The 18-month gestation period behind Michael Jackson's Dangerous album and its lead single 'Black Or White' saw '80s studio perfectionism taken to extremes — and despite their success, the experience helped to convince co-writer, engineer and co-producer Bill Bottrell that there had to be another way to make records.

Grammy Award-winning producer, engineer, composer and musician Bill Bottrell has amassed some pretty amazing credits since leaving college in 1974 and first seeking work inside a recording studio. He's engineered the George Harrison/Bob Dylan/Roy Orbison/Tom Petty/Jeff Lynne opus The Traveling Wilburys, Vol. 1 (1988), Petty's Full Moon Fever (1989) and Madonna's Like A Prayer; co-produced Thomas Dolby's Aliens Ate My Buick album (1988), Madonna's songs on the Dick Tracy film soundtrack (1990) and a trio of numbers on Michael Jackson's Dangerous (1992); and produced the movie soundtrack to In Bed With Madonna (aka Truth Or Dare in the US, 1991), as well as Sheryl Crow's smash hit debut Tuesday Night Music Club (1993) and the eponymous I Am Shelby Lynne (2000). Most recently he has been performing live with various bands that he's assembled close to his studio near Mendocino in Northern California, while also running and maintaining said facility, and co-composing, producing, engineering and mixing Five For Fighting's second album, The Battle For Everything, released this year on the Sony Music label. Even when he was working on projects like Michael Jackson's Dangerous album, Bill Bottrell — shown here in the early '90s — was looking for ways to bring his country and roots influences to bear.

Even when he was working on projects like Michael Jackson's Dangerous album, Bill Bottrell — shown here in the early '90s — was looking for ways to bring his country and roots influences to bear.

Having worked as an engineer on the Jacksons' 1984 Victory album and then on Michael's Bad three years later as part of the second-tier team working at his Encino home, Bottrell received a call in 1988 to commence work on the follow-up. The fact that he was already a producer by then was quite timely, as the Gloved One was parting company with Quincy Jones and looking to create a more hard-edged, streetwise image with the help of some new writing/production/arrangement collaborators — most notably Teddy Riley, as well as Glen Ballard and Bruce Swedien. So it was that Bottrell ended up as a co-composer on 'Dangerous', 'Give In To Me' and 'Black Or White', while also co-producing the latter two in addition to the Jackson-penned 'Who Is It'.

From Bad To Worse...

"Michael told me at the end of the Bad sessions that he would hire me as a producer on his next album," Bottrell confirms, while explaining how his initial involvement with Dangerous commenced at LA's Oceanway complex.

"The genesis of the songs we co-wrote consisted of Michael humming melodies and grooves, and him then leaving the studio while I developed these ideas with a bunch of drum machines and samplers, including an Akai S1000," Bottrell says. "Still, we were only at Oceanway for a few weeks, and none of the things we worked on there actually made it onto the record."

Thereafter, the sessions moved to Westlake, where Bruce Swedien utilised one room, Bottrell used another and, eventually, drummer/percussionist/synth player Bryan Loren worked in a third. Armed with a Neve console, Bottrell used a pair of 24-track Studer analogue tape machines to record initial tracks and then compiled things on Mitsubishi 32-track.

"As soon as we got to Westlake, the first thing that Michael hummed to me was 'Black Or White'," he recalls. "He sang me the main riff without specifying what instrument it would be played on. I just hooked up a Kramer American guitar to a Mesa Boogie amp, miked it with a Beyer M160, and got that gritty sound as I played to his singing. He also sang me the rhythm and I put down a simple drum-machine pattern coming out of an Emulator, and he then left so that I could spend a couple of days working alone on the track. It was Michael who actually drew me out as a musician — on the Bad sessions he would hum me things and go away, and I'd be there alone for two weeks, working on a track. I was used to sampling, but he needed music; guitars, keyboards, you name it. That's what he expected of me. He assumed I could do it, and since I had been a musician before going into engineering I just followed his lead.

"For 'Black Or White' I laid down a more precise guitar part, and I also had this very dorky EIII drum machine playing a one-bar loop. Back then I would use a Hybrid Arts sequencer that I loved dearly — it ran on the Atari platform and was kind of sophisticated for its time, and I would use that for all my MIDI storage. I could run anything through it, so I set about adding loads of percussion, including cowbells and shakers, trying to get a swingy sort of groove. You see, the guitar swung a lot, as defined by the original hook that Michael had sung to me, and the percussion devices were pretty straightforward, but the groove itself was heavily tweaked in the sequencer in order to be complex and non-linear. This basically amounted to shifting things and manipulating the data.

"As soon as I sorted out the guitar and drum machine parts on day one, Michael performed a scratch vocal as well as some BVs. I miked him with a [Neumann] U47, which was my choice, and I'd take out most of the bottom end and compress the rest with my Sontec limiter. The guy's an absolute natural — I mean, we're talking about Michael Jackson — and for me the best thing about 'Black Or White' was that his scratch vocal remained untouched throughout the next year [of work on Dangerous] and ended up being used on the finished song. He had some lyrical ideas when he first entered the studio, and he filled them out as he went along."

Keeping It Loose

So it was that, within two days of commencing work on 'Black Or White' at Westlake, Bottrell had recorded the guitar, drum loop, a small amount of percussion and what would prove to be the finished vocal. Aware that the addition of just bass and a little more percussion would be sufficient to flesh out the verses and choruses, he subsequently took it upon himself to ensure that Jackson would allow the song to retain a basic, more free-and-easy sound.

So it was that, within two days of commencing work on 'Black Or White' at Westlake, Bottrell had recorded the guitar, drum loop, a small amount of percussion and what would prove to be the finished vocal. Aware that the addition of just bass and a little more percussion would be sufficient to flesh out the verses and choruses, he subsequently took it upon himself to ensure that Jackson would allow the song to retain a basic, more free-and-easy sound.

"I thought the vocal was brilliant, and that the loose, imperfectly layered backgrounds were perfectly charming," Bottrell says. "As opposed to some of the other people who worked with Michael at the time, when I was allowed to produce I would consistently try to go for simpler vocals, comping them from two or three takes, with looser backgrounds and a more instinctive feel. In this case, he came in with such an endearing lead vocal and background track, I really resolved to try and keep it. Of course, it had to please him or he would have never let me get away with that, but the way it went down is that we had the verses and choruses — the main part of the song — and there were two big gaps in the middle which prompted us to look at each other and say 'Well, we'll put something in there.' They were big gaps.

"The total length of the song up to that point was probably about a minute and a half, and Michael has always felt better really fleshing out something over a long period of time to discover everything that he can about it. Most Michael Jackson songs are worked on quite heavily, for months and months, and we certainly had those months when we worked on 'Black Or White' along with the other songs. However, we worked on the middle sections, filling in those two big gaps, and this meant that, while the song got the amount of attention that Michael was used to giving something, I was able to retain its strange, funky, loose and open Southern rock feel all the way through to the end. We never touched anything else. I mean, he never asked to redo the vocals, and so while I say it was my agenda to keep things as they were, maybe it was his as well.

"In fact, on 'Give In To Me' he looked to me for those looser, more instinctive vocals. These contrasted with what was achieved by the other people he was working with, because in that case he had the same agenda as I had. Still, we took that song too far. We had a live take of me sitting on a stool, playing guitar, and him singing, with a very simple drum loop running throughout. Michael loved that, but it was me who got insecure and started layering things. Eventually, he had Slash come in and add loads of guitars, and the song was transformed; not for the better, in my view. And that had nothing to do with Slash, but by virtue of the production that went into it.

"As a co-producer, Michael was always prepared to listen and put his trust in me, but he was also a sort of guide all the time. He knew why I was there and, among all the songs he was recording, what he needed from me. I was an influence that he didn't otherwise have. I was the rock guy and also the country guy, which nobody else was. He has precise musical instincts. He has an entire record in his head and he tries to make people deliver it to him. Sometimes those people surprise him and augment what he hears, but really his job is to extract from musicians and producers and engineers what he hears when he wakes up in the morning.

"After the first couple of days working on 'Black Or White', I put down this big, slamming, old sort of rock & roll acoustic guitar part using my all-mahogany 1940s Gibson LG2. It's very rare and pretty battered, and it's actually a deeper acoustic than most other Gibsons — you can hit it hard and it doesn't cave in. The part I played was in the style of some of my own musical influences, like Gene Vincent, where you just hit the guitar hard and play a big open 'E' and an 'A' chord. I was quite pleased with it and wondered if Michael was going to like it, but he didn't say a thing. He just accepted it when he first heard it, and I was really happy to get that type of classic sound on a Michael Jackson album."

Taking The Rap

Brad Butler assisted Bill Bottrell in terms of tweaking the percussion and getting it to swing in a complex way — mechanically, but with a human feel. At this point they were in Westlake's Studio B while Bruce Swedien utilised the Harrison-equipped Studio A. But then, while attention turned towards some other numbers — 'Earth Song', which would end up on 1995's HIStory collection, and a couple that are still on the shelf — Bottrell switched to Studio A and remained there for about six months before relocating to Ocean Way's Record One complex in Sherman Oaks. It was there that he and Michael Jackson set about filling those two big gaps in the middle of 'Black Or White'. Initially only featuring a drum machine, these would eventually comprise the song's 'heavy metal' section and another that would evolve into the rap. In all, this intermittent process took about a year, during which time several more tracks were also recorded.

The live area at Westlake Studio A, which Bill Bottrell made a point of using to track vocals and other instruments.

The live area at Westlake Studio A, which Bill Bottrell made a point of using to track vocals and other instruments.

"I had hopes to insert a rap in the first eight and Michael came up with the idea of putting heavy metal guitars in the second eight," Bottrell states. "He sang me that riff and I hired my friend Tim Pierce, because I couldn't play that kind of guitar. Tim laid down some beautiful tracks with a Les Paul and a big Marshall, playing the chords that Michael had hummed to me — that's a pretty unusual approach. People will hire a guitar player and say 'Well, here's the chord. I want it to sound kinda like this,' and the guitarist will have to come up with the part. However, Michael hums every rhythm and note or chord, and he can do that so well. He describes the sound that the record will have by singing it to you... and we're talking about heavy metal guitars here!"

After Tim Pierce had adhered to the main man's wishes, Michael Boddicker played a stand-alone Roland sequencer part that was meant to sound like high-speed guitar segueing into and out of the heavy metal section. Bottrell's young musican friend, Kevin Gilbert, also contributed some high-speed sequencer.

"Michael Boddicker played synths and keyboards on several songs," Bottrell recalls, "and on 'Black Or White' he played really fast sequencer notes running up and down, and I recorded his MIDI out of that box into my Hybrid Arts. I then used that, put a guitar sample in my Akai and ran it through the Mesa Boogie amp in order to make it sound more like a guitar. At that point the heavy metal section was intact and Michael [Jackson] sang it, which meant we only had the rap to do. Things remained that way for quite a time, during which I put Bryan Loren on Moog bass and tried Terry Jackson on five-string electric bass going through a preamp that I had built. Bryan's Moog part was really good, and I used some of Terry's notes to fortify it and make a rhythm, while also replacing the simple Emulator drum machine with live drum samples that I had in my Akai.

"All the time I kept telling Michael that we had to have a rap, and he brought in rappers like LL Cool J and the Notorious BIG who were performing on other songs. Somehow, I didn't have access to them for 'Black Or White', and it was getting later and later and I wanted the song to be done. So, one day I wrote the rap — I woke up in the morning and, before my first cup of coffee, I began writing down what I was hearing, because the song had been in my head for about eight months by that time and it was an obssession to try and fill that last gap."

"All the time I kept telling Michael that we had to have a rap, and he brought in rappers like LL Cool J and the Notorious BIG who were performing on other songs. Somehow, I didn't have access to them for 'Black Or White', and it was getting later and later and I wanted the song to be done. So, one day I wrote the rap — I woke up in the morning and, before my first cup of coffee, I began writing down what I was hearing, because the song had been in my head for about eight months by that time and it was an obssession to try and fill that last gap."

It is interesting that Jackson left this task to Bottrell and didn't try to fill said gap himself. "That's the sort of thing he does," asserts Bottrell. "It seems kind of random, but it's as if he makes things happen through omission. There's nobody else, and it's as if he knows that's what you're up against and challenges you to do it. For my part, I didn't think much of white rap, so I brought in Bryan Loren to rap my words and he did change some of the rhythms, but he was not comfortable being a rapper. As a result, I performed it the same day after Bryan left, did several versions, fixed one, played it for Michael the next day and he went 'Ohhh, I love it Bill, I love it. That should be the one.' I kept saying 'No, we've got to get a real rapper,' but as soon as he heard my performance he was committed to it and wouldn't consider using anybody else."

The Notorious W Cool B? If the hat fits... "I was OK with it," he says. "I couldn't really tell if it sounded good, but after the record came out I did get the impression that people accepted it as a viable rap. Since I try to do everything in the spirit of instinct and in-the-moment, I had given it my best shot, and apparently it worked... I also played a funky guitar part on my Kramer American in the rap section, but then I still felt that the song needed some sort of fire, and so I sampled distorted guitar riffs into my Akai and laid them down all over the place. It just need a more live feel, and a real guitar would have had the wrong effect, so I laid out a keyboard of maybe eight guitar versions, and as I didn't want to do it — I had heard the song so many times — I brought in my friend Jasun Martz. He listened once to the samples, listened to the song and just laid them down using my Hybrid Arts, a MIDI keyboard and the Akai sampler, and it worked great. He brought an immediacy and a rock & roll fire to something that had been pieced together."

Wasting Space

As a response to the claustrophobic recording enviroments he encountered on projects like the Dangerous album, Bill Bottrell established a one-room studio called Toad Hall, where the emphasis would be on capturing the feeling of live performances.Photo: Bill Bottrell

As a response to the claustrophobic recording enviroments he encountered on projects like the Dangerous album, Bill Bottrell established a one-room studio called Toad Hall, where the emphasis would be on capturing the feeling of live performances.Photo: Bill Bottrell

One way in which Bill Bottrell swam against the tide when working on 'Black Or White' was in actually using the live rooms in Westlake and Record One studios; his own guitar parts were tracked in the control rooms, but almost all the other elements, including Michael Jackson's vocals, were tracked in the studio live areas. "Don't forget, this was the late '80s, when so much work was being done in control rooms and these huge studios were being wasted," Bottrell remarks. "I always found it ludicrous the way studios were designed — all the gear would be in the control room and there'd be no space for people — so I built my own studio consisting of one room with no glass in between."

Named Toad Hall and located within a storefront venue near to the Pasadena Playhouse a few miles north-east of Los Angeles, this comprised a long, faux-stone, high-ceilinged room with neo-Gothic lighting, book-lined and tapestry-draped walls, antique furniture and plenty of classic recording gear. It was here that, among numerous other projects, Bottrell produced, engineered and co-wrote Sheryl Crow's Tuesday Night Music Club album, and since relocating to a tiny, remote Northern California village during the second half of the 1990s he has pretty much replicated the unique look and atmosphere with the expansive, open-plan Williams Place, which houses a Neve 8058 console, Pro Tools, and Radar II and Studer A800 recorders.

Mixing & Matching

Conforming to his usual approach, Bottrell basically mixed and built the track as he went along. "Even back then I didn't believe in 'mixing' per se. I mix as I go, and when the song is finished recording I leave the faders where they are and press Record on the machine."

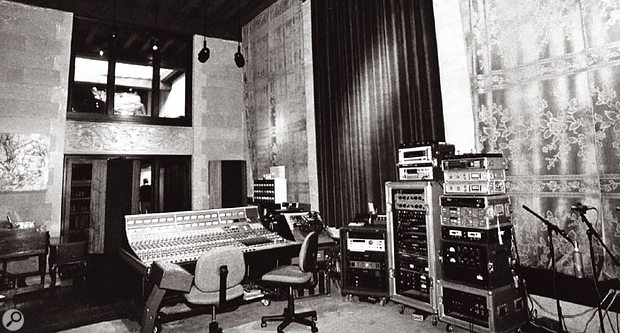

The control room at Record One as it appeared in 1991, housing this Neve desk.

The control room at Record One as it appeared in 1991, housing this Neve desk.

Still, this didn't mean that everything was simple and straightforward when the mix proper took place on Record One's Neve 8078. How could it be? "Mixing was quite a trip," he confirms. "I was dealing with the fine points of audio and equipment and what they were doing to the feel of the song. That's where I struggled. It was down to balances or effects. There weren't many effects. As I've said, the main part of 'Black Or White' always remained the same, but I could not get the rap section and heavy metal part to sound right. I therefore went over to Larrabee, where the bulk of the company had moved, and did a mix over there and then couldn't get the country part to sound right. The problem was the SSL, which really worked for the heavy metal section — where the Neve produced too much ringing — but was too cold and clinical for the rootsy and nostalgic country part. It didn't work at all, so I cut the two together, using a Neve for the main parts and the SSL for the rap and heavy metal sections.

"It didn't take a long time to get that together, but it did take a long time for me to realise that's what I had to do. I was going around in circles for a while, and although Michael would drop in every now and then he wasn't aware of the struggles that I was going through. I don't think I ever told him. I would try something, it would be time to finish the song and turn it in, so I'd do the mix and the next day I'd hear it and not like it for some reason. Nevertheless, each time I did a mix it would only take an hour or two, or less, because by then the song was so commodified in my mind and repeated so many times that there was nothing to mix. I was just trying to get the audio to sound right."

A Musical Education

In all, the Dangerous project accounted for about 18 months of Bill Bottrell's life, and working on it brought him into direct contact with the overblown megastar ethic at its most extreme. This, in turn, was an education for him, both in terms of conforming to this type of sensibility and in concluding that in future he'd rather work on rootsier, more understated, less commercially obsessed projects — ones that would connect with his own Appalachian and country leanings.

Bill Bottrell today."By then I was at the end of my musical education with Michael," he says. "I had been out at his house for a couple of years and at various studios with him before that, so it was all adding up, and by the time we even started the Dangerous album I was well into that system. It taught me a lot about really going all the way for something, working and working until there's some kind of perfection. Objectivity is everybody's biggest problem, especially if you've worked a long time on a song, but there's also a threshold beyond which that isn't a problem any more because, having the luxury of so much time to spend, your failures in objectivity eventually get fixed.

Bill Bottrell today."By then I was at the end of my musical education with Michael," he says. "I had been out at his house for a couple of years and at various studios with him before that, so it was all adding up, and by the time we even started the Dangerous album I was well into that system. It taught me a lot about really going all the way for something, working and working until there's some kind of perfection. Objectivity is everybody's biggest problem, especially if you've worked a long time on a song, but there's also a threshold beyond which that isn't a problem any more because, having the luxury of so much time to spend, your failures in objectivity eventually get fixed.

"In other words, if something ends up sounding wrong, there's no deadline to turn it in. And you will hear that it's wrong if you get away from it for five days and then hear it again. You always have that second chance, as well as that third or fourth or fifth chance, and that's a technique which I learned from Michael, in addition to meeting the challenge of outdoing whatever's out there within the same game. It's a case of doing whatever it takes. So, I learned all of those things... and never did them again. I totally refused to, but that doesn't mean I disrespected doing them. I absolutely respected doing them. It just taught me that there is another way to beat everybody, maybe by taking the exact opposite approach to a technique that requires a tremendous amount of time, listening to what records are doing, listening to what gimmicks people are using and making sure you did it better.

"What I decided to try was to not listen to anybody else, but go to the extremely raw and take that to its logical ends. Only serve the words and the melody and the singer, and although that can take you to some extreme place, you won't feel it's extreme because you haven't been listening to everybody else. This is the approach I've been taking ever since, and while it may be less contrived by definition, I say that without imposing any judgement on contrivance. At the time, I was interested in the techniques employed for a project like Dangerous. It was a challenge to me, and none more so than ensuring that 'Black Or White', with its cool Southern rock/country thing happening, didn't go in the wrong direction. That was my agenda: to save take one."