Paul Simon's Graceland album combined a huge mixture of musical styles and was recorded in studios all over the world. The man responsible for putting it all together, both sonically and physically, was Simon's long-time engineer Roy Halee. This is how he did it...

Roy Halee hasn't only worked with Simon & Garfunkel, you know. Bob Dylan, the Byrds, Barbra Streisand, Blood Sweat & Tears, Moby Grape, the Yardbirds, the Lovin' Spoonful, Neil Diamond, Edie Brickell, Boz Scaggs, Willie Nelson, the Roches, Laura Nyro, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Journey, Rufus and Chaka Khan... The list is an eclectic one, and it goes on and on with regard to a Grammy-winning production/engineering career that has spanned more than 40 years. Nevertheless, it is Halee's historic body of work with S&G — recording all of their albums, co-producing a couple of them, and also co-producing and/or engineering many of Paul Simon's solo records — that has justifiably earned him his legendary status.

Roy Halee hasn't only worked with Simon & Garfunkel, you know. Bob Dylan, the Byrds, Barbra Streisand, Blood Sweat & Tears, Moby Grape, the Yardbirds, the Lovin' Spoonful, Neil Diamond, Edie Brickell, Boz Scaggs, Willie Nelson, the Roches, Laura Nyro, Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Journey, Rufus and Chaka Khan... The list is an eclectic one, and it goes on and on with regard to a Grammy-winning production/engineering career that has spanned more than 40 years. Nevertheless, it is Halee's historic body of work with S&G — recording all of their albums, co-producing a couple of them, and also co-producing and/or engineering many of Paul Simon's solo records — that has justifiably earned him his legendary status.

The Early Years

A native of Long Island, New York, who initially studied to be a classical trumpet player, Roy Halee began working for CBS Television in Manhattan during the late 1950s, positioning cameras and boom mics before handling the audio of live network shows such as The $64,000 Question. When CBS relocated its TV production to Hollywood, Halee was the victim of a union layoff, yet a walk across the street to Columbia Records resulted in his spending the next 18 months editing pop and classical recordings, while also mixing down three-track tapes to stereo and mono in preparation for mastering. Eventually growing tired of this work, he was transferred from the editing cubicle to the studio, where his first session was Dylan's 'Like A Rolling Stone'. Paul Simon with collaborators Ladysmith Black Mambazo on the Graceland tour 1987.

Paul Simon with collaborators Ladysmith Black Mambazo on the Graceland tour 1987.

"That was very fortunate, because at the time Columbia didn't have any rock & roll artists, per se," Halee remarked when I first interviewed him back in 1997. "They either dealt with classical or what they called 'legit pop acts' such as Tony Bennett and Johnny Mathis. Dylan, on the other hand, was their first folk-rock act, and on the strength of that job I got a bit of a reputation in the city. A six-minute single was unheard of at that time, and basically I don't think they really liked it at Columbia Records. It was foreign to them, but then, when the damned thing took off, it turned a lot of heads and he exploded.

"You see, although I was a classically trained musician, I had more fun doing rock because I could experiment with sound. You couldn't with classical, at least not at Columbia. This is where the microphones went and you couldn't change anything, and that was the way it was."

Accordingly, while still at Columbia, Halee began working with outside clients for the Kama Sutra label, including the Lovin' Spoonful on hits like 'Summer In The City'. And he also recorded the Yardbirds' version of 'I'm A Man' with Jeff Beck on lead guitar. The fact that Beck used a small amp at low volume settings impressed Halee, not least because this was contrary to what many of his contemporaries were doing at that time.

"The sound in the control room was, of course, enormous," Halee recalled. "Evidently they were hip to the idea that if you play a little softer with greater dynamics you get a bigger sound when it's recorded. I myself always made musical suggestions when I was taking care of the technical side, but in those days that was expected of us, and Columbia didn't even give engineering credits."

Ditto certain sessions that featured Roy Halee in the producer's role. Such was the case with Peaches & Herb.

"There was no other producer around, and I never got an engineering or a production credit!" he remembers. "Still, I'm not bitter about that, you know, because that was part of the gig, that was part of the training, and I was grateful to be able to do it. I was having a good time, getting a lot of experience doing a lot of different acts. Jazz, rock, classical — man, you name it and I was able to get my hands on it. I even worked on show material with 40-, 50-, 60-piece bands, a chorus, and soloists all live. It was invaluable. These days I think it's almost impossible for an engineer to have that many opportunities."

I Got Two Folk Singers & A Microphone

Roy Halee with Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel in the control room of Columbia's New York studio.It was actually thanks to Simon & Garfunkel that Halee began to get the credit he deserved. Having first encountered them in 1964, when the duo auditioned for Columbia in-house producer Tom Wilson, he collaborated with Wilson in June of the following year on the overdubbing of electric guitars, bass and drums onto the acoustic version of 'The Sounds Of Silence' that had appeared on their debut album, Wednesday Morning, 3am. These overdubs, performed by Bob Dylan's studio band without the knowledge of S&G, transformed a folk number into folk-rock and resulted in a chart-topping single — reuniting the pair, who had split up following their aforementioned album's initial failure. What's more, it also led to a 'Sounds Of Silence' follow-up, released in January 1966, which gained Simon & Garfunkel international recognition and launched their working relationship with Roy Halee.

Roy Halee with Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel in the control room of Columbia's New York studio.It was actually thanks to Simon & Garfunkel that Halee began to get the credit he deserved. Having first encountered them in 1964, when the duo auditioned for Columbia in-house producer Tom Wilson, he collaborated with Wilson in June of the following year on the overdubbing of electric guitars, bass and drums onto the acoustic version of 'The Sounds Of Silence' that had appeared on their debut album, Wednesday Morning, 3am. These overdubs, performed by Bob Dylan's studio band without the knowledge of S&G, transformed a folk number into folk-rock and resulted in a chart-topping single — reuniting the pair, who had split up following their aforementioned album's initial failure. What's more, it also led to a 'Sounds Of Silence' follow-up, released in January 1966, which gained Simon & Garfunkel international recognition and launched their working relationship with Roy Halee.

"Right from the start, I loved their sound because it had a classical feel," he now says. "It was very beautiful, very legitimate, with these two voices on one microphone. They never worked with two separate microphones, never. It would not work. You couldn't use two [Neumann] M49s, separate those voices and then mix them together."

Halee also acknowledges how much both Simon & Garfunkel helped him by embracing the concept of the producer-engineer:

"At that time, engineers were not producers and producers were not engineers. You could work with bad producers, but there were also some very, very good producers who did their schtick — which was the music — and basically left the engineering to the engineer. Simon & Garfunkel, on the other hand, obviously felt that I was really producing their records with them and that I should be credited for this and paid a royalty.

"Aside from Tom Wilson, both Bob Johnston and John Simon had also produced them. In fact, Bob Johnston produced Dylan, too, and at that time I was on practically all of Bob's sessions. I thought he was a good producer; very exciting, he got a lot of emotion going in the studio, which impressed me at that time as other producers were not getting the musicians fired up. There's a certain talent in that. And John Simon had the finest ears of any producer I ever worked with. Still, for whatever reason, Paul and Artie wanted to make their records with me... I could get involved musically, and I started to get very close to Paul, who would bounce songs off me — 'What do you think of this? What do you think of that?' and so on — and things therefore evolved to the point where I was a member of that group.

"On 'The Boxer', for instance, it was my idea to put the brass and voices on the end and to mix the pedal steel with a piccolo trumpet part. That was a very interesting sound and blend, with the pedal steel recorded down in Nashville and the Bach piccolo trumpet done in a church at Columbia University, where all of the voices and brass were overdubbed. We therefore used two remotes to achieve one sound, and for me that was really interesting, as was the fact that the strings were wild-tracked in at the end of the mix. It was also the first time we used Dolbys on a remote.

"Musically, engineering-wise, we were a team, and as a result of that we were able to do a lot of innovative things. You know, linking up two eight-track machines to make 16, and going out and making work tapes. The second eight-track would be used as a work tape to go and overdub voices in the church; do it as a remote, bring it back to the studio and overdub on it. That wasn't being done at the time, so it was great. It was innovative and very, very creative from an engineering standpoint. Not to mention the enormous contributions of drummer Hal Blaine, multi-instrumentalist/arranger Larry Knechtel and bass player Joe Osbourne."

Out Of Africa

It was also pretty rewarding, garnering Halee a 1968 Grammy for the song 'Mrs Robinson' and three more in 1970 for 'Bridge Over Troubled Water' and the album of the same name. Then, when S&G split, he continued working with them on their solo projects, which in Paul Simon's case included his eponymous first album (1972), as well as There Goes Rhymin' Simon (1973), Hearts & Bones (1983) — which was originally conceived as a Simon & Garfunkel collaboration following their successful, Halee-recorded reunion concert in New York's Central Park a couple of years earlier. And then, in 1986, Graceland, which signalled not only a stunning, artistically experimental return to form, but also a major change of direction for the singer/songwriter/guitarist in terms of both the pop-infused, Zulu-based mbaqanga music of South Africa and his approach to recording it.

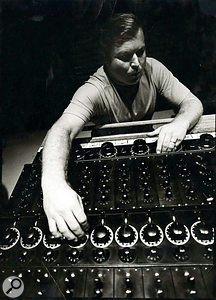

Roy Halee at the desk in Columbia, mid-'60s. They really don't make them like that any more."For me, that project started with Paul telling me, 'Roy, I've got to play you something that is just great,'" Halee recalls as we now sit in the basement music-room of his home in Boulder, Colorado. The 'something great' was a cassette recording of the Boyoyo Boys instrumental, 'Gumboots', lent to him by singer-songwriter Heidi Berg, which he would subsequently re-record with his own lyrics. "It was the most infectious thing I'd ever heard, as catchy as hell," Halee continues. "He said, 'We have to go over there and record it.' I said, 'Where?' 'South Africa.' 'OK, great.'"

Roy Halee at the desk in Columbia, mid-'60s. They really don't make them like that any more."For me, that project started with Paul telling me, 'Roy, I've got to play you something that is just great,'" Halee recalls as we now sit in the basement music-room of his home in Boulder, Colorado. The 'something great' was a cassette recording of the Boyoyo Boys instrumental, 'Gumboots', lent to him by singer-songwriter Heidi Berg, which he would subsequently re-record with his own lyrics. "It was the most infectious thing I'd ever heard, as catchy as hell," Halee continues. "He said, 'We have to go over there and record it.' I said, 'Where?' 'South Africa.' 'OK, great.'"

To that end, Simon had already established contact with one Henry Rosenthal, who'd grown up listening to the Beatles and the Rolling Stones in a white, middle-classed section of Johannesburg, yet who had spent the last few years combining Zulu music with Western pop when producing local artist Johnny Clegg for Rosenthal's own record company, Music Inc.

"Hilton knew everybody in Johannesburg," Halee explains, "and so he was able to garner all of these musicians who we'd never previously seen or even heard of. He also booked the recording sessions at Ovation, where they'd mostly been doing South African gospel, and that was a good studio. I remember walking in there and thinking, 'This is the best-sounding control room I've ever been in.' There was a Harrison console, 3M tape machines and modified James Lansing monitors that made it sound like you were in your living room. I'd expected a horror show, but everything worked and my first impression was, 'This is very comfortable.'

"Having said that, the studio itself was like a garage, and in that regard I thought it could be a problem, especially since we were going to record jam sessions from which songs would be created. As I soon found out, the musicians liked to work very close together, with eye contact to get the feel and the groove going. However, since the songs would be crafted out of these grooves, the instruments had to be isolated so that we could do plenty of editing: repairing parts, pulling out a specific guitar, and so on. We had to have the flexibility to erase. This is where my experience at Columbia came into play. There are ways of setting up a rhythm section and getting good isolation without putting the musicians in separate little booths with headphones. The right choice of microphones and levels really helps, and in this case I recorded the musicians with very few baffles — none around the drums — while they stood close together with good eye contact.

"Nobody wore headphones, aside from the drummer, and even he often didn't wear them. You see, most musicians prefer to not wear headphones, because otherwise they have to listen to this mix that is generally horrible. Everybody's saying, 'Can I hear more of myself?' and there's this nightmare going on. Well, I wasn't about to get into that with these people. They were to come in, play and feel comfortable while my job was to get some isolation.

"For the Graceland sessions, built-in isolation was right there, along with built-in foldback, and I was very careful about the level. It was comfortable without being screamingly loud. I was only working with one guitar and one bass, and both were right next to the drummer. That setup enabled us to take the tapes back to New York and redo certain parts."

Digital Vs Analogue

At the Hit Factory, Halee sat behind an SSL console, used a Sony PCM3324 digital multitrack, and monitored on United Western speakers which he describes as "unlistenable. They were totally wrong, with no bass and the top end just screaming at you. I raised so much hell there, they hated to see me arrive. I'd ask, 'Can you voice these speakers, please?' and they would, but then another session would come in at night and somebody would change them! Unlike at Columbia, there were no standards whatsoever. You never knew what you were going to hear, and anything you did hear bore absolutely no relationship to what was on the tape. So, I brought in my own speakers — a pair of little Westlakes that we kept there — and everything was fine."

As things turned out, the most laborious and time-consuming aspects of the Graceland project took place at the Hit Factory.

"The amount of editing that went into that album was unbelievable," Halee asserts. "We recorded everything analogue, so it sounded really good, but without the facility to edit digital I don't think we could have done that project. The first thing I did was take the material to New York and put it on the Sony machine. Then we edited, edited, edited like crazy, put it back on analogue, took it to LA to overdub Linda Ronstadt or whoever, brought it back to New York, put it back on digital and edited some more. We must have done that at least 20 times, and if not for digital we could have ended up with just as many generations of recordings."

Just A Kid From Soweto

"The drummer was placed where he usually is in that studio, in the far right corner, because I wasn't about to enter a strange studio and say, 'Let's the put the drums there.' I'd rather rely on the resident engineer where he puts them, and as I recall this was in the far right corner. The guitarist, Ray Phiri, was very close to him, facing his own amplifier. That stemmed from my time at Columbia, where I'd have four guitarists right in front of the drums, all with their amplifiers facing them. That way I didn't need to use gobos. I'd come from a school where I couldn't use a lot of them when doing live sessions in New York. The musicians would have said, 'What is this? You can't hear anybody.' In my opinion, the musicians have to be comfortable and able to see each other. The drummer in his own little room with headphones just doesn't make it for me."

Roy Halee at home in his music room in Boulder, Colorado, where Grammy Awards stand against a backdrop of gold and platinum records. Pride of place goes to the loudspeakers that he describes as "the best in the world": a pair of Wilson Audio X2s. These are linked to a Boulder amplifier — again described as "the absolute best". As for those recordings themselves, Paul Simon allowed the musicians to do their thing, provided his own input and then took his time deciding not only which contributions to use, but also how to use them in terms of actually shaping the songs.

Roy Halee at home in his music room in Boulder, Colorado, where Grammy Awards stand against a backdrop of gold and platinum records. Pride of place goes to the loudspeakers that he describes as "the best in the world": a pair of Wilson Audio X2s. These are linked to a Boulder amplifier — again described as "the absolute best". As for those recordings themselves, Paul Simon allowed the musicians to do their thing, provided his own input and then took his time deciding not only which contributions to use, but also how to use them in terms of actually shaping the songs.

"Paul certainly wasn't going to tell those guys what to play," Halee remarks. "The sessions had to take place within certain hours before the bus came to take them all away. Paul is a master organiser, he's extremely smart, and he was great at determining which section would be nice as a bridge or a chorus or an intro while striking up friendships with the group members with whom he could communicate. These included the guitarist Ray Phiri, who always had a wealth of stuff going on in his head. He was smart, he could tell what Paul liked, and he would just go into the little catalogue in his mind and come up with something. Of course, he played guitar on everything.

"Whenever Paul said, 'What do you have, Ray?' the response would be 'Well, I have this...' He's a really quiet, unassuming gentleman, and yet he was the catalyst for so much that took place, along with the bass player Baghiti Khumalo. Bhagiti is now world famous, but back then he was just a kid from Soweto. He played a fretless Washburn bass in tune — recorded with a combination of direct and amplifier, picked up by a dynamic mic— and talk about spot-on. He was unbelievable. For me, those sessions were all about the bass. It always seemed so powerful, and whenever Paul and I came back to New York and listened and listened and listened to the material, it was the bass that really turned me on. Take the bass line on 'Boy In The Bubble' — oh, man, it's off-the-wall great. And you should hear some of the out-takes. Even today, there could be two instrumental albums consisting of those fabulous grooves.

"That's how the songs really evolved. Paul has great musical ears, and when it came to sifting through all the material and deciding what to use, where to make edits and how to shape things into a track, he had a lot of that in his head. He has an incredible mind, and there wasn't anything that he didn't make a mental note of while listening to the musicians play their grooves. Paul Simon is one in a million. Once you work with him, you don't want to work with anybody else. For my part, I have good ears, and on this album I had a lot of input, but this was his baby. He heard this. I wouldn't have dreamed about going to South Africa or thought, for instance, that Linda Ronstadt would be great duetting with him on 'Under African Skies'.

Comp Like Crazy

"When we arrived in Johannesburg, the only song Paul had was the 'Gumboots' demo. The 'Homeless' track with Ladysmith Black Mambazo was written by [founder and musical director] Joseph Shabalala — it was part of their repertoire — but Paul wrote the lyrics and played various guitars, as was also the case with 'Diamonds On The Soles Of Her Shoes'. The lyrics, in turn, caused a big problem. A lot of the album's songs are very wordy — they come at you like gangbusters — and the arrangements were also involved, but at the same time it was supposed to be a pop record and people had to understand the lyrics. That was tricky, both for Paul to enunciate them and for everyone else to hear them."

Although some of the lyrics were written in the studio, the vast majority of them were composed by Simon over the course of a work-intensive month at his home in Montauk, New York. These, in turn, necessitated plenty of rewrites due to the often overly complicated words.

"While practically all of the overdubs were done in the control room of the Hit Factory in New York — making communication with the musicians a hell of a lot easier — the vocals were tracked in the studio there," Halee explains. "For microphones, we used the usual selection of tube Neumann 49s, 87s and 67s. In fact, Paul's mic always seemed to end up being a tube 67 thanks to how it helps with sibilance, enunciation and all-around fullness. I tried different mics with him through the years, but I always went back to the standard M49 or U67.

"Capturing Paul's vocals was always very, very tough. Not because of his ability, but because he's a perfectionist. And me, too. I have very good ears for intonation and rhythm, and so he would go out and sing the same vocal 15 times and then I'd comp like crazy. I'd say, 'Let's do this line over,' or 'This word sounds a little sharp,' and so he'd re-sing the entire song just so that I could quite literally take that word."

The upside to this reciprocal passion for perfection has been the mutual trust in the working relationship between Paul Simon and Roy Halee, even if it took a long time to establish and, in the final analysis, the latter will ultimately defer to the former's opinion.

"He's usually right," Halee concedes. "However, if I'll tell him something's out of tune, he'll just say, 'Fix it,' and leave me to it. That takes a lot of trust."

It's All About The Tape Delay...

"Throughout the Graceland project I tried to capture the integrity of the South African sound, not my own sound, and managed to pick up some of their very interesting ideas. One of these was that they'd use a small amount of very short chamber to the bass, and it was great. It worked very well with Baghiti's fretless bass. I put all kinds of tape reverb and delay on the synth bass line to make it do more than it was actually doing. I used three or four tape machines with different tape delays, and if you listen to that part it's jumping all over the place. It's great fun, a bit like Hal Blaine's bass drum on [Simon & Garfunkel's] 'Bridge Over Troubled Water'. He's not really playing that part, but different tape delays made it come out that way. The same applies to Hal's conga part on 'The Boxer', where I opened and closed by hand the return of a room echo chamber — It's like a door opening and closing. Quite an interesting sound.

"They almost threw me out of Columbia Records in Hollywood for doing that type of thing. I had machines lined up all the way down the hall, using tape reverb and delay on different Simon & Garfunkel recordings, like 'Mrs. Robinson'. I couldn't do the same with an EMT 140. All my life I loved to experiment with those machines and different delays."

Which was fortuitous for Paul Simon when he opted to lay down a lyrically complex vocal amid all of the different sounds on the busy, extremely involved track that was 'You Can Call Me Al'. His attitude: "We've got to make this work." And Roy Halee did, after initially feeling exasperated and then labouring on it for quite awhile.

"What I came up with was a tape delay feeding the left channel and a different delay feeding the right," he says. "All of a sudden his vocal receded into the track, at least to some degree, and we could understand the words! Don't ask me why, but it worked, and I couldn't have done that with an echo chamber or EMT 140. In fact, remove that tape delay from 'You Can Call Me Al' and, what with all of the sibilance, pops and other little mouth noises against what was going on in that track, the vocal would be unintelligible.

"It's all about mixing the sound, and it's also about the material being well recorded and using the leakage to your advantage. How many times throughout my career have I heard, 'Oh, that's OK, we'll fix it in the mix'? In a lot of cases you can't fix it in the mix. A lot of the tape reverb and delay ideas I used came from Les Paul. He was a master at that, he built a career on it. It's amazing what you can do with tape machines, or at least it was in those days when there was no magic box to help you out."

All Around The World

In all, about two weeks were spent recording the basic rhythm tracks at Ovation in February 1985 before returning to the Hit Factory home base for edits. Then it was planning the next move in terms of personnel and locale, be it London's Abbey Road for 'Homeless' in October of that same year or LA's Amigo Studios for Linda Ronstadt's vocal on 'Under African Skies' and 'All Around The World Or The Myth Of Fingerprints' with Los Lobos. The Hit Factory recording sessions took place in April 1986.

One of the tracks recorded entirely at the Hit Factory was the album's first single, 'You Can Call Me Al', whose lyrics dealing with identity crisis were inspired by a party that Paul Simon had attended with then-wife, Peggy Harper, where the host mistakenly addressed them as 'Al' and 'Betty'. For Simon, this turned out to be a happy accident. For the record company, it turned into a chart hit, thanks in part to an amusing promo video that features comedian Chevy Chase lip-sync'ing the lead vocal while the man who actually recorded it performs several of his band members' instrumental parts.

While Simon also contributed backing vocals and six-string bass, the line-up for 'Al' comprised Chikapa 'Ray' Phiri on guitar; Baghiti Khumalo on bass; drummer Isaac Mtshali; percussionist Ralph McDonald; synth player/arranger Rob Mounsey; Adrian Belew on guitar synth; Ronald E Cuber playing bass sax & baritone sax; trumpeters John Faddis, Ronald E Brecker, Lewis Michael Soloff and Alan Rubin; trombonists David W Bargeron and Kim Allan Cissel; and Morris Goldberg performing the pennywhistle solo.

"It was my idea to end the tune with the excitement of having live horns playing the part that had already been played several times by Rob Mounsey on the synth," Roy Halee recalls. "I then also doubled that part by sync'ing them back in at the mix stage. However, it was Rob who wrote it down for the horns. It was his arrangement, and the groove that's going on in that song is Rob's groove. He played the groove in the verses, as well as the synth lines at the beginning and throughout the number, and it was that groove which turned the song into a monster, although the brass contributed quite a lot, too."

Meanwhile, the distinctive bass solo that Simon is seen playing in the aforementioned video was actually recorded by Baghiti Khumalo on his own birthday: a one-measure descending line that, in order to extend the break, was later reversed and played backwards in order to add the ascending line.

"I simply copied the line as originally played to a mono machine and then sync'ed it backwards into the multitrack," Halee explains. "That kind of thing was always happening — 'Let's try it in reverse.' We would wild-track all the time. Anything to make it sound more interesting."

Graceland

As it turned out, the Graceland mix, carried out in the same control room at the Hit Factory, took an average of about two days for each song. Much of the tape reverb and delay added at this stage had already been employed by Halee during the recording sessions in order to motivate the musicians. He just didn't put it down on tape if he wasn't yet sure about the final outcome. And once he was sure, and the album had been completed, it met with a less-than-enthusiastic reception from the record company honchos.

"Paul had tremendous faith in the record," says Halee, "although I had my doubts, because it had been such a lengthy, difficult project, and the music was so different to what was on the charts. Those bass grooves just weren't happening at that time.

"Just listen to 'The Boy In The Bubble'. For me, the bass line and the feel of that tune is what the album is all about. It's the essence of everything that happened. The guitar, the drums and that incredible bass add up to a feel going on at the bottom end that is unlike anything I've heard before or since. It's a major part of why the record was huge."

So huge, in fact, that Graceland became Paul Simon's most commercially successful album, being certified five times platinum by the RIAA en route to selling more than 14 million copies and peaking at number three on the Billboard chart following its release on August 12, 1986. In the UK it went all the way to number one. In 1987, having drawn worldwide attention to the music of South Africa, it won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year, and this was followed by the title track scooping that for Record of the Year. Meanwhile, 'You Can Call Me Al' reached number four on the UK singles chart, but only 44 in America after its October 1986 release. Reissued there the following March, it eventually peaked at 23. Arguably its finest hour came when the track was utilised by Al Gore during his bid to become Vice President alongside Bill Clinton in 1992.