On his second solo album, Van Morrison took the production reins for the first time. Manning the desk was engineer Shelly Yakus, who tells the story of recording Moondance.

George Ivan Morrison. Van The Man. The Belfast Cowboy... Regardless of the name or the identity, Van Morrison is hard to categorise. A vocalist whose idiosyncratic growl characterises an unusual, highly influential style that, according to critic Greil Marcus, "no white man sings like,” as well as an award‑winning multi‑instrumentalist, songwriter, poet and author, Morrison has pursued an eclectic musical path since first rising to prominence as a member of the Northern Irish band Them in the mid‑'60s.

While R&B and American soul have clearly informed much of his work, including such early successes as the self‑penned garage rock classic 'Gloria' (1964) and his first solo release, 'Brown Eyed Girl' (1967), he has also given free rein to his penchant for jazz, blues, gospel, country, Celtic folk, spirituality and lengthy stream‑of‑consciousness narratives. These have been highlighted on songs ranging from 'Moondance' and 'Domino' (both 1970) to 'Bright Side Of The Road' (1979) and 'Have I Told You Lately' (1989), as well as on a series of highly acclaimed albums including Astral Weeks (1968), Moondance (1970), His Band & The Street Choir (1970) and Tupelo Honey (1971) that runs all the way to Magic Time in 2005 and Pay The Devil in 2006.

Amid this rich, detailed tapestry of work, Astral Weeks, with its mixture of folk, jazz, R&B and improvisation, established a standard of excellence that has seen it consistently being voted one of the top albums of all time. While its generally introspective, pessimistic tone perhaps accounted for its lack of commercial success, this was rectified by its equally brilliant yet far more upbeat successor, Moondance, which peaked at number 29 on the Billboard chart following its release in February of 1970. Featuring such timeless gems as 'Caravan', 'Into The Mystic', and the title track that Van Morrison has performed more than any other number in concert, this record saw him enter New York's A&R Recording studio with only the song arrangements in his head and a determination to do things his way.

Two Horns & A Rhythm Section

After 'Executive Producer' Lewis Merenstein populated the first session with many of the musicians who had contributed to Astral Weeks, Morrison "sort of manipulated the situation and got rid of them all,” according to guitarist John Platania, who was part of the band that did end up playing on Moondance. Alongside him were Garry Mallaber on drums, John Klinberg on bass, Jeff Labes on piano, Jack Schroer on alto sax, and Collin Tilton on tenor sax and flute.

"That was the sort of band I dig,” Morrison would later say. "Two horns and a rhythm section — they're the type of bands I like best.” And he also saw fit to produce himself for the first time, commenting, "No one knew what I was looking for except me, so I just did it.”

"Not that he had a whole lot to say during those sessions,” remarks Shelly Yakus, who engineered behind the console in A&R's Studio A. "I remember him telling me to put more bottom on his voice, but those were probably the only words he said to me throughout the entire project! He was very quiet and really introverted, yet when he sang it was a 'Holy Shit!' moment.”

A&R actually comprised a number of different facilities: the original, opened in 1961, was located on the fourth floor above a much‑loved bar named Jim & Andy's at 112 West 48th Street, and this was eventually supplemented and then replaced by another at 322 West 48th Street and one at 799 7th Avenue. The 7th Avenue location had two recording rooms and a mix room, and it was there, in the Studio A penthouse, that most of the sessions for the Moondance album took place in August and September of 1969.

Resisting Change

"Studio A had a custom board with round knobs on it and no EQ strips,” Yakus recalls. "It was very straightforward, with a patchbay, some reverb sends, a bus selector over each knob and a bunch of meters. They had that console for years. Even when other places were getting more sophisticated boards, A&R resisted changing theirs because they knew they had a sound. And even though they eventually had to go to a Neve in that room to keep attracting clients, that board today would still make a great sound.

"The tape machine was a Scully eight‑track, and they used a combination of Ampex and Scully machines to record the other masters and safety copies. The main monitors were Altec 604Es, and we found that running three speakers at the same time in that large control room was accurate. We'd therefore run it in mono. For instance, [the Band's] Music From Big Pink was recorded there on four‑track, and in order to get the balance right we'd listen in mono. We could've split it in stereo, but it was safer to listen in mono and listen as a finished record. Listening in mono with a proper balance, everything ends up combined correctly on the tracks, and from that I learned that, if I listened to everything together rather than just listen to a solo forever, I could work one instrument against another and get everything right. It's not so much what your EQ is doing to one instrument, it's what that sound is causing all of the others to do.

"There was some basic equipment in the Studio A control room, including a Fairchild, Altec limiters, Altec EQs, Pultec EQs and some great‑sounding EMT chambers, which is one of the secrets to making really good records. The room sounded wonderful, too.

"There were other studios that maybe had a more focused sound, a little more aggressive in the middle, and the radio loved that, too. But A&R just had this clarity about it without being thin, and that's very difficult to do. Most people get clarity by thinning stuff out, but in this case it was due to whoever designed the room and created that environment getting it right. It had a very even bottom, middle and top with clarity, without it being foggy or jumbled, and also with punch. The radio doesn't like stuff that's dark and thick, and in those days they used a different kind of compression that would make stuff muddier if you didn't have a clear sound.”

The Deep End

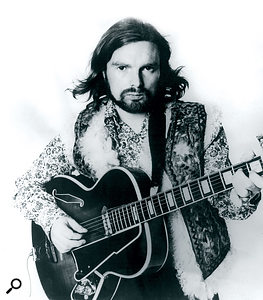

Van Morrison on stage, 1970.Photo: Retna

Van Morrison on stage, 1970.Photo: Retna

At the time of the Moondance project, Shelly Yakus's main studio experience had previously been as an assistant only, and therefore the opportunity to record Van Morrison as a fully‑fledged engineer came as a bolt out of the blue.

"In those days, there were two young women who handled the bookings at A&R,” he says. "It was a very busy studio complex, and they had a book on an easel which they would amend as the calls came in. Those girls controlled an engineer's life, informing clients who was available and best suited to work on a specific project, and one day they called me to say I was being recommended to work with Van Morrison. I said, 'Well, what's the setup?' and they said, 'It's bass, drums, guitar, vocal and horns.' I said, 'I've never recorded horns,' and they said, 'Well, you can work it out.' They had probably checked with some of the engineers I'd assisted and been told that I could do it. I must have done enough, I guess, to capture someone's ear, and so I had to figure out how to record horns on the session.

"I had become pretty good at recording the rhythm section, but doing the horns was a whole new experience, and a not particularly easy one when we overdubbed some of those parts at the studio on 48th Street. The board over there was a Neumann, and it was very hard to record horns because its level structure was unusual. When the horns played quiet, you'd have to open up the preamps quite hard to get the right level. But then, when they went into a passage of the same song that played loud, the board would break up because the preamps couldn't cope. I don't know if that board conformed to a European style of recording, but A&R eventually had to get rid of it because it was too difficult to use for the type of music that we were doing. When I tried to record horns on it, it was never a good day.”

Not that Yakus had any choice when he had to learn on the job how to track the alto and tenor sax for 'Moondance'…

"That's how it was,” he reasons. "You'd be assigned to different sessions all the time, and so it was common for multiple engineers to work on the same project. We were all just trying to make the best music that we could. And the music was so great, it made everything all right. Back then, it was about the song, whereas now it's about taking four bars and making it into a song! ”

Different Voices

Which is why Yakus has no regrets about — and, indeed, had no say in — Steve Friedberg, Tony May, Elliot Scheiner and Neil Schwartz also engineering various parts of the Moondance album. He was just happy with his own involvement, which in the case of the title track amounted to his taking care of the recording and Scheiner handling the mix.

"It was remarkable to hear those songs coming out of the big speakers in the studio,” he says. "I always rode each vocal as if I was mixing the track, doing it live and learning the vocal with the singer. I'd sing it to myself and would actually ride up the beginning or end of words if he was swallowing them. That way, the vocal was as complete as I could possibly get it, regardless of who would be doing the mix, and the engineer could then spend his time getting a cool sound on the vocal and fitting it to the track rather than doing what I did and maybe take a chance on over‑limiting it to get the words up.

"Singers have many different styles, and you have to try to understand what they're doing at any given time. All we're trying to do is make the colours more vivid. In fact, if you listen to the first six numbers on Moondance, Van doesn't use the same voice twice. It's all him, but he's using his voice like it's an instrument and expressing himself on each song to get it across as he envisions it. Listening to those songs one after the other is an amazing experience. Each song is fabulous from beginning to end, and the next one is nothing like the one that came before, yet its melody is just as strong and just as all‑consuming.

"Constantly changing your voice like that runs the risk of sounding affected if you don't get it right, but he got it right. I can't say that he thought, 'Oh, I'm going to use this voice on this song.' I think it just came out that way. I think he'd write the song and base his voice on the content, feel, key and tempo. Listen to those songs and you'll hear that every vocal fits with the melody and with the track.”

Microphones

Shelly Yakus in his home studio today.

Shelly Yakus in his home studio today.

Although the A&R Studio A live area was large, only the right-hand side of it (as seen from the control room) was utilised for Moondance, with the drums surrounded by the rest of the rhythm section. The left side of the room was mostly reserved for string sessions, as well as for risers to record Broadway plays and cast albums. Singing live with the band, Van Morrison was positioned opposite the control room, at the far end, in an uncommonly large booth that could accommodate a lead singer on one side and a vocal group on the other, separated by a glass partition that enabled them to see each other as well as the band.

"I had just one mic on Van, a [Neumann] 67, going through a Pultec and a limiter,” Yakus recalls. "I probably used one side of a Fairchild on him and found the setting that I liked. I never was a guy who used a whole lot of EQ when I was recording. I was just trying to get everybody to fit together and leave some room for later on. The 67 is pretty full‑sounding, and it worked with the bottom end of his voice for all of the tracks, regardless of how he sounded.

"Back then, you had to give the singer a really good track balance, with him maybe a little louder than if it were an actual finished record. That's what Van heard. It was very much like a finished record aside from what he wanted in terms of his own voice, whether it was a little louder or a little quieter, and with one mic that fit his voice he could do anything and still have it sound like him. So long as the mic itself was very frequency‑even and that the equipment hooked up to it was frequency‑even, he could do a lot.”

The miking of Gary Mallaber's drum kit comprised an Altec 633A 'Saltshaker' on the snare, together with Shure SM57s on the kick and on the hi‑hat, a Neumann U87 on each pair of tom‑toms, and U87s as overheads. Meanwhile, with a combination of DI and an Electro‑Voice RE20 used to record John Klingberg's bass, an SM57 and Beyer 160 were used for John Platania's guitar. A Sennheiser 421 took care of the low end and a U67 the high end for the piano played by Jeff Labes, while a U67 covered Jack Schroer on alto sax and a Sony C38 FET was used for Collin Tilton's tenor sax, as well as a U67 for his flute overdubs.

What Was In Van's Head?

"Although Van didn't come to the studio with music charts, he and the band must have rehearsed the material before we started recording,” Yakus surmises. "I mean, for the horn players to come up with those parts, they had to have known something... I don't know if you've ever seen horn players walk into a session for the first time where there's no music written down and they're trying to figure out their parts — it's like a traffic jam. And there was none of that going on. The horn players knew the melodies of the songs, they knew what they were going to play. So, while a lot of stuff was worked out in the studio, there's no way they could have worked out all of those parts there, and I don't believe for a second this was the first time they heard that stuff.

"As an engineer, I was trying to get what was in Van's head to come out of the speakers. That always applies to the producer and the leader of the group, and in this case it happened to be one person. One time, I was working with Bob Dylan on a couple of songs where he was singing live with the rhythm section, and he came into the control room on the first playback and said, 'Hey, man, it sounds too good!' When he said that, I absolutely got what he meant. I had cleaned it up too much, I had rolled too much low end off the guitars and vocal and made the bass too clear. When he came back in for the next playback, he then went, 'Yeah! Yeah, that's it! You got it!' All I'd done was put some of the low‑end back, some of the rumble of the room that you'd normally take out. I just let all of that crap stay down there, and he was right, he knows his music. Once I didn't clean it up too much it sounded like Bob Dylan.”

Sympathy For The Record

In the case of 'Moondance', Yakus was dealing with a jazz/folk groove and Van Morrison's sublimely romantic phrasing, as well as a drummer whose use of his kit had to fit with the main man's voice.

"A lot of people make engineer records,” Yakus remarks. "You know, 'Oh, I'm going to make this great-sounding snare drum,' even though it has nothing to do with the voice and nothing to do with the guitar sound. 'I'm gonna make this statement.' The way I learned to make records and the way I became successful making records was to say, 'Here's the sound of the man's voice. Let me get a semi‑finished sound on him. Let me get some reverb in the monitors so I can hear what a finished mix might sound like. Let me get the snare drum to fit with his voice so every time there's a hit it's not a distraction, allowing everything to flow instead of stopping the song because it's so loud or so bright. And let me make sure that the bass drum and the bass go together, so that whole low end on its own is sort of dancing, with the snare drum pushing it.' Those sounds all have to fit together, not only with each other but also with his voice, and the musicians all have to sound like they arrived at the session in the same car.

"The philosophy was the same for 'Moondance'. Everything had to have its place and dance together. The band had to sound like it was swinging. I could have lost the swing of that band had I got the interpretation wrong. In other words, if my interpretation had been that they should be a jazz band or my interpretation had been that they should be a much harder‑sounding rock group, and had I gone in either of those directions — which I absolutely could have done during the recording — it wouldn't have been nearly as effective as what we ended up with.

"As an engineer, I must have a basic understanding of what they're trying to do, not what I want to do. I have to try to get something that not only fits together, but will compete on the radio with other artists while also staying really musical, so it's not hard to listen to. That's what's going through my mind while they're running through the song, and I'm trying to have that sorted out by the time they have the take. With 'Moondance', I remember fooling around, trying to fit the bass drum sound and changing EQ in the middle of the song while they were playing, hoping they weren't going with that take because it would be really hard to fix if that were the case. I just couldn't let it stay the way it sounded, and fortunately, by the time they did get the take, I got myself together and was able to have everything fit.”

Come Together

"We just kept working on 'Moondance' until everybody started to play like one person playing all of the instruments. It's about getting that take where everything comes together. Picture trying to get the take where the band gets it right, the singer gets it right and the horns are perfect — some of those horns were doubled afterwards on an overdub, but otherwise it was like trying to get a bunch of actors to peak at the same time. Still, those guys were really good. If you listen to that record, they had a feel that was raw and finished at the same time, and that's very difficult to do. They weren't trying to do that, it's just what they naturally felt in real life, their natural sensibilities. In fact, if you got a bunch of musicians together today and said, 'Hey, make that sound,' it wouldn't happen. They'd make another sound and it might be very nice, but it wouldn't be the one on that record.

"The guys who played together in that band felt what they felt and it comes across like gangbusters, even 40 years later. That, I think, is the secret to great music. You can play it on your turntable today or your CD player or your iPod, and no matter how many times you hear it — every day, twice a week, year after year — you never get tired of it, because that feel and that honesty come across so strong that they win out over everything. Some albums don't wear well, but others do, and this was one of those albums. Every once in a while it happens. I don't think anyone has an explanation for it, but it comes together, and that's down to the studio, the players, the songs, the performances, the sound, the producer and the engineer — the finished song is like a jar full of marbles, and it takes one marble at a time to make the end product, with each marble having a meaning and a personality. No one thing causes these records to be so special and adored.”

I Can't Take The Pressure

As one of the premier engineers in the industry over the past four decades — in addition to his work as one‑time Vice President of both the Record Plant (NYC) and A&M Studios and, most recently, heading up the development of a new state‑of‑the‑art audio technology for mystudio.net — Shelly Yakus has been involved with projects by a veritable who's who of the rock era. He's worked with John Lennon, Bob Dylan, U2, the Ramones, Tom Petty, the Band, Dire Straits, Madonna, Lou Reed, Stevie Nicks... The list goes on, for the man referred to as Shelly 'I Can't Take the Pressure' Yakus in the sleeve notes to Lennon's 1974 Walls & Bridges album.

"That project took place at the Record Plant, and as engineers there we had the time of our lives,” he now recalls. "However, there was also a lot of pressure on us to get the job done, and so we'd do various things to relieve it, such as chasing each other around with fire extinguishers. The owner, Roy Cicala, actually encouraged us to do those things, and for my part I kept saying, 'I can't take the pressure.' I was only semi‑joking, especially since I was afraid someone might discover I didn't know what I was doing, but it did help to lighten the tension.”

Yakus's studio pedigree goes back a long way. As a young child growing up in Boston, Massachusetts, he worked as a gofer at Ace Recording, the facility co‑owned by his father, Milton, and uncle, and he still remembers asking his dad at age 10 how to use the lathes there to cut clients' lacquers, only to be told, "You need to be able to see over the table.”

"When I was about 14, I could see over the table and I started learning,” Yakus recalls. "I learned the basics, the foundation for everything that I'd learn throughout the rest of my life from people who were gracious enough to teach me and spend time with me.”

After learning to edit as part of his apprenticeship at Ace during the mid‑1960s, Yakus made his way to New York City and, in 1967, secured a job as an assistant at producer/engineer Phil Ramone's then‑ultra‑popular A&R Recording.

"On the first session, I was basically an assistant to an assistant,” Yakus recalls with a laugh. "I'll never forget his name; it was Major Little, and he just wanted to be an assistant engineer. He had no desire to be an engineer, he just wanted to be a great assistant, so they put me with him and he taught me how the engineers — who were all on staff back then — set up the studio and why they did it that way. My first day of work with him was for a Dionne Warwick session produced by Burt Bacharach, and they did three songs in three hours with a 35‑piece orchestra, including 'Alfie' and 'Valley of the Dolls'. It was incredible. Phil Ramone was the engineer, and I still get chills remembering the moment when I first heard that sound.”

Experiments At The Record Plant

After a few years at A&R Recording, Shelly Yakus relocated to New York's Record Plant, where he reunited with Roy Cicala, who had also been at A&R.

"He was a big inspiration to me,” Yakus remarks. "He did rock & roll, and I was very interested in that. He understood it, he knew how to make great‑sounding rock & roll records. He was so inventive. He used to say to me, 'The rule is there are no rules.' Sometimes, when I was his assistant, he would cover the meters with pieces of white paper and then draw the needles on them so that they were pointing at five o'clock to make sure I'd leave him alone. He really taught me to use my ears instead of reading books about what's possible and what's not possible. When I would tell him he was hitting +3, he'd say, 'Well, how does it sound?'

"We used to do a lot of experimenting, where we'd have a shotgun microphone over the drums, 20 feet in the air, or we'd get an old oil drum, tape headsets to the outside of it, place a mic on the inside and record the sound reverberating. One time, Roy said to me, 'Listen, I want you to go to the drug store and get a pack of rubbers. I want to put one on this microphone so that it doesn't get ruined when I place it inside a glass milk bottle filled with water. Then we'll tape headsets to the side of the milk bottle, send the drum sound in there and see what happens.' That turned out to be awful‑sounding, but the oil drum was pretty good and the stairway was pretty good, and we used to do crazy things that worked, whereas today people just twist the knobs. I don't want to say that they're not making great records — once in a while, one comes along — but I have to tell you that, for me personally, it's disappointing to turn on the radio and feel like one person is mixing all of the records and one producer is making them in the same studio. It all sounds kind of fabricated.

"Today, people confuse new with better, and I don't necessarily go with that. It's not that I'm old or thinking like my father — I don't want to say, 'Ohhh, the analogue days!' I do like to use a combination of analogue and digital. But the truth is, in my opinion you need transformers to be able to capture what's in a room. Without them, it always sounds like a thin representation. When I look back at the equipment that was used, it was so very basic, but the successful studios all had fabulous‑sounding rooms. You opened up a mic and it sounded like music. You didn't have to do a whole lot to it.

"You had to really be clever to get something sounding unique. Anybody could balance a song, and it would sound nice and marketable, but to cross that line and really come out with something special you had to experiment a lot. This would either be at a different time to the session, so that you had your chops together, or the producer would allow you to experiment at the session itself.

"I'm not saying my way is the only way; I'm just saying it works for me. Recording is a philosophy within itself. If you drive to California from Arizona, a lot of roads will get you there, but you always end up in California, and it's the same when it comes to making a great record. Ten good engineers might do it in 10 different ways, but they will end up in a good place, and that's all that matters.”