new solution to the mastering arena, we are not necessarily rivals,” insists Anssi Uimonen. “We serve a different audience and purpose by giving a fast but high-quality option for the mass market, serving their specific needs. Currently we see ourselves being complementary to the traditional mastering services, and appreciate its strengths as a well-rounded professional experience. However, an average bedroom producer doesn’t necessarily need that level of detail and cost to publish their tracks. We think that a large majority of the YouTube generation still benefits greatly from an automated service, offering a great product-market fit. The budget-minded creative public wants quality results fast, and that’s exactly where we excel.”

And, as Abbey Road’s Christian Wright explains, it’s not as though there is a fixed supply of music that has to be divided up between human mastering engineers and their cloud-based counterparts. Quite possibly, there’s enough work for all. “There’s so much music being made around the planet now, not just in bedrooms and rehearsal rooms, but on trains, in colleges and schools anywhere there’s a laptop, really. Even if we wanted to, there’s no way we could master all of it at Abbey Road, even using our online services. The automatic services allow some of that to be finished to a standard that its creators are satisfied with, and made available around the world. That’s fine by us.”

LANDR & CloudBounce In Use

So, are these newfangled cloud-based mastering services any good? And what are they like to use? To answer these questions, I obtained some credits from both services and ran some tracks of my own through them. Out of curiousity, I also invited the Abbey Road mastering engineers who took part in this article to tackle one of the tracks, in an informal man-versus-machine master-off.

LANDR and CloudBounce both reflect achingly contemporary trends in web design.

LANDR and CloudBounce both reflect achingly contemporary trends in web design.

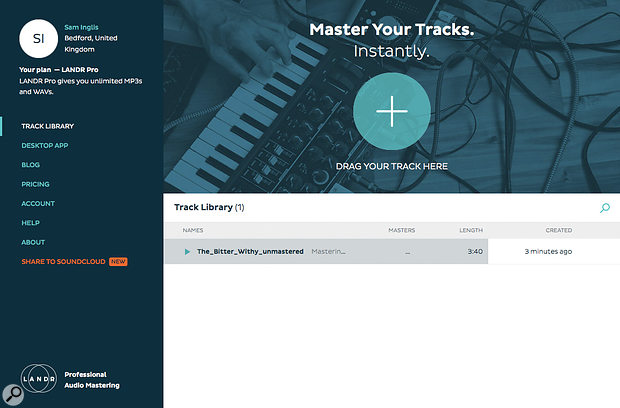

From the user-experience point of view, both LANDR and CloudBounce are utterly of the moment, with much thought given to simplicity and streamlining, and endless pop-up opportunities to chat with team members. Both can be used as stand-alone Web-based services, but a level of DAW integration is also available, as is a desktop app in the case of LANDR. In all cases, there’s no denying the utter immediacy of the process. Assuming you’re using the Web-based version, you simply drag and drop your unmastered audio file from the Mac OS Finder or Windows Explorer onto a big circular target. Once it’s uploaded, there’s a brief analysis process, whereupon your newly mastered track is streamed back at you, with a button that lets you A/B it against the unmastered original (without any form of gain matching, natch).

Both sites offer a deliberately limited palette of options for tailoring the mastering to your requirements. In the case of LANDR, all you get is a choice of three ‘intensity’ levels; more intensity seems to equate, roughly speaking, to louder and brighter. CloudBounce, meanwhile, lets you select Louder, Quieter, Warmer and More Bass as binary options; a fifth choice lets you send dedicated feedback on your master, but unfortunately this isn’t interpreted as instructions by the mastering engine — it just goes to the developers.

One thing no human mastering engineer could possibly hope to match is the turnaround times offered by these sites, both of which operate signficantly faster than in real time. Slightly to my surprise, I found that both services defaulted to relatively subtle treatment on my first test track. At standard Intensity and loudness settings, both sites returned a master that was quieter than my fairly conservative home-brew effort; each, in its own way, was a shade brighter than the unmastered track, but neither changed the tonality a great deal. I’d have been perfectly happy to use either version, but in all honesty, I didn’t feel they represented a huge improvement over the results I’d got by putting IK’s Stealth Limiter over the mix bus. Pushing the Intensity or loudness in order to squeeze maximum loudness out of the track brought an uncomfortably gritty edge to things.

By contrast, the version that Geoff Pesche of Abbey Road mastered was noticeably louder and much brighter than anything I could get out of LANDR or CloudBounce. In fact, Geoff commented that he thought the original mix was a bit lacking in top end. So are LANDR and CloudBounce not capable of identifying and compensating for mix problems of this sort, or was this just a question of personal preference? To find out, I tried loading up a much earlier rough mix of the same track, which definitely did have some issues of frequency balance, most obviously a hole in the mid-range. Both services altered the tonality a little more this time around, but if anything, they actually made the hole worse, adding brightness in the upper mid-range rather than filling out the 1kHz region.

At present, then, it seems that the cloud services can’t offer the same ‘safety net’ as conventional mastering; nor can they give you the same sort of useful mix feedback that I got from Geoff.

If you can bear to listen to multiple masters of a traditional ballad about the incident that ended Jesus’s football career, arranged in a disco style, head to this month’s media page at sosm.ag/sep16media to compare them.

Zen & The Art Of Audio Mastering

Human mastering engineers might not want to be put out of a job by their automated rivals, but they are usually only too happy to find that their services are not needed. As Abbey Road’s Sean Magee puts it, “The art of a good mastering engineer is knowing when to do very little. In all seriousness, that’s an important part of my job. If they like nearly everything they’ve mixed, and I don’t notice anything glaring that the artist has missed when I listen through the material, then I do my best to simply assemble it, and not to do very much at all, in terms of work on the sound and audible EQ’ing. And you could say that’s a real test of these automatic mastering services. Do they know when to leave well alone? The difference between artificial intelligence and intelligence is still pretty huge in this field.”

LANDR co-founder Justin Evans agrees that his service never “leaves well alone”, even when presented with a track that’s already been mastered. This, however, is not down to artificial intelligence or lack thereof, but because his clients expect LANDR to do something to whatever they upload. “Why we decided to always do at least something, instead of saying ‘Hey, great, your track is ready to go!’ is because of user feedback we got from our most engaged users. Some of our pro mixers are guys that mix very hot. They use LANDR, especially the low setting, for a transparent and light touch that smoothes some of the edges off their mix. We sent them out the version of the LANDR engine that wouldn’t make any changes to files it understood as ‘already mastered’, and we found that they kicked back pretty hard, since it took away the main use they had for LANDR. So our compromise has been to always do a little, no matter what.

“If you put a mix into LANDR that’s already pretty great, our algorithm is always going to identify that it needs to do less than if you put in something that needs a lot of work. That said, because we aren’t talking to the musician, we have to use machine intelligence to understand what it is they are looking for, the choice is between erring on the side of too much or too little. This is something we’ve gone back and forth on many times.”

CloudBounce takes a different approach, as Anssi Uimonen explains. “Applying processing for the sake of making an impact is not always what’s needed. With the help of a free mastering preview and additional mastering options you can fine-tune towards more specific sound if that’s what the track needs. The basic mastering process is tuned to make more conservative adjustments and you can fine-tune to taste with preset options and add the level of processing. The mastering algorithm is able to detect if the audio track is already mixed or mastered with very little or no headroom, and makes decisions based on the general signal level, peaks and audio waveform, among other things. In this case the applied processing is left to mimimum or none at all.”

Computers: Not Very Technical?

Cutting a vinyl master is a specialised skill which is currently off the table for automated services.

Cutting a vinyl master is a specialised skill which is currently off the table for automated services.

Perhaps surprisingly, one key limitation of existing cloud-based mastering systems is their inability to carry out some of the more technical functions that are routine for their human counterparts. Abbey Road mastering engineer Sean Magee: “Important aspects of the mastering process, like adding PQ codes, gaps, fades, crossfades: they can’t be done automatically. Even taking out clicks, which we do all the time, is a hit-or-miss process. How does some software decide what is unwanted noise and what’s electronic percussion, or deliberately added vinyl crackle for ambience? When we listen, we know what’s music and what isn’t, what’s part of the intention and what’s a mistake, and we know what to remove or tone down.

“All software-based mastering can do for now is take care of the part that is actually optional. It’ll take your track and make it louder and brighter, but it can’t produce anything that will go to a factory as a master. And it whilst it might produce a result that’s usable online, it certainly can’t cut a vinyl record, or even necessarily create a master that’s ready to cut vinyl from.”

Audio Examples

Download | 170 MB