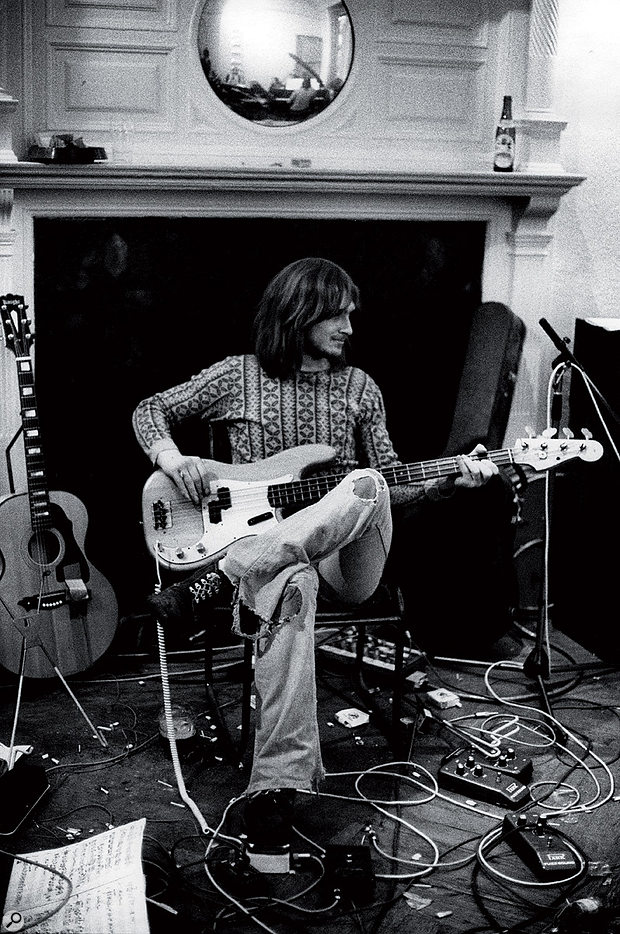

“At least in the old days you could be a bit scruffy” — Mike Oldfield recording some bass.Photo: RedfernsPhoto: Redferns

“At least in the old days you could be a bit scruffy” — Mike Oldfield recording some bass.Photo: RedfernsPhoto: Redferns

Forty years after its original release, Mike Oldfield tells us the story of recording his hugely successful debut album, Tubular Bells.

Featuring an eclectic array of instruments and an equally heterogeneous assortment of sounds and rhythms that, ingeniously blended together, created a sublime, mesmerising, sometimes startling, symphonic trip through New Age prog rock, Tubular Bells was the landmark album that launched Virgin Records — and the career of self-taught 19-year-old English multi-instrumentalist Mike Oldfield.

Tubular Bells was issued in the UK on 25th May 1973, just 10 days after Oldfield's 20th birthday. Comprising two distinct, yet cohesive parts that each occupied an entire side of a long-playing record, it gained worldwide attention after its hypnotic opening piano theme became synonymous with the classic demonic-possession horror film The Exorcist, released at the end of that same year.

Only then did it become a British number one, amid a 279-week run on the chart. Two very different singles were made available to record buyers on either side of the Atlantic: a slapdash edit of the first eight minutes of Part One, assembled by American distributor Atlantic Records without Oldfield's authorisation, which reached number seven on the Billboard Hot 100 in May 1974; and his own re-recording of Part Two's 'bagpipe guitars', centred around Lindsay Cooper's oboe and released the following month as 'Mike Oldfield's Single'. This peaked at 31 in the UK.

That September, The Orchestral Tubular Bells, arranged by David Bedford, was performed by the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra at London's Royal Albert Hall. Oldfield subsequently added his own contribution to the album, in the form of an acoustic guitar overdubbed at Worcester Cathedral, and since then, alongside a plethora of other projects, he has released several sequels to the original record: Tubular Bells II (1992), Tubular Bells III (1998), The Millennium Bell (1999) and Tubular Bells 2003, which was a digital re-recording of the original.

The 1973 record, issued on the same day as Virgin's second and third releases, boasted the catalogue number V2001. However, after Mike Oldfield's deal with the label ended in 2008, he retrieved the rights to Tubular Bells and transferred them to Mercury Records, which issued a remixed and remastered version the following year. Now, 40 years after the original, comes the club remix album Tubular Beats, released on Edel in Germany, and featuring Oldfield's collaboration with Torsten Stenzel of fraternal German electronica duo York, which melds old and new to transport the music into the realm of trance.

"Torsten runs these Ministry of Sound club events in Antigua, and a couple of years ago, after I was put in touch with him by my publishers at BMG, he got on a plane and flew to Nassau,” Mike Oldfield says from his home in the Bahamas. "For a day, we sat down in my studio and talked about collaborating on a club album, rather than the remixer just going off and doing his own thing. So that's what we ended up doing, sending files back and forth over the Internet. We'd each tweak them and make suggestions, but we also used samples from the original album that had already been transferred from Ampex tape to digital and remixed by me here in 5.1

"I'd send those samples to Torsten and look forward to receiving the new version, making comments, doing some tweaking and sending it back. That said, you're so, so limited in terms of what you can do with club beats. Everything is centred around the bass line or some synthesizer pattern that's going on underneath it, so we couldn't make many key changes and we couldn't have more than two chords. We could have the beginning of Tubular Bells and the end, but we couldn't have the whole pattern; only a bit of it. The record is totally geared towards the clubs and, since he did about 75 percent of the work, it's more Torsten's album than mine.”

Early Years

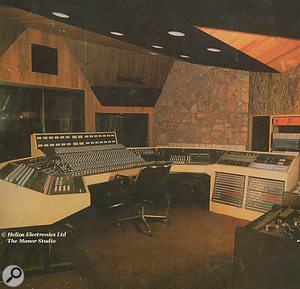

The Manor at Shipton-on-Cherwell, where Tubular Bells was recorded. Sold after Virgin was bought out by EMI in the mid-'90s, the house is now back in private ownership.

The Manor at Shipton-on-Cherwell, where Tubular Bells was recorded. Sold after Virgin was bought out by EMI in the mid-'90s, the house is now back in private ownership.

Born and raised in Reading, Berkshire, Mike Oldfield began teaching himself to play the guitar at the age of 10. "I got my technique from listening to Bert Jansch and John Renbourn guitar instrumentals on a Dansette [portable mono record player], lifting up and plonking down the needle hundreds of times to copy what I heard,” he explains. "I was playing in folk clubs by the age of 11 or 12, both on my own and with various other friends, earning about £4 a gig.”

At the age of 13 Oldfield relocated with his family to Harold Wood, and in 1967 he formed a folk duo named Sallyangie, with his sister Sally.

"She was best friends at school with Marianne Faithfull,” he continues, "and we used to visit her and Mick Jagger at their house in Cheyne Walk [Chelsea]. One day, Mick took us to the nearby Sound Techniques studio, where he produced — and Gus Dudgeon engineered — a couple of tracks featuring Sally, me and an Indian tabla player named Rafiq. I don't know whatever became of those recordings. They just got lost in the mists of time. But that was my very first studio experience.”

After the release of Sallyangie's 1969 album Children Of The Sun, Mike Oldfield joined singer Kevin Ayers' group the Whole World as a bass guitarist, while playing a number of different instruments on a couple of their albums.

"We recorded at Abbey Road at around the time the Beatles were still working there and Studio 2 was chock-a-block full of instruments,” Oldfield recalls. "It was an Aladdin's Cave with a tremendous vibe. Everything was there, from orchestral percussion to beautiful pianos, harpsichords, a Mellotron and even a set of tubular bells. If a session started at noon, I'd go in there at eight o'clock in the morning and spend four hours experimenting with all those instruments. That's how I learned to play so many different things.

"I've always had a natural aptitude for picking up an instrument or hearing an unfamiliar tune and being able to play it almost straight away. I can play anything that's stringed with frets, as well as anything I can hit. I can't, however, play any wind instruments — like flute or saxophone — and I'm not very good with fretless strings like the violin or cello. I once forced myself to read a book about musical notation, and I'm still very, very slow at it. If I have to, I can write things down. But I don't like to, and these days it's unnecessary, as software does it for me.”

In 1971, during a few days' break from touring with the Whole World, Oldfield supplemented his bass and acoustic guitars with a Farfisa organ that he borrowed from Kevin Ayers, along with a Bang & Olufsen Beocord quarter-inch two-track machine that he could use to record himself at home in his small flat in Tottenham, North London.

An old Helios brochure showing the desk that Richard Branson bought for the Manor's control room with some of the profits from Tubular Bells."I was listening to a lot of classical music at that time, especially Bach, along with 'A Rainbow In Curved Air' by Terry Riley,” Oldfield says, referring to a piece of music that saw the keyboardist and classical minimalist experiment with overdubbing techniques to play all of the instruments, including an organ, electronic harpsichord, tambourine and goblet drum. "I loved the repetitive two-part pattern that he played on both keyboards, one starting halfway through the other. Well, having tinkered around on our family's piano throughout my childhood — while my sister could read music and play it properly — I now taught myself to play that repetitive pattern with both hands.

An old Helios brochure showing the desk that Richard Branson bought for the Manor's control room with some of the profits from Tubular Bells."I was listening to a lot of classical music at that time, especially Bach, along with 'A Rainbow In Curved Air' by Terry Riley,” Oldfield says, referring to a piece of music that saw the keyboardist and classical minimalist experiment with overdubbing techniques to play all of the instruments, including an organ, electronic harpsichord, tambourine and goblet drum. "I loved the repetitive two-part pattern that he played on both keyboards, one starting halfway through the other. Well, having tinkered around on our family's piano throughout my childhood — while my sister could read music and play it properly — I now taught myself to play that repetitive pattern with both hands.

"Doctoring the Bang & Olufsen machine with wire snippers and sticky tape to block off the erase head, I was able to bounce from one track to the other, adding a bass line to create sound on sound, while also tinkling on little children's bells that we used onstage in Kevin Ayers' band. This would later evolve into the repetitive piano and glockenspiel Exorcist piece that you often hear on Halloween.

"I wanted to create a long piece of instrumental music, because at that time there was a fantastic jazz orchestra called Centipede,” Oldfield explains. "Its leader was Keith Tippett, it contained the coolest, hippest musicians, and they'd play a long instrumental piece that, although it never translated well to disc [on 1971's Robert Fripp-produced Septober Energydouble album], was absolutely superb when performed live. That was the biggest single inspiration: I wanted to make a piece of music like that, although maybe a bit more rocky and less jazzy.

"While 'Caveman' didn't have any voice on it, 'Peace' was a lovely, quiet tune with beautiful chords that had been kicking around in my head for a couple of years, and the only instrument I could play it on was the Farfisa. I recorded those demos over the course of two or three months until Kevin Ayers decided he was going to write a new album and took his tape recorder back. That was the end of my demo writing, and so I then began taking my tapes around to all of the London record companies.

"By then, I had a little bit of a name through papers like Melody Maker. Whenever Kevin played and somebody bothered to review it, I would be mentioned. However, I was turned down by Harvest — which was Pink Floyd's label — as well as by CBS, Island, Pye and various other companies, and in the end I just gave up. The main problem was that my music had no drums and no vocals. These days, it's 10 times worse, since you need to have a good looking person with snow-white teeth who can dance. At least in the old days you could be a bit scruffy, but I was despondent because something inside me knew my music was right and that, if I got the opportunity to record it properly, people would love it. I just had a gut feeling about it.

"For a little while, having completely given up, I joined the Sensational Alex Harvey Band, playing guitar. Alex was the rhythm guitarist in the musical Hair at the Shaftesbury Theatre, and I used to deputise for him when he couldn't do it. I'd play guitar on 'Let The Sunshine In', and after about 10 shows, getting a bit bored, I kind of jazzed it up and put it into 7/8 time. Well, you should have seen the looks I got from the brass players and, as the singers now couldn't dance, I was fired from my only foray into the theatrical world.”

The Manor

Next, working with singer/songwriter and guitarist Arthur Louis who specialised in rock, blues and reggae crossover, Mike Oldfield rehearsed at a studio named The Manor, located within a manor house in the village of Shipton-on-Cherwell, just north of Oxford. Still under construction, the UK's first residential facility was owned by one Richard Branson, the co-founder of Virgin Records.

"Since the studio was being built in what used to be the squash court, we were rehearsing in one of the other rooms,” Oldfield recalls. "Chatting to the engineers, I said, 'I've got these demos. Would you like to have a listen?' Looking for new artists, they said, 'Sure,' and the roadie then drove me all the way back to London so I could retrieve the tape. Had he not offered to drive me, I'm pretty sure I would have never made Tubular Bells, which is incredible.

"Anyway, I played the demos to the two engineers, Tom Newman and Simon Heyworth, and they liked them. So they gave them to Simon Draper, who was the creative side of Richard Branson, and I didn't hear anything for a whole year. During that time, I was pretty much a starving musician, getting handouts from my girlfriend and my mother, and after reading about becoming a state-employed musician in Moscow, I decided to contact the Soviet Embassy. I wasn't a communist; I just needed to eat. However, just as I was looking through the phone directory for the Embassy's number, I got a call from Simon Draper saying, 'We'd like you to come and have dinner with us on Richard's boat in a few days.'

"When I met with them, Richard said, 'We're going to give you a week in our new studio to see what you can do.' I said, 'OK, but I'm going to need some instruments. Can you rent them for me?' 'Yes,' said Richard, handing me a pen and paper, and so, informed that the studio already had Hammond and Lowrey organs as well as two nice pianos, I wrote down what I needed: all the different types of guitars, a vibraphone, a set of orchestral timpani, various kinds of percussion, a glockenspiel, flageolet, a Farfisa and a mandolin that I'd use for the 'Part Two' finale, 'The Sailor's Hornpipe'. Elsewhere on the record, I'd create the sound of a mandolin by playing an electric guitar at half speed and then speeding it up again.

"Tubular bells weren't on the list,” he continues. "However, when I turned up at the studio a couple of weeks later, all of my gear was being unloaded out of a rental company truck at the same time as John Cale was leaving. Spotting a set of tubular bells being wheeled out the door, I said, 'I might be able to use those. Can I have them as well?' The response was positive, so they were wheeled back in, and if it wasn't for that, the record would have turned out quite differently, with a different name. It's amazing how the parts of the puzzle fit together.

"Since I'd recorded the demos, I had been living at my mother's house and my grandmother's old upright piano was there. My grandma used to play in the pubs — 'Roll Out the Barrel', those kinds of songs — and while spending the better part of a year playing that old honky tonk, I'd started writing things down in my own special way: bits of music, a little plan here, a diagram there, and arrows pointing here and there. All of 'Part One' was mapped out in my special musical language — both in a notebook and in my mind — and so I knew exactly what to do once I got into the studio.”

A Sticky Start

"Getting going was actually the most challenging aspect of that entire project. I started off by just playing the piano and then tried to overdub on top of it, but it really wasn't working in terms of the timing. Very quickly, I was getting worried, but then someone came up with the idea of recording a clockwork metronome, and once I effectively had that as a click track it was much easier to get everything sounding together.

"A lot of Tubular Bells was in odd time signatures, with beats dropped all over the place and cycles of music with five different tunes in different times, moulded together but only coming together at one point, 162 beats down the road. Then the cycle would start again at the beginning of 'Part Two', and it took a lot to work that out on paper and inside my head. Then again, from a physical standpoint another challenge was the up-tempo bass line at the end of 'Part One'. I played the whole thing for about five minutes and by the time I'd finished my fingers were almost bleeding.”

Less problematic and altogether more gratifying was Mike Oldfield's use of the iconic tubular bell.

"That appeared in a quiet section in the middle of 'Part One',” he says, "and then, when I got around to doing the end of 'Part One' over that fast bass riff, I wanted to introduce the instruments one by one in the order that they appeared — the cast in order of appearance. My week-long session was coming to an end and the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band were due to start recording at the studio the next day. So, as the group members were already there, I asked Viv Stanshall — who was a bit worse for wear due to alcohol, but still just about able to stand up — if he would serve as the Master of Ceremonies and introduce the instruments.”

Stanshall agreed, and his grand, climactic announcement of the tubular bells is what resulted in them lending their name to an album which had the working title of Opus One and which Richard Branson suggested should be called Breakfast In Bed. Moreover, a drunken Stanshall also recorded a 4am tour of The Manor. Cut from the final release, this was reinserted as an extension of the 'Sailor's Hornpipe' finale at the end of 'Part Two' on the 1976 Boxed compilation that featured quadrophonic remixes of Mike Oldfield's first three albums.

In the case of the original Tubular Bells, the title instrument appeared at the end of 'Part One'.

"As the hammer that came with it would only produce a little ding, I asked for a bigger hammer and someone brought me one for hammering nails,” Oldfield recalls. "'That's no good,' I told him. 'Get me a big hammer!' So I ended up with this really huge hammer, Tom Newman miked the tubular bell with a beautiful Neumann valve mic, and I took a run at it and gave it a huge wallop. Like everything else on the album, it was done in one take — the only exception being two takes of the 'caveman' (see 'Vocals, Grunting & Other Noises' box) — which is why there are so many mistakes on the record in terms of wrong notes, bits that are out of tune and so on.

"Although it was distorted, that distortion was part of the whole effect. However, a couple of years later, some engineer who will remain nameless persuaded me to erase that hammer hit and replace it with a clean one which didn't work at all. To this day, the original tubular bell has been lost, due to that purist approach of avoiding all distortion, and I could really throttle that guy for insisting he knew best. The only place you can hear the original bell is on the two-track master; it's not on the multitrack anymore. As a result, what you hear on the 2009 remixed album is the quiet version that appeared about halfway through 'Part One', roughed up by me and blended with a sample of the two-track master, just to get a quarter of a second of that distortion on the edge of the bell. However, although it is harmonically correct, it's still not as good as the original.”

'Part Two'

Mike Oldfield conceived Tubular Bells from the beginning as two long pieces suited to the two sides of a vinyl disc, and recorded all of 'Part One' during the week at The Manor that served as his audition in November 1972. Then, once Simon Draper assured him he had made the grade, Oldfield was allowed to stay on and use the down time — often on days off or in the middle of the night, when nobody else was using the studio — to record 'Part Two' from November through to the following April.

The earnings from Tubular Bells would soon enable Richard Branson to equip The Manor with a Helios desk. Before that happened, however, the album was recorded using a 20-channel console designed and built by Birmingham-based Audio Developments, and a 16-track Ampex two-inch tape machine with Dolby.

"As the electric guitar parts were all DI'd, I played them sitting on the floor in front of the mixer, whereas anything acoustic was performed in the main studio where all of the keyboards resided,” Oldfield says. "The sound was good, except for the mains hum that runs throughout Tubular Bells. They didn't quite get the earthing sorted out. So, when they got around to remixing the album in 5.1, they'd have to filter out the hum on every track.

"Since 'Part One' came together like magic, I didn't need to vary from the map in my head and on paper. That said, there were places where I wanted to have an organ chord that made a rising, whirring sound. So I asked the engineers how we could do that and they told me they had this voltage-controlled motor-drive transformer. This meant that we could play the chord and make a loop with sticky tape on the two-track. Then we could plug the machine into the voltage of the motor and, by varying the voltage going to the motor, we could speed up and slow down the tape machine. So we'd cue it all up and, at the right point when the multitrack went into record, I'd have this great big knob set up with a Chinagraph mark indicating where I wanted it to start and where I wanted it to end. By manually moving the big Bakelite knob, I'd then change the voltage on the two-track to get the whirring organ sound that I wanted.”

In 'Part Two', the distorted, double-speed 'bagpipe guitars' were created by using a Glorifindel fuzz box and recording at half speed.

"There were a couple of those parts,” says Oldfield, "and then another one played either a fourth below or a fifth above to get the bagpipe harmonics. I didn't set out trying to make the guitars sound like bagpipes, but they did, and so that's how they were described on the album cover as part of the marketing.

"I had various bits mapped out for the record's second side, but other parts were improvised. For example, near the end, before 'The Sailor's Hornpipe', there's a long bass line with some chords, and I was always going to improvise over that. On the other hand, while I had the 'caveman' backing, I didn't know there was actually going to be a caveman. Steve Broughton — the drummer for the Edgar Broughton Band — and I laid down drums and bass, and the backing track sounded fantastic even with just two instruments. But then I didn't know what the hell to put on top of it. I tried a bit of organ, a bit of piano, but nothing worked.

The Final Hurdle

"We'd do all of these improvised things, but mixing that record took a month and was a total nightmare. We had five people swarming all over the mixer, operating every channel according to little Chinagraph marks. Everyone would have to go to position number one; then, five seconds in, position number two. You see, about 1800 separate overdubs on both sides had to fit on 16 tracks of tape, and then they had to be mixed. Neither engineer knew what he was in for when I started, and by the time it was finished we had filled up nearly every space on every track.

"One track might have 30 seconds of guitar followed by a bass, a keyboard and a bit of percussion, and every track was like that. During the mix, every one of those sections had to be panned, EQ'd, given echo and adjusted to the right level. If we'd had the resources, I suppose we could have acquired another sub-mixer and another tape machine, but the money wasn't available and so we were stuck with what we had.”

There was no cause for concern. Tubular Bells would sell more than two-and-a-half million copies in the UK and in excess of 15 million worldwide, while eventually displacing Oldfield's second album, Hergest Ridge, atop the British album chart. Going gold in the USA, it earned the artist a 1975 Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Composition, since when it has has re-entered the UK chart during each ensuing decade.

Vocals, Grunting & Other Noises

"Richard Branson and Simon Draper took the unfinished album to MIDEM in the South of France and played it to various people, who said there needed to be some vocals and drums,” explains Mike Oldfield. "When Richard told me this, I went down into The Manor's wine cellar, found a bottle of Jameson's Irish Whiskey and drank most of it. At that point, a microphone was put in front of me and I made those caveman noises.”

Indeed, the 'Piltdown Man', as the character came to be known, was achieved by Oldfield grunting, growling and shouting into a mic while being recorded at a higher speed using a voltage control unit so that, when played back at a normal speed, his voice sounded deep and gruff.

"Back then, I was absolutely useless as a vocalist and as a lyricist, and I actually damaged my larynx doing that part,” he admits. "Afterwards, I couldn't speak a word for about two weeks. Still, that also ended up being the only bit of Tubular Bells that had drums, vaguely conforming to the norm.”

Other vocal parts were contributed by Sally Oldfield, Mundy Ellis and a 'Manor Choir' comprising the engineers, the featured artist and, according to him, "the people who worked in the kitchen, the gardeners, everybody. We got the whole household humming along to the little honky-tonk piano part; a reference to my grandmother playing in the pub.”