Recording the White Album was a major project by any standards, not least for Ken Scott, who, at the age of just 21, found himself engineering the biggest band in the world...

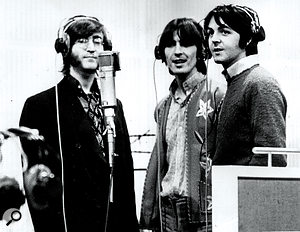

John Lennon, George Harrison and Paul McCartney gathered around a Neumann U47 in Abbey Road, 1968. Photo: Getty Images

John Lennon, George Harrison and Paul McCartney gathered around a Neumann U47 in Abbey Road, 1968. Photo: Getty Images

The Beatles' eponymous 1968 two‑disc LP, popularly known as the White Album, was a turning point for the group. For the first time, personal tensions intermingled with artistic differences between the band members, sometimes creating an unhappy atmosphere in the studio, but also shaping a musical dynamic that John Lennon subsequently likened to "just me and a backing group, Paul and a backing group”.

The Beatles had written a number of new songs during their February to April 1968 trip to Maharishi Mahesh Yogi's ashram in Rishikesh, India to practice transcendental meditation. They initially recorded demo versions 23 of them on a four-track machine at George Harrison's home in Esher, Surrey. Nevertheless, once the White Album sessions commenced at EMI's Abbey Road facility at the end of May, the Fab Four sometimes recorded their material separately and simultaneously in all three of its studios.

Meanwhile, the tradition that wives and girlfriends stayed away from their men's work domain was breaking down, as John's new partner Yoko Ono was now constantly by his side. Her influence soon became evident in some of his new compositions — not least, the musique concrète sound collage 'Revolution 9' — yet her presence also added fuel to the flames of the growing disharmony.

On 22nd August, a disgruntled Ringo Starr quit the group, necessitating his three colleagues to fill in on drums for the recording of 'Back In The USSR' and McCartney to do the same for, amongst others, 'Dear Prudence'. Starr returned to the fold a couple of weeks later, yet his temporary departure only echoed the longer-term exit of engineer Geoff Emerick. Fed up with the Beatles' in-fighting and increasingly churlish attitude towards himself and George Martin, Emerick walked out during the recording of 'Cry Baby Cry' in mid-July.

Emerick's creative ingenuity, first palpable on the ground-breaking Revolver album in 1966 and rewarded with a Grammy for the landmark sound of Sgt Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band the following year, wouldn't manifest itself on another Beatles record until their 1969 swansong Abbey Road. Ken Scott was the first man to take Emerick's place behind the console, engineering two thirds of the tracks on the White Album.

What Rot?

A young Ken Scott operating a cutting lathe at Abbey Road. Mastering formed a part of his apprenticeship at the studio.Photo: EMI Records

A young Ken Scott operating a cutting lathe at Abbey Road. Mastering formed a part of his apprenticeship at the studio.Photo: EMI Records

Although, as George Harrison would later assert, "the rot had already set in”, there can be no denying the outstanding quality and sheer breadth of the 30 tracks that ended up on the White Album. Incorporating a wide sampling of the Beatles' musical tastes and influences, it showcased them diving headlong into rock, pop, proto-punk, heavy metal, blues, folk, country & western, music hall and the avant garde. What's more, while the picture that's normally painted of the project is a gloomy one — highlighting the discord that would boil over during the disastrous and destructive January '69 sessions for the Get Back album and documentary (ultimately retitled Let It Be) — Ken Scott's recollection of the sessions with which he was involved is altogether more upbeat.

"An awful lot has been written about the Beatles being at odds with each other the entire time they were recording the White Album, but that to me is completely false,” says Scott, who has documented his studio experiences in a new book, Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust, co-written with Bobby Owsinski. "Most certainly, they acted as backing musicians for each other up to a point, but there were also times when they were closer than they'd been in ages. After Ringo quit the band and then returned, suddenly they were a band again. They were so close, it was amazing, and we got more work done during that period than they'd previously done in months.

"You've got to take into consideration, they were working on that album for close to six months, and there isn't a project I have worked on — even a two-week project — where at some point someone hasn't lost their temper. So, spread that over six months and it's going to happen a few times. But I repeat, it wasn't that bad. And there were also outside influences that people don't take into consideration. We were working on 'Hey Jude', and the first night, when everyone was up and the Beatles were still sorting out the arrangement, a couple of guys came by the studio because the next night there was going to be a film crew coming in for a documentary [Music!] being made by the National Music Council of Great Britain. 'Don't worry,' they told us. 'We'll be in tomorrow but you won't know we're here.' Yeah, right.

"The next night, the film crew came in and of course they were in everyone's faces. Well, there ended up being a huge row between George and Paul — George was playing a guitar phrase that responded to each of Paul's vocal lines and Paul vetoed it. However, this wasn't because the band members weren't getting along; it was because the outside sources were putting everyone on edge, someone was going to blow his top and it just happened to be those two.

"For my book, I did an interview with Chris Thomas, who at that time was George Martin's assistant. When Chris came back from a holiday [at the end of the first week of September '68], there was a note from George [Martin] saying he had also gone on vacation and that Chris should go along to the studio and help out. Suddenly, having never produced anything in his entire life, Chris was the Beatles' producer. Still, when I ended our interview with the standard 'Is there anything else you would like to say?' Chris's immediate comment was, 'Yeah, please let everyone know it was fun; it was nowhere near as bad as has been stated. We loved it.' So, there are several of us who don't see it the same way as other people. We had a blast. It was great.”

Career Progression

The Studio Two control room. The REDD mixing desk in the centre is of a type used on all but one of the Beatles' Abbey Road recordings. Photo: EMI Records

The Studio Two control room. The REDD mixing desk in the centre is of a type used on all but one of the Beatles' Abbey Road recordings. Photo: EMI Records

Born and raised in Southeast London, Ken Scott acquired a tape recorder for Christmas when he was 12 years old in 1959 and immediately began capturing radio material from the BBC Light Programme's Pick Of The Pops, which was then broadcast at around 10:40 on Saturday nights. However, it was a Wednesday, 20th March, 1963 transmission of Here Come The Girls — an ITV series hosted by Alan Freeman, focusing on the recording exploits of assorted British female pop artists — that proved to be the turning point for the teenage Mr Scott.

"The episode featured a young lady who I had the hots for at that time,” he recalls. "Her name was Carol Deene, and while I saw her singing into a mic the camera panned up to this huge window where a guy was sitting behind a console and looking down towards the main studio. When I discovered he was a recording engineer, that's what I had to be. It turned out this took place in Studio Two at Abbey Road and behind the window was a man by the name of Malcolm Addey, who eventually became one of my teachers.

"It wasn't long before I grew fed up with school. So, one Friday evening I wrote a bunch of letters; they were mailed on the Saturday, I received a reply from EMI on the Tuesday, had an interview on the Wednesday, left school on the Friday and started work the following Monday, 27th January, 1964. In nine days it all came together.”

Not only that but, following a stint in the EMI Studios tape library, Scott's first gigs as an assistant engineer were the 1st and 2nd of June '64 recording sessions for several tracks on the Beatles' A Hard Day's Night album and Long Tall Sally EP. This, of course, was the soon-to-vanish era when it was normal to complete four songs in three hours, and thereafter Scott fulfilled the same role, assisting engineer Norman Smith on tracks for the Beatles For Sale, Help! and Rubber Soul LPs through November of 1965.

Then, in March 1967, while Ken Scott's comprehensive apprenticeship included work as a mastering engineer, he assisted Geoff Emerick on the recording of the Sgt Pepper tracks 'She's Leaving Home' and 'Getting Better', before debuting as a full-scale engineer that September on the Magical Mystery Tour EP cuts 'I Am The Walrus', 'The Fool On The Hill' and 'Your Mother Should Know', as well as on the single 'Hello Goodbye'.

"My first session as a second engineer for the Beatles had been scary, but my first session as an engineer with them was absolutely terrifying,” Scott remarks. "Up until then, not allowed to touch mics or anything, I'd learned recording techniques by mostly sitting and watching. There were three pop engineers at Abbey Road during the time I was assisting — Norman Smith, Malcolm Addey and Peter Bown — and then the great thing was I got to see how three incredible classical engineers worked as well: Chris Parker, Bob Gooch and Neville Boyling. Still, once I got the call to engineer, it was as if I'd been dropped in the fire, especially since I was now on my own to record the biggest band in the world. It was a case of sink or swim, and luckily I swam.

"The Magical Mystery Tour project came just after the death of [Beatles manager] Brian Epstein and the whole thing was un-together. I hate to use the word 'floundering', but that's almost what was going on, whereas for the White Album their heads were a little straighter. Considering the drugs that were being taken, this may seem hard to believe, but I think by then they'd come to terms with Brian's death and they appeared to have a much better idea as to what they should be doing.”

The now legendary Studio Two live room. Photo: EMI Records

The now legendary Studio Two live room. Photo: EMI Records

The Great Tape Recorder Robbery

When the White Album sessions commenced at the end of May 1968, Studio Two's upstairs control room housed an eight-input, four-output EMI REDD 51 console and a Studer J37 four-track tape machine. Studer were still developing their A80 at the time, but eight-track was on the horizon in the form of two 3M M23 machines imported from America as part of EMI's ongoing attempt to keep up to date. These underwent the usual, exhaustive quality checks by the studio's technical experts who, insisting that everything conformed to their high standards, concluded that certain modifications would need to be made before said machines were fit for use.

It was while these tests were being carried out that the Beatles recorded 'Hey Jude' and 'Dear Prudence' on eight-track at the independent Trident Studios in Central London. So, when George Harrison came across one of the 3Ms sitting in a corridor at EMI, he immediately told Ken Scott that the machine should make its way to the Studio Two control room, and Scott assigned tech engineer Dave Harries the task of ensuring this happened without being granted permission by the studio bosses.

"The next day, Dave and I were reamed new rear ends,” Scott recalls. "George Martin was away and it wasn't until much later that I found out he not only knew EMI had acquired the eight-track machines, but that he'd actually been asked if he wanted to use them on the White Album sessions and had said no. This was because George knew the Beatles would hit the roof when they discovered that, without the 3M being modified, they couldn't do many of the things that they'd been used to doing on four-track... and they did.”

Early Versions

Ken Scott today at Abbey Road.

Ken Scott today at Abbey Road.

The group's very first eight-track recordings at EMI were some of the overdubs on 'While My Guitar Gently Weeps'. This began life on four-track when, on 25th July, 1968, George Harrison rehearsed his new composition with his band mates before taping a solo version that was very different to that which ended up on the album. This early version boasted an extra verse and featured just George singing and playing a Gibson acoustic guitar (miked with a Neumann KM56), alongside an organ part that was overdubbed near the end. As wonderful in its own way as the version that was subsequently issued, this first take would eventually be released on the Beatles' Anthology 3 compilation album in 1996, underscoring the beauty of a song that George had written at his parents' home in Warrington, Cheshire.

"I was thinking about the Chinese I Ching, 'The Book of Changes',” he remarked in the 2000 Anthology book. "In the West we think of coincidence as being something that just happens — it just happens that I am sitting here and the wind is blowing my hair, and so on. But the Eastern concept is that whatever happens is all meant to be, and that there's no such thing as coincidence — every little item that's going down has a purpose. 'While My Guitar Gently Weeps' was a simple study based on that theory. I decided to write a song based on the first thing I saw upon opening any book — as it would be relative to that moment, at that time. I picked up a book at random, opened it, saw 'gently weeps', then laid the book down again and started the song.”

Still, George's vision of the number was altogether more grandiose than the aforementioned, starkly beautiful first take. So, three weeks later, on 16th August, 14 takes were recorded of an all-new rhythm track, with him playing electric guitar while Ringo drummed, Paul was on bass and John played the organ. (It's perhaps telling that, even though the track sheet for this session listed George Martin as the producer, one of the tape boxes bore the inscription 'The Beatles; Produced by the Beatles'.)

It was on 22nd August, while recording 'Back In The USSR', that Ringo quit the band, and his return on 4th September to film the 'Hey Jude' and 'Revolution' promotional videos was a day after 'While My Guitar Gently Weeps' had been transferred to eight-track and George Harrison had spent an entire evening attempting to make his instrument sob its heart out by performing backwards solos instead of resorting to the use of a wah-wah pedal. This would have entailed writing a short score for the solo, reversing that score and recording him playing the backwards melody note for note, before then reversing the tape so that the listener would hear the backwards — and hopefully weeping — guitar playing the regular melody.

Back To The Drawing Board

The result, unfortunately, didn't fulfil George's expectations. So, on 5th September, after welcoming Ringo back to EMI by decorating his drum kit and Studio Two with flowers ("He'd be the only one who would think of doing something like that,” says Ken Scott) Harrison began work anew.

On that day, he initially recorded two vocals and made another pass at the lead guitar while maracas and extra drums were overdubbed onto the eight-track. Again, George was dissatisfied. So, scrapping all previous work on the song, he and his fellow Beatles then set about recording yet another remake; this time without George's backwards solo but with his acoustic guitar and more prominent guide vocal, as well as John's electric guitar (played on his Epiphone Casino), Ringo's drums and Paul's piano. John overdubbed the organ.

"For Ringo's kit, I probably used a KM56 on the snare, [AKG] D20 on the bass drum, [AKG] D19s on the toms and an STC 4038 overhead,” Ken Scott says. "We were varying things back then, but that was a fairly standard setup. At EMI, those of us who had just become engineers always started off using the same techniques as those who had come before us. So, during the Magical Mystery Tour project I would have been copying Geoff Emerick precisely, but then I would have started experimenting. After all, working with the Beatles meant you had time to experiment and to learn things like what mics to choose because they were all up for experimenting. So, for the White Album I may have copied what Geoff did, but it also may have varied slightly.

"I remember Paul and I would go into the mic storage room and he would find a mic that he thought would look good and we'd have to use it. 'Oh, I like the look of that one. Let's try it.' It was a case of putting different mics in different places. Like on the piano, we'd do everything from putting the mic above it to underneath it, and probably try placing it up the pianist's arse at some point.

"In addition to Paul's bass being DI'd, the cabinet probably would have been miked with a 4038, [Neumann] U67 or [AKG] C12. I would have used two 4038s on the organ, 67s on John and George's guitars, and it could have been anything on George's vocal.”

Take 25

The group reeled off no fewer than 28 new takes of 'While My Guitar Gently Weeps', of which the 25th was deemed the best. However, Harrison was still far from happy.

"We tried to record it,” he explained in the Anthology book, "but John and Paul were so used to just cranking out their tunes that it was very difficult at times to get serious and record one of mine. It wasn't happening. They weren't taking it seriously... so I went home that night thinking, 'Well, that's a shame,' because I knew the song was pretty good. The next day I was driving into London with Eric Clapton, and I said, 'What are you doing today? Why don't you come to the studio and play on this song for me?' He said, 'Oh, no — I can't do that. Nobody's ever played on a Beatles record and the others wouldn't like it.'

"I said, 'Look, it's my song and I'd like you to play on it.' So, he came in. I said, 'Eric's going to play on this one,' and it was good because that then made everyone act better. Paul got on the piano and played a nice intro and they all took it more seriously. (It was a similar situation when Billy Preston came later to play on Let It Be and everybody was arguing. Just bringing a stranger in amongst us made everybody cool out.)”

With Eric Clapton's magnificent, blistering, blues-rock solo in the can (performed on the solid red Gibson Les Paul that he had given to George Harrison at the beginning of August), 'While My Guitar Gently Weeps' was completed with overdubs of Paul McCartney's bass, some Ringo Starr percussion, George's addition of a few high-pitched organ notes and, along with his lead vocal, backing harmonies contributed by Paul.

"It'd been a few years since I'd seen them and they had changed,” Clapton recalled in Martin Scorsese's 2011 George Harrison documentary Living In The Material World. "This particular song was a strong view and it was coming very much from where George had found himself as a result of becoming involved with mysticism. Seeing John and George and Paul sing together when they were doing harmonies and things... it was fantastic.”

"We'd had guest instrumentalists before,” Paul McCartney stated in the Anthology book. "Brian Jones had played some crazy stuff on sax [for 'You Know My Name (Look Up The Number)'] and we'd used a flute and other instruments — but we'd never actually had someone other than George (or occasionally John or me) playing the guitar. Eric showed up and he was very nice, very accommodating and humble and a good player. He got wound up and we all did it. It was good fun actually. His style fitted very well with the song and I think George was keen to have him play it — which was nice of George because he could have played it himself and then it would have been him on the big hit.”

Clapton In Disguise

All that Clapton really wanted was to blend in, which is why Ken Scott and second engineer John Smith now recall next to nothing about the historic session.

"Eric didn't want his guitar to sound like an Eric guitar,” Scott says. "He wanted it to sound like a Beatles guitar. So, the way we dealt with that was to ADT and flange it during the mix. It's not as if we always did that with George's guitar, but we did do it with everything and everyone at some point or another.”

Artificial Double Tracking was one of numerous tools invented by Abbey Road's ever-creative technical team during the 1960s, and so was the flanging, achieved by way of a bored Chris Thomas waggling an oscillator back and forth to vary the speed of a four-track tape. This was because Clapton's solo had been recorded with the Studer, since ADT and flanging still couldn't be employed on the 3M eight-track.

"One of the great things about the Studer four-tracks was that they were the only machines to have individual playback and sync amps,” Scott continues. "This meant you could take off the sync head at the same time as you were taking off the playback head, which was essential to doing ADT, and we couldn't do that on the 3Ms until, eventually, Abbey Road got an extra playback card and wired it up so that it could be plugged in anywhere we wanted to do ADT. This wasn't available to us for the White Album, so Chris flanged the organ and Eric's guitar on 'While My Guitar Gently Weeps' before we bounced the four-track across to the eight-track.”

On 7th October, 1968, Ken Scott made mono mixes of the 'While My Guitar Gently Weeps' backing track that had been recorded on 5th September, and he did so again on 14th October when he also took care of the then-still-less important stereo mix.

"None of the mixes were ever that hard back then,” Scott says. "Any changes were made as we were going along, so we didn't need to make drastic EQ changes every couple of bars. They would have been done while we were recording. In fact, before we began mixing tracks on the White Album, the Beatles got into the habit of saying, 'OK, we want full bass and full treble on everything'. So, we'd just turn the EQ full up on every track. The desk EQ was at 5k and 100Hz, and if you were to put a full 5k boost and full low-end boost on one of today's modern desks it would be unbearable. Back then, however, we could do it on every track and they still sounded good, which just goes to show how smooth the EQ was on those boards and how little of it we had to play with. Unlike today, we had to get the sound in the studio to start with.”

Chance Of A Lifetime

"Recording the Beatles was a wonderful experience, but while there were times when their creative juices were flowing and it was incredibly exciting, there were others when it was as boring as hell. For instance, I remember it took three days just to get the basic track of 'Sexy Sadie'. Primarily, they were down in the studio, figuring out the different parts, and all we had to do was make sure the tape was constantly running. What got me through those times was the firm belief that, in the end, it would turn into something amazing, and generally that was the case. But then, I didn't have to work on 'Revolution 9'.

"Here I was, at the age of 21, working with the greatest band in the world. How could it not be exciting for me? To my mind, one of the most brilliant things about the Beatles was their ability to make decisions on the fly. There could be a mistake somewhere along the line and instantaneously we'd hear, 'Hang on, I like that, let's keep it.' I witnessed that several times and their instincts were flawless. They didn't have any rules because they weren't technically trained. They just did what sounded good to them and what felt right to them and they came up with absolutely incredible things, even when a lot of it was by accident. Many of their musical ideas and technical demands caused difficulties for us in the control room, but they'd push us to sort those things out and I'm so glad they did.”

Birthday Party

Although the White Album-era Beatles were now spending months rather than days in Abbey Road, they were still capable of working fast on occasion. A case in point was the McCartney rocker 'Birthday', which was written and recorded in a single day.

"Paul was the first to arrive in the studio,” Ken Scott recalls. "He began playing the riff on the piano and he'd basically composed the song by the time the other guys arrived, at which point he taught it to them while I worked on the sound. This was during the time when George Martin was on holiday, so Chris Thomas was producing and, thanks to him mentioning that the classic rock & roll movie The Girl Can't Help It was going to be on TV that night, it was decided that we'd all take a break and go around the corner to watch it at Paul's house. That's what we did once they'd already laid down the backing track to 'Birthday', and when we returned to the studio — perhaps because the movie inspired everyone — the pace really picked up and we overdubbed the piano, hand claps, tambourine and lead vocals, as well as the backing vocals by Yoko and [George's wife] Pattie.”

Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust

Abbey Road To Ziggy Stardust: Off-The-Record With The Beatles, Bowie, Elton & So Much More (Alfred Music Publishing), is Ken Scott's new memoir. Co-authored with Bobby Owsinski, it documents a career that, in addition to the aforementioned artists, has also seen him produce and/or engineer anyone from Pink Floyd, Procol Harum, Jeff Beck and the Rolling Stones to Lou Reed, Harry Nilsson, the Tubes, Devo, Kansas and Supertramp.

"I've tried to keep the technical side of things to a minimum,” says Scott who, after relocating from EMI Studios to Trident in 1969, made his production debut on Bowie's 1971 album Hunky Dory, moved to LA about six years later and has recently been involved with the development of Sonic Reality's Epik Drums software package, featuring the kits and grooves of Bill Cobham, Bob Siebenberg, Terry Bozzio, Woody Woodmansey and Rod Morgenstein.

"There obviously has to be a certain amount of that information,” he continues, "but it's more about eye-opening and entertaining stories. In the past, a couple of publishers approached me about writing my own book, but it quickly became clear they wanted the dirt more than anything else. I wasn't interested in that. My life has been amazing and 95 percent of it has been fun, so that's what I wanted to put across and fortunately Alfred Music Publishing shared my vision.

"In the book, I describe how certain songs came about, recall watching several of them being written and provide behind-the-scenes stories about what went on in the studio with many famous — and some not-so-famous — artists. It covers everything I've done. June 6th, when it comes out, happens to be the 50th anniversary of the Beatles first setting foot in Abbey Road for their recording test, as well as the 40th anniversary of the release of The Rise & Fall of Ziggy Stardust & The Spiders From Mars, which I co-produced with David Bowie. So, the timing is perfect and, while enjoying the book's many previously unpublished photos, I think readers will learn a lot from what I have to say.”