Richie Hawtin takes us through a seminal Plastikman album — and its unexpected sequel.

As a world‑renowned electronic music producer and DJ operating for more than three decades, Richie Hawtin has assumed various identities for his releases down the years, including F.U.S.E., Circuit Breaker and Concept 1. But he is perhaps best known for being a pioneer of minimal techno under the most famous of his trading names, Plastikman.

Hawtin’s debut album using that pseudonym was the stripped‑back acid electro of Sheet One, released in 1993. But it was with his third Plastikman album, 1998’s Consumed, that as a producer he perfected a spacious, ambient and hypnotic dance music style that was entirely his own — not least with the polyrhythmic analogue pulsing of its near‑12‑minute‑long title track, ‘Consumed’. As Hawtin tells SOS today, this groundbreaking techno sound arrived as a result of his desire to move away from records made purely for the dancefloor.

“I was kind of bored of DJ’ing,” he admits. “Around ’97 to ’99, there were so many derivative techno records coming out. I was feeling, like, ‘It’s all the same. When’s something going to sound different?’”

For his sleek arrangements on Consumed, Hawtin was inspired by the Kraftwerk, Pink Floyd and Tangerine Dream albums that his electronics‑obsessed father had played around the house as he was growing up, rather than the Detroit techno that fuelled his creativity as a teenager. “Those echoes are 100 percent there in the composition of my albums,” Hawtin says. “The beauty of having an hour‑long listening experience.”

More recently, Hawtin has returned to ‘Consumed’, and its parent album, with 2022’s Consumed In Key, a collaboration with Canadian musician/producer Chilly Gonzales that is described as more of a “reimagining” than a remix record, since it features the latter improvising piano parts over the original tracks. Gonzales has said that the shuffling techno grooves of the original Consumed sounded to him “like some science fiction version of jazz” and so he reacted to that idea in his playing, beginning work on the project before Hawtin was even made aware of it.

“Of course, Consumed is the inspiration for the project,” says Hawtin, “because that’s what Chilly decided to sit down and listen to and play the piano to. But I think somehow it’s morphed into really its own unique space, which perhaps is a planet in the Consumed universe. But it’s definitely not the planet where it first came to fruition.”

Early Days

British‑born Richie Hawtin grew up in Banbury, Oxfordshire and emigrated in 1979, aged nine, with his family to Canada when his father got a job working as a robotics engineer for General Motors. Living in Windsor, Ontario, just a few miles across the river from Detroit, he was in the right place at the right time to witness as a teenager the birth of techno in the US city in the mid‑1980s.

Having been given an 8‑bit Commodore VIC‑20 computer as a kid, using it to initially program games before beginning to experiment with rudimentary sounds, he was comfortable with technology from an early age. As a teenager he began to listen to alternative and industrial music, his portal to dance music being the radio shows of Detroit DJ/musician Jeff Mills, who would mix records by European electronic acts such as Yello and Front 242 in with proto‑house tracks.

Inspired, Hawtin began DJ’ing at clubs in Windsor, even booking Jeff Mills for one event, and meeting other older Detroit techno DJs and producers along the way, including Scott Gordon and Derrick May. His first experience of making dance music himself came when he hooked up with fellow DJ John Acquaviva and began messing around in the latter’s home studio, which featured an Akai S1000 sampler and — set to become a constant piece of kit in Hawtin’s setups — the Roland TR‑909 Rhythm Composer.

Funding a label, Plus 8 Records, from credit cards, the pair scored a European underground dance hit in 1990, ‘Technarchy’, as Cybersonik. At this point, Hawtin set up his own studio in his parents’ home, naming it Under The Kitchen, and filling it with whatever gear he could afford.

“I was a victim of economics,” he laughs. “I bought what I could find cheap. 303s. Of course, people don’t think they were cheap, but they were 50 bucks. 808s, a Dave Smith Sequential Circuits [Pro One]. I didn’t have Moogs, they were too expensive. I didn’t have ARPs, they were too expensive. But I did have a [Korg] Wavestation keyboard, also a Dave Smith co‑design, which gave me a kind of beautiful digital ambience.”

Among the effects units that Hawtin managed to buy at the time were an ART Multiverb and a Yamaha SPX90. “The SPX had a dirty, great flange,” he recalls, “and the ART had the gated reverb that nearly every clap that I ever used back then had on it.”

From here, Richie Hawtin began releasing other records as F.U.S.E. and Circuit Breaker. These tracks, such as ‘Substance Abuse’ and ‘Overkill’, were made by him running sequences from various synths and drum machines chained together and driven by an Atari ST, while he live‑manipulated and effected their sounds. He recorded the jams to DAT, before editing them digitally.

“My dad had an IBM computer,” he remembers, “and there was this great software by Minnetonka called Fast Edit. It was really basic... you recorded it in, and you could just cut and throw away. It was complete destructive editing. But it was very, very fast.

“But I remember when I made the Circuit Breaker stuff, ‘Overkill’ was, like, two DATs long [laughs]. It took you longer to find the good part to edit.”

Around this time, Hawtin was earning a reputation for his own warehouse‑staged club nights in Detroit. But, even with his growing status as a DJ, he felt that his own records were becoming too conventional. “Like F.U.S.E. ‘Substance Abuse’,” he says, “it’s a banger. But it’s like, eight bars in, bring the clap and the acid line in. Okay, take a break, drop the kick, bring it back. Like, it’s a bit more formulaic.”

This led Hawtin towards the more angular and artful sound of Plastikman. “If you look at even the kind of thumping Plastikman tracks from the beginning, like ‘Elektrostatik’ or ‘Krakpot’, I think these are all pretty out‑there tracks. They took a long time to develop.”

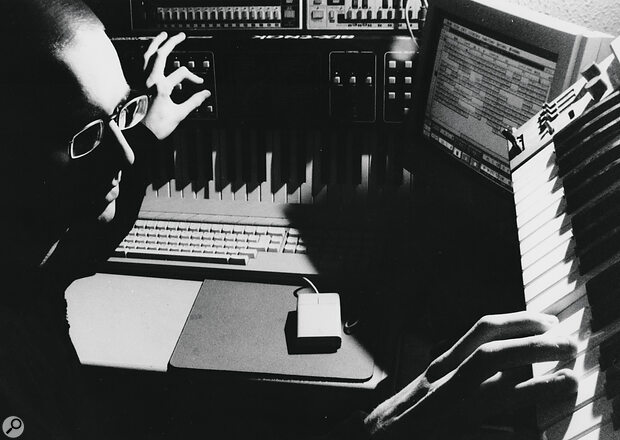

The Plastikman setup circa 1993.

The Plastikman setup circa 1993.

New Studio, New Synth

In 1995, Richie Hawtin set up a new studio, The Building, and began to update his gear. He remembers having typical teething problems with the upgrade. “I moved in there and did what we all do... stupid shit,” he laughs. “I sold my Allen & Heath mixer, a GS[3000] that I’d used to record all my stuff. I bought a Mackie mixer because it was kind of the cool hype thing, and everybody loved it. And I rewired everything to it, made one song, Plastikman ‘Are Friends Electrik?’, which I love, one of my favourite songs ever. But it was the only song that I recorded that sounded good. Everything else sounded shit. And it was just something to do with the bass undertones on that mixer.

“So, ’95 was kind of me figuring out that new studio, selling my stuff, rebuying back another Allen & Heath [laughs], changing amps. I’d gone from a little Tannoy System 8 with dual concentrics to the System 15s with subwoofers. But then I realised that the subwoofers actually gave me too much bass. So after that was all done, it was ’96 and that studio was just humming.”

Hawtin’s main — and most expensive — purchase at this point was a Serge modular synth system. “That was a moment when I was looking at ARPs and everything,” he recalls. “And I was like, ‘Fuck this, if I’m going to spend a couple of thousand dollars, I should be buying an instrument that nobody else has, or nobody really knows.’”

Serge modular synths were originally built in the ’70s, but Hawtin invested in the STS Serge rebuilds made by Rex Probe in the early 1990s. “I went and met Rex Probe down in Berkeley,” Hawtin says. “I loved that it was built new, but it was still kind of old techie circuitry. It was something different. Now you say you have a Serge and people are like, ‘Wow, that’s so cool.’ But back then, when you said you had a Serge, even the normal synth‑head kind of looked blankly at you like you were speaking a different language.”

Another important addition to Hawtin’s setup was his acquisition of a Doepfer MAQ16/3 MIDI analogue sequencer (used by Kraftwerk and Jean‑Michel Jarre). “I had one Doepfer MAQ16/3, an original black one. I loved it so much that I went out and I bought three of the newer editions. Those were usually used on separate lines. So that’s nine different CV and MIDI 16‑step sequences, which would be going, more often than not, via [additional] CV patches, to opening up Serge modular parameters.”

Richie Hawtin’s first project in his new studio was an ambitious one — a 12‑inch release every month for a year under the name Concept 1. “Concept 1 was my departure from worrying about making dancefloor music,” he says. “My challenge was to be able to make something every day. Actually, if you listen, they’re very simple things, y’know, kicks and percussion going through Serge filters. There’s even a couple of non‑Roland drum sounds which were all coming from a Kawai XD‑5 [drum synth module]. Sometimes it would be, like, 20‑, 30‑minute jams. The whole year of ’96, Concept 1 gave me the confidence and experience for what Consumed would be.”

Richie Hawtin: “I had one Doepfer MAQ16/3, an original black one. I loved it so much that I went out and I bought three of the newer editions."

Hypnotic Grooves

Even if the gear that Richie Hawtin used for Concept 1 and on Plastikman’s Consumed was far more sophisticated than anything he’d ever previously utilised, he was still a stranger to multitrack recording. “Consumed comes from a time where many of us electronic musicians didn’t have the knowledge of multitrack recording,” he stresses. “Everything was recorded as a live jam to 2‑track DAT.”

Hawtin’s daily working method during this time involved him firing up his equipment at the start of each session and trying to immediately find a hook.

“All my stuff is mostly created on a groove,” he says. “Even if that’s a melodic 303 line. I don’t necessarily mean a groove that gets you dancing. It’s something that is maybe more hypnotic. Whether it’s a drum track or an acid line, you get something that you’re kind of grooving to and listening to for 20 minutes, and you felt like it was two minutes. You just can’t get enough of it.

“Then once you’re in that moment, you grab it and record it, before you get tired of it. Before you think, ‘Oh, could this be better?’ and then you fuck it up and you’ve lost it. So, things happened very fast, as in I would write a track and record a track in the same day.”

Central to his setup was the 909, by this point often used more as a sequencer than a sound unit. “Sometimes the kicks or other sounds were either coming from an [Akai] S3000 or from the Kawai [XD‑5]. But those would have been sequenced from the 909. The 909 has a certain feeling in its rhythm. A big trick was using the 909 as a one‑note sequencer. That came from the days when I was using the [Roland SH‑]101 a lot and you would use a rimshot as a trigger out.”

The shuffle function on the 909 was the key to some of the distinctive grooves on Consumed. “Well, y’know, I’d done a number of kind of house‑y records, like Robotman ‘Do Da Doo’ [1993], and I always liked the 909 shuffle. It was usually shuffle at number three, so it’s just slight. I was also using triplet delays to give a different kind of syncopation. Like, honestly at that moment, I was just looking to have the music sound and feel different than what I’d done before.”

Hawtin was also particularly fond of the slight tempo fluctuations he felt he could hear happening between his hardware machines, believing they gave his grooves a more human feel. “This is the most difficult thing with going into computers as your main tool,” he argues. “Because all the plug‑ins basically end up — unless they’ve been made by really fucking cool people — all just following the same clock. And so everything is in time too much. Whereas when you’re using hardware, sometimes these slight fluctuations — very, very, very slight, so something you may not even be able to measure — you can feel somehow. That gives your music a bit of its own heart and soul.”

Hawtin also employed irregular step patterns, sent from his Doepfer MAQ16/3 to his Serge modular, which were to be a central feature of the rhythmic style of Consumed. “There would be a lot of cyclical five‑note patterns, 12‑note patterns that were all kind of moving and opening up filters and things at certain times,” he explains. “Consumed is an album of feedback. Everything was cross‑modulating everything else.”

One Take

For Consumed, the tracks were recorded in the same sequence in which they appeared on the album, and all in a single day apiece. The one exception was its title track.

“I remember being so happy and excited with myself,” Hawtin says of the initial creation of ‘Consumed’. “The melody — bom‑bom‑bom, bom‑bom‑bom — was like a lot of my stuff where I don’t really write melodies. I write rhythms which are kind of like melodies and that’s just a tom/conga sound from the Kawai drum machine, which I slowly opened up and closed through a Serge filter with a lot of effects.

“It was all about all these reverbs and delays and you have this XD‑5 line coming up with lots and lots of reverb. The Allen & Heath mixer had MIDI mute automation, and so I had a loop going in the Atari ST that was basically just eight or 16 bars. So, I’d let all the effects play, and then in one set instantly turn off the effects, and then eight bars later turn them back on.

I left it going all night. I left all the machines running, because I didn’t want to lose anything, and then I recorded it the next morning to get the final cut. Everything was recorded live and in one take.

“I was just listening to that and I had it cranked. I remember going upstairs, and downstairs [in the studio], every time the reverb turned off it was like, ‘Wow, what a fucking powerful moment.’ That was the last song I recorded for Consumed and it was the only song where I made it one day and I left it going all night. I left all the machines running, because I didn’t want to lose anything, and then I recorded it the next morning to get the final cut. Everything was recorded live and in one take. There was a couple of edits here and there, but you had to nail it, or you were fucked. There was no going back.”

By this stage, Hawtin was using Sonic Foundry’s Sound Forge program to edit his DAT jams. “Consumed would have been edited on Sound Forge, but I didn’t even like to use the playlisting function. It would just be like, ‘Okay, this part is a good beginning, this middle part needs to be shorter, cut. And this ending over here is good... done.’”

Ten minutes into ‘Consumed’ there’s a section where a Serge modular riff cracks up and distorts. Hawtin chose to leave the skronky sound in the final cut. “I just liked the way it was feeling,” he says. “That was just too much resonance on a filter, and that’s how it was recorded.

“It’s funny, because when I was listening to it again [recently] and remixing, I did notice that that was really pushed. But that’s the way it is. I will not say I’m the best mixer or engineer in the world. I’ve learned everything as I go, and I just have a particular ear and I try to make things that made me feel like, ‘Fuck, that sounds great.’ And there’s not really a technical consideration. It’s just like, ‘Does that sound good to me?’”

Consumed In Key

For their 2022 Consumed In Key collaboration, Richie Hawtin and Chilly Gonzales worked remotely, their go‑between being a mutual friend, Canadian producer/DJ Tiga. Gonzales had first begun by recording his piano parts over MP3s of the Consumed tracks and Tiga then sent Hawtin three tracks for his consideration.

“The first three tracks were ‘Contain’, ‘Consume’ and ‘Locomotion’, which are kind of the core of Consumed,” Hawtin says. “I thought they were respectful somehow and then extremely disrespectful sometimes because I was still listening to it like, ‘Somebody is playing on top of my album [laughs].’

Chilly Gonzales and Richie Hawtin collaborated on 2022’s Consumed In Key album.Photo: Camille

Chilly Gonzales and Richie Hawtin collaborated on 2022’s Consumed In Key album.Photo: Camille

“But the big thing for me was that I’d never met Chilly Gonzales. I didn’t know much music by him, but I knew the figure of Chilly. I knew he was well respected. He was a serious musician and he had done a lot of serious compositions. And I thought, ‘If this guy sat down in his own time and recorded this, I need to respect and listen to it, and give it a lot of deep thought about where this is coming from, or where it may lead.’

“Then, more so out of the respect for Chilly as a musician, I said, ‘Let’s go with this.’ I wouldn’t say it was on the strength of those first demos. It was partly due to that, but it was as much weighted on who Chilly was and what I thought he would be able to deliver in the end result.”

Hawtin’s only stipulation was that he had control over the final mixes. Once he’d been sent pre‑mixed WAV stems of Gonzales’ piano contributions, he returned to his original equipment to try to blend the new parts in with the mastered stereo Consumed tracks.

“I hooked up the originals,” he says, “and the only pieces of the puzzle that I could really remember, because I had some notes from the Consumed times. I had the effects patches for the Lexicon [PCM90] and the Roland SRV‑330 [Dimensional Space] reverb and the [Ensoniq] DP/4 [Parallel Effects Processor]. So I hooked all those back up and started sending Chilly’s piano through those.

“I’d never mixed piano or acoustic instruments and I told the guys, ‘That can be my contribution... to give a bit of my sonic imprint into this new project,’ because I mix and hear things in a certain style. So I sent everything through the effects, and I did a first version where it was, like, piano through reverbs. And it really sounded like the piano was in there from the very beginning. I thought it was amazing.”

Unfortunately, Gonzales, who favours what Hawtin calls a “hyper‑realistic piano style”, didn’t agree. “That became a learning point and even a struggle point between Chilly and I,” Hawtin admits. “Because I was bringing his work into the world of digital effects and experimenting with some things which, in the end, I can see why they didn’t work. They were necessary experiments for me in the mixing process, but they were things that Chilly strongly disagreed with at the beginning of that process [laughs].

“When the mixing happened, I really went to the other extreme. As I listened more and more in solo to Chilly’s work, I started to learn about Chilly. And that, in the end, turned my effects idea upside down. There are still some residual effects that I left in there, although it’s very subtle. But the process was really exciting, to learn by listening and find out how these two sensitive frequency arrangements came together in a harmonious way with basically nearly zero verbal communication.”

Of the new versions, Hawtin singles out ‘Locomotion (In Key)’ as his favourite. “That always had a great momentum, but the way Chilly played the piano... it’s like a steam engine. It’s like there’s these two trains next to each other... one’s nudging and then the other’s nudging. They’re competing with each other, but they’re on the same mission and on the same path. There’s this duet going on. I think that’s really a beautiful moment.”

Studio Evolution

In terms of his studio setup these days, Hawtin is moving further away from hardware and more into software, Bitwig Studio being his preferred DAW. In fact, he recently worked with Bitwig on custom scripts to enable him to better interface his Novation Launchpad Pro and Akai Fire with the software.

“Last year and the year before, as I moved from a mostly analogue and sometimes hybrid studio setup to a complete digital setup with Bitwig, I spent a couple of months researching and playing with my original setup with the 909s, and all of the things that we’ve spoken about... like using a 909 to sequence.

Despite being mainly computer‑based today, Richie Hawtin’s studio remains a home for his impressive collection of hardware.

Despite being mainly computer‑based today, Richie Hawtin’s studio remains a home for his impressive collection of hardware.

“I developed some custom scripts that gave me some of those flavours and some of those functions that I didn’t find on any other controllers for Bitwig or Ableton. So, I’m hoping that these will also help other musicians find their own new or potentially better ways to connect with the computer and feel that there’s a nice human interface.”

Not that Hawtin has ditched all of his other hardware, though. “No, no,” he insists, “it’s all in my studio because I do find it quite alluring. And I do like all the lights and the warmth that it gives my studio in the winter months. Just sitting in front of a computer is still a little bit uninspiring for me. But I think you’ll see more custom script design.”

Similarly, Hawtin co‑designed the Model 1 analogue DJ mixer, along with engineer Andy Rigby‑Jones. Made with what he calls “a DJ/producer mindset”, it enables the user to live‑sculpt EQ moves using the high‑ and low‑pass filters that have increasingly become essential to dance music.

“It was important that the Model 1 transcended just being a mixer,” he says. “Because the original intention of a mixer was just to mix some signals together. But I think DJs took the mixer idea and helped develop it into what became an instrument. And with that in mind, I wanted to make, with Andy, something that was an instrument designed as a mixer rather than a mixer hoping to become an instrument.”

Elsewhere, Hawtin has been busy exploring other synthesis platforms. “There’s a really interesting project called Audioglyphs, which is a web interface into web audio components to make generative music out of a kind of node‑based graph system, which I’m learning and experimenting with now. And I’m also teaching myself the new synthesis engine in Unreal 5 called MetaSounds. I don’t know where this will take me. But I think it’s very interesting to experiment and learn new techniques.

“One of the most exciting times for me,” he adds, “was when I was making Consumed or Sheet One, and I didn’t know all the things I was doing. I was still learning as I was going, and there were surprises happening. People have asked me, ‘Hey, why don’t you just plug your 909 and 303 in?’ I can’t do that. I love those machines. But I need to feel like I’m sitting in front of a 909 and a 303 again for the first time. And so the only way to do that is to not sit in front of a 909 and 303 again.”

The Future Of Plastikman

Richie Hawtin — who has now moved to Portugal after some years spent in Berlin — has periodically revived the Plastikman name down the decades, most recently with the 2014 album EX, recorded live at the Guggenheim Museum in New York. For him, Plastikman seems to represent a freewheeling creativity that he finds himself drawn to again and again.

“All the research and development I’m doing right now is based upon the assumption and the hope that I will be deep into a new, multi‑faceted Plastikman album. I think Plastikman has always had more sort of freedom in there. It’s just about letting something happen freely, spontaneously, and, in a way, introvertedly. It’s like, ‘Where’s my head at?’ and I try to record that.

“That’s probably as close to a description of Plastikman as you’re going to get.”