Recording Sinéad O'Connor's breakthrough hit was easy in some ways, but difficult in others — for example, all compression was forbidden...

Photo: Michel Linssen/Redferns

Photo: Michel Linssen/Redferns

Towards the end of the award‑winning video that was shot to promote her 1990 international hit single 'Nothing Compares 2 U', tears run down each of Sinéad O'Connor's cheeks as she sings, "All the flowers that you planted, Mama, in the back yard, all died when you went away.” These, she'd later explain on VH1's 100 Greatest Songs of the '90s, were prompted by thoughts of the complicated relationship that she had shared with her late mother.

Not that O'Connor had written this number about longing for a lost love. Instead, Prince had composed it for the Family, a band signed to his Paisley Park label, inspired by a member who had recently split up with his girlfriend and recorded by the funk outfit for their eponymous 1985 album. Identifying with the lyrics, O'Connor imbued the song with a strikingly authentic, heartfelt intensity that, aided by the equally stark and powerful video, transported it to the top of the charts in no less than 15 countries, including Britain and America, where it was certified platinum after four weeks as the number one single on the Billboard Hot 100.

"I actually think the intensity of Sinéad's performance came from the breakup of her latest relationship,” opines Chris Birkett, who co-produced and engineered the track as well as the accompanying, Grammy Award-winning album, I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got, which topped the Billboard 200 for six weeks and sold seven million copies worldwide. "She had been dating her manager, Fachtna O'Ceallaigh, who's a really good guy and had been instrumental in getting her deal with Ensign Records. However, their relationship had gone pear-shaped and they were in the process of breaking up when we recorded 'Nothing Compares 2 U', so that's probably why she did such a good vocal. She came into the studio, did it in one take, double-tracked it straight away and it was perfect because she was totally into the song. It mirrored her situation.”

At the time, there were rumours that O'Connor was dating Prince. That was, when another possible suitor wasn't paying her daily visits.

"Every day, this guy in sunglasses used to come into the studio and sit at the back of the control room,” Birkett recalls. "He never introduced himself and I wondered who the hell he was, until I finally asked his name and he responded, 'Peter Gabriel'. He and Sinéad appeared to be spending a lot of time together, so who knows? I still think she was crying about Fachtna O'Ceallaigh, but maybe she was crying about Peter Gabriel or she could even have been crying about Prince. Whoever it was, she was upset about someone and that's why she put everything into the song as well as into the video. It was the video that really broke the song, because the BBC dropped it and it was on its way out of the charts when the video came out and everything went ballistic.”

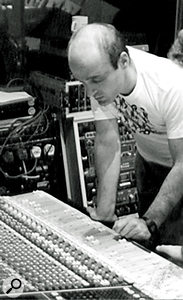

Chris Birkett

Chris Birkett looking thoughtful at the desk in Eden Studios.

Chris Birkett looking thoughtful at the desk in Eden Studios.

Virtually an orphan after his mother walked out on the family home when he was just four years old, Birkett himself was no stranger to feelings of loneliness. Music was his escape from a troubled childhood and, harbouring a burning desire to play the guitar, he built one from old pieces of wood and banjo strings when he was eight. "It sounded like a Japanese koto, but at least it worked and enabled me to make music,” he recalls.

Left-handed, Birkett taught himself to play the instrument, and by 1965, when he was 12, he had saved enough money to purchase a right-handed electric guitar that he strung the other way around. Two years later, he began playing with his first band, Friends Of Fernburg. Nevertheless, still unhappy with his home life while studying electronics, he ran away at age 19. He was working the night shift at a petrol station while sleeping on the London streets when, in 1974, he landed an 18-month gig touring German NATO bases with an R&B band named Montana Red Dog. This was in support of Memphis artists such as Rufus Thomas, Ann Peebles, Jean Knight and King Floyd, and on Birkett's return to London he then joined the Love Affair, who had enjoyed a UK number one single a decade earlier with 'Everlasting Love'.

"While I was in Love Affair, we spent three months playing at a club in Guernsey, which was then a tax haven, and Led Zeppelin were there for the same reason,” he recalls. "Every night, they would visit the club and jam with us. So, there I was, alongside Jimmy Page, John Bonham and the rest of the band, playing my 1959 Fender Stratocaster which I had modified with an internal preamp to boost the power for solos. This probably made it the first active guitar...”

Next, in 1977, came a stint with a rock outfit named Omaha Sheriff, who were signed to Tony Visconti's Good Earth label and subsequently recorded two albums that were produced by him. Watching Visconti in action was what turned Birkett onto the idea of studio-based production and engineering. Armed with his electronics degree, he soon landed a job constructing the Tapestry facility owned by his friend John Kongos in Southwest London.

"After I finished building the studio, John didn't have an engineer,” Birkett states. "So, he asked if I'd like to do it, I accepted and the first three months were hell. In fact, I recorded my first brass session on the wrong side of the tape. It was hairy, to say the least, but I learned really quickly, I got my own clientele and the first hit record I engineered and mixed was 'Geno' by Dexy's Midnight Runners.”

That was in 1980. Two years later, with a little more studio experience under his belt, Chris Birkett launched his own CB Sound facility in Kingston, just south of London, and during the next several years, while splitting time between there and Tapestry, he worked with anyone from Thomas Dolby, Mel Brooks and Alison Moyet to Five Star, the Kane Gang and Talking Heads. Birkett's mix of '(Nothing But) Flowers', which ended up on the last band's final album Naked, was done in 1987, and that same year he also remixed a couple of tracks that were issued as singles from Sinéad O'Connor's debut LP The Lion & The Cobra: 'Mandinka' and 'I Want Your (Hands On Me)'. These, in turn, led to his co‑producing and engineering 'Nothing Compares 2 U' after he received a call from Ensign Records' founder Nigel Grainge to replace the track's original producer, Nellee Hooper.

The Background

Chris Birkett playing live at Les Déchargeurs in Paris.

Chris Birkett playing live at Les Déchargeurs in Paris.

"I had a meeting with Fachtna O'Ceallaigh in a car parked outside a studio and he played me the song,” Birkett recalls. "Nellee Hooper had been involved for two days until he and Sinéad had a bust-up and she walked out. At that point, there was a drum loop, some strings and backing vocals, and I thought the song was really good, but it needed rearranging, so that's what we set about doing.”

The man who was largely responsible for the backing track was drummer and Japanese acid jazz virtuoso Gota Yashiki. Previously he had played with the Tokyo-based reggae/dub outfit Mute Beat and, together with fellow band member Kazufumi Kodama, formed the duo Kodama & Gota. During the late-'80s, before drumming on Simply Red's 1991 Stars album and the group's subsequent world tour, Yashiki worked in London with artists that included Soul II Soul, Seal and Sinéad O'Connor, and it was his programmed string arrangement on 'Nothing Compares 2 U' that now prompts Chris Birkett to describe him as "a genius”.

"He was so talented and creative,” he says. "He understood things really, really quickly — a totally intuitive musician.”

"I had worked with Nellee Hooper on Soul II Soul's record, arranging, programming and also playing the drums,” Gota Yashiki remarks. "That project went really well, so when Nellee started working with Sinéad O'Connor on 'Nothing Compares 2 U', he asked me to join them and again do the arranging and programming. The engineer was a female named Arabella Rodriguez, who had also recorded and mixed Soul II Soul.

"At first, we did pre-production at Nellee's house, where I did most of my work using an Atari with Notator software and an Akai S1100 sampler. Then we began recording at Pink Floyd's studio, Britannia Row, where I did some overdubs — a little drums and playing keyboards for a cello part. The track was really slow, and the bass drum and snare drum sounded great, but the programmed hi-hat just wasn't working. So I asked if a hi-hat and cymbals could be hired, and I played those live. Then the cello part still wasn't gelling together, so I overdubbed that at Britannia Row using the Akai sampler with a keyboard.

"I wanted to be really sure that everything felt right, and this meant the strings had to sound natural, which I think they do. I played all of the parts, we finished the backing track and Sinéad was working on the vocal when something went wrong between her and Nellee. They had an argument — I don't know what it was about — and suddenly he quit the project.

"A few weeks later, she was in a mix session at another studio and coincidentally I was next door. When she found out I was there, she knocked on the door and said, 'Gota, can you check out the track? We've just finished mixing it.' So that's what I did, and it sounded like all of the work I had done on the track was still there.”

Hands-on Vocal Mixing

Following the Britannia Row sessions, Chris Birkett recorded the remaining parts for 'Nothing Compares 2 U' piecemeal at Westside Studios on an SSL E Series console and analogue Studer 24-track machine with Dolby SR.

"I did some rearranging by working on the timing of the drums,” Birkett explains, "and we also recorded some simple downbeat chords on the piano before taking care of the lead vocal.

"Before the advent of digital, I would normally spend days and days on a vocal, tuning up and dealing with the timing. That's what happened when I worked with Mel Brooks — each time, I spent about a week getting him in time on 'To Be Or Not To Be' and 'It's Good To Be The King' because he couldn't rap. Being a fanatic about vocals, I used to do everything by ear back then. However, Sinéad came in and first take it was all there; I didn't have to touch it. She sang it straight off and then said, 'I want to double-track it.' So, that's what she did and it was perfect. I was really surprised. I had never seen anybody double-track something so perfectly that there was no need to then drop-in and fix stuff. It was as if this was meant to happen.

"The only difficulty we had took place during what should have been a relatively easy mix on the SSL at Eden Studios, because there wasn't much instrumentation. For some reason, Sinéad hated compression, and when I'd come in each morning there would be a piece of white A4 paper on the console saying 'NO FUCKING COMPRESSORS!' The problem was, she had a reverse mic technique. When most people sing loud, they back off the mic, but she used to do the opposite — she would stand away from the mic when singing quietly and then scream right into it. That was probably her idea of getting a more powerful vocal, but I can tell you it was bloody hell to record and mix that without a compressor, a limiter or anything that touched the signal.

"Some of it was distorted because she was yelling into the mic when the gain was up to try to capture her quiet vocals, and so I spent hours and hours using the SSL's automation on every single syllable to make it audible, and I also had to ride the EQ during the mix to take out the high-mids because the mic was overloading and sounding awful. It's not like now when I'm working with Pro Tools and Logic and can automate anything — it's fantastic. Back then, I had to do it in real time, riding the EQ by hand when I was running the final mix, and that was tricky.

"With Sinéad and most other artists, I use an AKG C 414B-ULS for vocals. It's one of my favourite mics because it can take a lot of dynamics, whereas if I used a Neumann her vocal would have been distorted all the way through, thanks to her terrible mic technique. Neumanns break up very easily, but the 414 can take a lot of punishment and still be clear with practically no background noise. I've used it on Alison Moyet, Buffy Saint-Marie and virtually everyone else I've worked with.”

I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got

Meanwhile, for Chris Birkett, the vocal nightmare continued throughout the six‑week-long sessions for the I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got album which also took place at Eden and his own CB Sound studios.

"Sinéad wouldn't allow any form of automatic level control,” he confirms. "When I asked her why, she said she thought it was fake. She wanted her vocal to be more natural. And that would have been fine had she not used that reverse mic technique. She'd probably picked that up on-stage, trying to project, but it was the complete opposite of what most people do.

"Other than that, the album was extremely easy to make. The main thing I recall was that Sinéad was always tired, so we worked really short days. She'd come in at, like, two in the afternoon and go home at six that evening, but things still moved along very quickly. The musicians would come in and lay down their parts, and I don't remember being tired or stressed at all.”

While Marco Pirroni contributed electric guitar, David Munday played acoustic guitar and piano, Andy Rourke was on acoustic guitar and bass, Jah Wobble also played bass, Steve Wickham played the fiddle and the drums were handled by O'Connor's sometimes‑co‑producer and former husband, John Reynolds, with whom she'd had her first child.

"I don't subscribe to the anal school of record production, where you get into every little facet and take forever to do anything,” continues Chris Birkett, whose other credits have included projects with, among others, the Pogues, Steve Earle and Siedah Garrett, as well with Cry Cisco whose 1988 UK club hit 'Afro Dizzy Act' he co-wrote, co-produced and performed on. "I did the Fairlight programming for Def Leppard's Pyromania album and it was just murder, sitting for a whole week listening to the hi-hat against the click. I can't stand that. I'm an intuitive producer and I never mess around with EQ when I'm recording anybody; I just capture everything dry and natural and then I sort it out later.

"Sinéad liked working with me because I wasn't egocentric like most producers. I believe that real creation comes from the divine, that there's a flow of energy from the divine to the material, and that you have to just let it happen without getting in the way or trying to over-think things. You can work on things later, but the editing process should still never interfere with the creative process. I just let the creative process happen and try to capture it, and that meant Sinéad could manifest whatever she wanted. When it came to the vocals, some producers would have said, 'Forget it, I'm not going to record you without a compressor,' but I said, 'OK, let's try it,' because I wanted her to feel comfortable. I wasn't about to go all egocentric on her and try to control and steer her.”

Unfortunately for Birkett, this giving, easy-going attitude wasn't exactly reciprocated.

"At that stage, not having a manager to take care of me, I was doing a lot of work that I didn't get the proper credit for,” he says. "So the secretary at Ensign Records pushed for me to have a co-production contract for 'Nothing Compares 2 U' as well as for the album, and I earned royalties on that basis. Yet Sinéad had this thing in her head about being credited as the sole producer, and although it was crazy, that's what happened.”

Ditto Gota Yashiki. The only people credited for the string arrangements on I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got were conductor Nick Ingman, who conducted live orchestral sessions at London's Lansdowne Studios... and Sinéad O'Connor.

Separate Ways

When, in 1991, Chris Birkett co‑produced another Sinéad O'Connor single, 'My Special Child', he did receive the appropriate credit. However, her amenable attitude didn't last.

"She asked me to work on her next album [eventually titled Am I Not Your Girl?]," Birkett recalls. "This would feature her covering mostly jazz standards, and so I said, 'Yeah, I'm happy to do that, but this time I insist that you credit me as co-producer.' Well, she got really weird about that, we went our separate ways and I haven't seen her since. The same thing happened when I was asked to do a Soul II Soul album — I'd be engineering, programming and doing all of this work, but they didn't want to give me a production contract or any credit. So, I told them to forget it. By that time, I'd really had enough of being used in that way.”

Not that Sinéad considered her own behaviour to be in any way unreasonable.

"I don't do things in order to achieve any particular image or to achieve record sales or any of that stuff,” she told an interviewer for the TV show Rapido in 1990, at around the time of her second album's release. "I just do what comes naturally to me, and if I think I've been an arsehole I say so.”

In their review, Rolling Stone asserted that "I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got is less about O'Connor's ambitions than the cost of those ambitions, and in almost every regard, it is an even better record than her first. The album seems the work of a transformed woman — someone who has put aside much of the anger and confusion that fuelled her earlier songs and has found a hard-earned measure of spiritual happiness... Indeed, if I Do Not Want What I Haven't Got is a work about spirit, it is a spirit that is fierce and caustic.”

It was in this spirit that, when the record won the Grammy for Best Alternative Album, O'Connor boycotted the ceremony and refused the award as a protest against the event's "extreme commercialism”. She was the first artist to do so.

A Bit On The Side

Following the worldwide success of 'Nothing Compares 2 U', Chris Birkett was in so much demand at his studio, CB Sound, that he had little time to spare for his young son and daughter. "When I heard them calling my sound engineer 'Dad' I thought 'enough is enough',” he recalls.

In 1993, after releasing his own album, Men From The Sky, and donating a track from this, 'Where Do We Go From Here', to the One Voice, One Love charity record that also featured acts such as U2, Dire Straits, Seal and Peter Gabriel, Birkett purchased a 32-room château in Bordeaux, France. He subsequently used this to house a studio, Château Richard, where he worked with the likes of Bob Geldof and the Buena Vista Social Club.

Fast-forward to 2006, and in the wake of getting divorced, Birkett relocated to Paris. Three years later, he recorded his second album, Freedom, which, among its list of guest artists, features one Tony Visconti on bass. While promoting this, he is involved in two more studio ventures: one, opened recently in downtown Toronto, Canada, with two Canadian partners, is a hi-tech Pro Tools-based facility called Chris Birkett Productions; the other, launching soon in Kauai, Hawaii, is the state-of-the-art Raku Media, which will have its own record label.

"It's all happening,” he says. "I plan to base myself in Canada and the US, and right now, having written all of the songs, I'm working on my next album. This will be higher energy than the chill-out, Leonard Cohen-type feel of Freedom and it will blend electronic sounds with natural, world music instruments.”