From left to right: Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and David Crosby at Wally Heider Studio 3, February 1969.Photo: Henry Diltz

From left to right: Stephen Stills, Graham Nash and David Crosby at Wally Heider Studio 3, February 1969.Photo: Henry Diltz

As the '60s drew to a close, David Crosby, Stephen Stills and Graham Nash came together to form a new group, the unique sound of which was perfectly demonstrated by their first recording, 'Suite: Judy Blue Eyes'.

It was 1968, and at a time when loud blues‑based rock was all the rage, along came Crosby, Stills & Nash to help redraw the musical landscape with their characteristically seamless blend of folk, country, jazz, blues and rock, featuring high, sublimely intricate three‑part harmonies.

While the prominent folk‑rock sensibilities of ex‑Byrd David Crosby were supplemented by his compositional talent for atmospheric tunes and socio‑political lyrics, country‑oriented former Buffalo Springfield frontman Stephen Stills was a remarkable multi‑instrumentalist with the ability to make seemingly disparate musical elements coalesce. Add to this the melodic pop skills that Graham Nash had refined with the Hollies and the result was a timely, all‑encompassing fusion of great commercial, critical and artistic appeal. In essence, CS&N brought singer‑songwriters firmly into vogue and paved the way for acts like the Eagles by helping to define the new, freewheeling 'California Sound' of the early '70s.

Coming Together

Right from the start, it was all there (even before the addition of Stills' Buffalo Springfield co‑founder Neil Young), as evidenced on the eponymous debut album that immediately endowed the group with superstar status. Recorded during February and March of 1969, this highly influential 10‑track opus earned CS&N a Grammy for Best New Artist, courtesy of songs such as 'Suite: Judy Blue Eyes', 'Marrakesh Express', 'Guinnevere', 'Wooden Ships' and 'Long Time Gone'.

The trio had first harmonised together on Stephen Stills' 'You Don't Have to Cry' during a party at the home of either Mama Cass Elliot (according to an adamant Stills) or Joni Mitchell (according to both Crosby and Nash) the previous June. Encouraged by Doors producer Paul Rothchild, they had then recorded a five‑song demo in New York that, despite being rejected by the Beatles' Apple label, had earned the brand new group a contract with Atlantic.

In the meantime, Crosby and Stills had joined Nash in London to write some fresh material, and after rehearsal sessions at the Long Island home of the Lovin' Spoonful's John Sebastian in January 1969, they were ready to roll. Album sessions commenced at Wally Heider's Studio 3 in Los Angeles the following month, with the three group members sharing the production chores while Bill Halverson engineered and Stills played virtually all of the instruments. That was, aside from the drums, behind which sat former Clear Light member Dallas Taylor; Dave Crosby's rhythm guitar; and the acoustic guitar and percussion played by Graham Nash.

"Nobody sounded quite like those guys back then,” says Halverson, whose methods of recording CS&N's vocals and guitars proved to be not only successful, but highly influential. "Stephen was an unbelievable musician, and the way they blended their voices was just incredible.”

Songs Of Experience

Engineer Bill Halverson in the Studio 3 control room, February 1969. Behind him you can see a rack of silver-face Universal Audio 1176s.

Engineer Bill Halverson in the Studio 3 control room, February 1969. Behind him you can see a rack of silver-face Universal Audio 1176s.

Halverson first met Wally Heider back in 1960, when the former was playing bass trombone in an all‑star jazz band at LA's Dominguez Hills Junior College. At that time, Heider was a second engineer at Bill Putnam's studio, United Recording, and when he was invited to record one of the band's rehearsal sessions, he reciprocated by telling the musicians they were welcome to attend a proper tracking session at United. That summer, shortly before performing with the band at the Third Monterey Jazz Festival, Halverson took Heider up on his offer, and while spending the next four years touring with the jazz outfits of Allen Ferguson and Tex Beneke, he struck up a friendship with Heider. Indeed, Halverson even assisted Heider on some of his remote recordings around LA and Las Vegas.

By the time that Halverson quit Tex Beneke's band in November 1964, Heider had also left United Recording to launch his own LA studio near the intersection of Selma Avenue and Cahuenga Boulevard. The very next month, Halverson was working there as an assistant engineer, and although he initially considered this to be a temporary job, it turned into something far more permanent. The facility's first console was one designed by Bill Putnam, and this would even be used in the mobile truck — such was the case when Halverson watched the Capitol Records engineers use it to capture the Beatles' 1965 concert at the Hollywood Bowl. Back at the studio, he also gained invaluable experience watching Heider behind the board, while observing how an independent Nashville engineer named Jimmy Lockhart interacted with Brian Wilson on some Beach Boys sessions.

"I remember it so clearly,” says Halverson, who went freelance in 1970, 15 years before relocating to Nashville, where he is currently working on his memoirs. "When Brian tried to tell Jimmy something, Jimmy would respond, 'Well, show me. Use this knob right here.' Brian would say, 'Can I touch it?' and Jimmy would say, 'Yeah, just show me how you want it.' So, Brian would try the level, and even if it wasn't quite right, it would give Jimmy an idea of what he wanted. At that point, Jimmy would take over and go, 'You mean like this?' and Brian would say, 'Yeah, yeah, that's what I want.' Watching that kind of interaction certainly helped me later with people like Stephen Stills.”

Studio 3

Studio 3's 16‑track Frank DiMedio custom‑designed valve console and the remote control for the 3M tape machine.

Studio 3's 16‑track Frank DiMedio custom‑designed valve console and the remote control for the 3M tape machine.

When space became available adjacent to Wally Heider's studio, Heider considered acquiring it to replicate what was then the busiest facility in town: Studio 3 at Bill Putnam's United Western Recorders.

"Wally and his carpenter, a guy named Hal Halverson — no relation to me — booked an hour of studio time at United Western 3, measured it and figured out it would fit into the space that was available,” Bill Halverson recalls. "So, that's how Heider came to build his own Studio 3. He never did have a Studio 2; he actually had the balls to name it Studio 3. Then, in an effort to get Bones Howe — who had engineered so many hit records at United Western 3 — to move some of his business over to Heider Studio 3, Wally asked him, 'What do I need to get you?' Maybe that was a flip remark, but Bones said, 'Well, I want 16 of those Universal Audio equalisers and 16 of those Universal Audio filters in the rack so I can run everything that way.'

"That's what Heider did. He went out and bought Pultecs and Universal Audio with the 175B and 1176 limiters, doing whatever Bones wanted in order to get him over there. Then there was a 16‑track Frank DiMedio‑designed valve console comprised largely of Universal Audio components, together with an Ampex 300 two‑inch tape machine that DiMedio had jury‑rigged with Ampex 350 electronics. This was before we got the API board and 3M 16‑track machines. The Ampex was 15ips, and I was one of the few guys who never went to 30ips because the bottom end at 15 was so fat that I became addicted to it.

"Although that studio was a little longer and a little narrower than Studio 3 at United Western, it was basically the same and it was a brilliant room. I didn't actually know how good that room was until I left Heider's and started recording in other rooms that weren't nearly as forgiving.

"We'd usually put the drums and bass on the right side of the room and the guitars on the other side, and I did a live Tom Jones vocal in there and got away with it. I also cut [Cream's] 'Badge' live in there with Felix Pappalardi's piano, and again we got away with it, even with Marshall amps going full blast. It was just a very forgiving room.”

Working Backwards

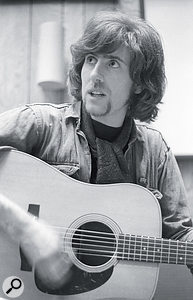

Left: Graham Nash playing acoustic guitar.

Left: Graham Nash playing acoustic guitar.

Having helped Wally Heider record 1967's Monterey Pop Festival, Bill Halverson was already familiar with David Crosby. He had also met Stephen Stills, having helped Jim Messina track a Stills overdub on Buffalo Springfield's album Last Time Around in Studio 1. However, it wasn't until he engineered a demo session in late 1968 that Halverson really got to witness Stills' remarkable talent.

"He came in and played some acoustic guitar and did some vocals and played some bass,” Halverson recalls, "and then he rented some drums from Studio Instrument Rentals — which was the big rental company out there at that time — and played those, too. The song was '49 Reasons', before it became '49 Bye‑Byes' — it was an eight‑track demo, and when he wanted to turn the tape over I had no idea what he was doing. Track two became track seven, and he did this backwards guitar thing where he could hear the changes backwards and play this part. He only did it one time, turned it over and the guitar part just blew me away.”

After Halverson recorded a demo in Studio 3, featuring a folk singer named Judy Mayan who was being produced by David Crosby and the Monkees' Peter Tork, he began managing Wally Heider's while the owner was building some new facilities in San Francisco. That was when he received a call from Atlantic requesting time to be blocked for an unknown group that wanted to use Studio 3 in early 1969. Cue the Crosby, Stills & Nash project, which was the first time Halverson engineered an entire album. (Contrary to subsequently published credits, he does not claim to have co‑produced.)

Busking It

Stephen Stills tracking bass in Studio 3's live room.

Stephen Stills tracking bass in Studio 3's live room.

"On the first day, when they walked in, I had no idea what we were going to do,” says Halverson, whose other credits include Jimi Hendrix, Joe Cocker, Chuck Berry, the Beach Boys, Eric Clapton, Kraftwerk, Emmylou Harris, Stephen Stills and, of course, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. "I had kept asking Atlantic for a setup — was there going to be a drummer, a bass player and an entire band? — and all I heard back was 'We don't know. They've booked the time and they'll be there, so you'll just have to wait and see.' Then, when they did arrive, it was just the three of them in David's VW van with a couple of guitars and a bass. So, we loaded the stuff in and hung out for a bit. Graham had never been in the studio. Finally, I said, 'So, what are we gonna do?' and was told, 'Stephen's going to play a little acoustic guitar.' That's how it started. I had no idea they'd already been rehearsing, I had no idea what kind of music it was going to be.

"I went and got a really nice acoustic guitar mic, a tube Neumann U67, and I set it up, got Stephen some headphones so he could hear what he was doing, and after I'd turned the lights out according to his request, he started playing. At this point, having watched Wally Heider record Wes Montgomery and other jazz musicians, and even though I'd done rock & roll with some electric stuff, I was pretty much a purist. So, when the old Martin D28 that Stephen played sounded really dull to me, I started adding top end and using those equalisers that we'd got for Bones Howe, while also putting a limiter on it and taking all the bottom‑end off. I just kept trying to brighten it up and get it a little more present, and once I had it sounding pretty good I thought I'd record a little, let him take a listen, and then see if he liked it and how we could change it. I was really trying to please.

"So, with David and Graham sitting next to me, I started to roll tape on the 16‑track and David signalled this to Stephen by making a circular motion with his hand above his head. Until then, Stephen had just been goofing around on his guitar, but suddenly he zeroed in on the microphone and started flailing away, and the sound was so bright that the compressor was way over‑compressed — instead of bouncing around like compressors do, it just laid down and sat there. There was also no bottom end. However, from my training with Heider I knew that I couldn't stop the take; I had to just let it go and then explain the problem and try to fix it later.

"Sitting there, I was already thinking about the things I could do to fix it, because I had totally overdone the sound, but Stephen was totally into what he was playing, and just when it looked like he was going to stop, he started another section and played some more. By now, my whole life was flashing in front of me, and certain that my career was over, I began to sweat. Meanwhile, Crosby and Nash were standing next to me, dancing — they were having a good time — and it wasn't until seven and a half minutes into the recording that the whole thing ended. Stephen had just played the basic track to 'Suite: Judy Blue Eyes'...

"It still gives me goose bumps when I listen to that recording, aware that he blew through seven‑and‑a‑half minutes with all the time changes, all the pauses, all the everything in just one take,” Halverson says. "No edits, no nothing. Anyway, when Stephen was done and I could hear him taking off his headphones, I figured he was going to come in and just blast me for the horrible recording, so I was ready with my excuses. David and Graham met him at the double doors, and while they were all high‑fiving each other Stephen turned to me and said something to the effect of, 'Oh, that's the sound I've been looking for! I love it!' and I went, 'Thanks.' I was just dumbfounded. For the next 20 years, I didn't tell him it was an incredibly happy accident, and that if I had known what I was doing he wouldn't have got what he wanted.”

A Group Effort

Above: David Crosby listening to playback.

Above: David Crosby listening to playback.

"After Stephen had recorded his acoustic guitar part, he, David and Graham were ready to sing, and for that I was ready. We had done all kinds of jingles in the little room at Heider's, from the Anita Kerr singers to Jan and Dean, and so I just took the Neuman U67, opened it all the way around [ie. put it into omni mode], gave them three sets of headphones and went, 'Sing!' Singing into the one mic, they moved around a bit. They didn't need any music; they were rehearsed, they knew the lyrics, and while harmonising with each other they were also in the process of amazing each other.

"What I'd also learned to do by then was save what I thought was the good stuff, and with 16 tracks that was easy to do. So, through the course of that whole album I never played them what they had done; I only played them what they were doing. They were out there for a couple of hours, and when they finally came in to listen I had three tracks of 'Suite: Judy Blue Eyes' just about completely recorded. I thought, 'What the heck, I'll play it all for them,' so I turned up the guitar, spread out the three tracks and pushed 'Play', and they had no idea what was coming. They had three passes of the three of them and it was brilliant. They were so tight and so rehearsed.

"Once in a while, if a part was out of sync we'd go back and fix it. But for the most part they'd all just get around one mic and sing. That having been said, where Stephen's singing by himself on 'Suite: Judy Blue Eyes' you can hear the double, and that's to avoid phasing. They were so perfect that, if you brought the three vocal tracks up at the same level, the meters would phase and it would be difficult to master. That's why, when we mixed it, there was this dance that I would do with the three levels of the three tracks so that they were never always completely equal, and the result is that it doesn't sound like three tracks all the way through all of the time — one track is usually slightly ahead of the others, and it is those tiny bits of movement in a track that keep it from phasing.

"In one part of the song there's the line 'Friday evening, Sunday in the afternoon,' and then Stephen goes, 'Oh, oh, oh.' That's him singing the 'oh' on three different tracks in three different spots, and they thought that was cool because it was kind of syncopated, so we left it. Next, Stephen laid down a bass part — recorded DI or with a Shure 546, the forerunner of the SM57 — and again this was at 15ips for a big, fat sound while going through one of the UA limiters. That evening, we also cut 'You Don't Have To Cry' in the same way. So, on the first night, we recorded two songs with acoustic guitar and vocals.”

While Stills added some percussion, including a conga‑type sound at the end of the song that was attained by beating the back of his Martin guitar, he was also responsible for the various sonic textures that he created with the electrified instruments.

"When it comes to all the electric guitar parts on the early stuff, I'd love to take credit for being the brilliant engineer with Stephen,” Halverson remarks. "However, the reverse is true. All of those different guitar sounds were basically achieved by me sticking a Shure 546 in front of an old brown Fender amp, and the different sounds of the different amps were down to Stephen. Since we hardly had any effects back then aside from the really wonderful stereo echo chamber in Wally Heider's Studio I, he might go, 'I need it to be bigger,' and we would end up with an RCA 44 at the other end of the room and then mix that and the Shure together. Or we would take a direct and mix it with the amp — we'd keep trying different things to get what he was hearing in his head.”

Group Mix

A true band effort, unlike the subsequent CSN&Y album Déjà Vu that would see the participants contributing most of their parts separately, Crosby, Stills & Nash even saw the three principals with their fingers on the faders when assisting Bill Halverson with the mix.

"There were parts that I mixed with maybe Stephen helping me, but a lot of it was a gang mix,” he confirms. "David, Stephen, Graham and I would be standing behind the console, each with our moves to make, and we'd make them and move them to two‑track. If one of us screwed up, we'd back up the tape and pick it up again, and then I'd edit the two‑track.”

A case of Halverson directing the mix and telling each man what he wanted him to do?

"I'd say it was the other way around. Still, did I try to keep us out of trouble technically and did I have a lot of input? Yes. They had a rule that whoever wrote the song would have the final say, and they really stuck to that. It's a wonderful rule.”

The opening track on the Crosby, Stills & Nash album, 'Suite: Judy Blue Eyes' turned out to be Stephen Stills' emotional outpouring about his crumbling relationship with folk singer‑songwriter Judy Collins, written over the course of several heart‑wrenching months. Issued as the second single following the release of 'Marrakesh Express' — which climbed to number 28 on the Billboard Hot 100 in August 1969 — this classic love song, backed with 'Long Time Gone', peaked at number 21 in October of that same year, while the ground-breaking album that spawned it reached number six on the Billboard 200.

"It's still a wonderful record,” Bill Halverson says, "and the warmth and fatness of the 15ips analogue make it hold up today, but I didn't have any preconceived ideas as to how it should sound. There were other guys they'd done demos with who really wanted to work on that project, but I ended up being CS&N's choice because they thought I'd have less influence on what they wanted to do. And in retrospect, I think they're right.”

Bill Halverson On Recording Cream

In March and October 1968, Bill Halverson part‑engineered the final two albums of another supergroup, Cream's Wheels Of Fire and Goodbye.

"On Goodbye, I really learned a lot about production working with Felix [Pappalardi]. The band members weren't really talking to each other, they'd already broken up, but they'd been persuaded to record one last album, and so Felix spent a lot of time going to the Beverly Hills Hotel and dragging them one by one back to the studio. On one of the first days, Eric [Clapton] was in there, fooling around by himself, and SIR provided a prototype Leslie foot pedal for him to try out. It was basically a little box with a button on it, and you could plug a guitar into the back as well as a cable that went to a Leslie speaker, and then power up both the box and the speaker. The button made the Leslie go slow‑speed or fast‑speed, so you could go back and forth.

"After the roadies hooked it up, Eric just sat there for hours, playing his guitar through that Leslie — I wish I recorded that. He was having a ball with it, and then, after the other two guys showed up, [Beatles roadie] Mal Evans suddenly walked in with George Harrison. So, then Eric and George were out there, playing through the Leslie for hours, and after Felix also had me set up the piano in the back of the room, little by little 'Badge' started to come out of that. I still have a rough mix of the bass, drums and piano, as well as George's rhythm guitar and Eric's [flanged bridge figure on] guitar through the Leslie, without the vocals or lead guitar.”

These were recorded sometime in late November or early December by Damon Lyon‑Shaw at IBC in London, where Clapton and Harrison wrote the lyrics, with the "swans that live in the park” line being contributed by, according to Harrison's later recollection, an "absolutely plastered” Ringo Starr. (Harrison himself was credited on the record as "L'Angelo Misterioso”.)

"That was the first time I had ever heard a guitar through a Leslie,” Bill Halverson continues with regard to the Wally Heider session, "so I was sitting there, unable to believe what I was hearing.

"By the evening, we had this track, but the kicker to the story is that, after everybody had left and I was packing up, I noticed the pedal was gone. The next day, when the roadies came in, I asked where it was, saying that SIR wanted it back. Nobody knew where it had gone, and so I then had to call SIR and explain what had happened. Now fast‑forward to a year later, when I was in England helping [Stephen] Stills to produce his first solo record, and who should walk through the door but Mal Evans and Ringo, who was going to play some drums. That night, we recorded a few songs, everybody had a good time, and after Ringo left, Mal drove me in his hot rod around London. While we were doing that, I said, 'Mal, back during the 'Badge' session, do you have any idea what might have happened to the pedal?' and he said, 'Yeah, George wanted it, so I put it under my jacket and took it back to England.' That may be how all of that Leslie guitar ended up on George's solo records. I don't know that for sure, but it seems too coincidental not to be the way it went down.”

Dubbed Drums?

Drummer Dallas Taylor arrived in the studio about a week after the nucleus of 'Suite: Judy Blue Eyes' had been recorded, and convinced that the timing was out near the beginning, he wanted to re‑cut the entire track with drums. That didn't happen.

"We ended up overdubbing his drums in the middle of the song,” recalls Bill Halverson, "and then Dallas finally talked Stephen into re‑cutting the front part with drums. So, we did that, put more vocals on there and edited it together, and I hated it. Eventually, we came to our senses, undid the edit and restored the song to its original place. However, the Dallas version did appear on the 1991 CS&N boxed set... and I still don't like it.”