Bob Marley and the Wailers were the first Jamaican musicians to achieve world stardom. Tracked in Kingston and finished in London by Island engineers Phill Brown and Tony Platt, their breakthrough album was a truly international recording.

Starting as a tape-op at Olympic Studios, London, in November 1967, Phill Brown was initially trained by such industry notables as Keith Grant, Glyn Johns and Eddie Kramer while working with artists like the Rolling Stones, the Small Faces, Traffic and Jimi Hendrix. Not a bad start. In 1970, after having built Toronto Sound, Canada's first 16-track studio, with his brother Terry, Brown then became a house engineer at the newly opened Island Records facility on Basing Street in Central London, where he initially worked with outside clients and stayed until going freelance in 1976. By then his credits included Harry Nilsson, Jeff Beck, Led Zeppelin, Robert Palmer and one Robert Nesta Marley, who as a member of the Wailers had first worked alongside Brown on the band's second Island release, the 1973 album Burnin'.

Released just six months after the Wailers' major-label debut Catch A Fire, the Burnin' album combined some old material originally produced by Lee 'Scratch' Perry back in 1968 with new compositions such as 'Get Up, Stand Up', 'Burnin' And Lootin' and 'I Shot The Sheriff'. These melded the funky reggae beat with lyrics about spirituality and the Jamaican struggle with poverty and violence. Accordingly, the record, featuring lead vocals by Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston, was essentially a call to arms, and 'I Shot The Sheriff' became its best-known song. As written and sung by Marley, the main protagonist admits that he did 'plant a seed' and gun down head-hunting Sheriff John Brown in self-defence, but pleads innocent to all charges of killing the deputy.

While Eric Clapton's relatively pale 1974 cover of the song would rise to the top of the US charts, the original did at least earn Marley worldwide fame and help his name precede the group's when Tosh and Livingston subsequently departed to pursue solo careers. Indeed, by far the most powerful version of 'I Shot The Sheriff' appeared on Bob Marley & the Wailers' superb Live! album in 1975, which Phill Brown captured at the Lyceum Ballroom in London, but it was the one recorded inside Basing Street's Studio Two that helped pave the way for Marley to transport his name, his music and his message to all corners of the globe.

Phill Brown at work in the early '70s.Photo: Ian Dickson / Redferns

Phill Brown at work in the early '70s.Photo: Ian Dickson / Redferns

Inside Basing Street

"In Studio Two, from '70 to '73, we had the first Helios desk, originally built for Olympic by Dick Swettenham," Brown recalls. "In fact, Island was all Helios, as was the mobile studio, the Stones' mobile and the Who's Ramport. The original Helios in Studio Two was 24 in and eight out, whereas when they brought in the next model in late '73, early '74, it was 32 in and 16 out. The 24-input desk was what we used for the Burnin' album, and it was brilliant. Its basic EQ was fantastic, fixed to 10k for the top end and 50Hz for the bass end, with four or five mid-range frequencies, and it had a beautiful sound. What's more, it had immediate mic amps — you plugged a mic in and there it was in front of the speakers instead of back somewhere in the distance.

"Helios, Cadac and Trident were all very similar during that era — just beautiful desks — yet they didn't have a lot of effects: two echo sends, I think, and maybe two foldbacks. That's all we had, so mixing was always about plugging in particular sounds from particular tracks. We didn't have aux sends where you could send every channel to all kind of things, and we therefore had to think ahead about what we were going to do. The Helios was a lovely desk for two people to operate in a mix environment on 16-track. Once it got to 24-track, things got hairy, but 16 was perfect.

"Along with the in-board EQ, I used the Urei 1176 for compression on the vocals or any other recordings that we did — they were pretty much the only compressors we had apart from some Helios ones — and EMT echo plates as well as the old Eventide digital delays. That was pretty much our classic setup during that era. A lot of what we did was down to miking technique and getting sounds in the room that we liked or we wanted. Rather than change it later, you had to be pretty close to what you wanted to have on the record.

"We used largely the same mics from session to session. I'd stick [AKG] D20s on guitar amps — I still do — and use 87s for backing vocals, 67s for lead vocals, D20s or FET 47s on amped keyboards... I guess we had our favourites, especially 87s and 67s during that era. Then again, I also know that Tony Platt and Richard Digby Smith — who worked at Island as an engineer — both fancied [Shure] 57s and the old [Electrovoice] RE20s. They weren't the conventional mics, but they were getting great results. And although I had my favorite mics for certain things, if you saw the mics used by the different engineers on the Bob Marley sessions, they weren't all the same."

The monitors in Studio Two were 15-inch Tannoy Red drivers inside Lockwood cabinets suspended from the ceiling, while the tape machines were a 3M 24-track, 3M 16-track and an Ampex eight-track that was used to make transfers.

"The desk, tape machines and speakers were all housed inside a pretty small control room — maybe 15 foot square, 20 foot square — where the engineer would sit right up against the wall with the desk in front of him. It would be very un-hip today. And the studio itself would hold, at a push, 15 musicians if it was a string session, or otherwise a five- or six-piece band. It was an easy room to work, whereas upstairs [Studio One] could accommodate a 60-piece line-up and was a much harder beast to manage. It needed either acoustic intruments, including strings, or a heavy rock band to make it work. On the other hand, the Studio Two control room was fantastically accurate and it became a very serious mixing environment before the computer-aided era."

Across The Atlantic

Prior to the sessions, the Wailers recorded their songs — including new versions of numbers such as 'Put It On', 'Small Axe' and 'Duppy Conqueror' that had previously been produced by 'Scratch' Perry — at Marley's own Tuff Gong eight-track facility in Kingston, Jamaica. The tapes were then transported to Basing Street and transferred to 16-track in preparation for overdubs of extra guitars, keyboards and vocals, as well as the mix. This was the procedure that had already been utilised for the Catch A Fire album.

Photo: Ian Dickson / Redferns

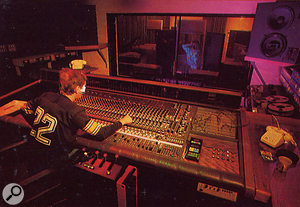

Photo: Ian Dickson / Redferns Basing Street Studios as it appeared in the late '70s: by this time, Studio One (left) and Studio Two (right) had both been refitted with MCI 500-series desks. Photo: Ian Dickson / Redferns"The tapes that they brought over actually contained seven tracks of recordings because track six didn't work," says Brown. "Everything was mono: two tracks of drums — the bass drum and a kit track — a track of bass guitar, a track of Hammond organ, a track of guitar, two tracks of vocals... very basic, but it was decent quality. We'd add maybe an extra guitar, an extra keyboard and try new vocals, but we didn't change very much in terms of the original vibe. We'd listen to the tracks as we transferred them and try to get the sounds to sit in that type of space rather than bring them to a completely different kind of thing. What was done where didn't really come into it, although I for one was definitely trying to make the record more Kingston than Notting Hill Gate."

Basing Street Studios as it appeared in the late '70s: by this time, Studio One (left) and Studio Two (right) had both been refitted with MCI 500-series desks. Photo: Ian Dickson / Redferns"The tapes that they brought over actually contained seven tracks of recordings because track six didn't work," says Brown. "Everything was mono: two tracks of drums — the bass drum and a kit track — a track of bass guitar, a track of Hammond organ, a track of guitar, two tracks of vocals... very basic, but it was decent quality. We'd add maybe an extra guitar, an extra keyboard and try new vocals, but we didn't change very much in terms of the original vibe. We'd listen to the tracks as we transferred them and try to get the sounds to sit in that type of space rather than bring them to a completely different kind of thing. What was done where didn't really come into it, although I for one was definitely trying to make the record more Kingston than Notting Hill Gate."

Phill Brown was, thanks to some prior work with Trojan and Jimmy Cliff, "kind of aware of reggae" when he first became involved with the Burnin' sessions. However, by his own admission, he also wasn't a huge fan of the genre and he didn't know a lot about it. For him, it was simply a case of editing and overdubbing the material that he was being presented with.

"In sonic terms I was given a huge rein," he says. "For instance, when I was setting up the mix for the classic Live! album, Blackwell would just say 'Give me more audience,' and I was then very much left to do what I'd do. That entire record was mixed in six hours. It was a different era. If I was mixing it today there'd be a lot more people saying 'More bass, more this, more that...' Back then, everything was done really fast and Blackwell seemed to trust the people he had around him. The final call was always Chris's decision, but in those days it wasn't so much about the technology. It was much more important to capture the atmosphere, the energy and the vibe of the track. Especially with reggae and Bob Marley songs — we could have made them very schmaltzy by smoothing them out, but that's not what it was about, and a lot of the records nowadays are very smooth by comparison.

"I'd heard some of the Wailers' earlier material, which was more roots reggae — the slower, kind of sleazier stuff — and we did actually speed things up. When we mixed, we'd speed up the 24-track a little bit to make the music more accessible. That was really a Chris Blackwell decision, setting it up for a Western audience; an English, European and eventually American audience. Real reggae was much slower in a sense, more roots sleaze, and we were just making it a little bit more commercial. That's why the overdubs were done."

Bringing Reggae To The World

Island Records boss Chris Blackwell, who co-produced most of Bob Marley's '70s output.Photo: Ian Dickson / RedfernsFew people did more to bring Jamaican music to a wider public than Island Records boss Chris Blackwell, who co-produced most of Bob Marley's '70s output along with lots of other reggae classics. "Blackwell was one of those guys who was very good at putting like-minded people together in the studio, and he was always there with encouragement: 'Yeah, this is good. Let's move on to this,' or 'Oh yeah, that's feeling great. Why not try this?'" explains Phill Brown. "However, he wasn't producing the record in the sense of a modern pop production where somebody would be there to direct every moment. He came and went. And when he went, we knew what we all had to do, so if we were in the middle of vocals and Chris popped out for half an hour, we'd just carry on and Bob, the musicians and I would make decisions like 'Yeah, that feels good. Let's go with that verse.'

Island Records boss Chris Blackwell, who co-produced most of Bob Marley's '70s output.Photo: Ian Dickson / RedfernsFew people did more to bring Jamaican music to a wider public than Island Records boss Chris Blackwell, who co-produced most of Bob Marley's '70s output along with lots of other reggae classics. "Blackwell was one of those guys who was very good at putting like-minded people together in the studio, and he was always there with encouragement: 'Yeah, this is good. Let's move on to this,' or 'Oh yeah, that's feeling great. Why not try this?'" explains Phill Brown. "However, he wasn't producing the record in the sense of a modern pop production where somebody would be there to direct every moment. He came and went. And when he went, we knew what we all had to do, so if we were in the middle of vocals and Chris popped out for half an hour, we'd just carry on and Bob, the musicians and I would make decisions like 'Yeah, that feels good. Let's go with that verse.'

"Chris was really coming at things from both a commercial and a musical angle. I've known him a long time and I guess his greatest love is Jamaican music and that whole approach. I mean, he's given a lot of people a huge number of chances — he's been one of the great mavericks of the music business. And with all of us back then, he'd allow us to do our thing. He was making commerical decisions, yes, in terms of speeding things up or asking for more audience in the live mix, and they were well judged, but these were all based on a music that he really loved.

"Okay, so the real die-hard reggae enthusiasts of that era may have been really pissed off because certain tracks were sped up — there was an article in the NME where the guy figured out that two versions of the same piece of music were 13 seconds different in length and seemed to be in a different pitch. However, it wasn't the Bob Dylan as Judas thing, and at the time it appeared that the Wailers were willing partners in all this. My memory is of everyone being there during the overdubs — I'm not sure that was the case when we were mixing. That was more down to just Chris and I. But I don't recall anyone complaining. It was later on that you'd hear through the grapevine that maybe one of the guys wasn't pleased. At the time it wasn't a problem, it was like 'Let's tweak that up by a few percent.'"

Editing & Overdubs

In the case of 'I Shot The Sheriff', there were three versions on the eight-track that were all copied to 16-track.

"I remember Rabbit [keyboard player John Bundrick] came in and played either electric piano or a Wurlitzer kind of overdub part that was DI'd," Brown recalls. "Everything was very immediate. If you listen to those records, there's not a lot of room sound, as such; just great in-your-face sounds. If it was acoustic piano, we would mic it up with a couple of [Neumann] 87s and record it fairly good quality. However, most of the overdubs back then were done with Wurlis, Clavinets, electric pianos — stuff that was much more DI'd, amped up and a little more aggressive. And when the session guys came in we would have them play across three, four, five tracks that we had ideas for rather than work on one track at a time and finish it.

Basing Street Studios is now SARM West.Photo: Ian Dickson / Redferns

Basing Street Studios is now SARM West.Photo: Ian Dickson / Redferns

"So, in terms of hard sessions — sessions being three hours — we would probably copy everything from eight-track to 16-track in a three-hour session and then we would bring in musicians for a three-hour session. Maybe somebody like Rabbit would be there for two of those sessions — be there for six hours or an entire evening — but basically the musicians would come in and we would run the songs by them and see what they thought. Chris would point out the direction in which we might want to go, and we would just record and then off they would go after they'd done their three hours or six hours or whatever. You see, there were specific ideas and plans, but they weren't really pinned down. It was more a case of 'OK, let's get this guy in. He'll be good for this, and while he's here why don't you try him on that?'

"There would have been a pass or two of the keyboards on 'I Shot The Sheriff', and we may then have tried out the odd extra guitar part before moving on to the vocals. All of the songs arrived with vocals already on there, but Burnin' was the last time that the whole band was present in London — after that, some of them didn't travel and the line-up changed — and so we recorded a track of backing vocals as well as a new lead vocal by Bob Marley. A [Neumann] 67 or 87 on vocals was pretty much the norm of the day, so that's what I used for Bob, and everyone else went through an 87. Again, it was a case of just capturing the moment and capturing the vibe of the guys rather than the finesse of a modern recording.

"The small room in Studio Two was very live, so we had a couple of screens up with an 87 just to make it a little bit more cosy. The control room was on the other side of a window, so visually there was very easy contact, and we just recorded with the meters to the 16-track machine. Of course, at the time of those sessions the Wailers weren't as big as they would become, but my main memory and image of that era is of these guys, these quite hard characters, who had a real attitude. Obviously, they were kind of street guys — not sweet locals, but really cool characters who were writing music that really meant something, and when it came to the vocals Bob got out there and just kind of did what he needed to do.

Bob Marley's studio, Tuff Gong, is still an active and popular recording venue in Kingston. Photo: Ian Dickson / Redferns

Bob Marley's studio, Tuff Gong, is still an active and popular recording venue in Kingston. Photo: Ian Dickson / Redferns

"He sang, and it was very easy for him to do stuff, so we didn't do a lot of takes. In fact, we never did in those days. There were probably a couple of passes, a couple of versions and one would be chosen. It was not a long process. Everything was happening quite fast. Bob very much knew what he was after, and so did everyone else because he was not so much the leader of the band in terms of telling them what to do. They were all aware of what they were doing and he knew exactly what he needed to do.

"Comping did take place, but this was before people got heavily into that kind of thing. I mean, it was done during the early '70s, but you were more likely to have had two takes of vocal and switch between them in the mix according to what you wanted. We hadn't really got to the point of doing three, four, five, six vocals and mixing down. In fact, we were always concerned about frequencies and sound, and so we never wanted to mix down too much because of the loss in quality. This would later result in better tape machines becoming quite common, but back then, if there were two vocals by Bob Marley, it was quite likely that they'd get switched in the mix rather than bounced beforehand."

Following the keyboard and vocal overdubs, and prior to Aston Barrett recording more lead guitar, some 16-track, two-inch editing had to take place. After all, there were three versions of 'I Shot The Sheriff' on tape and Blackwell wanted to use the first part of one version spliced together with the second part of another version. Thereafter, the aforementioned guitar was overdubbed and the song was mixed along with some other tracks.

The Party Atmosphere

The idea that an album had to be recorded by a single engineer had yet to take hold at Island Records in the '70s. "Tony Platt and I both engineered the sessions at Basing Street — we were house engineers, and due to the way that studios worked in those days one of us would be on the session one week and the other would be on it the next. That meant we never necessarily followed projects through from start to finish, and while Tony and I were the two guys on the Bob Marley sessions at that point, if we weren't around there was always Phil Ault who also did some work with Bob. So it was very much a case of who was available for a particular session.

"During that era it was a bit like a long party at Island. We were all good mates, some of us lived together, and Tony was even the best man at my wedding. We were a very close bunch of guys, and so when I replaced Tony on a session he would fill me in by saying 'We've been doing keyboards this week with Rabbit [John Bundrick],' or 'Bob's coming in to do vocals.' We always knew what was going on."

At The Mix

"We would maybe mix three songs a day," Brown remarks. "Again, it was a fairly fast turnaround, and Tony might well have mixed the songs again the following week. It was that kind of approach. Chris would leave me to set something up and people would be floating around all the time; dancing and spliffing and partying. Chris would keep checking in, and once he heard something that he thought was what he wanted, he'd say 'OK'. If something needed to be guided into shape, he'd sit down with me and say 'Let's try a bit more of this, try that,' but most of the time people were floating about, listening and having a good time, and if something felt really good we'd put it down. It was much more relaxed than it probably would be today.

"Since the tracks had been honestly recorded, with a pretty clean, straight sound on the tape machine, the effects that we used — and they were very limited during that era — were just an EMT echo plate, maybe a bit of spring reverb, some Urei compression, perhaps a little bit of delay and ADT on the backing vocals, all done in the mixing environment. Looking back, it's amazing that we made those records with such limited gear. It really was very basic, and yet it all sounded great even if manual mixing brought its own quirks to the table.

Photo: Ian Dickson / Redferns"We had to be creative, and if we wanted to have something that was really pretty wild — something that would be easy today to dial up on some machine — we had to work out how to do it. If we wanted the sound of somebody in a church, we basically had to go there and record them. We couldn't fake it. And in the studio we fed a lot of stuff back through Leslie speakers and distorted stuff through amps. We had to move things on. In fact, we could distort the desk very easily — that was a great device that we used at times. You could get a great fuzz guitar out of the Helios desk by overdriving the line, which you can't really do on modern desks because they just take too much input. These desks didn't, so there were kind of quirks that you could work with."

Photo: Ian Dickson / Redferns"We had to be creative, and if we wanted to have something that was really pretty wild — something that would be easy today to dial up on some machine — we had to work out how to do it. If we wanted the sound of somebody in a church, we basically had to go there and record them. We couldn't fake it. And in the studio we fed a lot of stuff back through Leslie speakers and distorted stuff through amps. We had to move things on. In fact, we could distort the desk very easily — that was a great device that we used at times. You could get a great fuzz guitar out of the Helios desk by overdriving the line, which you can't really do on modern desks because they just take too much input. These desks didn't, so there were kind of quirks that you could work with."

The overdubs for the Burnin' album were completed within three or four days, and a similar amount of time was then spent on the mix.

"There was the odd spin, the odd effect or a bit of phasing to push home a particular point, but by and large the Wailers records consisted of all solid sounds," asserts Phill Brown, whose other engineering and/or production credits include Paul Kossoff, Steve Winwood, Talk Talk, Dido and Santana. "There was nothing trippy or psychedelic or anything like what 'Scratch' Perry was doing with dub reggae. It was like recording a rock band. There were five different instruments, a handful of tracks, and there it was; solid, really cool, it had the vibe, and there was no trickery.

"You can bring up any of those tracks and the attitude of the playing is fantastic. We were just adding a few extra bits to that and giving it a little bit of gloss, I guess; giving it a bit of an English sound and making it something more than had it just been finished off in Jamaica. And while some people may have preferred the Wailers' sound when they were with 'Scratch' Perry, Bob stuck with Chris Blackwell through many, many albums and Chris did him a lot of good. At least he reached more people thanks to that approach.

"There was this real honesty in all of the stuff that Bob Marley did. It was really what he was about. That was him. And while a lot of people may have made money off the back of it all, it was his music and his message that really came through. That's why he was such an energy and a force. You felt that when he was wandering around the studio. Even then, before he was massively famous, you felt that this guy had something."