"Do you have the time to listen to me whine?” asked Green Day in the opening lines of their song 'Basket Case'. For 16 million people, the answer was apparently 'yes'...

Green Day's Billie Joe Armstrong on stage, 1994.Photo: Kelly A Swift/Retna

Green Day's Billie Joe Armstrong on stage, 1994.Photo: Kelly A Swift/Retna

Punk rockers, punk revivalists, neo‑punks, pop‑punks, post‑Nirvana alternative rockers... Many labels have been attached to them, various musical predecessors have paved the way for their success, and many accusations of selling out have been hurled their way by hard‑core punk fans after the band quit the independent Lookout! Records label and signed with Reprise. Regardless of all this, Green Day's Northern California triumvirate of singer/guitarist Billie Joe Armstrong, bassist/backing vocalist Mike Dirnt and drummer Tré Cool have done more than most during the past couple of decades to bring punk to the mainstream, and introduce it to new generations.

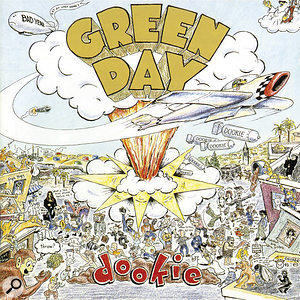

Following the underground success of the band's second album, Kerplunk, which sold about 50,000 copies in the US following its January 1992 release — and which has since become one of the best‑selling indie albums of all time, with over 750,000 sales in America and more than a million worldwide — Green Day's major label debut, Dookie, achieved global recognition. At a time when Nirvana were still at the vanguard of the alternative rock movement, it distinguished itself with a characteristically punkish energy and snottily adolescent, don't‑give‑a‑shit attitude that was reflected in the album's title. (A 'liquid dookie' was the band members' term for the diarrhoea they'd suffer when eating lousy food on the road. However, when this was considered perhaps a little off‑putting to potential record buyers, only the second half of the phrase was retained.)

Issued in February 1994, Dookie would spawn five hit singles — 'Longview', 'Welcome To Paradise' (a re‑recording of a track on Kerplunk), 'Basket Case', 'When I Come Around' and 'She' — and, with worldwide sales of over 16 million units, would prove to be the group's most popular work, while establishing them at the forefront of the neo‑punk scene. Not a bad return on an investment of just over three weeks of recording sessions at Fantasy Studios in Berkeley, California, during September and October of 1993, and quite a coup for Rob Cavallo, who signed the band to Reprise and would subsequently co‑produce all of their albums through to 2004's punk-opera opus, American Idiot.

Ready To Go

Neill King in the studio, mid‑1990s.

Neill King in the studio, mid‑1990s.

Although pursued by other major labels, Green Day were impressed by Cavallo's production of the eponymous debut record by Southern Californian rockers the Muffs, so they handed the junior A&R man the demos of the songs they had already written for their next album. There would be 15 in total on Dookie, all of them composed by the band, with lyrics by Billie Joe Armstrong, except for 'Emenius Sleep', which was penned by Mike Dirnt, and the hidden track 'All By Myself', which was written by Tré Cool. As Cavallo would later recall in an interview with VH1, when he played the tape in his car, he immediately knew he "had stumbled on something big.”

Travelling to Berkeley to meet the band members, he got stoned with them during a 40‑minute jam session and then, having impressed the trio with his genuine appreciation of their music — and been impressed by their own ability to play that music — persuaded them to sign with Reprise.

"Everything was already written, all we had to do was play it,” Billie Joe Armstrong would later recall about the Dookie sessions, while Neill King, who engineered the record, confirms this: "The guys had been performing many of the songs live, so they were very familiar with them when they entered the studio and they had supreme confidence in them. They knew they were hot shit, they knew the material was terrific, and it was just a case of us getting it right.”

Born in Wimbledon, South London, in 1957, King originally studied classical music and played the trumpet at the Guildhall School Of Music, but harboured a desire to sit behind a control‑room console.

"I'd always wanted to get into studios since I was 15 or 16, when I figured out what those credits meant on the back of albums,” he recalls. "I was fascinated with musical arrangements and recording and how you could get sounds from different rooms. I knew I wanted to be a record producer, but this was the late '70s when there were no college courses and no clear path that led to that position.”

Accordingly, King decided to become an engineer, and secured a trainee post at Eden Studios in Chiswick, where many of the clients were on the Stiff Records roster. In August 1978, the tape‑op‑cum‑tea-boy acquired his first control-room experience during sessions for Elvis Costello's Armed Forces album. The engineer on that record was Roger Bechirian, and he served as Neill King's mentor on several projects before King himself gained full engineering credits with, among others, Squeeze, Shakin' Stevens, Phil Everly, John Hiatt, Cliff Richard and the Smiths.

After going freelance, King recorded A‑Ha, Dr Feelgood, Little Richard, Elvis Costello, Carlene Carter and Transvision Vamp, and in 1990, when he felt that the London music scene was becoming a little too dance‑oriented for his own liking, he relocated first to Los Angeles and then further north to the Bay Area, to be closer to his wife's family. While familiarising himself with local studios such as the Record Plant and Fantasy, King worked on projects with Robert Cray, Celine Dion, En Vogue and Joe Satriani, before Green Day entered his life.

The Who Directive

The drum mic setup in Fantasy's Studio A as it was for the recording of Dookie. This includes a pair of Telefunken tube 251s as overheads, an AKG D112 and a 421 for the kick, an SM57 on top of the snare and an AKG 451 underneath, Sennheiser MD421s for the toms (AKG 414s were also used) and Neumann M49s for the room.Photo: Fantasy Studios

The drum mic setup in Fantasy's Studio A as it was for the recording of Dookie. This includes a pair of Telefunken tube 251s as overheads, an AKG D112 and a 421 for the kick, an SM57 on top of the snare and an AKG 451 underneath, Sennheiser MD421s for the toms (AKG 414s were also used) and Neumann M49s for the room.Photo: Fantasy Studios

"I was working out of Fantasy in Berkeley as my studio of choice,” he recalls about the legendary facility that, since its launch in 1968, has been used by artists ranging from Creedence Clearwater Revival, Aerosmith, Journey, Santana and Counting Crows to Tony Bennett, Herbie Hancock, Woody Herman and Cannonball Adderley. "The guys had been living in Berkeley on bread and water. Now, with a major record deal, there was a lot more money available, but they decided they still wanted to stay local. And since they'd be producing the record with Rob Cavallo and Rob didn't have much experience in that line of work, they were looking for an engineer who could get a good sound. The band members knew what they were doing, and having an A&R man as their producer certainly had its advantages. Rob signed the cheques and bought the meals. Having been so poor and starving, the guys appreciated going to these great restaurants around Berkeley and San Francisco. On a couple of occasions I went back to Billie Joe's place, which was basically a squat, and it was amazing to see how, within a very short space of time, their lives would change. They were very ambitious, especially Billie Joe, who had a vision and wanted to bring their music to a much wider audience.”

King states that, in terms of the desired sound, he was told to refer to the Who album Who's Next.

"I'm not sure why,” he says, "except that Tré as a drummer is very close in terms of his attitude to Keith Moon... He had that kind of wild animal approach to playing drums. He wasn't uptight, he wasn't too worried about getting everything just so. It was all attitude, and very exciting. So I think that's where the Who directive came from, and I know they liked the Undertones as well. I can't hear anything that we did that sounds remotely like anything off Who's Next or any Who song, but it was probably just a case of trying to get the outrageous vibe of the drums.”

Backing Tracks

Outboard gear in Fantasy's Studio A control room. On the left‑hand side is a rack of five Neve 8078 mic pres above two racks of six Neve 8078 mic pres. To the right of these is a rack of Telefunken 672 eight mic pres and, further to the right, a pair of Teletronix LA2A Tube Limiters, beneath which is a DBX 160 Compressor/Limiter. At the far right are a pair of Urei LN 'black face' 1176s and a pair of 'blue stripe' 1176s with an LN upgrade. Photo: Fantasy Studios

Outboard gear in Fantasy's Studio A control room. On the left‑hand side is a rack of five Neve 8078 mic pres above two racks of six Neve 8078 mic pres. To the right of these is a rack of Telefunken 672 eight mic pres and, further to the right, a pair of Teletronix LA2A Tube Limiters, beneath which is a DBX 160 Compressor/Limiter. At the far right are a pair of Urei LN 'black face' 1176s and a pair of 'blue stripe' 1176s with an LN upgrade. Photo: Fantasy Studios

The basic tracks for Dookie were recorded in one of Fantasy's two tracking rooms, Studio A, which housed an older 56‑channel Neve 8108 console. As seen through the control room window, Tré Cool's drums were in the centre of the live area, screened off with some half‑gobos to contain the sound a little, while Mike Dirnt played his bass to the left of the kit, with his amp housed in an adjacent booth. Billie Joe Armstrong played his guitar on the other side of the kit, his amp placed in a booth located just past the machine room, to the right of the control room, while he himself was screened off to avoid spillage into his vocal mic while he performed guide vocals.

"I brought in some extra Neve preamps and there were a couple of Studer A800 machines on which we played two‑inch tape at 15ips,” King says. "We did about 10 days of tracking in there, as well as some overdubs — we didn't work weekends, just Monday to Friday, noon to midnight with a little dinner break — and I also did a lot of multitrack editing, which back then was viewed as some sort of archaic, magical thing. Very few people were still cutting tape, especially two‑inch, but I'd slice up drum tracks and cobble them all together.

"It's not that Tré wasn't a good drummer, but in terms of his performances we wanted the best of the best. In line with the Who directive, we wanted to let him sound exciting, but back in the early‑'90s you couldn't get a record played on the radio if it wasn't in time, even a rock & roll record. So, although we wanted him to do all of his wild fills and crazy drumming, we couldn't just let him go. He'd drift in and out of time, which is terrific live, but which was unacceptable on radio at that time. We were still under the tyranny of the click track. We'd therefore let him play, but we would take a fantastic tom fill that he did and insert that into one of his better bed tracks.

"Often, we might do three or four takes of a particular song, and then I would use one of them for the first verse, a different take for the middle eight and maybe switch to another one for the outro. It could be quite a combination of different drum performances. We may have punched in on the drum track a couple of times. Back then, you couldn't really punch out so easily on drum takes unless there was a big gap. You could hear it — there would be a little blip. So splicing was the way to go... as long as you had somebody who could edit tape.”

The Details

The mic setup for recording Billie Joe Armstrong's guitar overdubs in Fantasy's Studio B. The Marshall cab's two best cones are miked with an SM57 and a Sennheiser MD421. To the left you can see a U87 being used as a room mic. Photo: Fantasy Studios

The mic setup for recording Billie Joe Armstrong's guitar overdubs in Fantasy's Studio B. The Marshall cab's two best cones are miked with an SM57 and a Sennheiser MD421. To the left you can see a U87 being used as a room mic. Photo: Fantasy Studios

"Right from getting the drum sound, everything seemed to click,” Rob Cavallo would later recollect. "We always knew it. Every time we had a take that was the right take, it was like Tré would throw his sticks and you would always hear them click, hitting the floor — and then we would take a break.”

Not that Neill King claims to have done anything out of the ordinary in order to acquire said sound.

"We had some beautiful Telefunken tube 251s, which I used as overheads,” he explains, "while the kick drum was typically recorded with a [AKG] D112, and a [Sennheiser MD] 421 just to give it a little more presence. There was a 57 on top of the snare and a little bit of AKG 451 on the bottom as well as on the hi‑hat, which had a ‑20 dB pad. For the toms, I usually used AKG 414s, and we had some old Neumann M49s for the room. We basically used the whole room for the drum sound.

"The bass was DI'd and it also went through an Ampeg rig, for which I would use two mics: the Neumann FET 47 and a little 84 spot mic — about four inches long, three‑quarter‑inch diameter — that seemed to work quite well on the bass cabinet. It was after the drums had been recorded that we stayed in the room to redo all the bass tracks, which were done very quickly, but which sounded so much better when they weren't limited to just one run‑through. Again, it wasn't that Mike was a bad player; it was simply a means of getting everything just as we liked it. I'd have to go back to early‑'80s rock sessions with Elvis Costello or Nick Lowe or Shakin' Stevens to remember when we last retained the original bass and just punched in parts for those places where it might have been a little off. At this point, everything was redone. Every mic that was in the room was just for the drums, and the bass and guitar weren't loud enough to get on any of the drum mics... I probably used about 12 or 14 tracks for all the drums, because we could — with a 24‑track tape machine, I could put up some spurious little mics, and then decide whether to use them or not.”

Overdubs

The Neumann U87 and Beyer M201 used for recording the vocal overdubs in Studio B. Photo: Fantasy Studio

The Neumann U87 and Beyer M201 used for recording the vocal overdubs in Studio B. Photo: Fantasy Studio

"We recorded drums, bass, guide vocals and guide guitars in Studio A, and after we got a great bass sound and rented a couple of bass guitars, Mike redid his parts on a black, fairly new [Fender] Precision. Then, once I'd bounced everything down to a second 24‑track tape, we moved to the overdub room, Fantasy Studio B, and spent two five‑day weeks doing the vocals, backing vocals and guitars. It housed a Trident 80B console and that studio space was pretty small, but it didn't really matter. We were just monitoring, and then I had the vocals going through some nice preamps and compressors and pretty much going straight to tape.

"Billie Joe tried out a couple of different amps and a bunch of different guitars, his cheap Mexican Fernandez Strat being one of the main things he used for playing rhythm. He played in the control room unless there was some feedback we needed, and we'd have the heads there, run lines out to the Marshall cabinet in the studio, and have two close mics, a [Shure] SM57 and [Sennheiser] 421, on the two best‑sounding cones, as well as a [Neumann] U87 about five yards back, for a little room. There was usually just a left and right track, as well as maybe a third one that we boosted somewhere, and then a couple of single‑line solos here and there. As he'd already been playing these songs for a while, he was so quick and nothing was laboured.

"We detuned everything down to E-flat, and while it was a great idea that gave the guitar sound a really nice low end — an old heavy-metal trick — it became difficult in terms of intonation. You know, it was OK putting down one guitar, but we ran into some problems trying to double it. Once you start layering guitars, everything has to be so in tune or it'll stick out. It's great plugging your Les Paul into a Marshall and playing a blistering track, but then if you have to double‑track it precisely and all of the harmonic distortion is doubled, it can sound distinctly out of tune. So while it could sound great, we had to work a lot on tuning and intonation. Still, it wasn't too much of a pain, because Billie Joe is just a star, and he could rattle off his tracks and solos.”

Ditto Armstrong's vocals, which were recorded with a Beyer 201.

"Even when he shouts, there's a very distinct tone to his voice, and having used that mic before on quite a few singers, I knew it would be perfect for capturing that tone,” King says. "The 201 combines the best of a large diaphragm and the best of a dynamic, and it was perfect for his voice. He was very quick. He'd do three or four takes, because we were working on the slave machine at that point, and after the guys left I'd usually be on my own to comp from those vocal tracks. They were all great, I'd just comp the best of the best, and then the guys would come back in and either say, 'That sounds great,' or 'There's a better line for this,' in which case I'd punch in a couple of things they might like, and that was it.”

Bone Dry Mixing

The SSL E/G‑series and sync'ed Studer A800 MkIIIs used for the first mix in Fantasy's Studio D.Photo: Fantasy Studios

The SSL E/G‑series and sync'ed Studer A800 MkIIIs used for the first mix in Fantasy's Studio D.Photo: Fantasy Studios

"After all the overdubs had been done in Studio B, I spent a couple of weeks mixing the record on the SSL in Studio D, running the two 24‑track tapes in sync. The guys told me, 'It's got to be dry, no reverb,' and even when I'd try to sneak it in here and there, they'd tell me to take it out. I certainly didn't record any effects, but I probably used some for monitor mixes for the guys to take home — reverb on the snare and toms, as well as a little on the vocal. I would use my AMS DMX15, and since Fantasy was a classic studio with a great collection of gear, it had some nice echo chambers upstairs. It also had an EMT 140 plate and an EMT 250 digital reverb; a big thing we used to call R2D2. It was like a space heater, about two feet high off the ground, really heavy, and it had these big levers that you'd push up and down. It worked great for really short reverb, giving it that non‑linear sound. Anyway, I used that gear as much as I could, but as soon as the guys heard anything or saw any lights working it would be, 'Oh, no reverb! All dry.'”

According to Billie Joe Armstrong, he and his colleagues did indeed want to create a dry sound "similar to the Sex Pistols' album or first Black Sabbath albums.”

"The tracks were such that you could just put the faders up and it sounded great,” Neill King continues. "But when I mixed the record everything had to be dry, with that really lo‑fi punk sound, and to be honest the whole thing sounded lifeless. You need a little presence here and there. With the two records that they'd done before on a little punk label in the Bay Area, it really didn't matter what they sounded like. But now they were of the ethos that punk records had to be bone dry, and after I mixed it they must have been persuaded by Warner Brothers [the parent company of Reprise] that it had to sound a little sweeter to get radio airplay. So they went down to LA, which is where Rob Cavallo is from, and had Jerry Finn mix the record with a little more reverb.”

Reception

'Basket Case' reached the Top 10 in the UK, received a Grammy nomination for Best Rock Vocal Performance By a Duo or Group, and spent five weeks at the top of the Modern Rock Tracks chart in the US, while Dookie received a Grammy Award for Best Alternative Music Album, peaked at number two on the Billboard 200, reached number 13 in the UK, and enjoyed some very positive reviews in the press. Time magazine named it the best rock album of 1994 and the New York Times gushed that "Punk turns into pop in fast, funny, catchy, high‑powered songs about whining and channel‑surfing; apathy has rarely sounded so passionate.”

Nevertheless, not all of the critics were so complimentary, some echoing the die-hard punks' assertion that Green Day had sold out, while Berkeley's renowned indie music club, 924 Gilman Street, endorsed that view by banning the group from playing there again after having signed with Reprise.

"In the middle of recording Dookie, they made their final appearance at 924 Gilman Street,” recalls Neill King. "That hole‑in‑the‑wall is basically where they came up, but the word had gone around that they'd signed with Warner Brothers and hardly anybody was there. It was amazing.”

For his part, in a 1999 interview with Spin magazine, Billie Joe Armstrong insisted, "I couldn't go back to the punk scene, whether we were the biggest success in the world or the biggest failure. The only thing I could do was get on my bike and go forward.”

Rob Cavallo certainly didn't have a problem with this attitude.

"My mantra as a producer at that time was 'I want you to sound like the best version of yourselves',” he subsequently recalled. "I think Dookie is a really good snapshot of what Green Day sounded like at that time. And that's why I think it works: because it's honest. That's not only why it works, but also why we didn't get killed. I didn't turn out to be the evil record producer who killed Green Day's sound.”

"It's a seminal record and it basically wrote the book on pop‑punk,” agrees Neill King who, since Dookie, has continued to produce and engineer bands on the West Coast and in Nashville, as well as in the UK, Australia and Canada. "It had nothing to do with the Sex Pistols or the Clash or punk in the classic sense, but with its big double‑tracked guitars and great tunes it became the blueprint for so many bands who came afterwards...”

SOS thanks Jeffrey Wood and Fantasy Studios for supplying the equipment photos featured with this article. www.fantasystudios.com

'Basket Case'

'Basket Case', which was released as the third single off Dookie following the chart success of both 'Longview' and 'Welcome To Paradise', would become one of Green Day's best‑known tracks: Billie Joe Armstrong's terse description of the anxiety attacks that he suffered before being diagnosed with a panic disorder. "Sometimes I give myself the creeps / Sometimes my mind plays tricks on me / It all keeps adding up / I think I'm cracking up...”

"The only way I knew how to deal with it was to write a song about it,” he has since explained. The promotional video pressed home this point by featuring Armstrong, Cool and Dirnt as inmates at a real‑life mental institution in Santa Clara County, California.

Starting with just Armstrong's vocal and guitar, 'Basket Case' introduces the rest of the band halfway through the first chorus, with Dirnt's bass line echoing the vocal melody while Cool provides an explosive edge via his rapid tom fills and quick‑fire transitions.

"That's such a great song,” Neill King remarks. "Like the rest of Dookie, it had a style that everybody copied, including Blink 182. The truth is, we were just doing what we would normally do, but it became a production style that a lot of people tried to imitate.”