The story of how a characteristically chaotic and unorthodox recording session took Ian Dury & The Blockheads to the top of the charts.

Ian Dury performing on Top Of The Pops, 1978.

Ian Dury performing on Top Of The Pops, 1978.

Aa graduate of the Royal College of Art and a feature on London's pub-rock scene as frontman with Kilburn & the High Roads during the early '70s, Ian Dury carved out a niche for himself later in the decade courtesy of his unorthodox appearance, in-your-face attitude, uncompromising Cockney-accented vocals and a bizarrely eclectic musical melange of pop, punk, jazz and disco.

Contemporary and traditional, Dury's best songs — written mostly in conjunction with keyboardist/guitarist Chaz Jankel — blended a hypnotic beat with humorously edgy observations of everyday life. Yet these, together with the clearly enunciated local vernacular and omnipresent music-hall influences, contrived to make the material idiosyncratically British. And accordingly, while songs such as 'What a Waste' and 'Reasons to Be Cheerful (Part Three)' were Top 10 hits in the UK, their success was limited elsewhere. Ditto 'Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick', which went all the way to number one in January 1979. This song was, in short, the pinnacle of Ian Dury's career.

The Workhouse

Just over two years earlier, Dury had collaborated with both Jankel and Steve Nugent on the tracks that would end up on his debut solo album, New Boots and Panties!! Demos were then recorded at Alvic Studios in Wimbledon in April 1977, with Dury singing and playing drums while Jankel took care of bass, guitar and piano, and it was during those sessions that Dury was introduced to the bassist, Norman Watt-Roy, and drummer, Charley Charles, who would play on the album and subsequently become members of his band, the Blockheads.

A week after the demos were completed, all four began recording at The Workhouse on London's Old Kent Road, which was co-owned by Manfred Mann and Dury's management company, Blackhill Enterprises, and thus made available to the unsigned musicians at no real cost when it wasn't being used, usually late at night. Three men shared the production chores: Pete Jenner, Rick Walton and Laurie Latham, while Latham also engineered behind what he now describes as "the best API board I've ever worked on. I've worked on a few in the States and in London, but none of them were as good as that one. It was brilliant; a really big desk with great EQ. I seem to remember the routing was a bit odd — there weren't many routing switches, so you had to patch out of about eight busses — but otherwise I loved everything about it.

"The studio didn't have much gear: a Studer 24-track machine, great big JBL 4341 monitors, a Pye compressor and some Audio & Design bits and pieces, but not a lot else. The control room looked down on the live area — a bit like a mini Trident — with a lift at one end to take the equipment down into the studio. Well, of course that was a nightmare for poor old Ian, because he had to get up and down the stairs [Dury had been affected by polio at age seven]. Really, it was the worst place in the world for him to work, so he'd just stay down in the studio, sitting on his stool and listening back though headphones. He'd only come into the control room if he really wanted to check something, and when he did he'd usually wind-up the production team."

More of which later...

Sex And Drugs And Rock & Roll

An art student and part-time musician, Laurie Latham entered the studio business in 1973 as an assistant at Maximum Sound — as The Workhouse was then known — where he subsequently recorded Manfred Mann's Earth Band, which enjoyed a US chart-topper in February of 1977 with 'Blinded By The Light'. Shortly afterwards, he actually went after some work in America, but was enticed back to The Workhouse when it was part-purchased by Blackhill, whose roster of artists interested him. Not that Laurie Latham knew all that much about Ian Dury before New Boots and Panties!! launched his production career.

"I got a call from Peter Jenner," Latham recalls, referring to the man who was Andrew King's partner in Blackhill, the company that had managed Pink Floyd, Syd Barrett, Marc Bolan, the Clash and Roy Harper (whom Jenner had also produced). "He said they were bringing in this character on their books named Ian Dury, who I knew vaguely from Kilburn & the High Roads, and he turned up with this carrier bag full of lyrics, and the first thing we did was 'Sex And Drugs And Rock & Roll', which turned out to be a single."

At a time before Michael Jackson had rendered stand-alone singles virtually obsolete, Ian Dury preferred his own singles to be omitted from albums. Therefore, 'Sex And Drugs And Rock & Roll', which was not a hit, didn't find its way onto original pressings of New Boots and Panties!!

At a time before Michael Jackson had rendered stand-alone singles virtually obsolete, Ian Dury preferred his own singles to be omitted from albums. Therefore, 'Sex And Drugs And Rock & Roll', which was not a hit, didn't find its way onto original pressings of New Boots and Panties!!

"That song was recorded with hardly any equipment," Latham says. "Chaz played his Gibson ES335 through my little Selmer amp, which had a blown speaker — that's what you hear the 'Sex And Drugs' riff going through — and Peter Jenner and I were behind the desk, nursing the whole thing along."

Saxophonist and former Kilburn High Roader Davey Payne was recruited to supplement the line-up for the album sessions, as were guitarist Ed Speight and Moog player Geoff Castle, and all were quick to learn Chaz Jankel's carefully demo'd arrangements. Meanwhile, although the aforementioned trio of Jenner, Latham and Walton would be widely recognised as the record's producers, its technical credits wouldn't reflect this.

"Back then the punk ethics were still in full swing and it was pretty un-cool to admit you had a producer," Latham explains. "Then again, I'm not on royalties for New Boots, while Rick Walton, who was one of the producers, only did a couple of things when I wasn't around. For his part, Peter would sit there rolling joints all day and I'd do all the bloody work, but in fairness I also have to say that he taught me an awful lot. He wasn't particularly hands-on, but he would always say things like, 'Laurie, are you sure the bass drum's loud enough? Maybe you should nudge it a bit.' It was always the bass drum or the bass, and if you think about it, the rhythm section is what really defines that record.

"Obviously, there's Ian and his lyrics, but people also talk about how brilliant Norman and Charley were. Well, Peter was brilliant, too, and I think he was really undervalued in the end. He recognised that the bass drum and bass were potent, very integral ingredients of the overall sound — the idiosyncratic, mad Cockney-type thing on top of this quite slick, funky sort of rhythm section. And he was also very good at making sure that Ian was on the ball in terms of his vocals. After all, what with his sometimes unconventional phrasing, there were times when things could get pretty strange rhythmically. I would spend hours and hours on the vocals, as well as getting the headphones right. He was very demanding and his voice had to be really loud in the cans — after all, if you're having trouble performing a track, the first thing you do is whinge about the cans, isn't it? You know, 'I haven't got enough vocal,' 'Something's not right with the mix,' or 'I'm not in tune because of something or other.' The fact is, you've just got to get on with it."

Stiff Records & The Birth Of The Blockheads

Even at a time when punk was opening record company doors to artists who wouldn't have managed so much as a look-in a couple of years earlier, Ian Dury's management was unable to find a label that would release their maverick's album. That was, until Stiff Records just happened to lease office space directly below Blackhill's. Elvis Costello and the Damned were already on Stiff's books. A licensing deal meant Dury would be next, and following its release on September 30th, 1977 — hot on the heels of 'Sex And Drugs And Rock & Roll' — New Boots and Panties!! gained critical plaudits and popular recognition in the UK, where it stayed on the charts for two years and was eventually certified platinum. (In America it was a different story — despite great reviews, the album tanked and Arista immediately dropped Ian Dury.)

That October, in support of the record, Dury participated in the Live Stiffs package tour with Elvis Costello and the Attractions, Nick Lowe, Wreckless Eric and Larry Wallis, and for this he and Chaz Jankel formed the Blockheads with Norman Watt-Roy, Charley Charles, guitarist John Turnbull and pianist Mickey Gallagher. The tour was a success and Stiff's marketing campaign helped the band's next single, 'What a Waste', go Top 10, yet with the extra personnel there came a change in dynamics that was evident as soon as Dury and his Blockheads re-entered The Workhouse to record 'Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick'.

"For me, in the studio, it isn't about recording what people do live," says Laurie Latham, "but everybody collaborating and working together, surrendering to the whole studio concept to create something larger than life. That was the case when we did New Boots and 'What a Waste' — it was a small team, with me and Peter producing. But then the Blockheads were formed and everyone was chipping in, and I remember with 'Hit Me' everybody turned up on the first day and it was bloody chaos in the studio, with all of them talking at once and equipment everywhere. They'd just come back off the road after doing an English tour, and everything was attuned to the road rather than the studio. The attitude towards me was along the lines of, 'Well, you're the bloke who records it, so you sort it out.'"

A song with sexual overtones, smatterings of French and German, geographical references and, according to Dury, a message of non-violence, 'Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick' was written by him some three years before he realised it was worthy of recording. At least, that's what he claimed. Guitarist John Turnbull has stated that the lyrics were written just six months earlier, while the Blockheads were touring the States, and that once in the studio Dury was still making changes, replacing "it don't take arithmetic" with the far more potent "it's nice to be a lunatic".

Either way, what nobody disputes is that the music, inspired by a piano part towards the end of New Boots ' opening track, 'Wake Up and Make Love With Me', was composed during a Jankel-Dury jam session at a rented mansion in Rolvenden, Kent, and that Dury then showed Jankel his lyrics that very same afternoon. Thereafter, the rest of the Blockheads were involved in the routining, and Norman Watt-Roy distinguished both the song and himself by way of a stunning bass line played 16 notes to the bar.

"I think Norman had just been to see Jaco Pastorius at the Hammersmith Odeon," says Latham, "and that's where he got the idea to play like that."

Strange Reflections

Perhaps that's often more easily said than done — working with a rhythm section that consisted of five guys thrashing away together in a live area that lived up to its name courtesy of a high ceiling covered in metal tiles? Not easy.

"You got a really strange reflection in certain parts of that room, and it was a bit of a pain," Latham asserts. "It was quite hard to get nice, close sounds, and I remember the bottom end being a bit of a problem, too. That ceiling wasn't my idea, but we used screens, and there was also a drum bay in the far-right corner that could be lowered like a drawbridge if you wanted to deaden the drum sound, so I suppose a bit of thought had gone into the place. For 'Hit Me', we left the drawbridge up and just placed small screens around the front of Charley's kit.

The live room at The Workhouse. You can see Laurie Latham and the side-on API console through the control-room window."There was spill kicking around everywhere, but I just had to get on with it, because by that time the whole notion of trying to be a producer had gone. It was a case of just trying to get it down on tape. With live recordings, what you're looking for is that elusive vibe. It's not necessarily a technically perfect performance but it has something magical about it, and Ian understood that. Quite often we would do take after take after take. I know with 'What a Waste' we did loads and loads of takes, and I did a lot of 24-track, two-inch editing to piece everything together. As it happens, there weren't any edits on the actual 'Hit Me' multitrack, but normally they would go on and on, and Ian would really push to keep going. In that respect I was with him — that's how I think you do it. You sometimes have to go through a real dip and then come back at the other end before you get that magic take, or come back another day and keep at it.

The live room at The Workhouse. You can see Laurie Latham and the side-on API console through the control-room window."There was spill kicking around everywhere, but I just had to get on with it, because by that time the whole notion of trying to be a producer had gone. It was a case of just trying to get it down on tape. With live recordings, what you're looking for is that elusive vibe. It's not necessarily a technically perfect performance but it has something magical about it, and Ian understood that. Quite often we would do take after take after take. I know with 'What a Waste' we did loads and loads of takes, and I did a lot of 24-track, two-inch editing to piece everything together. As it happens, there weren't any edits on the actual 'Hit Me' multitrack, but normally they would go on and on, and Ian would really push to keep going. In that respect I was with him — that's how I think you do it. You sometimes have to go through a real dip and then come back at the other end before you get that magic take, or come back another day and keep at it.

"It's hard work making records, and I think Ian understood that to make a great one you've got to cover all options. He was into spending ages on stuff, and quite happy to sit there listening to a hi-hat part for hours on end, analysing it: 'Is that right or should we try this?' He loved all that. I just wish we could have broken things down just a little bit more rather than have everyone pile in there. I like to deconstruct things, and so it would have been good to continue the way we'd worked on New Boots, getting things down with Chaz, Norman and Charley, as well as Ian doing a guide, and then have the others do overdubs. It's definitely important with a band like that to start off live, but also try to clean things up a bit. After all, the studio wasn't really laid out — there weren't any booths in which I could put the Leslie or the piano, so the whole thing was chaotic.

"Were you to bring up the 'Hit Me' Hammond track it's probably covered in drums. That may be why we overdubbed a very loose-sounding snare fill all the way through. If you listen closely you can also hear the real one ghosting underneath. That was a case of needing a fatter-sounding snare and Charley then trying to track with the original. The overdubbed snare is louder, with the original tucked underneath, and Charley did great. We also ran a DI'd Roland beat box, one of the early drum machines, so there was a load of information going at the same time. We'd just take one output from that little beat box with its Latin rhythms, and that meant Charley and Norman were playing to a click. They were pretty good at keeping time, so we dropped in and out, getting it right, and then the other thing we messed around with was Johnny Turnbull's mad guitar synth, which you can hear throughout.

"The parts were quite well worked out and defined, based around Chaz's piano riff. They all weaved in and out of that, with Johnny playing that quite clean rhythm guitar part, and then Davey's sax solo was, of course, overdubbed. At one point he played two at once — that's his sort of Roland Kirk party piece, and it was at Ian's suggestion. He also used to do it live. Knowing Davey, that probably only took him one take, standing out in the middle of the room with an [Neumann U] 87 on figure-of-eight. Still, there's a very odd moment in the mix — Chris Difford [of Squeeze] is a massive Ian Dury fan, and I always remember him asking me, 'What's that hole at the end of the sax solo?' The part he was referring to is a really quiet piano that chinks away while the bass starts creeping back up, but if you listen to it on certain systems, such as in the car, the piano's so quiet that all you can hear is a gap.

Free For All

"I was never happy with the mix anyway. My authority had diminished and it was a complete free-for-all, with the whole band in there while Chaz basically took over and pushed faders around. I was still doing more of that myself, because with a lot of information down on the 24-track and no computerisation, the two of us did the mix in one pass, like a joint performance. I don't think there were any edits — you know, mixing up to the first chorus, then taking care of the chorus and so on, doing everything in stages. I think it was all done in one go, and in that kind of situation it always helps to keep the tapes nice and clean, erasing anything that shouldn't be there to ensure there's no superfluous stuff. With the advent of computer mixing you sometimes leave the odd thing on there and just mute it, but back then we had to be pretty careful about that.

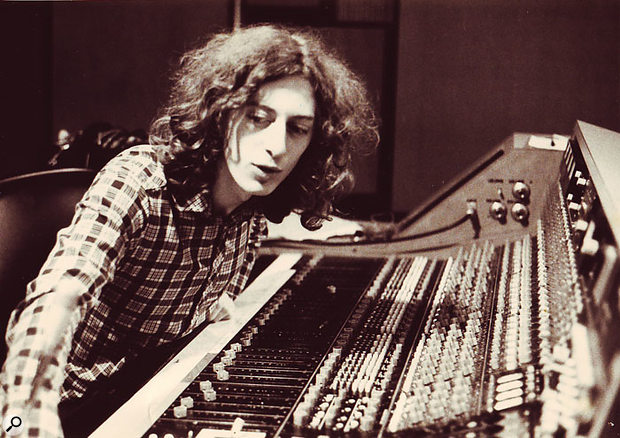

Laurie Latham at "the best API board I've ever worked on", in the Workhouse control room.

Laurie Latham at "the best API board I've ever worked on", in the Workhouse control room.

"Chaz was pretty good to work with, and normally there'd be a consensus between the two of us. I'm sure there were a few alternate takes of 'Hit Me' and that we took them home, had a listen on some dodgy old cassette player that changed the sound, and then came to a decision. Ian didn't say too much during the mixing sessions. He'd ask the odd question, but he had a lot of faith in Chaz. I myself wasn't entirely happy because I didn't think we could hear enough bass, but then I'm never happy with mixes. And while I thought the bass should have been a bit more of a feature — that for a funk part it was a little subliminal — people always pick up on it. They always talk about the bass on that track. To me it was a bit airy and could have sounded a little punchier, but I have to say that it leaps out when you hear it on the radio, so it's got something about it.

"The piano sound was another thing I was unhappy with. Because we did it live, I didn't have enough compressors — God knows why we didn't hire more equipment. On a track like that the piano needs a bit of compression and dynamically some sorting out. Well, to me it sounds like it's getting lost in certain places where it shouldn't, such as the part that Chris Difford referred to. The piano sort of disappears at that point. It gets very roomy and ambient. Still, in the end I suppose all these blemishes give the track a certain character, and if people do talk about the bass then that suggests they can hear it."

For all his reservations about the track, Laurie Latham took the unprecedented step of predicting it would be a chart-topper, as did Chaz Jankel in a phone call to his mum, while Ian Dury asserted the lyrical snatches of French and German should help sales in the Common Market. As it turned out, during an era when so-called New Wave was duking it out with disco, 'Hit Me With Your Rhythm Stick' enjoyed heavy radio play but was initially held at bay in the British charts by The Village People's 'YMCA', which occupied pole position for three weeks before giving way to Dury & Co. Stiff Records had achieved its first Number One, and 'Hit Me', although not a hit in the States, went on to sell just under a million copies in the UK.

Dury Vocals

With The Workhouse's API console positioned side-on to the live area, Latham looked through a window to his right, and for the 'Hit Me' sessions he saw Chaz Jankel to the near-left, playing a Bechstein grand piano, lid down, covered in blankets "and all other sorts of rubbish"; Mickey Gallagher at a Hammond organ, farther along the left wall, with the Leslie cabinet perched atop the aforementioned lift that was used for transporting equipment at the back of the studio; Charley Charles behind his kit in the far-right corner; Norman Watt-Roy playing bass along the middle of the right wall; Johnny Turnbull on guitar at near-right; and Ian Dury with a hand-held mic, sitting on a stool in the center of the room.

"There wasn't a massive selection of mics at The Workhouse," Latham remarks. "I was always frustrated about that. I know there was a mono setup on the Leslie — probably a dynamic mic of some sort on the top, as well as another on the bottom, but that would have gone to mono. A valve [Neumann] U47 was used on the grand piano's bottom strings, with an 87 on the top, and then there was Johnny Turnbull's Roland guitar synth, which was the big new thing at that time. That synth was DI'd, and so was Norman's bass, along with a mic on his cabinet.

"The 47 was a really nice mic, and we'd normally use it on Ian, although not for the guide vocal. Again, we'd use a dynamic mic for that, although I don't think any of the guide vocals made it onto 'Hit Me'. Ian loved being in the studio really, and he loved working on his vocals — he liked spending ages and ages perfecting bits and getting that Dury timbre going. He wasn't one of those people who wanted to make sure the live vocal was captured. He'd already made his mind up that he was going to spend hours and hours doing it all again. In those days a comp would have meant something like three or four tracks, and Ian would like to get one by dropping in. There were lots of drop-ins, with him going over certain lines."

That having been said, getting everything to fit could be interesting, not least because of the way Dury liked to pause or draw words out — "Hit me! Hit me! Hit... mheee!"

"On that song there's one line where it sounds to me like he's actually forgotten the lyric," says Latham, referring to the hesitation, intentional or not, on "From Bom-bay..." "He might have been looking at the words at that point! Still, I don't think his vocal for 'Hit Me' took as long as some of the others, such as 'What a Waste'. I recall it coming together reasonably quickly."

Falling To Pieces

Do It Yourself, Dury's second album (and the first to be credited to Ian Dury & The Blockheads, "Made" according to the sleevenotes "on a new headblock at The Workhouse, under the musical direction of Chaz Jankel"), was released in May 1979 and, like its predecessor, went platinum, selling around 300,000 copies. The sessions, however, were fraught with tension, even though the group-collective style of recording had ironically been replaced by a piecemeal approach centered around a drum machine that presented Latham with a whole new set of problems:

"Ian would sit there, listening to the snare, and go, ''ang on, that one was out with the click! Let's drop that one in.' There was a sort of click paranoia, and it was the complete opposite of what had taken place before. Things definitely went from one extreme to the other. They were all big fans of George Clinton, Sly Stone and that whole funk thing, and I suppose their new obsession with recording everything individually to get perfect separation and get it tight was really just where they were at."

Pub-rock disco would be one way of describing Do It Yourself, but if the engineer was feeling twitchy it certainly wasn't due to dance fever.

"By then it wasn't much fun, to be honest," says Latham, whose subsequent credits would include the Stranglers, Squeeze, Paul Young, Echo & The Bunnymen, Robert Plant, Peter Gabriel and Jools Holland, at whose Helicon Mountain studio he is now based, recently producing a band called the Rays with his son George Latham on drums. "Ian had always been pretty tough to work with, and it got worse as he became successful. I don't think fame and Ian worked very well together, and I only just got through that second album. It had nothing to do with drink or drugs. He did enjoy a spliff, but he was also very anti things like cocaine which, he'd always say, would turn you into a fascist. No, he was just very cantankerous, and sometimes 'Spider' Fred Rowe, his minder, would even take the calliper off his leg so he could dump him on the couch to stop his destructive ranting. The whole thing was ugly.

"As I've said, after 'Hit Me' everyone was chipping in, and when it came to Do It Yourself this included the bloody road crew as well! Some of them were sitting behind the mixing desk, so I was gradually fading away, physically and mentally, and I definitely thought, 'I've had enough of this'. At that point, Ian had got rid of Peter — I don't know why, but obviously a few things had gone down and he was banned from the studio. And then, halfway through the sessions, Ian himself was banned. I don't think he had enough material for that album, and so he was panicking a bit and making things up as he went along. He appeared to be insecure in the studio and he was really disruptive, and it ended with Chaz calling him and saying, 'You'd better not come down any more or we're never going to get this record done'. It was so unpleasant, I myself was thinking about doing something else, like joining the Post Office or becoming a milkman.

Laurie Latham today with his latest production project, the Rays.

Laurie Latham today with his latest production project, the Rays.

Broken Biscuits

"Still, we got through it, and about 18 years later I got back together with Ian. He'd asked me a couple of times and I'd thought, 'No way am I ever going through that again,' but I ended up mixing Mr Love Pants, which was a great album, at AIR Studios. Then, when we worked together on his last album [Ten More Turnips from the Tip], I did remind him about some of his moments in the early days. I reminded him of the moment during Do It Yourself when he went through everybody in the building and gave them all a new job, telling them what they should be doing. I forget what he told me I should do, but he then ended the whole thing by standing behind me, crushing an entire packet of McVities digestive biscuits, and throwing them all over me and the desk. The faders, the EQ — the entire thing was smothered, and it took me weeks to clean.

"I don't recall what it was all about. He was just in a rage, shouting at everybody, and then the biscuits went everywhere — including my hair — and he left, and I didn't see him for several weeks. That's probably when Chaz phoned him and told him to stay away. Anyway, years later, when we were working at RAK Studios on yet another API, I reminded Ian about that incident. He was quite ill at that point, and he was holding his stomach, laughing his head off. It really cheered him up. The fact is, I really did love Ian, but I didn't always want to be around him. He wasn't the kind of guy to invite to your party, because within five minutes it would be Ian's party, and if it wasn't Ian's party he would make sure to disrupt it.

"That's why I was so pleased when we reunited for Mr Love Pants and then did the final album, which was actually finished off here at Jools' place. We got quite close again, and even when he was cantankerous it was in a much more jovial, jolly way. You'd think he'd been dealt as many dodgy cards as you could get in life, but he battled on to the very end, and we did have a few laughs. I'm really grateful for that.'