Half a century in the business has seen recording engineer Al Schmitt reach the very top of his profession, but even a man of his experience can find himself faced with new challenges. So it was in 1991, when he was called upon to turn a classic Nat 'King' Cole recording into a duet with Cole's daughter Natalie...

A legend on the studio scene and a perennial at the Grammys, where he has won a dozen awards as Best Engineer, Al Schmitt has recorded and mixed no fewer than 150 gold and platinum albums during a career that commenced back in the early '50s. In 1997, he was an inductee into the Technical Excellence & Creativity Awards Hall Of Fame.

One of Schmitt's earliest sessions was with Duke Ellington, and since then, via stints at Apex Studios, Atlantic and Prestige in New York City, as well as at Radio Recorders and RCA in Hollywood prior to going independent in 1966, the artists with whom he's been involved have run the gamut of popular music. These include jazz greats like Chet Baker, Gerry Mulligan and Thelonius Monk; vocalists such as Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Ray Charles, Sam Cooke, Connie Francis, Eddie Fisher, Rosemary Clooney and Sammy Davis Jr; composer/orchestrators Henry Mancini and Quincy Jones; artists such as Toni Braxton, Anita Baker, George Benson, Luther Vandross, Vanessa Williams, Dave Grusin, Diane Schuur and Al Jarreau; and rock icons like Elvis Presley, Ike & Tina Turner, Jefferson Airplane, Hot Tuna, Steely Dan, Madonna and Michael Jackson.

Recently, Al recorded Bruce Willis singing for the Rugrats Go Wild film soundtrack and mixed a Lee Ann Rimes Christmas record, and in early May he commenced work on a Barbra Streisand album of movie songs at the Sony scoring stage in Culver City, a place that he describes as "one of the most beautiful-sounding rooms on the planet, along with Abbey Road and AIR studios". Thereafter, in the first half of June, he segued to a project with Diana Krall, justifying his assertion that "my plate is pretty full, and I'm really lucky because I get to work with the best people and a lot of interesting people".

Al Schmitt with Natalie Cole during the recording of 'Unforgettable'.The first of Al's Grammy Awards was for Henry Mancini's Hatari! film score in 1962; his most recent was for Diana Krall's 2002 The Look Of Love and Live In Paris albums. Between the two came a similar award for his work on Natalie Cole's Unforgettable album in 1991, including the title track that paired her vocal with that of her late father, recorded at the Capitol Studios in Hollywood exactly 40 years earlier.

Al Schmitt with Natalie Cole during the recording of 'Unforgettable'.The first of Al's Grammy Awards was for Henry Mancini's Hatari! film score in 1962; his most recent was for Diana Krall's 2002 The Look Of Love and Live In Paris albums. Between the two came a similar award for his work on Natalie Cole's Unforgettable album in 1991, including the title track that paired her vocal with that of her late father, recorded at the Capitol Studios in Hollywood exactly 40 years earlier.

Reaching The Summit

While Tommy LiPuma and Natalie Cole were the album's executive producers, LiPuma, André Fischer and David Foster shared the production chores. Al Schmitt had collaborated with all three men on a number of projects, and so it was natural that he was called upon to record some of the tracks and mix the entire record. The other engineers were Woody Woodruff and Armin Steiner. Ironically, even though many of the sessions took place inside Capitol's Studio A, where Nat Cole used to record and which is favoured by both LiPuma and Fischer, the title song itself was tracked at Oceanway's Studio B, a preferred destination for Foster.

"Natalie's very easy to record," says Schmitt. "At one point, instead of being in a vocal booth, she came out and stood right there with the orchestra, à la Frank Sinatra. She was amazing. I used a Neumann U67 on her voice, along with just 2dB of a Summit limiter and a Neve 1073 preamp. I like the 67 a lot, it seems to work well on vocals, and with her it worked really well. When her father recorded 'Unforgettable', he used a 47, and the 67 matched up pretty well with that.

"Way back, when I started in the business, we didn't have limiters to use on the vocal, so we did most of the limiting by hand. You learned the song quickly, and where the artist got big you were able to pull back the level, while you'd increase it where the artist got softer. Since I think this approach produces better results, I still work mostly that way — whereas a limiter can pull a voice back, when you're hand-limiting you know exactly how far to go and can attain much greater accuracy. Nevertheless, I used a tiny amount of Summit limiter on Natalie's voice for the warmth of the tube, and, as she's got a fairly good microphone technique, that was easy to do. I recorded to analogue tape, +6 at 30ips."

"I do all of the miking myself," Schmitt continues. "My assistants will know what mics I want and generally where I want them to be, and they'll put them out there, but then before a downbeat when the musicians are there I'll go into the room and place every microphone exactly where I want it. I check the piano mics, I check all the drum mics, I place the string and brass mics, and I always make sure that all of the musicians are comfortable. If you've got happy, comfortable musicians, you're gonna have a great day; if you've got guys who are unhappy and uncomfortable with the way they're set up, it's gonna be a little bit more difficult."

"I do all of the miking myself," Schmitt continues. "My assistants will know what mics I want and generally where I want them to be, and they'll put them out there, but then before a downbeat when the musicians are there I'll go into the room and place every microphone exactly where I want it. I check the piano mics, I check all the drum mics, I place the string and brass mics, and I always make sure that all of the musicians are comfortable. If you've got happy, comfortable musicians, you're gonna have a great day; if you've got guys who are unhappy and uncomfortable with the way they're set up, it's gonna be a little bit more difficult."

Down To A 'T'

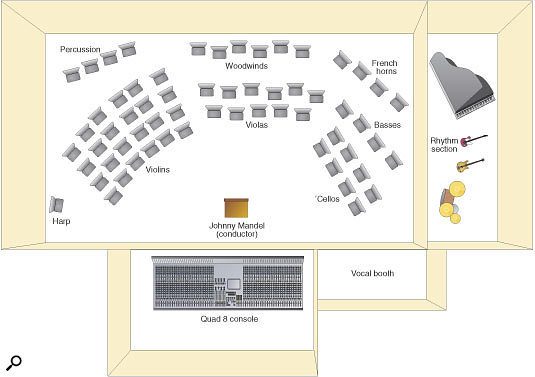

Working with a 55-piece orchestra at Oceanway for the 'Unforgettable' sessions, Schmitt employed a setup similar to the Decca Tree: three omnidirectional Neumann M50 tube condensers positioned in a T-shaped formation, with the left and right microphones approximately six feet apart, the central mic about four feet in front of them, and the entire array a couple of feet behind the conductor and between eight to 10 feet above him, pointing towards the musicians. In addition, Schmitt also miked the rhythm section.

The layout of Oceanway Studios during the recording of the new elements for the duet.

The layout of Oceanway Studios during the recording of the new elements for the duet.

"The miking can vary from session to session, but I try to use the same microphones whenever possible," he says. "In this case, I used an old Telefunken U47 on the upright bass — I like that mic's warmth, and its frequency response just enhances the bass sound. I've used it since I started, and it's very, very rare that I use anything else. Meanwhile, on the drums I used a couple of AKG 451s for overheads, 451s on the snare and hi-hat, 414s on the toms, and a D12 on the kick. Then, on the electric guitar and the harp I used Schoeps MK41s, while there were two [Neumann] M149s on the piano, Neumann U67s on the violins, violas and woodwind instruments, [Neumann] KM84s on the 'cellos, and [Neumann] M49s on the French horns. As for the percussion, I used some KM84s and a couple of AKG 452s."

Three Tracks Good

Creating the illusion of a duet between Nat 'King' Cole and his daughter was made much easier than expected by the fact that Cole Sr's original performance of 'Unforgettable' had been recorded on three-track tape. "We did a lot of stereo recordings back in the '50s," Schmitt points out with regard to a US scene which, by the end of the decade, included Tom Dowd doing eight-track work at Atlantic. "In '57, I worked on the Gerry Mulligan Reunion With Chet Baker and Songbook albums which were both in stereo. We had separate mics — we had the regular mics for the mono and then separate mics for the stereo, recording to a separate machine. Then, when I came to California in 1958, we went to three-track."

In the case of 'Unforgettable', Al Schmitt was relieved to discover that, unlike the three-track projects with which he had been involved, Nat King Cole's vocal was alone on the centre track. "We never kept the lead vocal separated in that way," he says. "Sometimes, I would place the rhythm section and the vocal in the centre, whereas when we went to four-track I'd place them alone on their own tracks and split the orchestra across the outside tracks. So, I was very surprised to hear Nat's vocal by itself in the centre, and that was a blessing.

In the case of 'Unforgettable', Al Schmitt was relieved to discover that, unlike the three-track projects with which he had been involved, Nat King Cole's vocal was alone on the centre track. "We never kept the lead vocal separated in that way," he says. "Sometimes, I would place the rhythm section and the vocal in the centre, whereas when we went to four-track I'd place them alone on their own tracks and split the orchestra across the outside tracks. So, I was very surprised to hear Nat's vocal by itself in the centre, and that was a blessing.

"When Natalie performed in Vegas, she would sing along to a video of Nat singing 'Unforgettable' — that's where the idea came from — so when we got the tape we knew what we were going to do. We knew there might be some problems, but we'd figure out a way to overcome them. Having Nat in the centre by himself on the three-track tape was totally unexpected, however — had that not been the case, we would have had to do a lot more filtering, and Johnny Mandel would have had to do a much, much more similar arrangement to the original.

"As it happens, by the time I heard the tape, Johnny already knew that Nat's vocal was alone in the centre, and he knew the spots where we wouldn't be able to remove stuff and where he'd therefore have to cover things up. Back in the early '50s the studios didn't have isolation booths. Nat was in the room with the orchestra, so there was some bleeding from the orchestra into his mic, and we therefore tried to filter out as much of that as we could. Still, there were spots where we just couldn't filter out the leakage, and so when Johnny Mandel did the arrangement for the new recording he compensated by way of writing similar instrumental parts to cover up the leakage in those particular areas.

"After the filtering process, we transferred the results over to 24-track analogue tape, and a famous old drummer named Sol Gubin, who'd played a lot of Sinatra dates, put a human click on it for the orchestral musicians to work to — as the Nat Cole recording had been made without a click, the tempos obviously varied quite a bit. Nat's vocal covered the entire song, and so we had the full orchestra play — and Natalie sing — to that, as well as to Sol's human click."

Recording An Orchestra

One of Al Schmitt's areas of expertise is tracking orchestras and large ensembles — when he was six and seven years old, he would visit his uncle's studio, Harry Smith Recording in New York City, and watch big bands being recorded with just a single microphone, necessitating soloists to walk to where the mic was, play their parts and then return to their seats. That was back in the early '40s, and when Schmitt himself began engineering during the next decade he soon learned about — and developed his own — multi-miking techniques.

"Through the years you do certain things that become recognised as an identifiable sound," he explains, "and that's down to microphone technique; the microphones you use and where you place them. So, that's what I think I bring to a session. I remember back in the '50s, when I was in New York, I was working with a drummer by the name of Tiny Cahn on a small jazz date and he asked me to put a microphone on the kick drum. Now, we'd use just one mic on the drums in those days, and since we were working with such a small section, I kinda looked at him as if he was strange, but I said, 'Sure, we'll give it a try,' and when I miked the kick it really made a difference. So, from that point on, whenever I could and whenever I had the availability, I tried to put a mic on the kick drum, and a lot of guys then followed suit.

"Other than that, it's difficult for me to identify specifically what I bring to the table. I know that I don't have any secrets and I try to teach my assistants the things that I've learned: where to place microphones, what not to be afraid of — you know, a lot of guys are afraid of the leakage problems in the studio, and I try to explain that if you use good microphones and you get this leakage, sometimes it's your best friend in the studio, helping to make something sound much bigger than it really is."

When I ask Schmitt if his approach is notably different to that of his fellow engineers, he laughs. "It was for a while," he says. "Even then, there were a few people who did work the same way, including Armin Steiner and Bruce Swedien. But what's happened is that a lot of the assistants with whom I've worked have gone on to work with other engineers on big string dates and big band dates, and the first thing these engineers will tell them is 'Set it up the way Al Schmitt sets it up.' So, they set up everything the way I do and they use the same microphones, and I'm therefore not so sure that what I do is as unique as it used to be."

Unforgivable?

The interim result was a spine-tingling duet featuring Nat Cole and his daughter, backed by an orchestra playing Johnny Mandel's adaption of Nelson Riddle's original arrangement. Several of the musicians, who had played on the original recording, were moved to tears, as was the lead singer, for as she would comment in the album's liner notes, the project was "a labour of love for myself and everyone that has worked on it".

"Natalie's an amazing singer, and she completed her vocal in three or four takes," Schmitt recalls. "We didn't need to do any punching in. David Foster produced this particular cut, and when we got into the mixing process he figured out where Nat and Natalie were each going to sing. This was helped by the fact that it was easier to mute Nat in certain spots and Natalie in others. However, while it was easy for her to sing answers to him, it wasn't quite so straightforward getting him to sing answers to her, and so what we had to do was put him in the sampler and move his vocal around.

"In terms of matching room sound, I changed the echo around a little bit — with Nat, the echo was on his voice, but I also added to it so that it matched up with Natalie's sound. In fact, in a couple of spots we did the unforgivable; we actually tuned Nat's voice. However, that was minor stuff. Overall his vocal was incredible. The consoles back in those days had very little; they didn't have the compressors or gates that we're now used to, so what you hear is his natural voice, and on 'Unforgettable' it sounded absolutely huge. As a result, one of the problems we had was trying to get Natalie to match that, and that took a lot of work, trying to duplicate the echos and levels and so forth.

"Afterwards, when the album won a Grammy for Best Engineering, everybody said, 'Oh my God, the title track's incredible! How did you do that?' Well, it was a pretty simple process, and today, thanks to Pro Tools, it's a hell of a lot easier to do than it was back then. The most difficult part was stripping Nat's vocal and getting him on there, whereas the rest was just like a normal recording. Still, that having been said, even if we had Pro Tools back then I wouldn't have used it, because the early Pro Tools sounded terrible. Now, I use it quite a bit, because I love the 96k or the 192, and I think it sounds really good and is so much closer to the analogue."

Not Much Mixing Required

In addition to Johnny Mandel, other arrangers on the Unforgettable album included Marty Paich, Michel Legrand, André Fischer, Clare Fischer, Ray Brown, Ralph Burns and Bill Holman. Since both Burns and Holman had worked with big bands during Nat Cole's heyday, they were brought in on the project in order to provide it with some of that authentic flavour. On the Bert Kaempfert/Milt Gabler composition 'L-O-V-E', for instance, Holman oversaw five saxes, four trombones, four trumpets and a rhythm section. Al Schmitt employed M50s as room mics, U67s on the brass, and the aforementioned setups on bass, drums, piano and guitar.

"When I used 67s on the band I had them all in a non-directional pattern," he says. "They were open omni, and the reason for that is, because the trumpets and trombones play so loud, you don't worry about much stuff leaking into them. You achieve a bigger and better effect by going for the overall room sound. What's more, I did have the drums isolated in a booth, so I wasn't worried about them leaking in."

Schmitt states that, when he's recording, he is constantly mindful of the upcoming mix: what echos he will use, how he will take care of the panning, and so on. To that end, either he or his assistant will keep notes on what he is doing and how he is doing it. That way, when he actually gets to the mix, the procedure is fairly straightforward.

"I know pretty much how I'm going to lay out the board and what form the panning will take," he says, "and then it's just a matter of balancing and echo, and if I need to use a little EQ on something to bring up the high end I might do that too. On 'Unforgettable', David Foster left pretty much everything up to me. He would come in and listen and say, 'Yeah', or 'I need a little more of this and a little more of that,' but in general he'd leave me alone and I would get the whole thing together, and then he'd come in and we'd do some tweaking. However, it was some pretty minor tweaking at that point."

All in all, Al Schmitt confirms that the Unforgettable project was just that for everybody involved: a memorable experience that pertained especially to the title track. "David Foster certainly knows what he is doing," he says, "so he had his job down, Johnny Mandel had his job down, I had my job down, the musicians had their jobs down, and between us we made it work."