Epic in every sense of the word — running to 21 songs, involving more than 120 musicians and taking almost two years to complete — Stevie Wonder's Songs In The Key Of Life was in many ways the high-point of an already illustrious career. This is the story of how it was created.

Photo: Steve Morley/Redferns"Just because a man lacks the use of his eyes doesn't mean he lacks vision," Stevie Wonder once said. And he set about proving this when, a decade after signing with Motown Records, he returned to the label in March 1972 and launched the second, halcyon phase of a career that had already seen him enjoy a US chart-topper at age 13 with 'Fingertips (Pt. 2)'; score further hits with the likes of 'Uptight (Everything's Alright)', 'I Was Made to Love Her', 'For Once in My Life', 'My Cherie Amour' and 'Signed, Sealed, Delivered I'm Yours'; and establish himself as a singer, songwriter and producer — all before his 21st birthday.

Photo: Steve Morley/Redferns"Just because a man lacks the use of his eyes doesn't mean he lacks vision," Stevie Wonder once said. And he set about proving this when, a decade after signing with Motown Records, he returned to the label in March 1972 and launched the second, halcyon phase of a career that had already seen him enjoy a US chart-topper at age 13 with 'Fingertips (Pt. 2)'; score further hits with the likes of 'Uptight (Everything's Alright)', 'I Was Made to Love Her', 'For Once in My Life', 'My Cherie Amour' and 'Signed, Sealed, Delivered I'm Yours'; and establish himself as a singer, songwriter and producer — all before his 21st birthday.

Comeback

Arguments over creative control had led to a rift with Motown, and when Wonder returned it was on his own terms. Thus commenced an incredible four-year stretch during which he released five classic albums that would define his artistic legacy: Music of My Mind, Talking Book, Innervisions, Fulfillingness' First Finale and his magnum opus, Songs In The Key Of Life, an expansive two-album-plus-EP set that displayed the breadth and depth of Wonder's talents.

Packed with a greatest-hits-calibre collection of tracks, from the infectious energy of 'I Wish', 'Sir Duke', 'Contusion' and 'Isn't She Lovely', through the social commentary of 'Love's In Need Of Love Today', 'Village Ghetto Land', 'Black Man' and 'Pastime Paradise' to the euphoric liberation of 'Ngiculela — Es Una Historia — I Am Singing', Songs In The Key Of Life was Stevie Wonder's masterpiece. Not only was the material of a uniformally high standard, but the vocal performances were among his very best. While the jazz-funk-pop fusion arrangements were, to say the least, highly ambitious, even if some critics considered them self-indulgent, thanks largely to the main man's frequent reluctance to end a song without an extended jam-based outro, his many fans didn't complain.

'I Wish' and 'Sir Duke' (a tribute to the recently departed Duke Ellington and other musical heroes) both topped the American pop and R&B charts; 'Isn't She Lovely', which celebrated the birth of Wonder's daughter Aisha, quickly became a standard (and a UK Top 10 hit for David Parton); and 'Pastime Paradise', a meditation on those who live in the past with little hope for the future, would be sampled and reworked by West Coast rapper Coolio into the 1995 Grammy-winning smash hit 'Gangsta's Paradise', a US and UK number one that was itself parodied by 'Weird Al' Yankovic's 'Amish Paradise' the following year. 'Pastime Paradise' is, consequently, among Stevie Wonder's best-known and most successful compositions, his own version being distinguished by its Krishna-sect/gospel group backing vocals and unabashed playing of synthesized strings, as well as the politically charged Bicentennial-year lyrics.

"I remember, when he was writing that song in the studio, he was struggling to come up with all of those '-tion' words like 'dissipation', 'segregation', 'exploitation'," says Gary Olazabal, who, shortly after starting out as a gofer at LA's Record Plant, served as a tape-op on Innervisions, assisted on Fulfillingness' First Finale and then launched his career as a full-fledged engineer with Billy Preston, Rufus & Chaka Khan, and Stevie Wonder's Songs In The Key Of Life on the way to repeating that role on most of Wonder's subsequent albums. "He was trying to come up with enough of those lyrics that would actually mean something and make sense."

And he did, for the song's two bridge sections: "Tell me who of them will come to be, How many of them are you and me. Dissipation, race relations, consolation, segregation, dispensation, isolation, exploitation, mutilation, mutations, miscreation, confirmation, to the evils of the world... Proclamation, of race relations, consolation, integration, verification, of revelations, acclamation, world salvation, vibrations, stimulation, confirmation, to the peace of the world."

And he did, for the song's two bridge sections: "Tell me who of them will come to be, How many of them are you and me. Dissipation, race relations, consolation, segregation, dispensation, isolation, exploitation, mutilation, mutations, miscreation, confirmation, to the evils of the world... Proclamation, of race relations, consolation, integration, verification, of revelations, acclamation, world salvation, vibrations, stimulation, confirmation, to the peace of the world."

Crystal Sounds

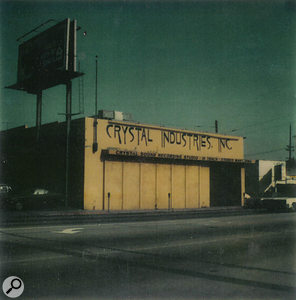

Olazabal, meanwhile, actually co-engineered Songs In The Key Of Life with John Fischbach, the owner of Crystal Sound in LA, where the vast majority of the album was recorded over the course of about two and a half years, in addition to the Record Plants in Los Angeles and Sausalito, and the Hit Factory in New York. In between, there was a trip to Jamaica to record the backing for a song that ultimately never made it. At the end, there was a return to Crystal for the mix.

"Almost everything that was recorded at Crystal over the course of three or four years turned into a hit," says Fischbach, who originally encountered Stevie Wonder at New York's Electric Ladyland in about 1971, and then had him record at Crystal a couple of years later. "I'd produced Carole King's Writer album there, and then became partners in the studio with its owner, Andrew Berliner, who was an electronics genius, a classically trained pianist and one of the world's great engineers. We were prepared, but we also had a lot of good luck, working not only with Stevie but with James Taylor, Jackson Browne, War, REO Speedwagon, the Jackson 5, the Miracles, Marvin Gaye — the list was truly unbelievable.

Crystal Sound Studios in Los Angeles, where the majority of work on Songs In The Key Of Life was completed.Photo: Steve Morley/Redferns"It was a great transition period back then, with younger musicians and artists no longer wanting to use the record labels' own studios. Columbia, RCA and Capitol all had terrific facilities, but they also had the older union engineers who worked specific hours and wouldn't let a producer move a microphone or touch a tape machine. Well, young people didn't want to play by those rules any more. They wanted to act young and get away with it, and as one of the first independent studios Crystal was able to fill that niche."

Crystal Sound Studios in Los Angeles, where the majority of work on Songs In The Key Of Life was completed.Photo: Steve Morley/Redferns"It was a great transition period back then, with younger musicians and artists no longer wanting to use the record labels' own studios. Columbia, RCA and Capitol all had terrific facilities, but they also had the older union engineers who worked specific hours and wouldn't let a producer move a microphone or touch a tape machine. Well, young people didn't want to play by those rules any more. They wanted to act young and get away with it, and as one of the first independent studios Crystal was able to fill that niche."

"Stevie really liked Crystal," recalls Gary Olazabal, "and so it was just kind of thrust upon me one day: 'Show up at Crystal... This is John. You guys are gonna be working together.' As things turned out, he and I tag-teamed, got along really well and never had a disagreement. I would do the recording and punching-in on one thing, and then he'd take over, and vice-versa. Listening to the album now, I can't tell you who did what. I mean, if one of us was in the middle of recording something and needed to have a break, the other would take over and continue doing exactly the same job. We both had our favourite songs that we liked to work on, but there never was a point where one of us did everything on one song."

Aside from a lone exception. "Nobody thought this project would go on as long as it did," says Fischbach. "Gary had made an arrangement with another group to engineer their album, and he couldn't get out of it, so during the time he did that I worked alone with Steve at the Hit Factory in New York for about a month and a half. We worked on just one basic track — I can't remember which — and that was it. Otherwise, it was all Gary and I, and virtually the entire album was done at Crystal."

The setup at Crystal comprised a home-made 32-input console, George Augsberger monitors, two Studer 24-track machines, three Studer two-tracks and an array of new and vintage microphones.

"The console was custom built by my partner, Andrew, and we even had a 3D circuit, which was great," says John Fischbach. "It was like a reverse Fletcher Munson curve, so we could actually move something back in the mix just by turning this knob. It had a particular EQ curve on it, and the more you turned it, the deeper this curve got, and it moved things back. The bass would stay up a little bit but the treble would go off, off, off, off, off, and then the bass would would start to roll off, too. It was fantastic. It had great equalisers, really great mic preamps, and there was a whole separate monitor section.

"Some of the best mixes I ever did came through that monitor section. We had a pan pot, a fader and an echo send on each tape return, but it was a pure path. There was no EQ, it didn't go through extra amplifiers, and so some of the mixes we'd get off that couldn't be reproduced if we moved to the main console, where the EQ was. I remember using that monitor mixer to do a rough mix of 'Love's In Need of Love Today' at about three in the morning, and although we tried countless times to mix that song again when we were getting ready to mix the album, we ended up using the monitor mix because we could never beat it.

"Crystal was one of the first facilities to use Dolbys and have all-Studer machines, and the first to have an EMT 250 reverb. That unit cost $20,000, which was a lot of money back in 1973. And then there were the Augsberger monitors, each the size of a small project studio. They were huge, and boy, we could play 'em loud. In those days, that's what you did: turn 'em up."

Additional Personnel...

Wonderlove, the band that Stevie toured with, made up the core rhythm section for the Key Of Life sessions: drummer Raymond Pounds, bassist Nathan Watts, Michael Sembello playing lead guitar, Ben Bridges on rhythm guitar, saxophonist Hank Redd and percussionist Ray Maldonaldo.

"There were plenty of session guys, and Stevie would also bring in a lot of guest stars throughout the recording process," says Gary Olazabal. "Some of them would just come in to say 'Hi' and end up playing on the record."

Stevie Wonder and Gary Olazabal in Wonder's Wonderland Studio, 1986.Photo: Steve Morley/RedfernsGeorge Benson, Herbie Hancock, Minnie Riperton, Deniece Williams, Stevie's ex-wife Syreeta Wright — these were just a few among the more than 120 musicians, many of them vocalists, who have been credited with contributing to the album; including, as already mentioned, the Krishna devotees who sang backup on 'Pastime Paradise'.

Stevie Wonder and Gary Olazabal in Wonder's Wonderland Studio, 1986.Photo: Steve Morley/RedfernsGeorge Benson, Herbie Hancock, Minnie Riperton, Deniece Williams, Stevie's ex-wife Syreeta Wright — these were just a few among the more than 120 musicians, many of them vocalists, who have been credited with contributing to the album; including, as already mentioned, the Krishna devotees who sang backup on 'Pastime Paradise'.

"Gary rounded them up on Hollywood Boulevard," John Fischbach recalls. "We had decided it would be great to have them on the song, so he went and talked to a bunch of those people and made arrangments for them to come to the studio."

"Crystal was located on the east side of Hollywood," says Olazabal, "and they walked in line all the way from the Self-Realization Fellowship. There must have been about a hundred of them, chanting and praying as they showed up to perform on the song, but Stevie never showed up. We didn't know what to do, and so we just let them go into the studio. The main room was not very live-sounding, but it was very big. Well, they were in there for hours, chanting — they didn't really interact much in any other way — and when Stevie didn't appear we knew they'd have to walk all the way back and return another day."

At least there was little chance of a fight breaking out. "There was not a lot of hostility," Olazabal agrees, "except from us. It wasn't easy to listen to that chanting for hours on end."

The Dream Machine

Whenever Wonder is ready to work, his methods are, according to Olazabal, "frighteningly spontaneous. When he starts writing a song, he can hear its entire production as a finished piece in his mind. Obviously, this changes as the song develops, but in his mind he hears the finished master. Initially, sitting at the keyboard, he doesn't have a lyric. So he might come up with a hook or an idea for the chorus, and then everything will flow from there."

"He has a better grasp of what he's trying to accomplish than anyone else I've ever worked with," says Rob Arbittier, a keyboard player who began working with Stevie Wonder as a programmer in 1985 and five years later launched a company called Noisy Neighbors Productions with Olazabal, writing and producing music for TV commercials and movie trailers, while also taking care of any sound design required.

The Yamaha GX1 'Dream Machine' used to great effect on 'Pastime Paradise'.Photo: Steve Morley/Redferns"And while he might not always express it in a real obvious, logical way, he knows when he hears through his ears what he's hearing in his mind, and he knows how to steer something toward what he wants it to be. He has an unbelivable understanding of what the technology can do, and that's why he's always pushing it beyond its stated limits. When he hears a device make a certain sound, he has a good idea of what other sounds it could make, and he likes to push that envelope. Since he isn't interested in the manual or sitting through a flashy demo at a NAMM show, he doesn't know what the technology is supposed to be able to do. He just knows what he's hearing it do and what he thinks it could do next."

The Yamaha GX1 'Dream Machine' used to great effect on 'Pastime Paradise'.Photo: Steve Morley/Redferns"And while he might not always express it in a real obvious, logical way, he knows when he hears through his ears what he's hearing in his mind, and he knows how to steer something toward what he wants it to be. He has an unbelivable understanding of what the technology can do, and that's why he's always pushing it beyond its stated limits. When he hears a device make a certain sound, he has a good idea of what other sounds it could make, and he likes to push that envelope. Since he isn't interested in the manual or sitting through a flashy demo at a NAMM show, he doesn't know what the technology is supposed to be able to do. He just knows what he's hearing it do and what he thinks it could do next."

According to Olazabal, Wonder is always interested in obtaining equipment that nobody else has. "Stevie's still trying to get the next new thing," he says. "He's just like a kid that way."

"And a lot of times, as soon as something starts working reliably, he loses interest," Arbittier adds. "I mean, through the years we've experimented and come up with the craziest technology and ideas, but as soon as the stuff is working fine, Stevie will say, 'OK, well, what's next?' Like when DSD recording finally became stable for stereo, he immediately said, 'Now we need a multitrack.' It's never-ending, and that continues to this day. On the other hand, one of the things people lose sight of, if they think of Stevie as primarily a technology person, is that all of this technology would have been meaningless if the songs hadn't been so great. There have always been plenty of people experimenting with sounds, but it's when you marry such amazing songs with the best technology that you have the recipe for a true classic."

In the case of 'Pastime Paradise', a Yamaha GX1 served as the starting point. A huge and powerful polyphonic analogue synthesizer, with chrome pedestals and a curved metallic body, the GX1 — introduced in 1973 as a forerunner to their CS80 — housed three keyboards, a pedal-board, a ribbon controller that produced modulation changes, two swell pedals and a spring-loaded knee controller, along with a variety of buttons and switches to program, store and recall sounds. The top three-quarter-scale, three-octave, 37-note keyboard had half-size keys and offered unprecedented touch control; the other two five-octave, 61-note standard-size keyboards were equally functional, with horizontal position control enabling the player to achieve effects such as vibrato by moving the keys side-to-side.

Since the GX1 was invented as a test-bed for later consumer synths, only a few were built, and among the purchasers were Keith Emerson of ELP, Led Zeppelin's John Paul Jones and Stevie Wonder, who quickly labelled it 'The Dream Machine' and employed it innovatively on Songs In The Key Of Life, by way of some highly expressive string sounds on both 'Village Ghetto Land' and 'Pastime Paradise'.

"Stevie started getting into more classical sounds," says Gary Olazabal. "He and Greg Phillinganes were both just fooling around, playing a lot of classical chord progressions, and the melody of 'Pastime Paradise' was based on the string sounds that he was getting. In fact, we recorded the Dream Machine as if it was an actual string section, with Stevie playing the cello part, the violas and so on. It had these monolithic speaker cabinets, and we would tilt them toward the ceiling and place overhead mics far away — either AKG 414s or Group 128 419s — capturing it as though it was a stringed instrument. We combined this with DI for some presence, but basically we tried to treat it like an instrument in its own right.

"Sometime later, we were at the Record Plant up in Sausalito, and we played the song for a legendary recording artist whose name I won't mention because I don't want to embarrass him. He asked Stevie where we did the strings, and Stevie replied that we'd used the London Philharmonic. Well, this guy believed him, and Stevie and I were giggling because we'd put one over on him, until eventually he figured out what was happening and left the studio, never to be seen again. I still feel embarrassed about that. It was like, 'OK, Steve, let him off the hook,' but he wouldn't."

Credits: Deserved & Undeserved

A pair of Stephen St.Croix's Marshall Time Modulators.Photo: Steve Morley/Redferns Although the Marshall Time Modulator — a unit with custom integrated circuits that produced effects such as delay, flanging, double-tracking and vibrato — was utilised on tracks such as 'All Day Sucker', its inventor Stephen St. Croix did not, contrary to a myth that he himself perpetrated, play guitar on the track, and neither did he host Stevie Wonder in his own home for six months so that they could work together on Songs In The Key Of Life.

A pair of Stephen St.Croix's Marshall Time Modulators.Photo: Steve Morley/Redferns Although the Marshall Time Modulator — a unit with custom integrated circuits that produced effects such as delay, flanging, double-tracking and vibrato — was utilised on tracks such as 'All Day Sucker', its inventor Stephen St. Croix did not, contrary to a myth that he himself perpetrated, play guitar on the track, and neither did he host Stevie Wonder in his own home for six months so that they could work together on Songs In The Key Of Life.

"That would have never happened," says Gary Olazabal. "What he actually did was hang out at a lot of the recording studios that we used, pushing his Time Modulator, and it was a pretty cool piece of equipment. However, Stevie did not work on the album at his home, and Stephen St. Croix did not co-produce or engineer it, as I've read somewhere. I tell you, more people have supposedly recorded that album than have slept with Marilyn Monroe."

Born Stephen Curtis Marshall, St. Croix — who took his name from the Caribbean island that he loved — founded Marshall Electronics, designed the first true stereo Real Time Analyser and redesigned the interface for the Quantec Room Simulator. Sadly, he died of skin cancer at age 58 in 2006.

"I would love to have a Marshall Time Modulator now," John Fischbach remarks. "That was the greatest double-tracking device ever made. Nothing has ever come close to it, and for that he was a genius, but all of the other stuff about his work on the album is absolute nonsense. The same with the Hit Factory. When the owner died, his obituary stated that Songs In The Key Of Life had been recorded at his studio. And when the studio went under, his son said the same damned thing, but it just wasn't true.

"Aside from a few bits and pieces, the stuff that ended up on the record was done at Crystal, and Gary and I were the only engineers, along with Dave Henson, who was the assistant engineer there. Dave was phenomenal. He was the one who aligned the machines, and if you go to any of the tapes from all the time that we did the album, there's not more than a quarter of a dB difference on any of them. He was really, really great, and so he's someone who should be getting some well-deserved credit."

Microphones

Unlike many of the other songs, 'Pastime Paradise' didn't use a live rhythm section. Instead, assembled piecemeal, its synth strings were supplemented by percussion courtesy of Ray Maldonado and Bobbye Hall, with finger cymbals playing a vital role, while Wonder utilised a clapboard for the snare backbeat. In addition, he also contributed a keyboard bass part, before recording the main vocal and then having the song's closing section adorned with backing singers in the form of the aforementioned Krishna devotees and a separately recorded gospel group.

"The one important thing that we did at the Record Plant in Sausalito was the backward gong on 'Pastime Paradise'," says John Fischbach, who since 2000 has been running Piety Street Recording in New Orleans. "It took us forever to do that. We had to turn the tape upside down, and we also had to figure out where we were going to hit the gong so that, when it was turned around, the gong went backward in the right place, actually peaking where we wanted it to end. That was just a matter of trial and error, over a period of several hours. But you know, one of the great things about doing this album, and one of the things that I will always be grateful for, was the freedom that Gary and I had to do whatever we wanted to do. If we thought turning a cymbal over and filling it with nuts and bolts would be cool, we'd just do it. And if we thought a song would be better if we re-recorded it, we had that luxury. It was a great, great experience, and later on people wouldn't be allowed that kind of freedom."

GX1 voices were programmed onto matchbox-sized cartridges. Each cartridge had 26 screw-sized dials on it to change the VCO, VCF, VCA and envelope of the voice. Seventy cartridges in total were loaded into racks that emerged from the top of the console. Rob Arbittier demonstrates how the GX1 modules are inserted.Photo: Steve Morley/RedfernsFor extra presence, an AKG 414 was used to record the percussion on 'Pastime Paradise', yet overall the sound of the song was extremely dry, and this included Wonder's vocal, since he wanted it to match the stark lyrical content.

GX1 voices were programmed onto matchbox-sized cartridges. Each cartridge had 26 screw-sized dials on it to change the VCO, VCF, VCA and envelope of the voice. Seventy cartridges in total were loaded into racks that emerged from the top of the console. Rob Arbittier demonstrates how the GX1 modules are inserted.Photo: Steve Morley/RedfernsFor extra presence, an AKG 414 was used to record the percussion on 'Pastime Paradise', yet overall the sound of the song was extremely dry, and this included Wonder's vocal, since he wanted it to match the stark lyrical content.

"He wasn't being preachy," says Olazabal. "He just didn't want the song to sound too light. So, aside from a little reverb, the vocal was fairly in-your-face and we recorded him sitting at the keyboard, using a Sony C500. We changed his vocal mics all the time, tailoring the sound to each song, and he knew how to work a microphone. He was, for example, fond of using an Electrovoice RE20 on more aggressive songs like 'I Wish', whereas we'd use more transparent mics on ballads."

"There was a hi-tech company named Group 128 that manufactured radio telescopes, and one of the engineers there came up with a little electric microphone called a 419Z," adds Fischbach. "A friend of mine in LA who owned a stereo store asked me if I wanted to try it. The mic consisted of a 10-inch aluminum tube that was about an eighth of an inch in diameter, and it had a tiny gold capsule at the end, along with a little power supply and volume knob. I told my friend, 'I don't think so,' and he said, 'Oh, come on. The guy wants me to carry these. Why don't you try it?' Well, I was going to New York to work with Stevie [at the Hit Factory], and so the first thing we tried it on, just as a favour to my friend, was acoustic guitar. It was an omnidirectional microphone, and as soon as we heard what it could do our mouths dropped open. That mic was unbelievable. We even ended up using it on Stevie's vocals — if you listen to 'Village Ghetto Land', you can hear him wagging his head between two of them.

Photo: Steve Morley/Redferns"Years later, we tracked down the engineer responsible for the 419Z. He had four capsules left, and so he made us four microphones and they were really amazing. If you just rubbed two fingers in front of them it sounded like sandpaper. Those mics were amazing on piano, vocals, you name it. In fact, the weird horn on 'Sir Duke' came from miking the horns in front as you normally would, but then also having the 419s behind them. They were phenomenal.

Photo: Steve Morley/Redferns"Years later, we tracked down the engineer responsible for the 419Z. He had four capsules left, and so he made us four microphones and they were really amazing. If you just rubbed two fingers in front of them it sounded like sandpaper. Those mics were amazing on piano, vocals, you name it. In fact, the weird horn on 'Sir Duke' came from miking the horns in front as you normally would, but then also having the 419s behind them. They were phenomenal.

"On some songs we used a [Neumann] 87 for Steve's vocals, a lot of times an RE20 worked out really well for him, and there was also a Telefunken 47 that he tried and didn't like all that much but which we did use for his harmonica."

"It can sometimes be kind of a shocker when Stevie sings dynamically, with extreme highs and lows," Olazabal remarks. "But since the vocal sessions are very rarely short, even during warm-ups there's plenty of time to get it right. Then, when everything's good to go, you have to be real sure that his first take is well recorded, because he'll often return to parts or all of it after ten billion other attempts, when he's been unable to recapture that original emotion.

"In the old days, before Pro Tools, Stevie's vocals could take a really long time. He'd want to keep punching in esses, and he'd just give me a head-nod or an eyebrow-twitch and I'd have to be ready. We didn't do comps. He'd do a lot of different takes until he found one that he liked, and then we would fix that, word by word, syllable by syllable. I don't know how his voice stood up for all those hours, but it did, and it still does. He still operates the same way, as far as I know, and his voice still sounds amazing. He himself loves to hear it, and while that's refreshing, when you get to the mix there does have to be a compromise between the level of the voice and hearing the track. That's not always easy when you're working with an artist who has a voice that you don't want to hide."

Songs In The Key Of Late

Time-keeping seems to be a recurring theme when discussing Stevie Wonder's recording process — his tardiness is nearly as legendary as his talent.

"There can definitely be frustrations working with him, yet I've also never met another artist who can make you forget about these so easily," says Olazabal. "He can keep people waiting for hours or days, and then he'll show up and they'll immediately forget about it."

"That's a really annoying ability," adds Rob Arbittier. "He knows when he finally gets there it'll be worth the wait, whether that's because the music is great or he's just such an engaging personality.

"I remember, Gary and I were working in the mobile truck on the album Characters [1987]. By that time, we were a team and I was very comfortable with the whole process. We'd work on stuff, and when we had something for Stevie to hear, we'd go get him out of his office, play it for him and then the three of us would interact. We had a really good working relationship. However, there was one point where Gary and I were working on something at the studio and Stevie came out of his office and said, 'You guys keep working. I've got to run an errand. I'll be right back.' We didn't think anything of it. He got into a car with his driver and left, we worked for a while, a few hours went by and finally his driver came back to the studio. We said, 'Where's Steve? Is he with you? We've got some stuff we have to play him.' The driver said, 'Well, I just dropped him off at the airport. He's on his way to Africa.' Gary and I looked at each other — there didn't need to be any dialogue. He was gone for about six weeks!"

"It was like he expected us to be working in that little truck while he was gone all that time," Olazabal adds, while Arbittier remarks, "I think he liked to act as if he expected everyone to be there. However, he didn't really expect that. I'm sure he knew the moment we got the word, we'd do our own thing. It was those kinds of sessions that led to Gary and me forming our own company."

Given Wonder's fondness for middle of the night start-times, Olazabal quickly learned to not bother rushing to the studio unless SW was actually there.

"In the beginning it sucked for me," Arbittier adds. "I was the new guy and I was all gung-ho, so when Stevie said he'd be there at 7pm I'd get there at 7pm, all excited, and then wait until four in the morning for him to arrive. By then, I'd be completely burned out, Stevie and the guys would feel fresh, and they would then call Gary, who'd come down five or ten minutes later. Eventually, I became crotchety enough to tell the studio, 'When Steve gets there, call me.' I didn't live that far away, so I could get there before he was ready to work."

As for Stevie being kept waiting — "Oh, he's pretty impatient," asserts Olazabal.

Consolation, Integration... Compilation

Songs In The Key Of Life was compiled by simultaneously using three tape machines: two of them for the pair of two-track tapes and another for the final stereo mix, as performed by Gary Olazabal and John Fischbach, sitting together behind the console in Crystal Sound.

"We would put song one on one stereo two-track and song two on the other," Olazabal explains. "So as song one was fading out, we'd start song two from the other two-track at the right time, enabling them to crossfade with the proper rhythm. When you now listen to the album, you can't imagine the work of these people who were biting their nails, especially when we'd get to the last track, hoping we could start the machine in time. I mean, you could make it all the way to the last song, but if you failed to press 'play' when you were supposed to it wouldn't have been pretty. Then again, that was part of the excitement, whereas now people don't even have to think about assembling an album with crossfades.

Gary Olazabal, pictured in Wonderland, 2007. Behind him you can see Stevie's Moog Modular system and Rhodes piano.Photo: Steve Morley/Redferns"We didn't mix until the final stages, because there was so much material recorded that we had to get a run-down of all the songs. There was a democratic process where everyone voted for their favourite tracks, but then Stevie threw that all out and selected what he wanted anyway. That's why there was an EP — he couldn't even fit some of the songs onto a double album, but they were important enough that he wanted them to be included in the package. So, we didn't do the formalised mixing until the final stages of the project. It was a marathon, and at times we wondered if it would ever finish. We had T-shirts with 'Are We Finished Yet?' printed on them, as well as others with 'Let's Mix 'Contusion' Again'. Without exaggeration, we must have mixed that track at least 30 times. It became part of the joke of our lives."

Gary Olazabal, pictured in Wonderland, 2007. Behind him you can see Stevie's Moog Modular system and Rhodes piano.Photo: Steve Morley/Redferns"We didn't mix until the final stages, because there was so much material recorded that we had to get a run-down of all the songs. There was a democratic process where everyone voted for their favourite tracks, but then Stevie threw that all out and selected what he wanted anyway. That's why there was an EP — he couldn't even fit some of the songs onto a double album, but they were important enough that he wanted them to be included in the package. So, we didn't do the formalised mixing until the final stages of the project. It was a marathon, and at times we wondered if it would ever finish. We had T-shirts with 'Are We Finished Yet?' printed on them, as well as others with 'Let's Mix 'Contusion' Again'. Without exaggeration, we must have mixed that track at least 30 times. It became part of the joke of our lives."

Released on September 28, 1976, Songs In The Key Of Life debuted atop the Billboard 200 album chart, remained there for a record-breaking 14 weeks, and went on to sell more than 10 million units in the US alone, earning an RIAA Diamond Award in 2005 for its 10-times Platinum certification. At the 1977 Grammy show, it scooped the awards for 'Best Male Pop Vocal Performance' and 'Album of the Year', while 'I Wish' won for 'Best Male R&B Vocal Performance'.

"That is a very broad statement," Stevie Wonder commented shortly afterwards, referring to the album's title. "And I think if I can just accomplish one fraction of an iota of that, dealing with life, my life, and the lives of the people who hear the album, I'll be very happy."

By the age of 26, he had done his best to justify the genius tag bestowed on him by Motown some 14 years earlier, winning the 1973, 1974 and 1976 Grammy Awards for 'Album of the Year' that culminated in what Rolling Stone has described as "the crowning achievement of '70s pop's grand aspirations," and marked the career high-point of a remarkably precocious musical talent.