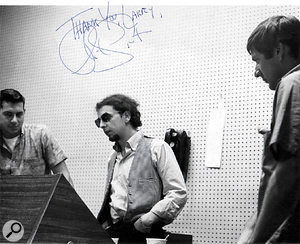

Phil Spector with engineer Larry Levine at the custom-made 12-channel mixer in the control room at Gold Star. In the background you can see the three-track Ampex 350 tape recorder on which all early 'Wall Of Sound' recordings were made.

Phil Spector with engineer Larry Levine at the custom-made 12-channel mixer in the control room at Gold Star. In the background you can see the three-track Ampex 350 tape recorder on which all early 'Wall Of Sound' recordings were made.

Phil Spector was one of the first producers to realise that a recording studio could be an instrument in itself - and the sound he created over 40 years ago has influenced popular music ever since.

Writer Tom Wolfe labelled him The First Tycoon of Teen, many of his work colleagues described him as a genius, and assorted others asserted that he was a certifiable lunatic. Phil Spector was all of these and more during his heyday in the early '60s, writing and producing a string of classic pop singles that introduced the world to his famed 'Wall of Sound' while directing a stable of highly talented artists in an autocratic style reminiscent of movie dictators like Cecil B DeMille.

Introductions

Harvey Phillip Spector was a troubled kid who turned into a brilliant music mogul before his mind turned in on itself. In 1950, when Phil was nine, his father shot himself, and eight years later the teenager adapted the epitaph on his old man's tombstone for the title of his first hit record. 'To Know Him Is To Love Him' was a US number one for the Teddy Bears, a trio that featured Spector on guitar and backing vocals, and shortly thereafter the native New Yorker pursued a full-time career as a songwriter and producer. Among his early successes was the soul smash 'Spanish Harlem', co-written with Jerry Leiber and recorded by Ben E King. In 1961, after producing hits for artists such as Gene Pitney, Curtis Lee and the Paris Sisters, Spector formed his own Philles record label with Lester Sill and began turning out what he'd later refer to as "little symphonies for the kids".

This wasn't hyperbole: many of these songs, featuring the vocal talents of Darlene Love and girl groups like the Ronettes and the Crystals, were three-minute masterpieces of timeless pop art. Working inside Hollywood's Gold Star Studios with a large assembly of crack session musicians that drummer Hal Blaine dubbed the Wrecking Crew, Spector applied massive amounts of echo to multiple instruments and fused the individual components into his unified 'Wall of Sound': a brilliant, seamless amalgamation of guitars, bass, keyboards, drums and percussion with woodwind, brass and string orchestrations that reached its apotheosis on such classic tracks as the Crystals' 'Da Doo Ron Ron', the Ronettes' 'Be My Baby', the Righteous Brothers' 'You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin' and Ike & Tina Turner's 'River Deep, Mountain High', as well as the landmark album A Christmas Gift For You From Phil Spector. And there behind the board to realise Spector's unique vision throughout his halcyon years in the '60s was Larry Levine, who had commenced his engineering career at Gold Star a couple of years after the studio had been founded by Dave Gold and Levine's cousin, Stan Ross, back in 1950.

Gold Star

Initially just a one-room facility, Gold Star boasted a second room but was still little more than a demo studio when Levine began recording Eddie Cochran there in July 1956.

"That started out as Eddie recording demos for the American Music publishing company and evolved into us working on all of his hit records," says Levine, referring to 'Twenty-Flight Rock', 'Summertime Blues', 'C'mon Everybody' and the posthumous UK chart-topper 'Three Steps to Heaven'. And while Stan Ross engineered the Teddy Bears' 'To Know Him Is To Love Him', Levine also has a very distinct recollection of encountering Phil Spector for the first time during that July 1958 session.

"I saw him come in and I took an immediate dislike to him," he remarks. "His demeanour kind of rubbed people the wrong way. It wasn't anything that he did. It's strange, but there's an aura about some people. Things happened that he didn't cause, and although there was a sense of him being arrogant, after getting to know him I realised that wasn't so."

Stan Ross was again the engineer when Spector returned to Gold Star in July 1961 to produce the Paris Sisters' 'I Love How You Love Me', but Levine got the gig when the diminutive producer was back there exactly 12 months later for 'He's A Rebel', Spector's second US chart-topper, with Darlene Love taking care of the lead vocal while fellow Blossoms Fanita James and Jean King sang backup.

"Stan was away on vacation," Levine recalls. "Then, three weeks later, Phil came back to do 'Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah' [with Bob B Soxx and the Blue Jeans, comprising Bobby Sheen and the aforementioned Blossoms]. 'He's A Rebel' was not the Wall of Sound, but that next record was, and Phil picked Gold Star as the studio to achieve that after having worked in New York [at both Bell Sound and Mira Sound Studios]. He hated to fly, so he would have done anything to avoid flying, but he told me 'I heard the sound of the studio when we did "He's A Rebel", and I knew it would enable me to do what I want to do.'"

Laying Foundations

"If any one recording projected me into what I became it was 'Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah'," continues Levine, "and Phil would have worked with Stan on that, but Stan didn't want to work on the weekends, so he made some excuse and Phil used me again. We were into that session maybe three hours or so, and I was following Phil's instructions to raise this and bring that up, but then it got to a point where I knew I couldn't record the track because all of my meters were pinning right at the top. If I'd have put that on tape it would have distorted. As a matter of fact, I found out later that there were other engineers along the way who tried to duplicate the Wall of Sound by turning up all the faders to get full saturation, but all that achieved was distortion. In this case, I just had no room to work, and I knew what I had to do. I actually didn't have the nerve to do it, but finally I thought 'To hell with it,' and I turned all the faders off. First, Phil looked at me, and then he started screaming at me like I was crazy. He said 'How can you do that? You can't do that! I just about had the sound I want!' I said 'Well, I couldn't record it, Phil.'

"At that point I started bringing in one microphone at a time and balancing it at a level that I could record. We had 12 inputs on the console that Bill Putnam had built over at United Western with help from Dave Gold, so I had 11 microphones turned on, and the only one that wasn't belonged to Billy Strange's lead guitar. Phil said 'That's the sound, that's the sound! Let's record it!' I said 'Well, I don't have Billy Strange's microphone turned on,' and he said 'Don't turn it on. That's the sound I want to record.' As it happens, you can hear Billy Strange's guitar throughout, but it wasn't miked. It just bled onto the other mics.

"Until then I hadn't even heard the name of the song being mentioned, so when I went to slate it I asked Phil what the name was, and when he said 'Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah' I thought he was faking me out. When I found out that it really was 'Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah', I nearly fell out of my chair. At any rate, we did it in one take."

Thereafter, the modus operandi was largely always the same, with Spector rehearsing the assembled musicians for several hours before Levine rolled tape, and then the backing track being performed live and recorded monaurally via the aforementioned console and Ampex 350 three-track tape machine, monitored with Altec 603 speakers. (A bass drum overdub on 'Da Doo Ron Ron' was the exception to the rule.)

"Phil's routine almost never varied," says Levine. "He would start off with the guitars — usually three or more — and have them play the figure that was written on the lead sheet. Jack Nitzsche built the lead sheets, and that was the thing — it all got built. I'm not sure that Phil had the sound in his mind as to the finished product. He would have the guitarists play eight bars over and over while the rest of us were listening, and then he might change the figure. Once he thought it sounded OK, he would bring in the pianos. Then, if all of that didn't work together, he'd go back to the guitars, return to the pianos, and when everything fit he'd bring in the bass. He always brought in the instruments piecemeal in the same way, and the guy who worked the least on all of those sessions was the drummer Hal Blaine, because he didn't come in and start playing until everything else was right. Then, when he did play, it was magic. He didn't play his instrument, he was part of it. He totally owned those drums."

The Studio Is An Instrument

During the early '60s, Phil Spector's Wall of Sound was so different to anything previously heard that it may well have prompted certain engineers to panic or protest. Larry Levine was totally receptive.

Spector and the Ronettes after a session in Gold Star's live room. In the foreground is a Neumann U47 used to record Ronnie's vocal parts. Also visible in the background is an RCA mic and one of a pair of huge Altec monitors.Photo: Ray Avery/Redferns"It was the greatest thing that ever happened to me," he says. "After we recorded 'Zip-A-Dee' in one take and then added the voices, I did my mix of the voices against the track and I know I started it off with the voices a little too low. Then I wanted to make another mix with the voices a little higher, but Phil said 'No, that's good,' and that was it. Everything was done in one mix, and the sound was so unique that, when Phil took a dub back to New York, people would come into the studio and I couldn't contain myself. I'd say 'I'm gonna play a tape for you, and if you tell me there is a chance that this won't be a Top 10 record, I'll eat the tape.' They'd look at me like I was crazy.

Spector and the Ronettes after a session in Gold Star's live room. In the foreground is a Neumann U47 used to record Ronnie's vocal parts. Also visible in the background is an RCA mic and one of a pair of huge Altec monitors.Photo: Ray Avery/Redferns"It was the greatest thing that ever happened to me," he says. "After we recorded 'Zip-A-Dee' in one take and then added the voices, I did my mix of the voices against the track and I know I started it off with the voices a little too low. Then I wanted to make another mix with the voices a little higher, but Phil said 'No, that's good,' and that was it. Everything was done in one mix, and the sound was so unique that, when Phil took a dub back to New York, people would come into the studio and I couldn't contain myself. I'd say 'I'm gonna play a tape for you, and if you tell me there is a chance that this won't be a Top 10 record, I'll eat the tape.' They'd look at me like I was crazy.

"Everyone would strive for true sound when recording, and although the control room wasn't truthful, it was the most exciting sound I or anyone who came in had ever heard, and no one told me to eat the tape. Later, when he got back, Phil told me 'You know, I had to put this record out because everyone in Hollywood has heard it! You played it for everybody!' He also said that when he was in New York and played the track for some publisher out there, after four bars of the intro the guy stopped the phonograph and said 'I'll give you $10,000 up front just on what I've heard.' It was that unique."

Not that Spector ever explained his concept to Levine or what he was trying to achieve in terms of the instruments meshing into one another.

"I'm not sure that he [initially] knew enough about that to articulate it," the engineer says. "He knew what he wanted to hear, but then Phil was pliable, too. He was amenable to hearing something that he didn't expect and accepting that. You see, I kind of put producers into three categories: the most difficult producer to work with was the one who didn't know what he wanted and couldn't articulate what he was looking for; next best was the one who didn't know what he was looking for but was open to ideas and could communicate; and then the best to work with — which included Phil — was the one who knew what he was looking for and could communicate this.

"I was always following Phil's directions — if he wanted more guitars he would tell me, if he wanted more echo he would tell me — and I think the biggest part I played was to serve as his sounding board. When we were in the control room, he would ask me endlessly 'What do you think? What do you think?'and I'd say 'I love it.' There was one song — I don't remember what it was — that I kept telling him I loved, and then I guess he asked one time too many and my answer was not positive enough, and that was the end of that track. He trusted me, that was the thing — at least after a while — but he didn't trust me to make an edit. If there was a mistake anywhere along the way in a recording, he'd want to redo the whole thing. He'd had a bad experience with people editing."

That was until Levine managed to duplicate part of a Blossoms recording that he'd mistakenly erased and then spliced this back in. Thereafter, edits were allowed.

Echo Chambers

"Phil wanted everything mono but he'd keep turning the volume up in the control room," Levine recalls. "So, what I did was record the same thing on two of the [Ampex machine's] three tracks just to reinforce the sound, and then I would erase one of those and replace it with the voice. The console had a very limited equaliser for each input — there was a low-end setting for 60Hz or 100Hz, and you could reduce that by 3dB or 6dB, or boost it by 3dB, 6dB or 9dB. Then, on the top end we had 3kHz, 5kHz and 10kHz, and you could increase those in 3dB increments up to 15dB.

"That was basically it in terms of effects, aside from the two echo chambers that were also there, of course, directly behind the control room. There was a crawl hole in the back wall that would allow us access to the chambers, and when we first got them we put a ribbon microphone in there with a little eight-inch speaker, and that was it. I remember it was spooky just breathing and speaking in there, but it was perfect for what it was. If it had a shortcoming, it was maybe a little bottom-heavy for some music, but otherwise it was terrific. Later on, everybody had a split off the inputs and sent the signal to the echo chamber, and the level determined how much echo they would get. However, at Gold Star there was a relationship between the presence and the echo — if you added level to the echo it would reduce the level going directly into the console, so there was a spatial effect, and that worked really well."

Since the typical line-up on a Spector session during the early '60s comprised a drummer, two bass players, three or four keyboard players, four guitarists, three or four reeds, two trumpets, two trombones and any number of people who could help out on percussion, the results were pretty astounding, not least because Studio A at Gold Star measured just 19 by 24 feet, with a 13-foot-high ceiling.

"I remember new clients showing up, as well as some of the songwriters Phil worked with in New York, and they couldn't believe what they saw," Levine says. "They'd heard this huge sound and got a picture in their minds as to what the room must be like, and it was so much smaller than anything they'd previously worked in."

Da Doo Ron Ronettes

Arguably the first really legendary 'Wall of Sound' track was 'Da Doo Ron Ron', written by Spector with Brill Building wunderkinds Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich, and recorded by the Crystals in March 1963 with the lead vocal of Dolores 'La La' Brooks replacing one originally recorded by Darlene Love. Sonny Bono, who was then a Spector sidekick, would later recall: "It took me some time to understand that when Phil asked 'Is it dumb enough?' what he really meant was 'Is everybody going to get the simplicity of this? Will the simplicity of the hook cut through everything and grab them?' Spector knew when he had a song that was going to strike paydirt. His ear seemed infallible. I was standing beside him as the final playback of 'Da Doo Ron Ron' finished. Phil pointed to the speakers and flashed me a sneaky smile. Trying to impress him, I said 'Man, that sure is dumb enough.' 'No Sonny,' he said, 'that's gold. That's solid gold coming out of that speaker.'"

And it was, riding to number three on the US chart and number five in the UK. Yet, if that seemed like a hard act to follow, Spector, Greenwich and Barry outdid themselves just a short time later when they wrote 'Be My Baby' for The Ronettes, a Harlem-based trio consisting of lead singer Veronica 'Ronnie' Bennett, her sister Estelle and their cousin Nedra Talley. Formerly named Ronnie and the Relatives, they had performed in DJ Murray the K's rock & roll revues at the Brooklyn Fox theatre and released some unsuccessful singles on the Colpix label prior to signing with Philles in March 1963. Their first recording with Spector, 'Why Don't They Let Us Fall in Love', then remained on the shelf while he tried to come up with more bankable hit material, and within a few months Ronnie was learning the words to 'Be My Baby' which would eventually hit number two on the American charts and number four in the UK.

A heartfelt Kennedy-era paean of love, lust and seduction, from its unmistakeable boom-ba-boom-pah drum intro through two minutes, 40 seconds of yearning vocals, tension-building pauses, and strings and horns that meld with claps, castanets, Hal Blaine's machine-gun breaks and Phil Spector's Wall of Sound, 'Be My Baby' is one of the finest — some, including Brian Wilson, say the finest — recordings in all of popular music. The producer himself described his philosophy as "a Wagnerian approach to rock & roll". "I was looking for a sound," he explained the following year, "a sound so strong that if the material was not the greatest, the sound would carry the record. It was a case of augmenting, augmenting. It all fitted together like a jigsaw."

In this case, the material was superb and its assembly made it great. Two drummers took part in the July '63 session; Hal Blaine and, Levine surmises, Earl Palmer. Carol Kaye and Ray Pohlman probably played bass. Any three of Leon Russell, Al Delory, Larry Knechtel and Don Randi would have played keyboards, and then the four guitarists were drawn from a pool that included Billy Strange, Tommy Tedesco, Barney Kessel, Gene Estes, Michael Deasy, Dennis Budimir and Glen Campbell.

Sonic Bricks & Mortar

"Friends or admirers of Phil would show up to see and hear what was going on," Levine recalls, "and most of them would invariably end up in the studio playing percussion or some other instrument. Because the room was so small, I was always going to get drum leakage in all the other microphones, particularly the acoustic guitars'. So, what I'd do was mic the drums minimally with Neumann U67s overhead and RCA 77s on the kick just to get enough presence, and then it was a continual process of re-balancing as each instrument was added [to the line-up]. Because the drums weren't the focal point, the choice of microphones we used on them wasn't so critical — we had a great drummer and he had a great sound."

Levine, Spector and Sonny Bono at the desk — signed 'Thank you Larry' by Spector.Photo: Ray Avery/Redferns

Levine, Spector and Sonny Bono at the desk — signed 'Thank you Larry' by Spector.Photo: Ray Avery/Redferns

Not that this was always enough. Spector himself once commented "In those days if I couldn't get a drum sound I'd go crazy. I'd go out of my mind, spend five or six hours trying to get a drum sound."

Levine concurs: "The drums were the bane of Phil's existence. He'd keep saying, 'In Detroit they've got the drums nailed down and they always sound the same.' I could never get them to sound the same. It was always work getting the drum sound right: to get it sounding like it was coming from Hal and not just a roomy sound. That depended a lot on what key the other musicians were playing in. For instance, if the acoustic guitars were playing a lot of open strings, their sound would be stronger and so there would be less leakage in their microphones, whereas the opposite would be true if they were playing in a key where the sound wasn't as strident. It was a precarious balance, and Hal and Earl and all the guys who played drums were always really cooperative if I asked them to tone it down a little bit.

"You see, I never wanted all the bleed between instruments — I had it, but I never wanted it — and since I had to live with it, that meant manipulating other things to lessen the effect; bringing the guitars up just a hair and the drums down just a hair so that it didn't sound like it was bleeding. If they had to change something then I had to change something. If I needed more mic inputs, I'd often tie the acoustic guitars together because they gave the sound part of its structure and didn't need to be heard individually. They were just some of the bricks in the wall, so to speak, and I could therefore get away with doing that, although I also remember one time when I ran out of microphone inputs and one of the acoustic guitars had a mic that wasn't plugged in. I said to Phil 'You know, we're not hearing him. You may as well send him home,' and he said 'No, it sounds right. He stays.' There was no way that acoustic guitar could be heard without a microphone."

42 Times Over

But what of the widely reported image of Spector as mad dictator, relentlessly working his musicians beyond the point of exhaustion and refusing to given them even a few minutes' break? Levine insists this is inaccurate.

"It wasn't because he was a taskmaster, but he just felt that if the guys moved they'd shift the microphones and we'd never get them back to the same exact position," he says. "The sound depended on that, so he hated to give breaks, and he'd try to put this off as much as he could. Still, he did give them, and his admonition was always 'Don't touch the microphones.' That having been said, while he did have a remarkable ear, it was strange because the things that upset him were not necessarily wrong notes. If what was played fitted in with the larger scheme of things, that was OK. He went more for feel. That was the most important thing."

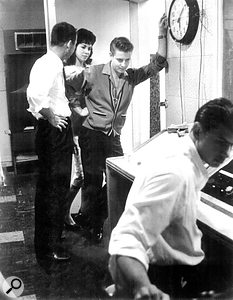

Levine in the control room at Gold Star in the late '50s with Eddie Cochran, his fianceé Sharon Sheeley and his manager, Jerry Capeheart.Photo: Ray Avery/Redferns

Levine in the control room at Gold Star in the late '50s with Eddie Cochran, his fianceé Sharon Sheeley and his manager, Jerry Capeheart.Photo: Ray Avery/Redferns

According to legend, 42 run-throughs took place over the course of four hours before Spector gave Levine the go-ahead to roll tape on 'Be My Baby', but this was fairly conventional for a man who used the studio as in instrument in itself.

"We almost never got into rolling tape before we got into overtime on a session," the engineer confirms, and this in turn raises the question as to whether the pursuit of excellence might have resulted in the musicians reaching a peak and then becoming frazzled.

"I often had a hunch that Phil needed that to happen," Levine says. "All of them were really great musicians, and what he didn't want was any individuality to show. They had to fit into the overall picture, whereas until they got tired enough they might be playing their hearts out. Now, I don't know if that's true or not, but it seemed that way."

The line-up changed from session to session, yet the layout within the live area usually remained the same. Looking out through the control room glass, Levine would see Blaine taking care of the main drum part and his fellow drummer playing figures right alongside him on the far-left side, while the keyboards were on the near-left side — grand piano, upright piano and electric piano, usually recorded with Electro-voice RE15s. The revolving door of percussionists was arranged along the back wall, and then to the far-right there was the horn section, miked with RCA 44s on the two trumpets and two trombones, as well as RE15s on the three saxophones. Centre-right were the woodwind players, while near-right were the bass guitarists, their amps each close-miked, often with Shure SM57s. Lastly, in the middle of the room, facing toward the drums, were the acoustic guitars, again mostly recorded with RE15s.

"I experimented a lot," Levine asserts. "I would go in and set up the studio, and then after the session I'd ask the guys if they could hear each other well and how it was working in there. According to their feedback, I might then try another setup the next time. Basically, I discovered things that didn't work and I found out why they didn't work — one thing I found out was that the drummers need to be placed up against the wall, otherwise they don't hear themselves and they play too loud trying to hear themselves. I think that's true with most instruments. If there's a wall behind them, the musicians can hear themselves.

"There were always more than 20 people jammed into that room when Phil was doing a session, but that wasn't the worst. The worst was when I worked with Herb Alpert on 'This Guy's In Love With You' and [pianist/co-composer] Burt Bacharach, who'd never been in the studio before, came in for the live recording with all the string players and couldn't believe what he saw. Of course, the piano was right at the back of the room, and he said he had to step over people to get there. That was the most crowded it ever got, but it was also crowded for Phil's stuff, and I found out that the more people you put in the room, the better the sound is. The bodies provide dampening."

Spector and Bono on the studio floor at Gold Star playing percussion.Photo: Ray Avery/Redferns

Spector and Bono on the studio floor at Gold Star playing percussion.Photo: Ray Avery/Redferns

Vocals

After the 'Be My Baby' rhythm track had been recorded within a day sans guide vocal, it was time for Ronnie Bennett to do her thing. In her 1990 autobiography (naturally titled after the song), the singer recalled that she and Spector had spent several weeks rehearsing the number prior to her flying out to Gold Star — she was the only Ronette on the session — and that it then took about three days to actually capture her performance.

"I was so shy that I'd do all my vocal rehearsals in the studio's ladies' room, because I loved the sound I got in there," she wrote. "People talk about how great the echo chamber was at Gold Star, but they never heard the sound in that ladies' room... That's where all the little 'whoa-ohs' and 'oh-oh-oh-ohs' you hear on my records

were born."

The following year, the liner notes of the album Presenting The Fabulous Ronettes Featuring Veronica included Levine's own recollection: "When I first met the Ronettes I didn't think they were going to be a very good group. Phil had said to me 'I found this group, they're good looking, but they don't sing too well.' So I said 'Well, why bother?' He said 'I kind of promised their mother.'"

Now Levine says: "We didn't have to work hard to get Ronnie's performance, but we had to work hard to satisfy Phil. He'd spend an inordinate amount of time working on each section and playing it back before moving on to the next one, and that was very hard for the singers. I always commiserated because Phil didn't pay too much attention to them. He treated them as if they were another instrument. I mean, they weren't ill-treated, they were just ignored."

Ronnie's memory of the 'Be My Baby' sessions corresponded with Levine's observation. Standing behind a big music stand, the future Mrs Spector would sing into a Neumann U47 and then, after completing a take, peer through the control room window in order to gauge the reactions of both producer and engineer.

"If they were looking down and fooling with the knobs, I'd know I had to do it again," she recalled. "But if I saw they were laughing and yelling 'All right!' or 'Damn, that little girl can really sing!' I'd know we had a take. Since my approach to each song was completely up to me, watching Phil and Larry react afterward was the only real feedback I ever got."

Spector At His Best: 'You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'

For Larry Levine, the zenith of Phil Spector's production career, and most perfect encapsulation of his Wall of Sound, was the Righteous Brothers' 'You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'. Written by Spector, Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, and recorded in November 1964, the track ran to 3:46, and when the producer refused to shorten it to appease radio DJs, he instead ensured that the running time printed on the label was '3:05'.

"The emotion on that recording ran the gamut," says Levine, who the following year won a Grammy for his engineering of Herb Alpert & the Tijuana Brass's A Taste Of Honey, before taking up with a heavily Spector-influenced genius in the form of Beach Boy Brian Wilson and engineering much of Pet Sounds and Smile. "Again, Phil took what was happening at the moment and totally changed the content, just as he'd done with 'Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah'. His biggest fear was that it was the only one of his songs that didn't have a backbeat. It was a real departure from anything else that he'd done, it had all of these emotional stop-starts and he wasn't sure that it was going to work. However, it was certainly the greatest record I ever worked on, and the reason I say that instead of 'River Deep, Mountain High' is that Phil kept reaching to go beyond where he had been previously. I think he got to that point before the technology was able to keep up with him on 'River Deep', whereas 'You've Lost That Lovin' Feelin'' achieved what he really wanted to hear.

"When 'River Deep' failed [in the US] he was really disappointed with the critics. Everyone wanted to see him fail, because he had this reputation for being stuck-up, and that isn't who he is when you get to know him. I love Phil. There's no doubt he's never been your run-of-the-mill type of guy, and I always admired him and his abilities, but unfortunately I think he kind of grew into what he was depicted as being."

Altogether Now!

Next on the agenda were the backing vocals, and according to Ronnie these were the most fun on the entire session, because everyone was invited to join in.

"If you were standing around and could carry a tune, you were a background singer in Phil's Wall of Sound," she wrote. "And everybody Phil knew seemed to show up the day we did backgrounds for 'Be My Baby'. Darlene Love was there, and we had Fanita James from the Blossoms, Bobby Sheen from Bob B. Soxx and the Blue Jeans, Nino Tempo, Sonny Bono — who was Phil's gofer in those days — and Sonny's girlfriend, who was a gawky teenager named Cher."

Gawky, perhaps, but her vocal traits were already in place. "We'd have to keep backing Cher up because her voice came through stronger than any of the others," Levine states.

Meanwhile, also of note is the fact that the 'Be My Baby' sessions represented the first occasion on which Phil Spector utilised a full orchestra string section at Gold Star.

"I love those strings, particularly at the end," Levine remarks. "They made me cry when I was mixing... I was always mixing for Phil's ears before we got to the final mix. You know, a lot of times when you've recorded something you can just sit back and play it for the producer, but that was never the case with Phil. When I played something back for him I also had to be mixing it, and that was a lot of work.

"Still, the final mix of the rhythm track, the strings and the voices was great fun, and I really approved of how we did it. Phil would leave the room and I would mix until I had something I liked, and then I'd call him back in and play it for him and he would critique it: 'The strings should come up here,' or 'They should come in there,' and then he'd leave again. I would mix according to those criteria, and when I had what I felt was good I'd call him in, we'd repeat the whole process, and what we'd achieve out of that was that I'd be able to mix without someone looking over my shoulder. I was mixing what I wanted to hear rather than what I thought somebody else wanted to hear, and then everytime Phil listened it would be with clean ears. That was a great way to mix."

The Wall Of Sound

Nevertheless, given the aforementioned mass line-up of musicians, was the Wall of Sound actually in the room when the track was being performed?

"Yeah, but you wouldn't have heard it if you walked in while we were recording it," comes the reply. "You see, whenever someone came into the control room, to impress them Phil would immediately raise the level of the monitors. Of course, we'd been listening for hours, so our ears would kind of re-tune to handle that, but I know that for people who came in at that level all they'd hear was a roar. That was until they were in there for a period of time. Then their ears would adjust and at that point they'd hear the Wall. For me, it was amazing to hear things from the outset, starting with the guitars and gradually building up to the Wall of Sound. That was a unique experience."