The Bangles. Left to right: Vicki Peterson, Susanna Hoffs, Debbi Peterson, Michael Steele.Photo: Lester Cohen

The Bangles. Left to right: Vicki Peterson, Susanna Hoffs, Debbi Peterson, Michael Steele.Photo: Lester Cohen

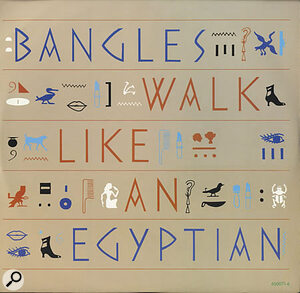

‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ was a huge hit for the Bangles, but it all started with a demo mix‑up and some very unusual percussion.

One of the biggest hits of the ’80s (and a staple of rock radio ever since), the Bangles’ ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ was instantly everywhere upon its initial release in 1986, topping the US singles charts and reaching number three in the UK. But behind its driving beat, quirky hooks and sunshiny indie pop vibe lay the difficult and fractious story of its creation. At the time, it may have been the commercial high watermark for the Bangles — Susanna Hoffs (vocals/rhythm guitar), Vicki Peterson (vocals/lead guitar), Debbi Peterson (drums/vocals) and Michael Steele (bass/vocals) — but in truth some members of the band hated the track.

Ahead of the making of the Bangles’ second album, Different Light, Prince had already offered up a song he’d written, ‘Manic Monday’, for the band to record. ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ had similarly been written by an outsider, Liam Sternberg of Akron, Ohio band Jane Aire & The Belvederes, who’d branched out as a songwriter for other artists. By the time it was brought to the Bangles, the song had already been rejected by two one‑off novelty hit singers, Tony ‘Mickey’ Basil and Lene ‘Lucky Number’ Lovich.

Vicki Peterson later remembered, “David Kahne, our producer at the time, showed up at rehearsal with a tape of a demo of the song, sung with a droll charm by [US singer] Marti Jones. I realised that we were never gonna write a song like that and there was nothing remotely like it on our album so far and I agreed to try it in the studio. We had a sing‑off for the verses, with Kahne as head judge. Don’t know that I’d ever do it that way again.”

“There was always some tension,” David Kahne says today. “But that’s not uncommon when producing a band. There’s usually tension between the band members and there was in the Bangles.”

To complicate matters, as well as being the band’s producer, Kahne was also their A&R man at Columbia Records. “I was critical,” he admits. “So, if somebody is doing something that I don’t think works, I wait until I can say, ‘Why don’t you try this?’ Y’know, any time you’re criticising somebody, you have to be careful. I always wondered if I hadn’t been at the label if they would’ve decided to get rid of me.”

Chance Encounter

David Kahne had followed a twisty path to this point in 1986 where he was both a record producer and A&R man. Originally a high school English teacher, who played in bands in the evenings and at weekends, he’d started writing and demo’ing songs with one of his students and then landed a deal with Capitol Records.

Together, the pair made two albums in the mid‑’70s under the name of Voudouris & Kahne. “Two albums that are a little embarrassing at times,” he confesses. “When I heard Aja by Steely Dan, I realised, ‘Oh, that’s what I was going for.’ But if you heard the music that we did, you would say, ‘Yeah, you didn’t get there.’ But I didn’t think the producers were good and I couldn’t figure out why.

“So, I heard myself on the radio one day — the one DJ that played the one song the one time — and I thought, ‘I’m not good enough.’ And I stopped and I got a job at a studio in San Francisco, answering phones, to learn how to run the gear. Cause I thought, ‘Well, I wanna be a producer. I’m as good as those guys.’”

Using all the studio downtime that he could get, Kahne began to gain valuable recording experience. First of all, employed at Wally Heider Studios in San Francisco, and later moving to punk/new wave label 415 Records’ studio The Automatt, he started recording various Californian bands such as Rank & File and Pearl Harbor & The Explosions. “A couple of them took off,” he remembers, “and that’s how I got my job at Columbia.”

Before that, Kahne had already met the Bangles in 1982 when the LA‑based band travelled up to San Francisco to promote their self‑titled debut EP. He and the group ended up recording a song together, which was heard by Columbia A&R man Peter Jay Philbin. “I went to Columbia right as he was signing them,” Kahne recalls, “and he signed them partly with the idea that I would produce them.”

The Bangles meanwhile had built a reputation for themselves on the Los Angeles gig scene with their alternative take on chiming ’60s power pop. It was a sound that was polished by Kahne on their 1984 debut album, All Over The Place, which produced the singles ‘Hero Takes A Fall’ and ‘Going Down To Liverpool’.

“They all wanted to sing and be lead singers,” Kahne says. “They used to share. They would come in and it would be, ‘OK, now it’s Debbi’s turn to sing.’ I think a few people had noticed that the big songs were all sung by Sue.

“I never had any problem with Sue,” he adds, “it was the Peterson sisters. Mostly the drummer. And I bring that up because it relates to ‘Egyptian’.”

Kahne was going through tapes of songs he’d requested from publishing companies when he first heard the demo of ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ on what turned out to be a mislabelled cassette.

“The cassette said ‘Rock & Roll Nightmare’,” he recalls. “And I goes, ‘Huh, well I don’t like that title.’ But anyway, I listened to it, and I hear [sings main riff] ‘Doot‑doot‑doo‑doo’. So, I called the publisher and I told her there was this song about an Egyptian on it and she said, ‘Oh, they put the wrong song on there. I’ll send you it over.’ I go, ‘No no, I like this one.’ That weird, non‑linear stuff happens so often doing A&R and the trick is to know if this is the good mistake.

“It sounded good,” he remembers about the ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ demo. “It was quirky and odd. I wanted to get another single because we had ‘Manic Monday’ and I didn’t feel like there was a strong enough follow‑up. There was a song called ‘If She Knew What She Wants’, which I love. But I didn’t feel if ‘Manic Monday’ worked that it was the best thing to come right after.”

Kahne doesn’t remember the band seriously considering ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ at first. “It didn’t even get to rehearsal,” he says. “They just didn’t want to record it. It was Debbi’s turn to sing a song. She didn’t want to do it, she thought it was a dumb song. And I said, ‘Well, I wanna do this, we could at least try it. Y’know, it’s your turn to sing a song. Do you wanna not sing a song? [laughs]’. So, she agreed, like, y’know, [sighs], ‘OK.’”

Track One: Dog Shaker

The sessions for what would turn out to be the Bangles’ Different Light album were conducted at Sunset Sound Factory in Los Angeles. The facility, much used in the ’60s and ’70s by the likes of the Jackson 5, Brian Wilson and Linda Ronstadt, had become an offshoot of the nearby Sunset Sound complex in 1981. The room that Kahne and the Bangles recorded in was built around a custom API desk.

“I’ve never worked on an API desk that didn’t sound great,” says Kahne. “The EQs and preamps are just wonderful. They had one too in Sunset Sound in the Prince room [Studio Three] that was even more custom and that I worked in with the Bangles a lot. There were other good desks in LA, but I worked at Sound Factory a lot.

“It was 24‑track tape and I think the monitors were JBLs. But also, I used Auratones a lot of the time once I recorded, cause I’m very vocal‑centric. So, Auratones allowed me to know more about what was going on with the voice.”

A typical working day in the studio for the Bangles and producer David Kahne, 1986.Photo: Lester Cohen

A typical working day in the studio for the Bangles and producer David Kahne, 1986.Photo: Lester Cohen

At Sunset Sound Factory, David Kahne initially worked alone on ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’, starting by recording the shaker track that was to give the track its distinctive swing. “We were on tape, of course,” he stresses. “So, I made this tape that had about 10 minutes of click on it.

“This is another one of my strongest memories of the track,” he adds as an aside. “I was going through a horrible divorce, so I was constantly distracted and depressed. My life was completely screwed up. I got a bad lawyer call right before I did it.

“I went out there to put something down and I had this papier mâché dog’s head that was filled with beans. So, I put the thing in record and I ran out in front of the mic with this papier mâché dog’s head shaker — this stupid Mexican‑faced Day Of The Dead‑type thing — and I made the shaker part.

“I have this strong memory of staring at that dog’s head for about 10 minutes while I was shaking it,” he laughs. “I recorded it and then I edited the tape to get four minutes of shaker that was in the pocket.”

Next, the producer added a LinnDrum beat, playing the pads live to tape rather than programming the patterns. A few years earlier, Kahne had been lucky enough to see and hear a prototype of the LinnDrum’s predecessor, the LM‑1, when Roger Linn brought it to The Automatt in San Francisco.

“Roger brought it over to show Herbie Hancock,” he says. “And he still had it in the breadboard, y’know, on the tray where it was just chips and stuff with alligator clips. We were all going, ‘Holy shit.’ There was a hat sample, a kick sample and a snare sample, and the programming was through the touch pad on a touch‑tone phone. He used that as the input device [laughs]. It was so cool.”

Kahne had subsequently bought his own LinnDrum, which was pre‑SMPTE, hence his approach to the drum part on ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’. “I played it in by hand onto the tape, cause I was going to that track that I made with the dog’s head. You could start the tape, you could push play [on the LinnDrum] and it might be in sync. But it was better just to play along. It also makes it a bit looser.”

It’s understandable, perhaps, that being the Bangles’ drummer, Debbi Peterson was opposed to the LinnDrum rhythm track method. “Oh yeah,” Kahne acknowledges. “But she played drums over it. I might have fixed them a little bit when she wasn’t there [laughs].”

Other important additions to the drums on ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ were the metallic sounds and percussive parts supplied by the producer’s recently bought E‑mu Emulator II sampling keyboard. “It cost $14,000 and it had this massive 32MB of RAM,” he quips. “So, the bongo drums and the clanks are from that instrument. And I sold that thing for 500 dollars. But I think because I used it on ‘Egyptian’, maybe, y’know, it was a net gain.”

The propulsive rhythm track in place, Kahne and the Bangles turned to bass and guitars. Michael Steele’s bass was added through a blend of amped and DI’d sounds. “She had a Rickenbacker and she had a Hagstrom,” the producer says. “She might have played the Hagstrom or she might have done a pass on either one as we worked up the bassline. She’s a really good bass player.”

Guitars‑wise, the track involved a main chugging, dampened rhythm part, a second of crashing power chords and a solo from Vicki Peterson. The Bangles were known for highlighting their ’60s influences by using Rickenbackers. “I think I played initially the guitar and then Vicki came in,” says Kahne. “I don’t know if Sue played on that. A lot of times she didn’t play or we’d just get a rhythm part and then replace it. But I think it was mostly Vicki and myself.

“It took a long time to work that solo out, that one at the end. That ‘da‑da‑da‑dit‑dit‑dit’, that little phrase. Finally, we got that and that was sort of the key to build the solo around. We worked on the tone for quite a while.”

Vocals, Breaths & Whistling

When it came to vocals, Kahne used a chain involving a Neumann U47, the API desk preamp and a Universal Audio 1176. At first, the plan was still for the reluctant Debbi Peterson to sing the entire lead vocal.

“We started vocals and Debbi was out singing and we were working on it for a couple of days,” Kahne recollects. “And it was OK, but it sort of deteriorated into this silent argument. Sometimes one of the other girls would come in and go, ‘Hi!’ and wave at her. But they’d be going, ‘When is she gonna get out of there? [laughs].” Cause I always had to be the one that would tell them.

“We started vocals and Debbi was out singing and we were working on it for a couple of days,” Kahne recollects. “And it was OK, but it sort of deteriorated into this silent argument. Sometimes one of the other girls would come in and go, ‘Hi!’ and wave at her. But they’d be going, ‘When is she gonna get out of there? [laughs].” Cause I always had to be the one that would tell them.

“So, finally it fell apart and then I was trying to figure out who else would sing it. They each tried it, and the other three ended up with a verse each. I think it’s Vicki, Micki and then Sue, right?”

Even though Debbi Peterson had previously sung the lead on 1984’s ‘Going Down To Liverpool’ single, when it came to ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’, it seems that her heart just really wasn’t into the song. Hence the baton‑passing verses on the track supplied by the other three members.

“The thing about Debbi, she had a pleasant voice,” Kahne adds. “But on ‘Going Down To Liverpool’ I kept working on the vocal. Working and working. And I had five tracks of it recorded on tape and I didn’t know what to do. I was looking down at the console and I pushed all five faders up. I went, ‘Oh, that sounds good.’ So, I five‑tracked her on ‘Going Down To Liverpool’. That was kind of just the way her sound worked in my opinion. But it didn’t work on ‘Egyptian’.”

Still, Kahne says that the vocals on ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ nevertheless required much in the way of painstaking work. “There was quite a bit of comping. I never got to the point where I had to put it out to run two tape machines. But I would comp and then erase and then do some more vocals and then re‑comp on the console.”

One element that Kahne focused on — which might not seem important — was the use of the singers’ breaths, used to most dramatic effect on Hoffs’ last, stripped‑back chorus.

“I’m really into breaths,” says the producer. “So, where someone takes a breath and how loud it is. There’s a thing at the end when she goes, ‘Walk like an Egyptian’, and then there’s a breath that sounds sort of tired. Well, she didn’t take a breath there. I was on tape and I didn’t have any tracks left and I was afraid I would erase the phrase right before the breath. So, I recorded a bunch of breaths on a two‑track and was trying to fly one in on a second machine. It was nuts.

“It was easier to record the breaths and fly it in than to actually try to get a performance. So, I just found one that I thought, ‘This will work.’ It’s a little bit longer and more tired sounding. And I finally got it in. But while I was doing it, somebody walked in. One of them was in the room, I think it might have been Vicki. She was standing against the wall and another one walked in and I heard her say, ‘What’s he doing?’ And she said, ‘Oh, that thing he always does.’”

When they sang together, they had a tuning in their voices. I mean, that’s their sound. They would sing and it would be very, very accurate.

More live and spontaneous were the Bangles’ backing vocals, typically recorded with all four singing live around one or two mics.

“When they sang together, they had a tuning in their voices,” Kahne points out. “I mean, that’s their sound. They would sing and it would be very, very accurate. It might have sounded like [harmoniser] tuning because it was tripled. But the backgrounds were done as a group, they weren’t individual tracks. I think on ‘Manic Monday’, there was two mics. There might have been two mics on ‘Egyptian’. Sometimes it would be one mic though and that would be fine.”

One last memorable feature of ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ was its earwormy whistling hook. It’s widely believed that it was a part supplied by a keyboard, perhaps the Emulator. Kahne insists not and says that it was him pursing his lips to overdub the melody.

“I whistled on two songs that went number one,” he chuckles. “I whistled on that and on [1999’s] ‘Every Morning’ by Sugar Ray... the whistle solo at the end. So, I’m never gonna try it again cause I don’t want to break my record.”

Set The 1176 To Stun...

Not one to over‑labour his mixes, David Kahne remembers that it was a fairly painless process to get ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ over the finish line. “Yeah, it was easy. It was all organised and I didn’t wait to make decisions at mixing. When I was mixing myself especially, I would always try to just do a few adjustments on some stuff across the stereo bus. But the mixing went fast.”

In terms of reverb options available in the mid ’80s, Kahne says, “The live chambers were around then and the Lexicon [480L] was the go‑to device. I used to hook up a spring reverb sometimes. I think on that song and a couple of other songs on that record, that was the first time I had the idea to sub‑bus. So, I would take a vocal and send it to an 1176 through an aux send, and then put that up on another fader and just push that fader up in the mix a little bit.

“But I’d put the 1176 on stun, y’know, where you push all the buttons in. So, we’d get this super compressed version of the vocal that would come up slightly under the lead vocal and it would add this extra push. One day just for some reason I had that idea and it was a big moment. I guess other people had done that but I didn’t know [laughs]. I showed it to Michael Brauer and he’s used it ever since. He said, ‘What did you just do?’”

It’s a technique that Kahne still employs to this day, even when working in the digital domain. “I have five outboard compressors that are on bus sends out and then I sum analogue through a D‑Box. So, I can send from my computer, the same way that I would send on the aux send on the console, to my sub compressors and EQs, and mix them back to just the degree that I want. It still works well.”

Legacy

Back in 1986, once Kahne had printed his final mix, the producer was pretty sure that ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ would be a big hit. “I had that gut feeling when I was done, even with the turmoil around recording it.”

But when ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ hit the top of the American charts, Debbi Peterson in particular voiced her opposition to both the song and Kahne in an interview with Rolling Stone, saying that she “couldn’t get along” with the producer and dismissing the track as “a nice little novelty song kind of thing... but I don’t feel like it’s us”.

“Debbi was just bagging on me,” Kahne says now. “Y’know, like I’d made them do that and they hated that song. They called it a novelty song. So ‘Manic Monday’ is not a novelty song? I dunno. ‘Going Down To Liverpool’? I dunno. Any time you have a hit, it’s a f**king novelty, right?

“But y’know, I’ve spoken to Sue about it and she was fine with it. It was a fun song for her to sing. She’s very open about stuff. I think just the Petersons, especially Debbie... they were embarrassed. I knew there was a problem and you might have noticed I didn’t produce the next album [laughs]. So, they were free of me.”

The Bangles went on to make their next album, 1988’s Everything (which included their second number‑one hit, ‘Eternal Flame’) with producer Davitt Sigerson (Kiss, Carly Simon). Meanwhile. David Kahne maintained his parallel career as a record company man (becoming head of A&R at Columbia and then Warner Bros) and producer, going on to helm albums for such diverse artists as Paul McCartney, Tony Bennett, the Strokes and Lana Del Rey.

He puts his versatility in the studio down to “probably my curiosity. I’ve always been fascinated why one kind of music was different than another. So, the way that Tony phrased behind [the beat]. Where Paul is just a music machine. His instinct for voice‑leading is impeccable. His ear is just flawless.

“Lana had only been in bands and she’d never gone to beats before, and that’s what I brought to it when we did that record. But I was working with Tony in one studio and Fishbone in another at the same studio one day and I realised, ‘What the f**k am I doing? [laughs]. But there’s a common thread between them all, which is resonance.”

In later years, ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ took on a life of its own, though briefly found itself scratched from radio station playlists in 1990‑91 during the Gulf War, when both Clear Channel in the States and the BBC in the UK deemed its lyric potentially insensitive. David Kahne was however later shown footage from the Egyptian revolution of 2011 where the song’s title had been written on a sign by a protester, turning it into a slogan. “Weird stuff has happened with that song,” he says.

The Bangles broke up in 1989, reformed in 1998 and have clearly all found their peace with ‘Walk Like An Egyptian’ after all these years. They still play the song in their live sets, most recently in 2019. As to the enduring appeal of the track, David Kahne points to its simple catchiness and Linn‑heavy groove. “Part of it is just it’s fun and it’s easy,” he says. “Like, kids sing along to it immediately, which is always important for a single.

“Also, it’s built the way a hip‑hop track is made. I’ve had people ask me if I used ‘beats’. I go, ‘There weren’t ‘beats” then [laughs].’ But y’know, there was a rigidity and power to those grooves and I think that dog head informed the thing, cause shakers tend to have a little swing to ‘em.

“So, it does feel a little more like a beats song and I wonder if that has anything to do with making it sound contemporary. Cause people have told me that it sounds like a contemporary track. It is super catchy and you could take a beat out of that and use it in a track,” he concludes, teasing future samplers and beat‑makers. “Y’know, you could rob a beat.”