The live room at Scepter Studios. Norman Dolph said this was "shot through the glass, standing at a position midway between the mixing desk and the producer's desk — ie. if the young man in the control room stood up and took a shot, the studio picture would be the result.”

The live room at Scepter Studios. Norman Dolph said this was "shot through the glass, standing at a position midway between the mixing desk and the producer's desk — ie. if the young man in the control room stood up and took a shot, the studio picture would be the result.”

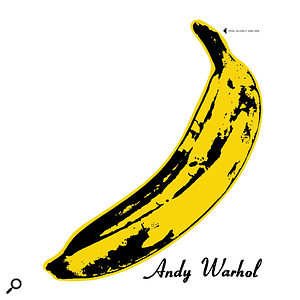

Its status as one of pop's most influential albums is clear, but the circumstances surrounding the creation of The Velvet Underground & Nico have always been clouded. We asked Andy Warhol's co-producer to set the record straight.

"The advantage of having Andy Warhol as a producer was that, because he was Andy Warhol, they left everything in its pure state,” Lou Reed told a TV interviewer in 1993. "They would say, 'Is that OK, Mr Warhol?' and he'd say, 'Ohhh, yeah,' and so they didn't change anything. And so right at the very beginning we experienced what it was like to be in the studio and record things our way and have, essentially, total freedom. The record company never listened to the records in the first place, so they came out exactly like they'd been made and we got to experience that freedom. But the only real reason I think we had that freedom is because Andy as the 'producer' was saying, 'Ohhh, that's great.'”

Like pop-art pioneer Warhol's excursions into the world of film, his involvement in the mid-'60s music scene via the Velvet Underground had limited commercial appeal but was highly influential. It was as the manager of the New York-based group co-founded by singer-songwriter-guitarist Reed and Welsh bassist-violist John Cale — with Sterling Morrison playing guitar and bass alongside Maureen 'Mo' Tucker on drums — that Warhol ensured he was credited as the producer of their seminal debut album The Velvet Underground & Nico, featuring the contributions of the German-born singer who was another of his protegés. Nevertheless, despite showcasing the VU in his multimedia Exploding Plastic Inevitable music/film/dance/lighting events, Andy Warhol barely participated in the avant garde outfit's 1966 recording sessions for an LP steeped in Reed's lyrical references to sex, drugs, depravity and the denizens of Warhol's Factory art facility. Instead, these were handled by Columbia sales exec Norman Dolph and Scepter Records engineer John Licata before three of the songs were then re-recorded, others were remixed and another added by Verve staff producer Tom Wilson and engineer Ami Hadani.

The Velvet Underground and Nico and Andy Warhol. From left to right: Nico, Andy Warhol, Moe Tucker, Lou Reed, Sterling Morrison and John Cale.Photo: Steve Schapiro/Corbis

The Velvet Underground and Nico and Andy Warhol. From left to right: Nico, Andy Warhol, Moe Tucker, Lou Reed, Sterling Morrison and John Cale.Photo: Steve Schapiro/Corbis

"Of course, he didn't know anything about record production, but he didn't have to,” Lou Reed remarked when discussing Warhol's studio activities in an April 1989 Musician Magazine feature by Bill Flanagan. "He just sat there and said, 'Oooh, that's fantastic,' and the engineer would say, 'Oh yeah! Right! It is fantastic, isn't it?'”

Norman Dolph concurs with Reed's recollection. "Warhol was in the control room for part of two of the four days John Licata and I worked on that record,” he says. "He was never there for any eight-hour stretch: more like 30 minutes, during which he'd stand behind me, listen to a playback and say, 'Oh, yeah, yeah, that sounds great.' I don't think Warhol gave us the slightest instruction or command, and nobody really asked him what he thought of the recordings. Usually, there'd need to be a consensus between John Cale and Lou Reed; if they agreed on something, it was 'next track'. And if they didn't, Cale normally won, although Reed had the final say over his own singing. Everyone deferred to him on 'Heroin' and 'Waiting For The Man'.

"Warhol always carried a small recorder with him — he preserved a cassette version of every breath he drew — and as soon as anyone said anything he would record them. He let things happen around him and then commented on or utilised those events and images for his works of art. He considered his life to be a manifestation of that. So, somewhere in the Warhol archives in Pittsburgh there are probably cassettes from Andy's visits to the sessions.”

Exploding Plastic Inevitable

It was in 1960 that Norman Dolph joined Columbia Records' Custom Manufacturing division in Chicago upon his graduation from Yale University, where he majored in electrical engineering. At that time, a lot of major record pressing plants produced discs for independent labels, and so Dolph quickly found himself handling Columbia's custom-pressing business for Motown, Vee-Jay and Chess before returning to New York in 1962 and dealing with the likes of Roulette and Colpix. In the course of this work, liaising between Columbia and the independent labels, Dolph amassed an impressive collection of free sample records — which has grown into a collection of more than 28,000 vinyl discs — and utilised them as a mobile DJ. This sideline not only proved to be financially beneficial, but it also resulted in some unexpected perks.

"I was one of the first mobile DJs in America,” he says. "I'd do parties all over New York and the environs, and having been an art collector since college, I began providing the music for artists and galleries in celebration of openings. Instead of taking cash, I'd take a piece of art in exchange for the fee, and in the long haul that turned out to be a very prudent decision. One of the artists that I wound up getting involved with was Warhol. I did four events for him, including his first museum show at the Philadelphia Institute of Contemporary Art in 1965, and in each case I did so in exchange for some artwork.”

The floor of 254 West 54th Street in New York that once housed Scepter Studios. Its lease is up, if anyone's interested in starting a studio or a nightclub...

The floor of 254 West 54th Street in New York that once housed Scepter Studios. Its lease is up, if anyone's interested in starting a studio or a nightclub...

In March and early April of the following year, at The Dom on St. Mark's Place between 2nd and 3rd Avenues, Norman Dolph DJ'ed at two Exploding Plastic Inevitable parties that featured Andy Warhol's films, as well as his Factoryites dancing to live performances by the Velvet Underground and Nico.

"Warhol said he needed me to spell them in between sets, so I played my black soul music,” Dolph recalls. "My ear as a record collector developed in line with my eye as an art collector, and in both cases my reaction to something new would be instant, be it positive or negative. With some stuff I'd immediately think, 'Whatever this is meant to be, it isn't art,' and I must confess I had a little of that reaction when I first saw and heard the Velvet Underground. There was no yardstick to accurately measure what they were doing, especially within the context of contemporary music. For sure, I wasn't smoking or ingesting the things that affected a lot of people's reactions during that psychedelic era, and I can't accurately recall my reaction when I first saw the Velvets perform, but I did know we were dealing with something unprecedented.

"Don't forget, I wasn't sitting in the audience and seeing them from the audience's perspective. I was in the wings, on the periphery of their on-stage performance while [poet/photographer/filmmaker/music choreographer] Gerard Malanga did his whip dance and one of the roadies walked around with a 16mm Bell & Howell projector on a long extension cord, projecting Warhol's movies on the wall and on various artists. Rudi Stern's wall-to-wall psychedelic light show was brand new to New York City, the whole experience was what we'd now perceive as a YouTube video, and I'm sure people's initial reaction to the group — including my own — had as much to do with what was going on visually as with what was going on in terms of the music.

"When Warhol told me he wanted to make a record with those guys, I said, 'Oh, I can take care of that, no problem. I'll do it in exchange for a picture.' I could have said I'd do it in exchange for some kind of finder's fee, but I asked for some artwork, he was agreeable to that, and I think I made a wise choice. In my experience, I never saw him disagree with anybody about anything. He might laugh or be a little bit dismissive, but I never heard him say he thought something was stupid. In this case, he said, 'OK, go ahead and do it,' and that's what led to me working with the Velvet Underground.”

Scepter Studios

A plan showing the layout of the studio within the office building.

A plan showing the layout of the studio within the office building.

"The guy who deserves a lot of the credit for that first record is John Licata: the nicest guy you'd ever want to meet and extremely co-operative. He had a deal with Scepter and was a journeyman engineer who might record a gospel choir in the morning, Dionne Warwick in the afternoon and some doo-wop group later in the day. He was capable of doing anything and he'd worked out a perk with the studio: if the studio wasn't booked, he could book time there with outside clients, do the engineering and pocket the money. When I approached him to record the Velvet Underground album, he told me the sessions would cost a total of between $600 and $800.

"Scepter was one of the very successful independent labels I worked with — it had artists like the Shirelles and Dionne Warwick as well as its own studio. The company occupied one floor of a typical New York office building; most of it comprised offices staffed by about 20 people, while the studio took up the equivalent of about 12 cubicles and the control room was the size of about three cubicles. Maybe two people could sit and two others could stand at the same time in that control room, and although it had windows, they had been covered over with acoustic material. Then again, the studio — which wasn't particularly big — had a window that looked out to the hallway, so people going back and forth to the coffee machine were able to look in and see what was going on.”

Norman Dolph recalls the control room housing a 24-input console and four-track Ampex half-inch machine, and there's a general consensus that Scepter Studios was in a fairly run-down condition at the time of the Velvet Underground & Nico sessions. Holes in the floor and badly damaged walls would prompt John Cale to describe the place as "post-apocalyptic”, yet the music that he and his colleagues recorded there has become the stuff of legend.

"Jerry Wexler was once asked what he did when he produced Ray Charles,” Dolph continues, "and he said something along the lines of 'I turned the lights on in the studio.' I know what he meant. I put up the money for the Velvet Underground sessions and, because of that, I was very interested in keeping things on the rails. For their part, the band members wanted to capture a very spontaneous sound, rather than do loads of takes and overdubs, and I was quite happy with that faster way of working. The group was red-hot at that time, performing five nights a week, so nobody wanted to mess around when it came to getting a record out. The whole thing was therefore produced over the span of four days; two fairly long ones recording and then two fairly short ones mixing.”

It was a week or two after first seeing the Velvet Underground perform as part of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable that Dolph found himself producing them at Scepter.

"I had far more of a reaction to them in the studio than I'd had when seeing them on-stage,” he says. "'Appeal' wouldn't be the right word to describe their music's effect on me. I was impressed by it as an achievement, and I had a strong sense that I was in the middle of something very singular and unusual, but neither John Licata or I realised we were witnessing the birth of something historic.

"While Licata had his hands on the console's rotary knobs, I had my hand on the talkback and John Cale kept the ship afloat. He and Lou Reed both did, but whereas Lou contributed his musical talent, John Cale's was the voice of coherence — notwithstanding the fact that he referred to me in some interview as a 'shoe salesman', I kept him on course to get the sound he wanted.

"There was a lot of ego going on, and I was fortunate to have John Licata there, handling it as smoothly as anyone you can imagine. While they'd be setting up, playing a few licks and deciding exactly what they were going to do, he would balance the sound and, after they'd hear the playback, John Cale would say, 'Yeah, that sounds great.' Cale and Reed told Licata they wanted to sound the way they did when they performed live, and he achieved that on the first pass of every song without ever having seen their live performance — and without getting any credit in the liner notes of the released record.”

Songs Of Experience

"Looking through the control room window, I could see Maureen in the centre, with her back to the far wall, and I don't remember there being any baffles around her. She had a very small kit and it did not make a lot of noise. When Lou sang, his back was to her and his microphone was centred in the room, not far from the control-room glass. Sterling was a little closer to Maureen, standing in the far right corner with his back toward the wall, and John Cale was on the left side with his viola, in profile to the control room, facing Lou.

"Cale looked like Paganini possessed by the devil when he played that viola; it was as if he might saw it in two with the bow. Seeing him perform his rhythm patterns was very memorable to me. I wasn't at all accustomed to seeing power like that coming out of a bowed-string instrument.”

A copy of the cheque Andy Warhol gave Dolph to pay for the pressing of the Columbia acetate.

A copy of the cheque Andy Warhol gave Dolph to pay for the pressing of the Columbia acetate. In Cale's case, said instrument had guitar and mandolin strings on which he achieved a droning sound by playing sustained single notes while mixing things up by varying the speed and the attack as well as adding other notes to vary the tone. 'Venus In Furs' and 'Heroin' feature prime examples of this experimental approach, the latter redolent with wailing and screeching during the passages when the song accelerates in tandem with the drug-related rush experienced by the narrator.

"I think 'Heroin' was the last song we recorded, and it came as a complete surprise to me because, unlike most of the other material, I hadn't seen the group perform it live,” Norman Dolph recalls. "When Cale overdubbed his part, we were all holding our breath, hoping the dynamics would work out right and that it would be done in one pass. No way would I even pick up a pencil and move it an inch while that was going on. As it turned out, there may well have been two complete takes — any iffyness about the first one would have prompted him to say, 'OK, let's do another' — but there certainly wouldn't have been three.”

Cale himself likened the sound he made on the viola, when played loudly, to that of an aeroplane engine, and Dolph agrees: "Victor Hugo once told his fellow French poet Charles Baudelaire that, with his art, 'you create a new shudder', and that's how I felt about John Cale's viola. He had to know what was going on harmonically and musically in order to make that sound.

"Ordinarily, I would have preferred to hear Otis Redding, but Cale's playing impacted me in the same way that I'd sometimes get from a painting. Also, I remember that, when I was listening to Lou Reed record his vocal for 'Heroin', I thought, 'My God, this guy has first-hand experience, he's not just making it up. He knows what he's talking about.' It was almost scary in that sense — you know, this is real, this is not a song any more.

"That said, after 'Heroin' had been recorded, I did ask myself the business/economic question about who was going to pay several dollars for a vinyl record that contained this song about drug addiction. I mean, whereas you might enjoy the Rolling Stones' 'Satisfaction', you'd experience 'Heroin'.”

Equally experimental was Lou Reed's 'ostrich' guitar tuning on 'Venus In Furs' and 'All Tomorrow's Parties'. So named because he had first used this technique for the 1964 dance number 'The Ostrich' that he and John Cale recorded as members of a group called the Primitives, it consisted of Reed tuning every string to the same note to produce a drone that mirrored Cale's on the viola.

"It's a powerful sound. I didn't realise that's how he achieved it,” Dolph admits.

Here She Comes Now

With the VU mainly playing live together as a band, overdubs were kept to a minimum, including those for Nico's vocals on 'Femme Fatale', 'All Tomorrow's Parties' and 'I'll Be Your Mirror'.

"I don't remember doing any punching in,” Dolph says. "Everything was done from the top and there was certainly no 'Let's tune up measure 71.' Most of the songs were done in one take and, at the most, a song would be compiled from two half-takes.”

Dolph also confirms that, although John Cale and Lou Reed only agreed to Nico's involvement because Andy Warhol insisted on it, they didn't make this obvious to her in the studio.

"When she sang it was kind of surreal, like you were in a place that was new and different, and everybody was highly respectful of her need to be given space to perform in front of a microphone,” he says. "She had a very fragile personality, everyone shut up as soon as she was about to record a vocal, and afterwards she would lean up against a wall somewhere, as if she wasn't in the room. I'm not sure anyone ever asked her what she thought of a playback, and I also don't think they did all of her songs in one sitting. They'd do some of their songs and then some of hers as a way to relax from the more high-energy ones.

"At that time, raw tape cost about $150 per reel, and so the concern was the time and the materials, especially when a song got off to a tentative start. I'd break it down and tell them, 'I don't think you'll be happy with this.' They'd agree and so we'd rewind and redo it. On the other hand, if they made it all the way through a take, they'd come into the control room and listen to it before deciding if it should be kept or redone. Sometimes, the band members would listen to a playback in the studio, where there was more room, but when they wanted to listen to something closely and get the same ear load that Licata was getting, we'd leave the door open so two of them could walk in and the other two could scrunch in and listen over the control-room speakers.

"I never heard any fracas or argument between the band members. Cale was musical in truly the 'art' sense and he had a full understanding of the music they were making. For his part, Sterling was generally very quiet, but every time he made a comment it seemed to be right on the mark, and Maureen rarely came into the control room or made a comment that was loud enough for me to hear. She played the drums and was clearly engaged in what was going on, but she was even quieter than Sterling. Nico was the same. In fact, when Nico did speak, she whispered — she spoke much like she sang.

"Sometimes only Licata and The picture — one of the Silver Disaster series — that Dolph received in payment for his work with the Velvet Underground. I would engage in production comments. He would ask me, 'What do you think?' and I might say, 'Sounds fine to me.' Or I would ask him 'What do you think?' and he'd say, 'I'm still playing with it, give me a minute.' John Licata was focused on making the band members happy, and they were very comfortable with him from the time they walked in the door. Had that not been the case, it might have been a totally different record. Them being happy with him, and me only wanting to keep it going, keep it going, keep it going, is what made the record sound the way it does.”

The picture — one of the Silver Disaster series — that Dolph received in payment for his work with the Velvet Underground. I would engage in production comments. He would ask me, 'What do you think?' and I might say, 'Sounds fine to me.' Or I would ask him 'What do you think?' and he'd say, 'I'm still playing with it, give me a minute.' John Licata was focused on making the band members happy, and they were very comfortable with him from the time they walked in the door. Had that not been the case, it might have been a totally different record. Them being happy with him, and me only wanting to keep it going, keep it going, keep it going, is what made the record sound the way it does.”

The Verve Connection

On 25th April, 1966, an acetate was cut with a view to obtaining a record deal. Excluding the recording of 'There She Goes Again' that would end up on the released album, this contained nine of the 10 tracks recorded at Scepter: 'I'm Waiting For The Man', 'Femme Fatale', 'Venus In Furs' (based upon the sado-masochistic 19th Century novel of the same name), 'Run Run Run', 'All Tomorrow's Parties' (Warhol's favourite song on the album, describing some of the people who frequented his Factory), 'Heroin', 'I'll Be Your Mirror' (a Reed and Dolph favourite, inspired by Nico), 'The Black Angel's Death Song' and 'European Son', dedicated to poet Delmore Schwartz.

"They wanted to make an acetate for Columbia Records on the presumption that, this group was so hot and it's connection to Andy Warhol offered so much built-in PR, the company would snap it up in five seconds,” Norman Dolph explains. "Columbia cut masters and reference acetates for outside clients. So, Warhol wrote Columbia Records a cheque for $84, handed it to me, and I gave it to Columbia along with the quarter-inch mixed master tape. Today, if you sent Columbia a tape filled with three minutes of John Cage's silence, they'd probably put it out, but back then I got an inter-office memo within 24 hours, basically stating I must be out of my mind. Columbia passed on it so fast, my head spun.

"At that point, I gave the acetate back to Warhol and told him I was sorry while expressing how surprised I felt that Columbia had passed. Warhol said, 'Well, come by and pick up your painting, and we'll see what happens.' I don't know what his next move was, but the album was shopped to several other labels that rejected it before it was picked up by Tom Wilson at MGM/Verve.

"Columbia had a meeting every week at which all of the A&R people — from country to classical — would belly up to the bar and say, 'This is the new product I've been working on. What do you think? Should we sign this artist?' It must have been thumbs down all around the table when they heard the Velvet Underground acetate. Tom, a wonderful guy, was my colleague at Columbia at that time, and logically he would have been at the A&R meeting. So, it wouldn't surprise me if he thought, 'I should keep an eye on this,' and went after the record when, a short time later, he left Columbia and resurfaced at Verve. I cannot say that's a fact, but it's absolutely a possibility.”

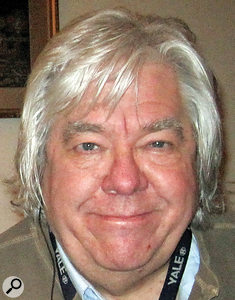

Norman Dolph today.

Norman Dolph today.Over the course of two days at Hollywood's TTG Studios in May 1966, Tom Wilson and engineer Ami Hadani (credited as Omi Haden) presided over the Velvet Underground's re-recordings of 'Heroin', 'Venus In Furs' and 'Waiting For The Man', all three at a slower pace and with slightly amended lyrics. Lou Reed now commenced singing 'Heroin', the album's second longest track, with "I don't know just where I'm going,” instead of "I know just where I'm going,” and his guitar line was different, while Mo Tucker's slightly more sophisticated drumming stopped for a few seconds at around the 6:20 mark.

"As soon as it got loud and fast, I couldn't hear anything,” she explained in the 2006 documentary The VelvetUndergound: Under Review. "I couldn't hear anybody, so I stopped, assuming, well, they'll stop too and say, 'What's the matter, Mo?' But nobody stopped... so I came back in.”

Meanwhile, the Scepter recordings of 'Femme Fatale', 'Run Run Run', 'All Tomorrow's Parties', 'I'll Be Your Mirror' and 'The Black Angel's Death Song' were remixed, and in November of that same year, when Verve required a more commercial track to release as a single, Wilson took the band into New York's Mayfair Studios to cut 'Sunday Morning' with Nico singing the lead vocal. (As it turned out, she ended up backing Lou Reed.)

All Tomorrow's Parties

When The Velvet Underground & Nico was released on 12th March 1967, it featured a much shorter, less bluesy take of 'European Son' from the Scepter sessions as its closing track. Still, while the album's unconventional music hardly suited the playlists of most radio stations, its controversial lyrical content ensured they and numerous record stores also banned it. Verve's promotion and distribution were lacklustre at best, many magazines refused to review or advertise the record, and as a result it peaked at just 171 on the Billboard 200 chart.

It took a full decade and a change in cultural attitudes for the album — easily distinguishable courtesy of Andy Warhol's iconic front-cover banana artwork — to be critically reappraised and have its artistic impact properly acknowledged. In 2006, it was added to the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress and is now widely regarded as a solid-gold classic, none of which Norman Dolph could have possibly conceived at the time of its Columbia rejection or Verve release.

"I just enjoyed lookingat the painting that I'd received as payment and thought it was a fair trade for delivering the album under budget,” says Dolph who, as a songwriter, penned the 1974 Reunion hit 'Life Is A Rock (But The Radio Rolled Me)' and has since become a software developer. "Later on, Rolling Stone named it as number 13 among the '500 Greatest Albums Of All Time', and it still surprises me to have been part of something that has had such a worldwide influence on people. What was there back then I helped put in the grooves, but I didn't hear then what I hear in it now, and to be honest I still doubt the premise that a drug-sensitised mind would want to hear — and could enjoy — a song about heroin... Even though, for me, it was a high-water mark to be across the glass from that.”

The Lost Acetate

The Velvet Underground & Nico acetate that Norman Dolph handed back to Andy Warhol after it was rejected by Columbia Records eventually went missing, and it only turned up in 2002 after a Canadian collector named Warren Hill bought it at a flea market in the Chelsea district of New York City... for 75 cents.

"One dinnertime, I got a call out of nowhere from Mr Hill, asking if I'm Norman Dolph and if I had anything to do with the Velvet Underground. When I said yes to both, he told me about having bought the acetate at the flea market, and I think he wanted to get it on record that I wasn't alleging it had been stolen from me. He then dictated to me a number that was printed on the acetate [XTV-122402] and, hearing the prefix, I was able to confirm that it was a bona fide Columbia Records library number.

"After we ended the call, I contacted a guy in the Columbia library and read him the number so he could find out the location of the master tape. The next day, he called back and told me that, every five years or so, a truckload of stuff is packed up and sent to Iron Mountain [data storage facility] for safekeeping. This tape was so old, that's where it must be, and although the index card would indicate if the tape had since been returned to its rightful owner — as is usually the case with non-Columbia-owned property — in this case the card was so old that it, too, had been shipped to Iron Mountain.

"So, somewhere in Iron Mountain is the quarter-inch mix of the acetate. The first purpose of that mix was to make something good enough to entice Columbia to sign the group, and it was, therefore, probably a little less formal than it would have been if intended for a vinyl record. I never had my hands on the half-inch master after it was fully done. John Licata had been paid the money, it had been mixed to everybody's satisfaction on quarter-inch, I took that to Columbia to cut the acetate, and the half-inch ended up with Warhol or, more likely, his associate Paul Morrissey, the film director who discovered and signed the Velvet Underground.”

of that mix was to make something good enough to entice Columbia to sign the group, and it was, therefore, probably a little less formal than it would have been if intended for a vinyl record. I never had my hands on the half-inch master after it was fully done. John Licata had been paid the money, it had been mixed to everybody's satisfaction on quarter-inch, I took that to Columbia to cut the acetate, and the half-inch ended up with Warhol or, more likely, his associate Paul Morrissey, the film director who discovered and signed the Velvet Underground.”

As for the hallowed acetate, Warren Hill eventually auctioned his find on eBay, and he had to do so again when a winning a bid of $155,401 wasn't honoured. On 16th December, 2006, it sold for $25,000, and in 2012 it was at last released to the public as part of the album's '45th Anniversary Super Deluxe Edition' box set that also included a half-dozen previously unreleased tracks from the band's 3rd January 1966 rehearsal at The Factory.