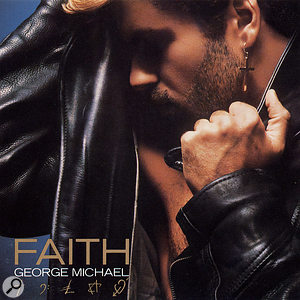

Wham! went their separate ways in 1986, but the triumph of George Michael's debut album Faith in 1987 meant that the success of his solo career was never really in doubt.

Back in 1988, when Faith had turned George Michael into one of the biggest stars on the planet and I lived around the corner from his home in north-west London, I ran into a guy who was a dead ringer for the 24-year-old singer, songwriter, producer and multi-instrumentalist. The thick blonde hair, black leather jacket, white t-shirt, blue jeans, metal-tipped ankle boots, dark shades, designer stubble — this fan had the image down to a tee. But then I did a double-take. The young dude I saw perusing the shelves in a local video store was George Michael, looking exactly like he did on the Faith album cover and in the title track's iconic video. Forget about walking around incognito — the man born Georgios Kyriacos Panayiotou was milking his fame for all it was worth. George Michael on stage during the 1988 Faith World Tour. Photo: RedfernsPhoto: Redferns

George Michael on stage during the 1988 Faith World Tour. Photo: RedfernsPhoto: Redferns

"I went to the States a lot with him when he was working over there and he'd always complain about all of the press attention,” says Chris Porter, whose engineering of Michael's recordings spanned the latter's debut on 'Wham Rap! (Enjoy What You Do)' with Andrew Ridgeley in 1982 through to the 1995 single 'Jesus To A Child'. "I'd say, 'Well, why don't you take off the cowboy hat and dark glasses? If you walk through the airport wearing a raincoat, no one will know.' But he obviously wasn't interested in that.”

The Last Days of Wham!

A Southampton native who relocated to London during the mid-'70s, Porter was a singer in various bands before a keen interest in recording studios and a chance meeting with Phil Lynott resulted in him assembling an eight-track home setup for Thin Lizzy's lead singer/songwriter/bassist. This, in turn, led to an assignment for Porter to carry out some building work for producer Tony Visconti at his commercial facility, Good Earth, and in December 1980, at age 26, he began working there as an assistant engineer.

After an auspicious debut, contributing backing vocals to David Bowie's Scary Monsters, Porter learned miking techniques via morning jingles sessions and assisting on recordings by the Boomtown Rats, Hazel O'Connor, John Hiatt and Modern Romance. Then, while still at Good Earth in 1982, he worked with producer Bob Carter on several projects at other London studios, including Mayfair, where they collaborated on 'Wham Rap! (Enjoy What You Do)'.

"That's when I first met Andrew and George,” Porter recalls, "and then they worked with [producer] Steve Brown to make their first album, Fantastic, recording a few tracks at Good Earth, where I assisted and engineered on some guitar sessions. At the very end of that project, they needed a B-side for 'Club Tropicana' and they had one night to do it. That track was 'Blue (Armed With Love)', and after George and Andrew came to the studio we spent 11 hours trying to build it but never quite finished. To this day, although it ended up as the B-side, I still think it's incomplete. George was the producer — Steve Brown wasn't involved — and that's when our working relationship really started.

Mixer settings and notes for 'Faith'.

Mixer settings and notes for 'Faith'.

"In late 1983 or early 1984, after I'd gone freelance and engineered the Alarm's Declaration with producer Alan Shacklock, I got a call from Wham!'s then-manager Jazz Summers, asking if I'd work with them on their next album, Make It Big. For me, that was a fantastic opportunity. The first track we did was 'Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go', recorded within a couple of days at Sarm West's Studio 2.

"Although there wasn't a demo, George had most of the song written in his head and we recorded it with a live band. Then, for the next track, 'Careless Whisper', George and Andrew went to Muscle Shoals [in Alabama] to work with producer Jerry Wexler and I thought, 'That's it. My involvement with Wham! is over. There's no way I'm ever going to see them again.'

"A few weeks later, I got a call telling me George wasn't happy with 'Careless Whisper' and wanted to know if I'd help him re-record it. Of course, I could, so we went back into Studio 2 at Sarm and worked on that track with a live rhythm section. It took quite a long time to make and we went through 11 sax players to find one who could get the solo's main phrase done in one breath.”

This turned out to be Steve Gregory. The track, subsequently issued as George Michael's first solo single — although among the few written by him and Andrew Ridgeley, and included on Make It Big — also became his first solo chart topper.

"To get away from the press so that George could work peacefully, we went to Studio Miraval in the South of France — where they had the first 3M digital machines — and recorded 'Heartbeat', 'Like A Baby', 'If You Were There', 'Credit Card Baby' and the first version of 'Freedom',” Porter continues. "Most of them were performed with live rhythm sections and all were written by George during the six weeks we were at Miraval — there were no demos for the album. Then we recorded 'Everything She Wants' in Paris and London.

Sarm West, London, where recording of Faith resumed following sessions at Denmark's Puk studios."By the time of Make It Big, Andrew's musical involvement was pretty much non-existent — he was more of an emotional pillar than a musical presence. Meanwhile, George and I always had a really, really good working relationship. Although he's 10 years younger than me, I had a tremendous respect for his ability, his musicality and his drive. He was an exceptionally driven man and had a really clear idea about what he wanted to achieve. It was my first experience of interacting with someone who had songs — and the sounds of those songs — in his head. He'd come to the studio knowing what he wanted to accomplish. That album was really our impression of Motown, and although it sometimes perhaps didn't achieve the sonic quality, it kind of achieved the spirit and liveliness of those records.”

Sarm West, London, where recording of Faith resumed following sessions at Denmark's Puk studios."By the time of Make It Big, Andrew's musical involvement was pretty much non-existent — he was more of an emotional pillar than a musical presence. Meanwhile, George and I always had a really, really good working relationship. Although he's 10 years younger than me, I had a tremendous respect for his ability, his musicality and his drive. He was an exceptionally driven man and had a really clear idea about what he wanted to achieve. It was my first experience of interacting with someone who had songs — and the sounds of those songs — in his head. He'd come to the studio knowing what he wanted to accomplish. That album was really our impression of Motown, and although it sometimes perhaps didn't achieve the sonic quality, it kind of achieved the spirit and liveliness of those records.”

Sarm's Studio 2 was the recording venue for Wham!'s final studio album, Music From The Edge Of Heaven, which evolved out of the chart-topping 'I'm Your Man'.

"That song was put together in much the same way as how the Faith sessions would start out,” Chris Porter explains. "George wanted to be in more and more control of the musicians, directing them as to what he wanted rather than just letting them use their own licks. At that stage, I didn't know the end of Wham! was coming, but he was finding it increasingly difficult to come up with material that suited them. The songs he wrote for Edge Of Heaven had more of a rock element and musical breadth to them, and they were much more complex, exploratory recordings, trying to find a sound. That's when I had to start becoming used to the idea of recalls; of going from one studio to another with time in between and trying to achieve the same results. The SSL desk was invaluable in that regard.”

Puk

The control room of Sarm West's Studio 2.

The control room of Sarm West's Studio 2.

Wham!'s farewell single, 'The Edge of Heaven', topped the UK chart in June 1986, and on the 28th of that month the duo performed their final concert at Wembley Stadium. Bolstered by his solo success and tired of mainly just appealing to the teenage market, George Michael wanted to focus on writing and recording more serious, introspective, edgy material, largely aimed at an adult audience. That August, work on Faith commenced at Sarm. Then, in February of '87, the recording locale switched to Puk, the noted Danish residential facility which, situated an hour's drive from Jutland's largest town of Aarhus, afforded him the privacy and state-of-the-art technology he desired.

"When I saw that amazing studio — partly designed by Andy Munro, with whom I'd worked on a project at Good Earth — I thought it would be perfect for George,” says Chris Porter. "There wasn't much press activity in Aarhus, so we could relax without worrying about him getting hassled. And we could also get straight down to work because everything we needed was in-house: food, accommodation and great equipment, including a 56-channel SSL E Series desk and Mitsubishi 32-track machines.”

Contrary to assertions made elsewhere, a Synclavier 9600 was not utilised for the Faith recordings. Instead, after using Akai samplers to reproduce studio sounds for the subsequent Faith world tour proved to be impractical — "It was impossible for one guy to load enough floppy disks into an Akai between songs,” says Porter — the Synclavier was employed as a much more viable alternative.

That was in February of 1988. Exactly 12 months earlier, the Faith sessions commenced at Puk, where the floor of the main recording area was at about the same height as the top of the console and therefore at eye level to whoever was sitting in the control room.

"It was as if the performers were on a stage in front of us,” Porter remarks. "However, since we never used a live rhythm section, each of the instruments was just overdubbed in there while a LinnDrum and keyboards were recorded in the control room. You see, George's whole angle was to make very limited tracks; limited by his own abilities as an instrumentalist and programmer, using a repeating two- or four-bar drum loop surrounded by quite simple sounds, to create a really sparse background. He could then perform some fabulous vocals against this and focus all of the attention on them.

"With the exception of brass and piano, our soundscape for most of that album was provided by a Juno 106 — for bass and strings — a Yamaha DX7 and a very early 8-bit sampler called a Greengate DS3, with its own sequencing system that ran off an Apple G2. We used that for various percussion samples, including the bottle sound on 'I Want Your Sex'.”

The musicians on Faith included guitarists Hugh Burns, Robert Ahwai, JJ Belle and Roddy Matthews; bass player Deon Estus; keyboardists Chris Cameron, Betsy Cook and Danny Schogger; drummer Ian Thomas and percussionist Andy Duncan. Each of their contributions was overdubbed in order to assemble the tracks in piecemeal fashion, yet it was George Michael who played all of the instruments on 'I Want Your Sex' (Part 1), 'Hard Day' and, with the exception of Matthews' guitar, 'Monkey'.

"While he had the rhythmic ideas and desired feel inside his head, he didn't want the artistry of talented players,” Chris Porter explains. "No matter how good they are, session musicians must be embedded within a particular environment; familiarising themselves with what the producer and featured artist are trying to achieve. In those days, each of those musicians might be working on five or six different things a week, and with them they'd bring a current trend or favourite lick. Well, George didn't want their favourite licks. He wanted his ideas, and that's why he decided to play a lot of the parts himself.

"We would spend a day creating a bass part if he thought he needed to play it himself. It wasn't an ego thing; he was looking for a specific feel and, instead of Deon's expertise and outrageous natural ability, he just wanted something really simple over which he could perform a magical vocal. Then again, a LinnDrum served as the rhythmic starting point for all of the songs, and that's because George didn't want to be bothered with real drummers on this record.

The track sheet for 'I Want Your Sex'."These days, playing with sequencers on stage and in the studio has changed how drummers think about music and impacted the quality of their playing. However, back in the '80s, although they were good, some drummers weren't always able to play in time. On Faith, we recorded tracks over quite long periods of time, and in some cases George would want to change an arrangement after having already done quite a bit of work. That might be pretty difficult if, say, we needed to get the drummer back, match up all the sounds, have him play a different middle eight and drop that in, but it would be very easy with a LinnDrum.

The track sheet for 'I Want Your Sex'."These days, playing with sequencers on stage and in the studio has changed how drummers think about music and impacted the quality of their playing. However, back in the '80s, although they were good, some drummers weren't always able to play in time. On Faith, we recorded tracks over quite long periods of time, and in some cases George would want to change an arrangement after having already done quite a bit of work. That might be pretty difficult if, say, we needed to get the drummer back, match up all the sounds, have him play a different middle eight and drop that in, but it would be very easy with a LinnDrum.

"As George wrote the songs bit by bit in the studio, we went the machine route to get the consistency of sound and rhythm. Over time, the LinnDrum's distinct sound became extremely tedious, but back then it was quite exciting to have that sound, that control and the ability to create individual rhythms that existed in their own right. We weren't trying to make them sound like a drummer; we were just trying to make interesting rhythms that people could dance to. Listening now to the Faith album some things sound pretty ugly, such as the sidestick noises that pop your ears out. Even back then, I thought they sounded awkward, but George liked some of that angularity.

"He has got a naturally very romantic voice; a beautiful high tenor. Yet, on songs such as 'I'm Your Man' and 'Edge of Heaven' he developed this whispered grunt as part of the hard-edged persona that ran through the Faith album with the leather jacket and dark glasses.”

So, which came first: a sound contrived to match the look or the look conceived to match that sound?

"The look followed the sound,” asserts Porter. "We made three or four tracks in that vein before George went to the States and was styled for the album. When we started those sessions he still had his blonde flowing locks, he was clean shaven and he wasn't wearing a leather jacket or pointy boots. That all came later, and George had a huge amount of input creating the new image.”

'Faith'

The recording of the Faith album's title track — featuring a pipe organ intro that resurrects Wham's 'Freedom', Bo Diddley-style rhythm guitar, George Michael's R&B-based vocal and a reverb-laden Sun Records/Scotty Moore-type guitar solo — commenced in May 1987, with Michael playing a two-bar drum loop while Hugh Burns played the aforementioned acoustic rhythm.

"George described the Bo Diddley feel to him, as well as the sequence and the chords,” Porter recalls. "As he didn't really play guitar, he sang the melody and the two of them worked out how it would go. I probably used a Neumann KM84 to record Hugh and double-tracked it, and there's also an electric tremolo doubling the guitar pattern. Deon Estus was there, too, so he laid down some DI'd bass, the authentic-sounding organ intro was produced with the cathedral organ preset on the DX7, and all the while George was singing incomplete lyrics.

"For this and his subsequent albums, George actually wrote the lyrics in front of the microphone. I would start recording, he'd sing a line and then he'd say, 'OK, stop a second. Play that back... Can you drop me in for the word 'the'?' This would be the first time I'd heard the lyric and the first time he'd sung it, and that's how we would build the whole song. Nowadays you can do numerous takes and perhaps use the Melodyne editing program to chop in words, but we did it live and it took many, many hours to complete.

"We'd be dropping in one or two syllables at a time, and that was another reason why we needed to work digitally. Bear in mind, after only hearing the lyric once I'd be dropping in the 'ooh' or 'ah' of a word just so George could get the right emotional effect from the growl or vibrato in his voice, and if I made a mistake I could undo it. People acclaim his great vocal on 'Faith', and it is, but it was studied and worked on to the nth degree.

"The song had this dry, crisp vocal sound, and it had to be set up so it was perfect in his ears. That's how it was for every track. George didn't want just a rough balance to sing to; he wanted to hear exactly how it would sound on the record, with or without delays, dry or with reverb. When he sang to that, if a word didn't have the right consonance or resonance, he'd change the word so that it matched what he wanted to say while also ringing true with the music.

"That had never been the case with Wham!, where the approach was more conventional and lyrics were known in advance. Certainly, he'd been quite concerned about what he heard in his headphones — perhaps more than other people — so that he had a sense of how the finished record would sound, but for Faith every single detail had to be exactly right before George even began recording a vocal. For instance, on 'Father Figure', the delay — which is a consistent feature of the vocal sound — the slight DDL and the reverb all had to be perfect before he began singing and writing the lyrics. Then he might finish for the night and, when he came back to it a couple of days later, it had to sound exactly the same in his headphones so he could continue working on it — exactly the same delay, exactly the same quality of delay.

"That was the biggest challenge for me: making sure everything was precisely how George needed to hear it in order to carry on with the creative process and write the song. In the case of 'Faith', he began by singing in the studio while I applied the usual reverb. Immediately he said, 'No, no, I don't want any reverb for this one. I want it dry and in your face. Have you heard Prince?' Prince had recently recorded a couple of numbers with a very tight delay on the vocals, making him sound growly but dry and aggressive. So, we experimented until we found out how to create that kind of effect.

"I only used a few effects for George's vocals. The Lexicon 224 produced those extended high-frequency pings that you can hear on the reverb-y vocals, and there was also the AMS RMX16 reverb and DMX 1580 delay line. The real characteristic vocal sound right the way through 'Faith' and beyond was an AMS 30-millisecond delay panned slightly left of centre, a 45-millisecond delay slightly right of centre; sometimes with pitch variation on each side, but generally not.

"The microphone he used on that album was a Neumann M49 at Puk that I ended up buying and still use today for quite a lot of vocal work. It's got a nice, controlled top end, so it's not harsh at the top but very, very open. One of the problems with early digital recordings was that you did tend to get quite a harsh top end that was a bit unforgiving. That has improved a lot over the years, but back then the Sonys and even the Mitsubishis had a ceiling on the top end that was almost like a glass wall. I found the M49 gave you a lovely warmth, a lovely depth with a controlled top end, which you could then accentuate without it becoming too metallic and unnatural.”

Sarm West

Shortly after the 'Faith' vocal was pieced together, work at Puk came to an end because, according to Chris Porter, "George started to get cabin fever. So much, in fact, that when he decided to leave and someone told him 'The next flight's not until Thursday,' he said, 'Let's rent a plane.'”

The sessions resumed at Sarm West's Studio 2, where an SSL 4048 E console helped Porter recall every sonic component. "George has great ears,” he states, "and if something was minutely wrong he'd say, 'No, the cow bell doesn't sound the same.' A lot of time was spent matching.”

Such was the case with 'Faith', which wasn't revived until 1st September, 1984, when the song's middle section and Hugh Burns' guitar solo were recorded.

"That solo was put together in three parts in about three or four hours,” Porter recalls. "George wanted a classic 1950s sound, so I used quarter-inch tape delay into a plate, and the solo was then constructed bar by bar in much the same way as he constructed his vocal. There were some tricky drop-ins and two parts had to interplay with each other, but again it sounds very natural and very slick. If you listen to what George is doing vocally behind that guitar solo, he's singing a little bebop riff, and that was his starting point for what he wanted Hugh to play. Hugh, who has an amazing technical facility, tried to combine that with the ethos of the time and came up with a slightly more rolling lick.

"At that point, George asked him to syncopate it a little bit more, he himself sang some of the melody and the whole thing was developed that way. As a musician, Hugh was willing to be the instrument for George so that he could ask him to try out all of these different ideas. And George loved working with Hugh because he was so patient and could produce what he requested. This was done with Hugh standing in front of his amp in the studio and George behind the desk, singing the lines down the talkback.

"At the time, I didn't find the process challenging; I found it interesting and it absolutely filled up every day of my life for about a year and a half. It was so exciting. Still reasonably fresh to the industry, I didn't expect to find myself involved in that kind of success, so it was absolutely brilliant and I loved every minute of it.”

Aftermath

A transatlantic chart topper following its October 1987 release, as well as the first record by a white artist to hit the top spot on Billboard's R&B chart, Faith won the 1989 Grammy Award for Album of the Year, en route to selling more than 20 million copies worldwide. What's more, its four US number ones — the title track, 'Father Figure', 'One More Try' and 'Monkey' — made George Michael the only British male singer to achieve this feat with a single LP.

Those songs were sandwiched between the lead-off single, 'I Want Your Sex' — which, issued nearly five months before the album, climbed to number two in the US and number three in the UK — and 'Kissing A Fool', which was also a Top Five hit in America. Meanwhile, 'Faith', which reached number two in the UK after its October '87 release, was the best selling single of 1988 in the United States and marked the high point of George Michael's career.

"I worked with him up until about a third of the way through the sessions for his third album, Older, at which point he became very interested in the club-type record,” says Chris Porter whose engineering or production credits during the past three decades have also included Gary Moore, Robbie Nevil, Aswad, Dave Stewart, Elton John, Take That, Pet Shop Boys, Tina Turner, Cliff Richard and, recently, Murray Head and Chris de Burgh. Presently, he and Hugh Padgham co-own the Stanley House complex in Acton, West London, where they each have their own studios while 10 production suites are rented out.

"George's sound became much more complex, with multiple layers or synthesizers, beats and loops, ” Porter continues. "Reflective of his nightlife, that's where he wanted to be and he found a bunch of people who were immersed in that kind of music. I wasn't. Having always considered him to be a very romantic singer, I especially love it when he sings ballads, and looking back at the body of work we did together, I'm extremely pleased and proud about my involvement in that part of the story.”

'I Want Your Sex'

'I Want Your Sex', which commenced recording inside Sarm's Studio 2 in August 1986, ultimately comprised three separate parts: the electro-funk 'Rhythm 1: Lust' which was issued as a single; the funk/R&B 'Rhythm 2: Brass In Love'; and, featured separately as the closing number on non-vinyl releases of the album, 'Rhythm 3: A Last Request'. It was, as Chris Porter now recalls, among the more complex tracks that he engineered for George Michael.

"We were working on a song, again we just had the Juno, LinnDrum and DX7, and we'd connected them all up so that we could run them off MIDI. After doing some programming, we returned to the studio the next afternoon, I pressed 'play' on the tape machine, the MIDI obviously wasn't right and everything started making these weird noises. The drums were triggering random sounds on the Juno and DX7, starting to make what you now hear as the intro on 'I Want Your Sex': a strange squelching, pulsing bass sound.

"I went, 'Oh damn, I'll reset it,' and George said, 'Hang on a second, hang on a second! That sounds really good, doesn't it?' I said, 'It's a bit weird,' and he said, 'Yeah, but if we just take a bit out of here and a bit out of there we might be able to use it... ' We recorded a few bars of that odd squelching noise, and it then morphs into the song, at which point the bass becomes the bass part and just the Juno, LinnDrum and DX7 provide the overall soundscape.

"Written in the studio, it took quite a long time to record the entire first part of 'I Want Your Sex', bit by bit, four bars at a time, with George playing all of the instruments. Then, when we got to Puk, he had the idea for Part 2 in his head, to lengthen the story. So, we recorded that with Deon Estus on bass, George on guitar and keyboards, and a seven-piece brass section. This was done in two- to four-bar musical increments, and those brass players weren't always amenable to that approach. Paul Spong and Steve Sidwell were playing trumpet, and working for really long periods of time could get to their lips. Still, we were all young, we were in a fantastic place, it was a creative process and it was really exciting.

"The desk at Puk had 28 channels on either side, so I had the original multitrack on one side and what would be the new version on the other side. I was bouncing from the master over to the slave for the crossover point as the musicians went into this new section, and George would tell them 'Play something like this,' they'd rehearse the part and we'd drop it in. If it didn't work, we'd drop it in again, and then George would say, 'Okay, now what if it went something like this for the next few bars?' After another rehearsal, we'd drop-in those few bars, and that's how the whole thing got built up from beginning to end, over the course of eight or nine hours in a single night.

"By then, Part 1 had already been selected as the next single, but Part 2 added depth for the version that appeared on the album with more of a New York club sound, and then the romantic, altogether smoother Part 3 was my favourite bit... although I can't now remember how it came about.”