The single 'Downtown' gave Petula Clark a worldwide hit and rejuvenated her career. Presiding over the session was engineer Ray Prickett, who tells us how it happened...

Petula Clark with a gold disc for 'Downtown', 1965.Photo: R McPhedran/Express/Getty Images

Petula Clark with a gold disc for 'Downtown', 1965.Photo: R McPhedran/Express/Getty Images

Nowadays, orchestral pop hits are largely a thing of the past. It is no longer a common occurrence for contemporary singers to be tracked live in the studio alongside string, horn, and woodwind sections, as well as electric guitars, keyboards and drums. But it was the standard way of working back in October 1964, when Petula Clark recorded 'Downtown' at the Pye Studios on London's Marble Arch.

Released the following month, it became a number two UK hit that December and a US chart-topper in January 1965. This celebration of curing life's problems by revelling in the bright lights, neon signs and "music of the traffic in the city” was not only the perfect encapsulation of pre-psychedelic swinging '60s optimism, but also a classic example of the brilliantly arranged, instantly infectious three-minute single that melded mod sensibilities with showbiz polish. And to think, the lyrics penned by its English composer/producer were not even inspired by the attractions of his nation's suddenly in-vogue capital.

"'Downtown' was written on the occasion of my first visit to New York,” Tony Hatch would later recall. "I was staying at a hotel on Central Park and I wandered down to Broadway and to Times Square and, naively, I thought I was downtown — forgetting that, in New York especially, downtown is a lot further downtown, getting on towards Battery Park. I loved the whole atmosphere there and the song came to me very, very quickly.”

'We Need A Hit...'

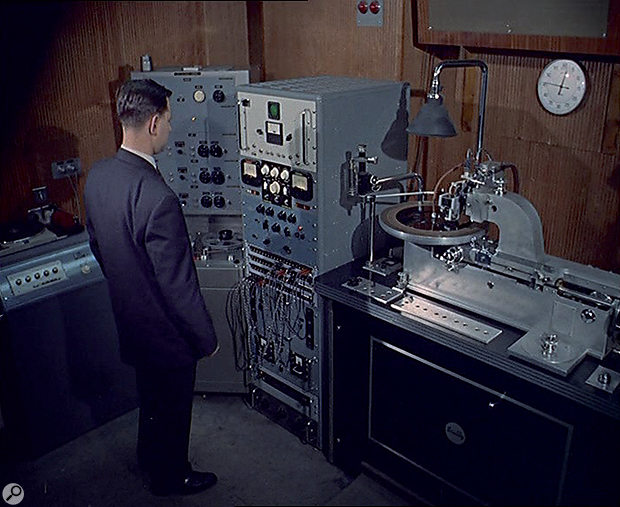

The control panel of Pye's three-track Ampex (not the four-track used on 'Downtown'). Photo: British Pathé

The control panel of Pye's three-track Ampex (not the four-track used on 'Downtown'). Photo: British Pathé

A child star of film, TV, radio and record, known in the 1940s as 'Britain's Shirley Temple', Petula Clark had been signed to Pye since 1955 and enjoyed her first UK number one in 1961 with 'Sailor'. Although Alan A Freeman had produced that track, as he had all of Clark's recordings since 1949, his assistant on the 'Sailor' session was Tony Hatch, whose first song recorded by her was the 1963 flop 'Valentino'. Thereafter, Hatch took over as her producer and capitalised on Petula's popularity in Europe via some French-language releases.

At home, it was a different story. A string of nondescript singles meant that, by 1964, she was in dire need of an English-language hit, so Hatch visited her home in Paris to play her three or four songs he had acquired from music publishers on a trip to New York. Pet wasn't impressed... until she heard a few bars of an incomplete soul number that Hatch intended offering to the Drifters.

"We already knew that we had to make a record,” Hatch recalled in a 2009 interview with Gary James. "I had a studio booked with an orchestra, ready to do a new recording session with her. And she said, 'Aren't you working on anything yourself?' Reluctantly, I played her the idea of 'Downtown', because I'm always reluctant to play half-finished songs. She immediately saw tremendous potential in it. She was the one who said, 'Get that finished. Get a good lyric in it. Get a great arrangement and I think we'll at least have a song we're proud to record even if it isn't a hit.'”

The Session

A mono Ampex tape recorder from Pye's studio 1. Photo: British Pathé

A mono Ampex tape recorder from Pye's studio 1. Photo: British Pathé

The 'Downtown' session took place about two weeks later, on 16th October, 1964. Thirty minutes before it commenced, Tony Hatch was still fiddling with the lyrics in the studio's lavatory. This was because when he took charge of a production — as he had already done with the Searchers (for whom he'd penned the hit release 'Sugar & Spice' under the pseudonym Fred Nightingale) — he insisted on everyone recording together at the same time, be they members of a four-piece group or, as in this case, a large ensemble. The musicians assembled included eight violinists, two viola players and two cellists, four trumpeters and four trombonists, five woodwind players with flutes and oboes, percussionists, a bass player and a pianist. Also present was famed session drummer Ronnie Verrell (not Bobby Graham, as has been erroneously reported elsewhere), female vocal trio the Breakaways, whose backing-singer credits would soon range from Dusty Springfield to the Jimi Hendrix Experience, and session guitarists Big Jim Sullivan, Vic Flick and Jimmy Page.

"Quite often on the Hatch sessions, not only did we have Jim Sullivan and Jimmy Page, but also John McLaughlin sitting in as part of the rhythm section,” says engineer Ray Prickett, who recorded 'Downtown' in Pye's Studio 1. "Can you imagine being around that collection of talent? For 'Downtown', looking down on the live area from the upstairs control room, the drummer was in the far right corner, the bass player was to his left (again, from our perspective), the guitarists were about halfway along the right-side wall, the percussionists were at the near end of that wall, the pianist was in the middle of the studio and Tony's arranger Bob Leaper was conducting nearby. Opposite the control room, near the facing wall, was where Petula and the vocal group were set up, with a few small screens between and around them to provide a little bit of separation. The strings were to the left of them (as we were looking at the room) facing towards the conductor, and further left was the brass section, while the woodwind were in front of the string section.

"When you listened to any of the mics, there wasn't full 100 percent separation. Not by a long way, because that wasn't what we were aiming for. The way I saw it, and Tony agreed with this, was that the sound wasn't as good when we recorded different sections separately. When the whole orchestra plays together, something happens — all of the air is being moved by those instruments and that's what gives you a big, ambient sound. This is why there was minimal screening even around the vocalists; maximum separation would have defeated the object of having all those people playing in that room.

"Since their playing was well controlled, Pet Clark was somehow able to hear herself singing. The vocalists didn't use headphones as often in those days as they would later on, and there also wasn't much [loudspeaker] foldback. Until we replaced it with a Neve in 1965, we had a four-track Neumann desk in Studio 1. Later desks would actually have more controls for foldback than for mixing, and the trouble was, when you had the ability to work more than two or three different mixes of foldback, it became a bit of a pain. At that point, everybody wanted to hear their own little mix, and this, in my opinion, detracted from the spontaneity of the overall sound.”

Career Engineer

Engineer Ray Prickett in the control room of Pye's Studio 1. This and the following photos are taken from a 1963 Pathé newsreel which featured the Searchers recording their hit single 'Sugar & Spice'. While the session was artificially recreated for the film, the pictures show a fascinating view of Pye Studios as it was at the time 'Downtown' was recorded in the mid-1960s. Photo: British Pathé

Engineer Ray Prickett in the control room of Pye's Studio 1. This and the following photos are taken from a 1963 Pathé newsreel which featured the Searchers recording their hit single 'Sugar & Spice'. While the session was artificially recreated for the film, the pictures show a fascinating view of Pye Studios as it was at the time 'Downtown' was recorded in the mid-1960s. Photo: British Pathé

Ray Prickett had no such concern when, as an 18-year-old in 1952, he gained his first studio experience. This was at a facility named Gui de Buive, where he worked with tape and direct-to-disk recording before landing a job three years later as a cutting engineer at IBC. In 1958, IBC became the first UK facility to be equipped with a stereo lathe, and it was there that Prickett also tracked easy listening, orchestral-pop sessions, including several produced by the aforementioned Alan Freeman (not to be confused with the disc jockey of the same name). This, in turn, paved the way for the fully fledged engineering work that Prickett did after moving to Pye in 1963, recording anyone from Lonnie Donegan and Kenny Ball to the Searchers and, of course, Petula Clark.

"Whenever Tony Hatch was with me in the control room, we had such a good understanding that, by the time he'd ask me to add something, I had already done it,” remarks Prickett, concurring with what Hatch himself told an interviewer in 2005: "Bob Leaper was my musical associate. I would do a run through of each item with the orchestra myself, check notes, et cetera, get the right feel, then Bob would take over when I went to the control room. I worked with balance engineer Ray Prickett so many times... he knew exactly what I wanted. I've always had a great rapport with musicians and studio personnel, so the job becomes an enjoyable team effort.”

Recording The Pye Way

Located inside ATV House, Pye had two studios: the 40 x 30 x 18-foot room where 'Downtown' was recorded and the 20 x 20 x 18-foot Studio 2. The former, in addition to its Neumann console, housed an Ampex four-track tape machine, Tannoy dual-concentric speakers inside Lockwood cabinets, an echo chamber, a couple of rooms with EMT 140 echo plates, and a good selection of mics that included Neumann U47s, M49s and an SM2 (and, later, U67s, U87s and KM84s), AKG C12s and Sennheiser MD421s.

Ray Prickett looking down from the control room into the live room of Pye's Studio 1.Photo: British Pathé"I'd use three mics to record the drums,” Prickett explains. "Usually a 421 on the bass drum and then two 47s, 67s or 87s as overheads — whatever was available at that time. We would train a lot of young engineers at Pye, and one of them once came to me and said, 'Come and listen to this drum sound that I've got!' This was when we'd already upgraded to 16- or 24-track. He said, 'Listen to the snare. Doesn't it sound great?' and I said, 'Yes, great, great,' and then he asked me to listen to the bass drum. Eventually, I said, 'Let's listen to the whole lot together... Have you listened to the whole lot together?' 'Oh no,' he said, 'I haven't done that yet,' so I said, 'Well, then do it.' When he did, his face fell — he couldn't believe the top-less sound that he'd got. 'Why's that?' he asked me, to which I said, 'You've got too many mics too close together. You got so much phase shift there, you're losing all your top end. You've made it over-complicated.'

Ray Prickett looking down from the control room into the live room of Pye's Studio 1.Photo: British Pathé"I'd use three mics to record the drums,” Prickett explains. "Usually a 421 on the bass drum and then two 47s, 67s or 87s as overheads — whatever was available at that time. We would train a lot of young engineers at Pye, and one of them once came to me and said, 'Come and listen to this drum sound that I've got!' This was when we'd already upgraded to 16- or 24-track. He said, 'Listen to the snare. Doesn't it sound great?' and I said, 'Yes, great, great,' and then he asked me to listen to the bass drum. Eventually, I said, 'Let's listen to the whole lot together... Have you listened to the whole lot together?' 'Oh no,' he said, 'I haven't done that yet,' so I said, 'Well, then do it.' When he did, his face fell — he couldn't believe the top-less sound that he'd got. 'Why's that?' he asked me, to which I said, 'You've got too many mics too close together. You got so much phase shift there, you're losing all your top end. You've made it over-complicated.'

"That was basically my theory: if you've got too many mics on a drum kit, you get phase shift. Because a kit is a very tight little unit, you can't afford to put separate mics on the cymbals, hi-hat and so forth. Whatever happens, you're going to get spill, and the phase shift caused by the various spacings of the mics will detract from the overall sound. You should get a nice, clean, top-end sound on the kit, and that requires just two mics overhead and one on the bass drum.”

Without a doubt, this worked on 'Downtown'. Ronnie Verrell's drumming, deft yet with a light touch, features prominently — courtesy of a solid bass drum, heavy snare backbeat on the choruses and crisp ride cymbal — while fitting in with the rest of the instruments. A case of perfect blending rather than perfect separation, this was balancing done the organic, old-fashioned way, and the results speak for themselves.

"For the bass guitar, we didn't DI much in those days, so we would have miked the amp,” Prickett continues. "We of course did the same with the electric guitars, there would have been a mic on the acoustic, and for the piano I used the stereo SM2 — the lid would be partly open with the mic inside, and then we'd put a cover over the top just to keep some separation.

"For the strings, I'd use two mics as a stereo pair on the eight violins, and then one each on the pair of cellos and pair of violas. Then there would be no more than three mics on the woodwind section, two on the trumpets, another two on the trombones, and either U47s or U67s on the vocal and backing vocals.

"For the strings, I'd use two mics as a stereo pair on the eight violins, and then one each on the pair of cellos and pair of violas. Then there would be no more than three mics on the woodwind section, two on the trumpets, another two on the trombones, and either U47s or U67s on the vocal and backing vocals.

"In all, we probably did four takes — sometimes we got away with less than that — and we also did some editing, maybe editing the brass middle-eight out of one take and inserting it into another take that we preferred because of the vocal. Working four-track, we'd always do a straight stereo mix of the entire orchestra and all of the other musicians, there and then, completely live. What we got on the session is what you hear on the record, and the other two tracks had Pet Clark and the backing singers.”

Whereas most British studios of that era adhered to a strict timetable — with sessions running from 10:00am to 1:00pm, 2:00pm to 5:00pm and 7:00pm to 10:00pm — Pye's engineers were used to often working beyond the regular recording sessions into the wee small hours so that they could finish a mix and meet the deadline for delivering the finished product to the pressing plant a few hours later.

"I got blacklisted at a very early stage in the business,” Ray Prickett laughs when asked whether such work practices contravened union rules. "Pye was actually a non-union studio and it was meant to be that way.”

For the mix of 'Downtown', since the stereo musical backing had already been mixed live, Prickett's main task was to just add the lead and backing vocals at the desired levels.

"We'd pan the mix as we went along,” he says, "usually with the rhythm mainly in the centre, the strings spread left and right, the trombones and trumpets split from the point of view of the stereo mix, and the woodwind panned across the middle. So, it was a nice big spread of sound.”

Aftermath

Evidently, the record-buying public agreed. Following its release, 'Downtown' not only ended a two-year chart absence in the UK for Petula Clark, but during its three-week stay at number two in December 1964, the single was only kept from the top spot by the Beatles' 'I Feel Fine'. Certified silver for domestic sales of over half a million, it also hit the top five in countries as far apart as Ireland and India, while going all the way to number one in the English-speaking territories of Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and Rhodesia. Still, its greatest triumph was reserved for an America that was in the full throes of the so-called 'British Invasion'.

Given that Tony Hatch had first thought about writing 'Downtown' while standing in New York's Times Square (which, he didn't realise, is actually part of the city's midtown), he was concerned that Warner Bros A&R exec Joe Smith would think Petula Clark's unmistakeably English accent sounded ridiculous when she sang Americanisms such as the song's title, "sidewalk” instead of "pavement”, and "movie shows” instead of "cinemas”. He needn't have worried. As soon as Smith heard the record in Hatch's London office, he loved this "observation from outside of America” that, to his mind, was "just beautiful and just perfect.” In fact, such was Smith's enthusiasm, it even inspired Pye executives to give the single a stronger sales push in the UK, where it would scoop an Ivor Novello Award as 1964's 'Outstanding Song Of The Year'.

Released by Warner Bros that December, 'Downtown' repaid Joe Smith's faith by making its way into the top 10 of the Billboard Hot 100 within five weeks. Then, on 25th January, 1965, it commenced a fortnight's stay at number one, making Petula Clark Britain's first female chart-topper in the US during the rock era (just over 12 years after Vera Lynn had achieved a similar feat). It also made her the first British girl singer to also earn a gold record in America for sales of one million copies, and the recipient of a Grammy for 1965's 'Best Rock & Roll Song'.

"She was a total professional and very easy to work with,” says Ray Prickett, who remained with Pye until 1978. His many other credits including all 14 of Petula Clark's subsequent consecutive US top 40 hits — 'Colour My World', tracked at LA's Western Recorders was credited by Phil Spector's drummer of choice, Hal Blaine, as featuring his best drum sound there. Additionally, Prickett recorded artists such as Donovan, Dionne Warwick, Trini Lopez, Sounds Orchestral, Jay & the Americans, and Françoise Hardy before going freelance and focusing on location work, mainly with military bands. He ended his 56-year career by retiring in 2008.

"I grew tired of working in the studio when there was no longer any longevity to what was being recorded and multitracking was making everything so time-consuming,” Prickett explains. "This was completely different to how things were up until the early '70s, when we worked quickly and compiled a great catalogue of material that would keep selling well into the future.”

A case in point: the 1964 recording of 'Downtown' which not only surfaces regularly on radio, TV shows and film soundtracks, but has also been remixed and re-released three times; in 1988, 1999 and 2003. What's more, in addition to the multitude of cover versions by anyone from Frank Sinatra to the B-52s, Petula Clark herself has re-recorded the song several times: in 1976 (with a then-trendy disco beat), 1984, 1988, 1996 and, in December 2011, as a duet with Irish rockers the Saw Doctors. Not bad for a chanteuse who has just turned 79.

"We had no idea that we were recording a monster,” she said when discussing the original, classic version in a 1999 radio interview with Kool FM in Phoenix, Arizona. "You never do. You just go in and do a song you like and it's the public who decides that it's going to be a hit...”

Disc Cutting

Cutting Engineer Derek Moore in one of Pye's two cutting rooms. Photo: British Pathé

Cutting Engineer Derek Moore in one of Pye's two cutting rooms. Photo: British Pathé

Although Ray Prickett didn't work as a disc cutter at Pye, his previous experience in this field nevertheless proved beneficial to the records that he engineered.

"We had two cutting rooms with Scully lathes,” he says, "and I remember one of the engineers there asking me, 'Why is it we never have to do anything to your stuff other than just cut it?' I said, 'Well, I used to be a cutting engineer.' The guys there reckoned that all recording engineers ought to learn a little about cutting.

"As we all know, in those days the LP was really a compromise in terms of capturing what was on the tape — particularly the stereo LP. There would be two drivers running at a 45-degree angle to the surface, and you could actually cut a groove shaped in such a way that it would be almost impossible to separate when they were pressing — it was like an under-cut. That's why, if you listen to most records of that period, a heavy bass would usually be placed in the middle. Otherwise, if you put the bass on one side, it made it very difficult for cutting. These were the sorts of things one learned back then...”