Martin Fry with gold lamé suit and magic sax. Photo: Sheila Rock/REX/Shutterstock

Martin Fry with gold lamé suit and magic sax. Photo: Sheila Rock/REX/Shutterstock

1982’s ‘The Look Of Love’ paired an ambitious band with an ambitious producer, and the result was a perfect piece of pop music.

Few tracks evoke the spirit of 1982 as vividly as ABC’s ‘The Look Of Love’. In an era of post-punk synth-poppers, the Sheffield group — guided by high-concept producer Trevor Horn — managed to create a widescreen sound that blended Nile Rodgers’ and Bernard Edwards’ immaculate productions for Chic with Nelson Riddle’s dramatic orchestrations for Frank Sinatra.

“It was like Chic with Bob Dylan over it,” Trevor Horn says today of ‘The Look Of Love’. “That was kind of how they had it in their heads. The guys in ABC used to go to a club up in Sheffield, and they wanted to make a record that they could play in the club. If you think about it, in the ‘70s, disco production was the thing that pushed everything forward. I mean, rock production was pretty cool too... But the way that people made dance records was so different. Y’know, they would separate all the drums. The drums would have to be very dry and thick and all that kind of thing.”

For Horn, ABC’s musical vision completely mirrored his own at the time, namely to create precise, imaginative, state-of-the-art productions. “I was trying to make something better than you would normally make,” he laughs. “I suppose I was trying to make records to compete with America.”

When Trevor Horn and ABC first met in 1981, in a rehearsal room in Queensway, West London, following the band’s debut hit with the Steve Brown-produced ‘Tears Are Not Enough’, it was clear that they shared certain interests and ambitions.

“I was one of about 15 producers they saw,” Horn remembers. “My late wife [Jill Sinclair], who was my manager at the time, had said to me, ‘I’ve found a band who’re perfect for you... this group ABC. They’re intelligent, the songwriting’s really good, but they need something more.’

“So I met them and [laughs] I was probably pretty full of myself. They were definitely! We got on really well. They were into interesting old magazines and I was also into magazines. So they pulled out a couple and I can’t remember what their magazines were, but I had a couple of American wrestling magazines. At the time — and y’know we didn’t have the Internet back then — to me magazines were like an insight into different cultures. I think we were kind of kindred spirits in a certain way.

“I just remember they said to me, ‘If you get to produce us, you’ll be the most fashionable producer in the world, because we’re the most fashionable band in the world...’”

Irritable Drummer Syndrome

ABC evolved from a Sheffield synth group called Vice Versa and, by the time Trevor Horn met them, had settled on a line-up comprising singer Martin Fry, guitarist Mark White, saxophonist Stephen Singleton, drummer David Palmer and bassist Mark Lickley.

Horn, meanwhile, had been building a renown as both a musician and producer — as the face of the Buggles and their 1979 number-one single ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’; and the singer in a reconfigured Yes, the production of whose 1980 album Drama he was heavily involved in. Having been a session musician in the late ’70s, he had worked with disco singer Tina Charles and her producer Biddu, with the latter’s recordings firing Horn’s imagination when it came to his own studio work.

“Back then, there was no tuition in these things,” he points out. “To become a record producer was very, very difficult. In order to produce a record, you had to go in a studio and a studio cost a lot of money. When you first got into a studio, you didn’t have a clue what you were doing. So it was tricky. I was doing a lot of work for publishers, demo songs and things like that. And I suppose the thing I learned from Biddu I only learnt because I was living with Tina Charles.

“One night she came home and she had the backing track for [1976 number one] ‘I Love To Love’. I’d never heard a backing track before done by a hit producer and it was fascinating because it was kind of brilliant. It was dead simple, there wasn’t a spare thing on it. I must have listened to that about 30 times. It made me realise that I’d gotta stop fucking about — I’ve got to make the drummer play the right pattern. Because, y’know, back then drummers would get well shirty if you tried to make them play four on the floor.”

In 1977, to get around the problem of working with irritable drummers, Horn went into a studio to create a multi-purpose rhythm track that he could adapt for various recordings. “Y’know, I made myself a ‘drum machine’,” he says, “but I made it on 24 track tape. I recorded everything separately, just a very basic beat — eighths on the hi-hat, off beat on the snare, four on the floor, done to a metronome with a very grumbly drummer who I had to pay over the odds to do it. And then you could make a drum track by speeding it up or slowing it down to your tempo, and then editing it, and printing it off to half-inch tape and then copying it back onto a two-inch tape. I used that for making demos and it was a good drum sound.”

By ’82, Horn had also had the experience, through making Drama with Yes, of working with 48 track. “I’d sort of ended up producing that along with the other guys [and Eddie Offord]. If you mixed with two machines, it was incredibly slow. So I had a bit of an idea of what I was doing technically.”

Tracing

All of this was to serve Trevor Horn very well when he produced a series of hits for pop duo Dollar before moving onto ABC. Their first record together was the 1982 single ‘Poison Arrow’. “We routined the song in a rehearsal room,” he recalls. “I remember going through it and I said, ‘You need something like a middle eight.’ And Martin came up with this bit in the middle where he says, ‘I thought you loved me, but it seems you don’t care’, and [guesting on the subsequent record, Karen Clayton] says, ‘I care enough to know I can never love you.’ I was quite impressed with that. It sounded to me like the kind of idea I used to have that people didn’t want to do. I thought at the time, ‘This is a good sign.’”

RAK Studios in London, where Trevor Horn and ABC first recorded together.

RAK Studios in London, where Trevor Horn and ABC first recorded together.

Entering RAK Studios near London’s Regent’s Park, ABC ran through ‘Poison Arrow’ as a live band take. “I said to them, ‘Is this what you want?’” Horn remembers. “‘Is this kind of good enough? Is this what you saw? ‘Cause we could get it better than this.’ And they said, ‘How do we get it better?’ I said, ‘Well what we’ll do is I’ll program into my 808 drum machine exactly what you’ve played on the drums, Dave. And I’ll sequence the bass [using a Roland sequencer] on this Minimoog. And then it’ll be like tracing. You play the drums on top of it and we try and get you to play exactly in time with those drums.’ So that’s what I did.

“It took about eight hours to program and then I had to leave, ‘cause it was a Friday. I left the engineer recording the drums and then we started work the following week. And the drums sounded great — he’d really nailed it — and then the bass player played along with the bass.”

ABC were clearly taken with this method since, when it came time to record follow-up ‘The Look Of Love’, drummer David Palmer had bought a LinnDrum machine and programmed the beat for the track before the band went into the studio. “He’d got the idea,” says Horn. “You’re talking about 1982 and drummers could play with clicks, but playing exactly in time with another drum track, or as close as you could manage, was a lot harder. Dave was really good and he just got better and better. He was way better than he ought to have been, if you know what I mean, coming from a little band from Sheffield who’d been playing synthesizers that they’d carried around in carrier bags.

“With ‘The Look Of Love’, they’d done most of the work when I got to it — they had the Minimoog bass part, they had most of the song. The part that I got involved in was making more of a journey out of it.”

Crack Squad

For his work with ABC, Trevor Horn assembled a production team around him who would add much to the band’s sound. First of all, he employed keyboard player/string arranger Anne Dudley, whose soaring orchestrations for the group first featured on ‘The Look Of Love’.

“I’d met her doing a gig playing with this band down in Wimbledon,” Horn remembers. “Anne came in to do a dep one night and she was fucking blinding. She didn’t just read the music, she played loudly and confidently and she brought the whole thing to life. I said to her, ‘I’m a producer and one day you’re gonna play keyboards on my stuff.’ Of course she probably thought I was a chancer.

“She came and played on the last two Dollar records and she was brilliant, particularly on ‘Give Me Back My Heart’. So when I started on ABC I knew I was gonna bring Anne in and all the counter melodies that she put on ‘Poison Arrow’ were terrific. When it came to ‘The Look Of Love’, I told them I thought we should use a string section and they were up for it.”

Trevor Horn at Sarm Studios’ SSL 4000E.

Trevor Horn at Sarm Studios’ SSL 4000E.

Another key member of the team was engineer Gary Langan. “Gary was brilliant,” says Horn. “He’d tell me off and say, [sarcastically] ‘Are there enough overdubs on this track? How the fuck am I gonna mix this?’ He’d do things like put an echo on something and I’d go, ‘My God! Can we get away with that?’ I mean, he and I, we got crazier and crazier. The vinyl cutting engineer was always moaning at us.”

The final addition to the production crew was JJ Jeczalik, brought in to program the Fairlight CMI sampler that Horn had recently purchased for an at-the-time eye-watering £18,000. “Yeah, you could buy a house for that,” Horn points out. “But don’t forget I’d sold like 10 million copies of ‘Video Killed The Radio Star’, so I could afford it. And I knew what it could do.

“I think Kate Bush, Geoff Downes [the Buggles/Asia] and Peter Gabriel had them, so I had possibly the fourth. But you see, everyone else was kind of serious with it, where I was having a laugh really. I always remember, just before I bought the Fairlight, the Synclavier people phoned me up and the guy said, ‘Y’know, if you’re buying a sampling instrument, the Fairlight would be alright for gimmicks, but our machine is like a scientific instrument.’ I said, ‘Well I’m going for the gimmicks [laughs].’ And I did buy a Synclavier a few years later, but I never quite got out of it what I got out of that Fairlight.

“I almost immediately gave it to JJ, ‘cause he just devoted his life to it for a while. And because he was a non-musician, he would always approach it from an unusual angle. His idea would be to put a tennis match over something, not an oboe solo or whatever. That was much more fun.”

The tracking sessions for ‘The Look Of Love’ were done at Good Earth Studios in Soho, while the mixing was completed at Sarm East Studios near Brick Lane, using one of the first SSL 4000E consoles in the country. “‘The Look Of Love’ was the first track that I mixed with a computer, because we’d just got the software for the SSL,” Horn recalls. “Gary Langan and [co-engineer] Julian Mendelsohn said, ‘We want to use the computer’, and I was like, ‘Fuck the computer, I hate the computer.’ I’d tried using [Neve automation system] NECAM and it had really screwed me up. So they pacified me and said, ‘Give us, like, five hours.’”

On ‘The Look Of Love’, there was much in the way of ear-grabbing sonic trickery, not least Stephen Singleton’s saxophone parts swathed in AMS digital delay and Lexicon 224 digital reverb. “I said to Gary, ‘You’ve got to get a sound on this record where all that Steve has to do is play one note and it sounds fantastic.’ And he did it. I thought it was amazing.”

In a great example of Horn’s eye for conceptual detail, meanwhile, he insisted that the female voice saying “Goodbye” in the second verse of ‘The Look Of Love’ was recorded by Martin Fry’s former girlfriend who had dumped him. “I did suggest it,” he laughs, “because if you’re gonna do things like that, I just think you’ve got to kind of make them real.”

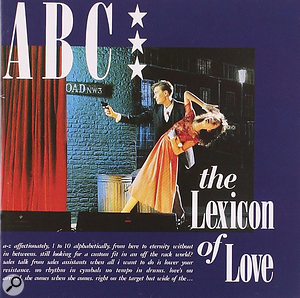

The Lexicon Of Love

From here, Trevor Horn, ABC and the rest of the team embarked on the making of the band’s debut album The Lexicon Of Love, chiefly recorded and mixed at Sarm East. Controversially, however, before work began, Horn suggested that the band replace bassist Mark Lickley with Brad Lang.

“I talked them into getting a better bass player, which maybe wasn’t a kind thing to do,” admits the producer. “I thought that they needed someone more like Bernard Edwards on the bass, and that it would slow the whole process down enormously if we didn’t have that. It wasn’t very fair on the guy who’d been in the band, and in fact it lost me the U2 gig. Bass players in other bands would kind of be a bit scared of me. But Brad Lang was quite brilliant. He was a combination of Bernard Edwards and Jaco Pastorius. When I asked him to come along and play with them, they got it straight away.”

By the time of the album’s recording, Horn remembers, post his sequenced parts ‘tracing’ method on ‘Poison Arrow’, ABC were, along with Anne Dudley, tight enough to lay down most of the backing tracks live. “I don’t remember labouring like hell over anything,” says Horn. “By the time we had Brad Lang and Anne, we had a pretty hot little band. Something like ‘Valentine’s Day’, that’s a live take.”

After a satisfactory take had been achieved, Anne Dudley would get to work overdubbing layers of keyboards. “I was big into proper keyboards,” Horn says, “like the Wurlitzer and Fender Rhodes and grand piano. One of the key sounds on ‘All Of My Heart’ is a Fender Rhodes doubling a grand piano all the way through. The great thing about working with Anne is if she comes up with an idea and you say, ‘I like that,’ she’ll stop and she writes it out very quickly. Other people I’ve worked with — and I’ve worked with some brilliant keyboard players — can occasionally forget what they just did [laughs]. So the piano part that she played on ‘All Of My Heart’ was pretty well worked out and she was capable of playing it exactly the same each time.”

Horn heightened the drama of show-stopping ballad ‘All Of My Heart’ by suggesting the dropdown that comes before the concluding line of the chorus, while on the Motown-ish soul stomper ‘Many Happy Returns’ he edited the multitrack to expand the outro around Dudley’s improvised Fender Rhodes part.

“She just doodled around for a second and I loved it,” he says. “I edited the tape and made the whole section twice as long. The band were away at the time and I just did it. It was quite a complex thing to do because I had to make a copy of the multi track, edit that new section in, and then make it work and play over all the joins. And as I was doing it, the voice at the back of my head was saying, ‘If they don’t fucking like this, it’ll be a real problem.’ But they liked it and I thought, Well, that’s great. I can do this shit and nobody’s gonna complain.”

For Mark White’s guitar parts, the sounds varied from clean and funky to soaked in the latest digital studio effects. “We worked a lot on Mark’s guitar sounds,” says the producer. The [chiming, echoing] one at the start of ‘Date Stamp’ is lovely. We just hung everything on it we could.”

Strings Attached

The string sessions for The Lexicon Of Love, working to Anne Dudley’s arrangements, were done at both Abbey Road Studios and Advision Studios in London. Burned by a bad experience in the past, however, Trevor Horn admits that he took a back seat during this part of the process.

“The last time I’d done strings had been in 1978 on a Bruce Woolley record,” he says, “Our string arranger wasn’t very good and it wasn’t very well written out. But the string players were also a little bit bloody-minded and they literally stopped in the middle of a take as the clock went through one. I was furious. I threw the cheque on the floor in front of the string players, I was so angry with them.

“So when we were doing the strings [on The Lexicon Of Love], I just stayed in the control room and chain-smoked dope [laughs]. It meant that the highs were high and the lows were low! But Anne did a great job of the arrangements. She seemed to understand from quite early on how to write the parts so that the string players could understand what she wanted. It’s getting the expression right, because you’ve got to remember, the string players, they’ve all got to feel it together. If you don’t spot the great take, and you drive them into the ground, they’ll become dispirited just like anybody else.”

Recording Martin Fry’s vocals, Horn — of course a singer himself — tried to make the process as painless as possible for the frontman. “In the Buggles, God bless his cotton socks, Geoff Downes would make me sing one line for two hours, and I found that so depressing that all my joy at singing would go. Martin was still finding himself back then, so because I knew how to use 48 track, I gave him like seven tracks and just got him to sing the song seven times. And, y’know, guided him a bit, but took the pressure off that whole dropping in thing where you’ve got to sing the same word over and over again. I put the vocal together from the tracks and it made vocal sessions better for him. He didn’t dread them.”

Take Two...

The mixing of the elaborately-arranged The Lexicon Of Love was, perhaps understandably, quite tricky. In the end Trevor Horn and Gary Langan were forced to mix it twice. “We mixed and then we cut it,” Horn remembers, “and then I played the cut back and I didn’t like it. I asked for another two weeks. I said, ‘I wanna go back, I know I can get it better.’ It was too soggy-sounding. I wanted to make it more crisp-sounding. So we went back and we just worked harder. Pushed it harder, kind of thing, and were a bit more ruthless. I think the last track we mixed was ‘All Of My Heart’ and the computer broke down halfway through it. I threw a fit, and I said, ‘We’re gonna mix it without the computer.’ We tried that for about five minutes and I realised we had to get the computer working again.”

Horn recalls that the final mix of ‘All Of My Heart’ was completed around midnight on a Sunday, but that when saxophonist Stephen Singleton came in to hear it, he noticed a glaring sonic error the others had missed. “He said, ‘Sounds great, I love the mix, but at the end there’s a funny noise on my sax.’ So we played the multitrack back and we couldn’t hear it. And then we played the half-inch of the mix, and sure enough he was right. There was a little wow. There was a bearing gone in the half-inch machine.

“So we tried to get another half-inch machine at two o’clock in the morning. I remember phoning Abbey Road and the guy goes, ‘Sorry mate, there’s nobody here.’ I couldn’t get any other studio on the phone and there was another session in at Sarm East at nine in the morning — Pete Collins, who produced Nik Kershaw. My wife managed to postpone his session, took him out for lunch and everything, while we managed to get another half-inch and print the mix.”

The mixes on The Lexicon Of Love proved to be as dramatic and dynamic as its songs, with much in the way of volume contrast, and the strings and key drum fills pushed to the foreground. “That’s what we were aiming for,” says Horn. “We were aiming to keep you interested all the way through, not let it flag anywhere. Keep the arrangements exciting, because that’s what Nelson Riddle used to do with Frank Sinatra.”

The Lexicon Of Love II

2016 sees Martin Fry, the sole remaining member of ABC, release The Lexicon Of Love II, working with Anne Dudley and producer Gary Stevenson. Asked recently why he hadn’t involved Horn in the production of the sequel, Fry said, “It would have been wonderful to work with Trevor Horn again, but it would have been a bit like having George Lucas and JJ Abrams in the same room.”

“I’m not disappointed in the slightest,” Horn states. “It would be the kind of thing that either I would be totally involved in or not involved at all. So I’m totally not involved in it.”

As to why both ‘The Look Of Love’ and The Lexicon Of Love have endured as classics, the producer has a simple theory. “You listen to them and you can feel the era,” he says. “And also Martin’s lyrics are just the best. In that genre I’ve not really heard many people say something meaningful and interesting. Let’s face it, dance lyrics were kind of “love to love you baby” and “boogie wonderland”. And you’re talking about lines like “a sunken ship with a rich cargo” [from ‘Show Me’] on a dance record. It was absolutely unique and it caught a lot of people’s imaginations.”

Fairlight Remix

For the 12-inch ‘US Remix’ of ‘The Look Of Love’, Trevor Horn utilised the Fairlight to create a groundbreaking extended mix which chimed with early hip-hop records, using the sampler to bend and ‘scratch’ various elements of the track. “I actually think that was the best 12-inch I ever did,” he says. “Everything kind of came together on that one. What I’d said to JJ was, ‘I want bits of everything on the Fairlight — bits of the strings, bits of the vocal, just anything.’ I seemed to manage to get a narrative through it, playing these things on the Fairlight keyboard.

“Gary was buttoning stuff in and out from the rhythm track to give me some sort of bed to play it over and I was just winging it and doing loads of tries at it. We’d always play it loud, and then get that onto the half-inch tape. It goes ‘goodbye goodbye goodbye’ and I just went mad with things. But it was exciting, and it just seemed to get better and better and then we spent ages editing it from the half-inch into a sort of good shape.”