This month, Sound On Sound begins a major new series, looking back in detail at the engineering and production behind some of the most historically significant recordings ever made, with the story of the first and greatest British rock & roll record.

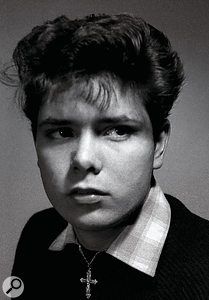

A youthful Cliff Richard poses for the cameras.Photo: Beverley Lebarrow / RedfernsAs a staff engineer at the EMI Studios on Abbey Road in North London from 1958 to 1968, Malcolm Addey was the main man behind the console for artists ranging from Cliff Richard, the Shadows and Helen Shapiro to John Barry and Adam Faith. Thereafter, having overdosed on middle-of-the-road pop projects, Addey was lured away to New York City by Dave Teig at Bell Sound where, in addition to his mainstream assignments, his horizons were also broadened by a body of work that ranged from radio and TV commercials to jazz and rhythm & blues.

A youthful Cliff Richard poses for the cameras.Photo: Beverley Lebarrow / RedfernsAs a staff engineer at the EMI Studios on Abbey Road in North London from 1958 to 1968, Malcolm Addey was the main man behind the console for artists ranging from Cliff Richard, the Shadows and Helen Shapiro to John Barry and Adam Faith. Thereafter, having overdosed on middle-of-the-road pop projects, Addey was lured away to New York City by Dave Teig at Bell Sound where, in addition to his mainstream assignments, his horizons were also broadened by a body of work that ranged from radio and TV commercials to jazz and rhythm & blues.

Now freelance for more than three decades, Malcolm Addey includes projects by Chick Corea, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Roberta Flack, Judy Garland, Lionel Hampton, John Lee Hooker, Liza Minnelli, Junior Parker, Buddy Rich, Diana Ross and Mel Tormé among his formidable list of recording, mixing and mastering credits. Yet he is also justifiably proud of the fact that he engineered all of Cliff Richard's recordings through 1966, commencing with a session that took place inside EMI's Studio Two on the evening of Thursday, July 24, 1958, which gave rise to what is widely acknowledged to be the first true all-British rock & roll record, and the only pre-Beatles UK number to have been inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

Standing In

Since being hired as an assistant back on March 10 of that year, Addey had worked on some audition tests, a few pop recordings and even a couple of jazz projects with George Martin before receiving the call to help out on a 7pm to 9pm session for a 17-year-old newcomer named Cliff Richard. Veteran producer Norrie Paramor would be in charge of the proceedings, while the mixing console was scheduled to be operated by Peter Bown. Along with Stuart Eltham, Bown was one of the studio's only engineers then specialising in pop, yet on this particular night he had tickets to see an opera production in Covent Garden, and so, for the debut of an unknown rock artist, he suggested that Addey could take over.

Malcolm Addey operating the EMI eight-input mono console inside Studio Two, circa 1958/59.Photo: Malcolm Addey"Not having worked with me before, Norrie was understandably a little nervous, and so he asked Peter to stay behind a little while and make sure that everything was OK," Addey recalls. "Beforehand, Peter and I sat down for about 15 or 20 minutes to make a plan, as we always did, and he said, 'It's your session, Malcolm. Do it your way.' So that's what I did, although I didn't stray all that far from the norm because it would have been dangerous to do that. We basically drew a diagram depicting what mics we wanted where, and two crews of people would see this sheet: the attendants who cleaned the studios, pushed the chairs around, and positioned the carpets and acoustic screens, and the electronic maintenance engineers who actually set up the mics."

Malcolm Addey operating the EMI eight-input mono console inside Studio Two, circa 1958/59.Photo: Malcolm Addey"Not having worked with me before, Norrie was understandably a little nervous, and so he asked Peter to stay behind a little while and make sure that everything was OK," Addey recalls. "Beforehand, Peter and I sat down for about 15 or 20 minutes to make a plan, as we always did, and he said, 'It's your session, Malcolm. Do it your way.' So that's what I did, although I didn't stray all that far from the norm because it would have been dangerous to do that. We basically drew a diagram depicting what mics we wanted where, and two crews of people would see this sheet: the attendants who cleaned the studios, pushed the chairs around, and positioned the carpets and acoustic screens, and the electronic maintenance engineers who actually set up the mics."

Although Cliff Richard's name would soon become synonymous with that of his backing group, the Shadows, the band members initially called themselves the Drifters, before it was pointed out that there was already a far more famous, well-established outfit utilising that moniker in the US. For Cliff's very first session, his band basically consisted of British Drifters Ian Samwell on rhythm guitar and Terry Smart on drums, supplemented by session musicians Ernie Shear on lead guitar and Frank Clarke on upright bass. While Malcolm Addey is certain that Cliff was miked with a Neumann U47, 45 years later he can only provide an amalgam of the other microphones that he typically would have used: a U47 or STC 4033 on each of the electric guitars; a U47, 4033 or AKG C12 on the string bass; and an RCA 44BX, Neumann KM56 or Altec 21B overhead on the drums.

"At that time I would have positioned the mic about six to 12 inches away from the F hole, which is a greater distance than we would use today," Addey explains. "We'd do that to be cautious. The overhead on the drums would be about six feet off the floor above the kit, which in those days consisted of a snare drum and bass drum, and we didn't use a bass drum mic. For the guitars, I placed the microphones extremely close to the speakers, and that was perhaps a little innovative because the other engineers weren't doing that back then."

In addition, the Mike Sammes Singers, a vocal group comprising four men and four women, sang backup on the first song recorded that night, 'Schoolboy Crush', while standing on either side of a C12 or Neumann U48 in figure-of-eight — the null area was directed towards the drums for better isolation. Adhering to the then-standard procedure of covering an American hit — in this case, a sophomoric mid-tempo number originally recorded by Bobby Helms — the song was originally designated as the 'A' side of Cliff's first single.

"Norrie Paramor thought that the other song, 'Move It!', was rubbish," Addey recalls. "At that point, none of us knew one end of a rock & roll record from the other."

Two Steps Forward

While Studio One catered almost exclusively to orchestral recordings and Studio Three had been designed specifically for chamber music, Studio Two was the facility's pop domain. The upstairs control room housed an EMI RS1 mono desk with two-band, Pultec-type peaking EQ on each of its eight inputs — as opposed to the classically oriented shelving EQ that was to be found in the other studios — at 5kHz and 100Hz. There was also an echo send for all of the inputs, echo return, a peak level meter and a single main gain control. The monitor speaker, positioned to the left of the console, was a Tannoy 15-inch dual-concentric mounted inside a large bass reflex enclosure and driven by the power amp built into an EMI BTR2 mono tape machine. Running at 15ips, this served as the main recorder while another BTR2 stood by in case there was a need to do mono-to-mono overdubs.

Inside Studio Two, circa 1961: (top row, left to right) guitarist Bruce Welch, drummer Brian Bennett, Cliff Richard, bassist Licorice Locking, Shadows manager Peter Gormley. Cropped, at far right, is producer Norrie Paramor. Malcolm Addey (talking to Brian Bennett) sits at the EMI REDD 17 console, next to guitarist Hank Marvin (with back to camera).Photo: EMI Archives

Inside Studio Two, circa 1961: (top row, left to right) guitarist Bruce Welch, drummer Brian Bennett, Cliff Richard, bassist Licorice Locking, Shadows manager Peter Gormley. Cropped, at far right, is producer Norrie Paramor. Malcolm Addey (talking to Brian Bennett) sits at the EMI REDD 17 console, next to guitarist Hank Marvin (with back to camera).Photo: EMI Archives

Meanwhile, a third machine running at 30ips took care of the delay going into the echo chamber. This was an L-shaped room located behind the north wall of the studio, with brick walls, reinforced concrete ceiling and floor, and a half-dozen glazed ceramic drainpipes that stood vertically and were positioned around the chamber to help scatter the sound. A Neumann KM53 omnidirectional mic was placed at one end of the room, while at the other end, pointing slightly upwards and towards a corner, there was a Tannoy 15-inch dual-concentric speaker driven by a Leak TL25 amp.

"Having paid close attention to what I'd seen Peter Bown and Stuart Eltham do in other sessions, I followed common practice while adding some modifications of my own," says Addey. "Not that there'd been all that many examples of common practice at EMI with a rock & roll group. Therefore, I suppose what I brought to the recordings was the way in which I mixed them.

"A few bars into 'Schoolboy Crush', Peter decided that I didn't need his help, and so he left for the opera and we completed the song in two or three takes. I can remember Norrie grinning all over his face due to the way I was riding the gain — or potting the gain, as we called it then — between the lead vocal and the group, because there was a lot of call and response. He thought that was kind of cool, but I guess that was just me starting to do my thing. I was new blood and I was only a few years older than Cliff, whereas all of the other engineers were old enough to be his father. Perhaps thanks to my youth, I wasn't very concerned about keeping the needle just under the red, and to this day that's still my attitude. If something goes over but it sounds good, leave it that way. That becomes part of the record.

Diagram of the Studio Two layout for the 'Schoolboy Crush'/'Move It' session — the vocal group wasn't there for the latter recording. Photo: Malcolm Addey

Diagram of the Studio Two layout for the 'Schoolboy Crush'/'Move It' session — the vocal group wasn't there for the latter recording. Photo: Malcolm Addey

"From the start of my career there was never anyone looking over my shoulder. Pop records were not made that way. Whatever restrictions we had to deal with weren't imposed by a person but by the laws of physics. I mean, if there were a hundred grooves per inch on an LP, we might reduce that to 80 on a single in order to get more volume, whereas if someone squeezed 30 minutes onto one side of a record there would be absolutely no punch when you played it. Then again, tape was very forgiving. You could probably go to +10 if the tape was good and the machine was properly aligned, but tape starts to saturate at a certain point and you get a sort of limiting effect; not amplitude limiting, but frequency-selective limiting, so some things will limit more than others and produce a very unpleasant sound. The limitations weren't 'downstairs' in the studio, but 'upstairs' where the sound was inscribed into the acetate. If you recorded something with excessive amplitude and velocity, no pickup on this earth could track it, and the cutting engineers would have to use their special skills to get around this.

"On that first session with Cliff, Norrie loved the sound that was coming out of the speaker, and that was good enough for him. For his part, Cliff was a nice kid and, as time would prove, he was also one of the nicest people I could have ever hoped to work with. He was always open to suggestions, I never saw him get heavy and he had this absolutely wonderful recording voice, the type that we dreamed of when listening to American records. There was no need to load it up with all kinds of EQ to make it jump out from the background. It had a big, full, fat sound on the U47, and yet you could still hear everything else that was going on. During the past 20 years or so I've been disappointed to hear it sounding way, way thinner due to all of the effects being employed. They EQ things out of existence now, whereas back then everything was straight to mono with nothing in between. The record simply consisted of whatever was on the tape."

Movin' On Up

Ian Samwell, who wrote and played guitar on 'Move It!'. Photo: Rick Richards / Redferns

Ian Samwell, who wrote and played guitar on 'Move It!'. Photo: Rick Richards / Redferns

What was on this particular tape was initially perceived as just a throwaway 'B' side. Ian Samwell had written 'Move It!' aboard a bus while travelling just a few miles from his home in London Colney, Hertfordshire, to Cliff's place in neighbouring Cheshunt. Consisting of just three chords, the song was quickly demonstrated to the other musicians who remained in Studio Two once the Mike Sammes Singers had departed following the completion of 'Schoolboy Crush'. Samwell also scribbled out the lyrics and placed them on Ernie Shear's music stand so that he would know where to place the guitar fills. Shear subsequently played the song's soon-to-be-famous intro as well as the first two bars of rhythm on his Hofner President, before taking care of the fills while Samwell played rhythm.

"Ernie played an absolutely wonderful introduction," confirms Malcolm Addey. "He was one of those guys who would play whatever was required without getting uptight, and so he just turned up his EQ and let it rip. It came out really great, and that's what got everybody's attention. For his part, Cliff liked to play while he was singing, so Norrie allowed him to hold onto his guitar, and after a false start we completed the song in a couple of takes. There were no edits whatsoever — we did very few edits in the pop field, and those were usually only on an LP, which might be a little more complex.

"I didn't have a reference point for this kind of work. It was something very new, and had, say, a BBC engineer — with stricter transmitter limitations — taken care of the recording, it certainly would have sounded much tamer. I was able to go beyond certain parameters, allowing the needle to go into the red and also EQing certain things to help brighten them up. I've never been a great lover of the post-session EQing and messing around that many people rely on these days. I like to get it right at the time, and I suppose instinctively I was doing that for 'Move It!'. I wanted the record to sound the same as that which I heard coming out of the speaker in the studio, and I'm glad to say that it still does!"

The American Sound

"EMI's A&R department at Manchester Square used to send us piles of 45 singles from the States, mostly from labels we'd never heard of, and whenever we had some spare time Peter Bown, Stuart Eltham and I would get the turntable out and play them," recalls Malcolm Addey. "As we listened, we would each hear different things of course, but we'd discuss how much of what we heard was in the studio and how much was due to the musicians, which in America was about 95 percent of the overall equation anyway. For example, although Columbia Records in the US was a large, conservative company like EMI, it was also releasing a lot of material from small studios in provincial towns around the States by people who made records just any way they could, without any regard for technical standards. However, they were also capable of cutting the hottest records in terms of level, and ours seemed so tame by comparison.

"That was due to a restriction not 'downstairs' in the studio, but 'upstairs' in the mastering room, because we didn't have the equipment capable of cutting such levels. Malcolm Davies, who was one of the brighter cutting engineers, got around this problem in all kinds of different ways, but he had arguments with the chief engineer Bill Livy, who was very involved in setting EMI Studios' technical standards. At one point I told Malcolm, 'These cutting amplifiers are about a tenth of the power they should be,' and when I later moved to the States I learned that what I had said was quite true. We'd been using modified Leak TL12 amplifiers, which were high-quality push-pull valve amps used by hi-fi enthusiasts, and which didn't provide nearly enough power to drive a cutting head. I mean, I'd had a disc cutter when I was a teenager — I had cut 78s as a hobby — and so I knew that you had to have a hefty amplifier. I'd read all the books, most of which came from America, and they'd talk about these 100 Watt amplifiers which we should have been using.

"The fact that the Americans used those amps gave them a distinct edge, because they could go to high levels without distortion. What's more, the likes of Columbia, Bell Sound and various American independents were not following the standards in terms of the depth of a record's grooves — they'd cut them much deeper so that the playback stylus would ride the grooves better on hot levels and bass notes. They were doing this to get the loudest possible sound out of jukeboxes, whereas if Malcolm Davies had broken a rule like that, the factory would have rejected the record and he would have been for the high jump. Still, even though it was obvious to me that EMI was way behind in this regard, my attitude was to just get in there and do it. I had the greatest admiration for Peter and Stuart, but there may have been an inherent tradition that held them back. I, on the other hand, really didn't give a damn what the people 'upstairs' might say about my tape being over the top. All they had to do was bring the level down, and what I did wouldn't affect them one way or another unless I went really crazy."

A Step On The Ladder

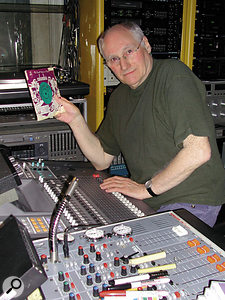

Malcolm Addey today in his home studio, holding his own copy of 'Move It!' which was among the batch of the first 10,000 copies pressed back in 1958.Photo: Charlotte SchroederIt didn't take long for 'Schoolboy Crush' to get relegated to the B-side: when TV producer Jack Good heard 'Move It!', with its distinctive guitar riff and an Americanised lead vocal that was light years away from the often staid British style, he practically flipped. Thanks to Good's heavy promotion of the song, and Cliff's debut on his show Oh Boy!, 'Move It!' climbed rapidly up the UK charts following its release on August 29, 1958, peaking at number 2 in early November and establishing a new benchmark for homegrown rock material. It was the beginning of a successful career as a songwriter and, later, producer for Ian Samwell, who sadly died on March 13 this year at the age of 66. As for Malcolm Addey, he was, for now, the new boy wonder at the EMI Studios on Abbey Road, and thus commenced not only a successful career behind the console for him and in front of it for Cliff Richard and the Shadows, but also a fruitful relationship between all involved.

Malcolm Addey today in his home studio, holding his own copy of 'Move It!' which was among the batch of the first 10,000 copies pressed back in 1958.Photo: Charlotte SchroederIt didn't take long for 'Schoolboy Crush' to get relegated to the B-side: when TV producer Jack Good heard 'Move It!', with its distinctive guitar riff and an Americanised lead vocal that was light years away from the often staid British style, he practically flipped. Thanks to Good's heavy promotion of the song, and Cliff's debut on his show Oh Boy!, 'Move It!' climbed rapidly up the UK charts following its release on August 29, 1958, peaking at number 2 in early November and establishing a new benchmark for homegrown rock material. It was the beginning of a successful career as a songwriter and, later, producer for Ian Samwell, who sadly died on March 13 this year at the age of 66. As for Malcolm Addey, he was, for now, the new boy wonder at the EMI Studios on Abbey Road, and thus commenced not only a successful career behind the console for him and in front of it for Cliff Richard and the Shadows, but also a fruitful relationship between all involved.

"Even listening to that record today, there's nothing that I would do differently," Addey says. "As is the case with so many classic tracks, you probably couldn't have repeated it like that. 'Move It!' signalled a departure from the formality of recording; not a violent one, not an extreme one, but the first step on the ladder towards a whole new wave of British recordings."