John Fry in the control room at the original Ardent Studios on National Street, where Big Star's #1 Record was begun, in a photo taken around 1969.Photo: Terry Manning

John Fry in the control room at the original Ardent Studios on National Street, where Big Star's #1 Record was begun, in a photo taken around 1969.Photo: Terry Manning

Three decades after they disappeared into obscurity, the cult of Big Star continues to grow. John Fry was the engineer and studio owner who oversaw the recording of their now-classic albums #1 Record and Radio City.

Though they never had a chart album or a hit single, and their original line-up played only a handful of gigs, Big Star's influence has been colossal. Their tightly crafted brand of harmony-led power-pop stood in stark contrast to other rock bands of the early '70s, and would later be rediscovered and championed by a whole generation of musicians, most notably REM. Comprising singer/songwriter/guitarists Alex Chilton and Chris Bell, together with bass player Andy Hummel and drummer Jody Stephens, the Memphis-based quartet undoubtedly summoned the spirit of the Beatles on their 1972 debut album, #1 Record.

Despite the album's excellence, however, the public didn't catch on, and marketing, promotion and distribution problems on the part of Stax didn't exactly help sales. Chris Bell, an Anglophile who was greatly influenced by the Fab Four and other bands of the 'British Invasion', was bitterly disappointed by the failure of #1 Record and also hindered by personal problems. Furthermore, whereas Alex Chilton, the former Box Tops vocalist on hits such as 'The Letter' and 'Cry Like A Baby', veered towards live performance, Bell wanted to spend more time in the studio. The result was that Bell parted ways with Big Star at the end of 1972, en route to a stalled solo career and his untimely death in a car crash at the age of just 27.

It was after Big Star had disbanded and reformed as a three-piece outfit that, in 1974, they reached their brief apotheosis with Radio City, an altogether more intense, raw and rough-edged album that contained the group's biggest hit-that-never-was, the much-covered 'September Gurls'. Big Star's subsequent output — a live set and third studio album — never scaled the heights of either #1 Record or Radio City, which featured one last contribution from Chris Bell on the anthemic 'Back Of A Car'.

Starting Out

Bell, who first collaborated with Andy Hummel and Jody Stephens in various high-school covers bands, had worked as a part-time engineer and session man at Ardent Studios in Memphis. It was there that he met Alex Chilton, where Big Star later recorded, and where John Fry's Ardent record label was based.

Fry had launched the label during his early teens in the late 1950s, while operating a studio out of a converted garage in his parents' home. Fascinated by technology, especially the radio, he indulged his love of music by recording commercials for an Arkansas radio station that he helped build and programme with friend John King, while also releasing the efforts of local school and college bands that were tracked on his 10-input Altec 250 SU valve console and Ampex 354 two-track tape machine. Another Ampex was used for overdubbing.

"We had sync on the two-track machine, so you could play one track and theoretically overdub on the other," says Fry. "However, you couldn't do that too many times. We only had a few basic devices, but I've still got the Pultec EQP1A equaliser that I had in the garage back then, and it still works."

When his parents decided to move home in 1966, Fry was motivated to find commercial premises, and so it was that Ardent relocated to a brand-new building on National Street. Comprising about 2000 square feet of open space, this accommodated a large recording area once the walls and partitions had been constructed, along with a control room that housed a state-of-the-art Scully four-track machine and an Auditronics console that incorporated Spectrasonics amps and equalisers. (Auditronics was owned by one Welton Jetton, whom Fry describes as "a great friend and mentor".)

'Sitting in the back of a car...': the three-piece Big Star line-up credited on Radio City featured (from left) Andy Hummel, Jody Stephens and Alex Chilton.Photo: John Fry

'Sitting in the back of a car...': the three-piece Big Star line-up credited on Radio City featured (from left) Andy Hummel, Jody Stephens and Alex Chilton.Photo: John Fry

"I was 21 years old, I looked like I was about 16, and Stax started sending us all of their outside work because they couldn't cope and we had the kind of equipment that they were familiar with," Fry recalls. "So, all of a sudden, I was catapulted from the garage to doing work with real successful artists who were going to sell and be heard on the radio. I still look back on that time and, for the life of me, I don't know why they trusted this kid to work on their stuff. Terry Manning was in the middle of all this — he'd been in a couple of bands who'd recorded in the garage studio, and he'd been recording others, too — and when Ardent started up on National Street in '66 he was the only other engineer besides myself. Between the two of us, we did everything, and a lot of times that meant working close to around the clock; one of us working in the daytime and the other working at night.

"Until Stax closed in 1975, the association was so close it was almost like Ardent was a branch of that company. They had no ownership interest, but their people were in and out of our studio constantly. That was a wonderful experience to be around, with really, really great musicians, and I also had Jim Dickinson by my side, who had been producing stuff since the garage studio days. He was the producer in residence, handling a lot of the local bands who we were still recording, and our working relationship has now lasted about 45 years."

Although Ardent is now a partnership venture, John Fry owned it outright through the years when the studio hosted projects by, among others, Led Zeppelin, Leon Russell, Sam & Dave, Isaac Hayes, the Box Tops and Booker T & the MGs, as well as when it relocated to an even larger, purpose-built facility on Madison Avenue in November 1971. This has attracted the likes of Lynyrd Skynyrd, REM, the White Stripes, the Gin Blossoms, the Replacements, Robert Cray, Waylon Jennings, Bob Dylan, BB King, George Thorogood, the Staple Singers and ZZ Top.

"When Big Star recorded here, the studio layout was still the 1966 configuration, with a largely rectangular room," Fry explains. "However, while we had four-track in '66, by '68 we had eight-track and by the following year we were using 16-track. #1 Record was started on National Street and finished in the new facility on Madison, and by then we had replaced the smaller Spectrasonics/Auditronics console with a larger, 24-input, eight-buss one, we had a 3M 16-track recorder, for monitoring we were using JBL 4350s, and in terms of reverb we had three EMT 140 stereo plates."

The Benefits Of Dolby

John Fry is relatively unusual among engineers in having fond memories of the noise-reduction systems that were around in the early '70s. "We'd bought our first Dolby noise-reduction system because Led Zeppelin had required it when Terry [Manning] was mixing the Led Zeppelin III album, and this consisted of the huge old A301s — two channels of it was as big as a bread box. We really loved having that technology, and when we got the 16-track we then got the Dolby A361s. So, we had Dolby A for multitrack and two-track, and unless someone requested otherwise, we by and large used it for everything we could.

"A lot of people back then had misgivings — they'd say 'Oh, it colours the sound, it changes the sound,' but my experience was that the people who had trouble with it were the ones who did not know how to align their tape machines to begin with. The system was demanding. It wanted the exact same level that went through it on record to come back to it on playback, but if you aligned the Dolby systems properly and you aligned your tape machines so that they had a reasonably flat frequency response, it was a tool that I never wanted to do without. The difference that it would make was incredible. I mean, just listen to some of those Big Star things — we could not have done them without the ability to maintain a good signal-to-noise ratio."

A Relaxed Atmosphere

The approach at Ardent was fairly easy-going; people couldn't just walk in off the street, but if the studio was available late at night, musicians who were regulars there would often be allowed to go in and work on ideas. This in turn meant that several of these musicians learned to engineer for themselves, and the result was that while John Fry would, for example, record the basic tracks on the Big Star sessions and handle some of the overdubs, at other times he would leave the band members to their own devices before then taking care of the mix.

The control room in Ardent Studio A on Madison Avenue was based around a Spectrasonics console.Photo: Terry Manning"When Chris Bell was still in the band, he probably took more interest than anybody in the production and technology end of things," Fry remarks. "He had a good production mind and he was always wanting to try or come up with things. So, although Big Star 3 was produced by Jim Dickinson, #1 Record was really produced by the band, and so was Radio City.

The control room in Ardent Studio A on Madison Avenue was based around a Spectrasonics console.Photo: Terry Manning"When Chris Bell was still in the band, he probably took more interest than anybody in the production and technology end of things," Fry remarks. "He had a good production mind and he was always wanting to try or come up with things. So, although Big Star 3 was produced by Jim Dickinson, #1 Record was really produced by the band, and so was Radio City.

"When Chris quit the band in December 1972, he and Alex had already started writing songs for the second album. For his solo projects he had songs that he wanted to take 100 percent of, so he and the other guys made a deal among themselves whereby Big Star took some of the songs and Chris took others. Unfortunately, that means several of the songs on Radio City should credit him as a writer, but that wasn't the arrangement."

Instead, of the album's 12 tracks, three (including 'Back Of A Car') are credited to Chilton and bass player Andy Hummell; one is credited to Chilton, Hummell and drummer Jody Stephens (who now manages Ardent Studios); another sees Chilton sharing the honours with percussionist Richard Rosebrough; one is written by Hummell; and the remaining half-dozen — including 'September Gurls' — are credited to just Alex Chilton.

"The reason why the second album is a little bit rougher, with fewer harmonies and so on, is partly due to the absence of Chris's influence in the studio," says Fry. "And then there's also the fact that some extra folks were playing on there — Richard Rosebrough played drums and percussion in places, and there were probably also other people on there whose names I don't recall. In general, we followed the same recording pattern as on the previous album, except that the band would now set up as a three-piece. They would do tracks and I would normally record them and then leave them to their own devices most of the time when it came to the overdubs. The exceptions are a few tracks which Richard Rosebrough recorded from the get-go, including 'She's A Mover' and 'Mod Lang'.

"Another reason for the change in sound, to my mind, and without getting too metaphysical about it, was the relocation of Ardent Studios. This actually took place during the recording of #1 Record, and we moved from a part of the city where there was not much of anything going on to an area called Midtown which was becoming the first sort of entertainment area in Memphis. This city didn't pass a law allowing the sale of liquor in restaurants and clubs until the early 1970s, and a lot of the new bars and clubs that opened were in Midtown, right down the street from our studio. All of a sudden, bands were playing in these places, there was a lot going on, and some of the things that ended up on Radio City were probably the result of people spending a little time partying before coming in to record.

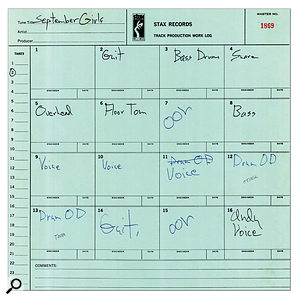

The track sheet and mastering notes for 'September Gurls'.Photo: John Fry"The songs tended to be recorded piecemeal. When somebody had written a song, or maybe there were two songs or three songs, we would track those and then they would proceed to overdub onto them. It was not the kind of process that you see more commonly today, where people say 'OK, we've got all the songs, we're going to cut all 12 tracks and then we're going to do all the overdubs before we do all the mixing.' It was a little more fragmented, and usually the guys would record as soon as they wrote. I don't recall songs sitting on the shelf for a long time... 'September Gurls', I'm pretty sure, was the only song recorded in that particular session."

The track sheet and mastering notes for 'September Gurls'.Photo: John Fry"The songs tended to be recorded piecemeal. When somebody had written a song, or maybe there were two songs or three songs, we would track those and then they would proceed to overdub onto them. It was not the kind of process that you see more commonly today, where people say 'OK, we've got all the songs, we're going to cut all 12 tracks and then we're going to do all the overdubs before we do all the mixing.' It was a little more fragmented, and usually the guys would record as soon as they wrote. I don't recall songs sitting on the shelf for a long time... 'September Gurls', I'm pretty sure, was the only song recorded in that particular session."

Simple But Effective

Although there were occasional variations, the general setup comprised Alex Chilton, Andy Hummel and Jody Stephens recorded live together on the studio floor. "We had isolation booths, and occasionally we'd stick a guitar amplifier in one of them to try to keep it out of the drums, but a lot of times the studio space itself was large enough to achieve that," Fry says. "We also had a sort of bass trap into which we could face the bass amplifier so that it didn't just go everywhere. A lot of the bass was recorded direct — occasionally, there'd be a direct track and an amp track, but it was the direct that usually ended up getting used.

"At the same time, the typical drum setup used a lot fewer microphones than anybody would be using today. There were four tracks of drums on 'September Gurls' — the bass drum, the snare, an overhead and a floor tom-tom track — plus there was also a tom-tom overdub track, and when you listen it's obvious what that is. It's a big, booming sound that you hear periodically.

"The bass drum was usually miked with a dynamic microphone, often an [Electrovoice] RE20, and sometimes Jody would have the front head off or have one with a hole in it. The single snare-drum microphone was usually a Neumann KM84, and I'd be careful to turn the pad on, while the overhead mic would vary a little bit but often be a [Neumann] M249 or occasionally some other condenser microphone like the [Neumann] U67 or U87. I sometimes also used a U67 or U87 for the tom-tom, and that would be about it.

The original four-piece line-up of Big Star (with Chris Bell, second from left) in Alex Chilton's living room, 1971. Photo: John Fry"If we were recording an amp track for the bass, Andy normally played his Fender Precision into a Hiwatt amplifier. And while Alex had a great variety of guitars and changed among them, he would often use either a Fender Super Reverb or a Hiwatt, miked with a small-diaphragm condenser mic like a KM84 — again being careful to turn on the pad — and sometimes with a dynamic like the trusty [Shure SM] 57 or the RE20. That's when I was taking care of the recording. I have no idea what was used when the sessions took place at 3am, but they sound all right. On this record, either Richard Rosebrough or Andy Hummel would be responsible for that. Richard was working as an engineer full-time at the studio in addition to playing drums on a lot of the records, and Andy had become a pretty good engineer himself, certainly competent enough to do overdubs well and not mess them up.

The original four-piece line-up of Big Star (with Chris Bell, second from left) in Alex Chilton's living room, 1971. Photo: John Fry"If we were recording an amp track for the bass, Andy normally played his Fender Precision into a Hiwatt amplifier. And while Alex had a great variety of guitars and changed among them, he would often use either a Fender Super Reverb or a Hiwatt, miked with a small-diaphragm condenser mic like a KM84 — again being careful to turn on the pad — and sometimes with a dynamic like the trusty [Shure SM] 57 or the RE20. That's when I was taking care of the recording. I have no idea what was used when the sessions took place at 3am, but they sound all right. On this record, either Richard Rosebrough or Andy Hummel would be responsible for that. Richard was working as an engineer full-time at the studio in addition to playing drums on a lot of the records, and Andy had become a pretty good engineer himself, certainly competent enough to do overdubs well and not mess them up.

"With the rhythm track, we would try to get a good take all the way through, and there was not much editing involving the multitracks. The place where there was more frequent editing was on the stereo mixes. Of course, having no automation other than getting extra sets of hands to come in, a lot of times if we had a big change from one section to another and couldn't make all the moves the way we wanted to, we would just simply do it by making an edit. I think 'You Get What You Deserve' and 'Daisy Glaze' were done that way."

Hidden Guitars

All in all, the recording process, which would often also include an unrecorded vocal mic for foldback into the headphones, was amazingly simple. Indeed, the track sheet for 'September Gurls' lists the aforementioned bass drum, snare, overhead and floor tom, along with a percussion track, two guitar tracks, a pair of tracks for backing vocals and three lead vocal tracks.

During the recording of #1 Record, Ardent Studios moved to new premises on Madison Avenue. This was the live room in Studio A.Photo: Terry Manning"I can't believe that we used all three of those vocal tracks," says John Fry. "I'm sure a choice was made and two ended up being used. And I'm also sure, despite it not being marked on the track chart, that an additional guitar was just stuck into the space on of the other tracks. When you listen to the recording, I don't know what the main electric guitar was, but Alex had a Rickenbacker 12-string, and you can hear that pretty clearly, and then the real high guitar harmony that you can hear from time to time was played on a fascinating little instrument made by Fender, called a Mando-guitar — kind of like a mandolin and it worked sort of like a mandolin. I don't know if the product was successful or if very many were sold, but Alex was the only person I knew who owned one... I'd love to have one now."

During the recording of #1 Record, Ardent Studios moved to new premises on Madison Avenue. This was the live room in Studio A.Photo: Terry Manning"I can't believe that we used all three of those vocal tracks," says John Fry. "I'm sure a choice was made and two ended up being used. And I'm also sure, despite it not being marked on the track chart, that an additional guitar was just stuck into the space on of the other tracks. When you listen to the recording, I don't know what the main electric guitar was, but Alex had a Rickenbacker 12-string, and you can hear that pretty clearly, and then the real high guitar harmony that you can hear from time to time was played on a fascinating little instrument made by Fender, called a Mando-guitar — kind of like a mandolin and it worked sort of like a mandolin. I don't know if the product was successful or if very many were sold, but Alex was the only person I knew who owned one... I'd love to have one now."

Again, when it came to tracking the vocals, since some of these were recorded in the wee small hours, John Fry wasn't always the man pushing the faders. "One thing about training a lot of engineers in-house is that they tend to do whatever you do," he says. "They do what they've seen you do, and so in this case, regardless of whether or not I was engineering the session, the vocals probably would have been recorded with a tube M249. Otherwise, it would have been a U67 or U87. However, if an M249 was available, I always enjoyed using it."

Cutting Remarks

By the time that Big Star's records were made, Stax had aquired its own mastering department, and had invested in a Neumann VMS70 lathe and Neumann cutting system. This cost around $125,000 back in the early 1970s.

"We would go over there and work on all our stuff with a mastering engineer named Larry Nix," Fry remembers. "Larry and his son Kevin still run L. Nix and Company Mastering inside our building, where they master our Ardent Records releases today. Anyway, I was very hands-on with that back then. I wouldn't just hand it to somebody, but pretty well sit there and run them crazy, and I know Terry [Manning] was a stickler, too, because a lot of things that you don't have to worry about today had to be taken into consideration when you were mixing for something that you knew was going to be released on a vinyl record.

"The SX74 cutter head was cooled with helium gas, and I would turn the helium flow up to the max to get a little higher level without tripping the cutter-head circuit breakers that were there to protect a $9,000 device from people like me. There were lots of obstacles and problems that you had to deal with that no longer exist today, and we even went so far as to make a little setup where, before we let a master go out, we'd bring back the reference acetate and see if we had achieved the result that we wanted.

"We built an A-B switching system where we could hook up a turntable and play the reference acetate and A-B it against the master tape to see if it was different, and if so, in what way it was different. I mean, was it different in a better way that we were trying to make it by using equalisation and compression in mastering, or did we mess it up or was there something wrong? One of the most shocking things to me when I first started doing that was when I discovered the whole phenomenon of diameter loss. The circumference of a 12-inch record is much larger at the outside than it is at the last band, and since the turntable is rotating at a constant speed the groove velocity, the relative velocity of the disc, to the cutting stylus or the playback stylus at the outside is much faster than it is on the inside band. It's like having a tape recorder that starts out at 30ips and, over the course of the recording you're making, very gradually slows down to seven-and-a-half.

"One thing I'll say about the Neumann system is it was a beautiful thing. It still is. That thing is still here. You could A-B between that reference acetate and the master tape, get them running by hand in synchronisation, and basically at the outer bands you couldn't hear any difference. However, if you didn't use some kind of compensation or diameter equalisation, the reference acetate played back with a lot of high-frequency roll-off by the time you were into the fourth or fifth or sixth cut, and that was always a real source of annoyance to me. You needed to use compensating equalisation to boost the high frequencies and counter the diameter-loss effect, but if you did, your inner groove distortion would increase markedly. So, there was this trade-off that you had to make, and that was always very frustrating to me. Most people who listened to the records were completely unaware of diameter loss because it occurred so slowly, and they didn't have the master tape to A-B it to. But boy, if you'd A-B it, it'd make you neurotic.

"#1 Record and Radio City were recently released on hybrid Super Audio CD. George Horn, the mastering engineer at Fantasy, worked from the original stereo analogue mixes and he did what I think is an excellent job of presenting the albums without some of the compromises we made in mastering for vinyl. Fans should buy this version even if they only have access to a standard CD player. It's markedly better than the previous reissues. However, they should also buy it quickly since I don't know how long it'll remain in print, given the level of support for SACD."

Mixing Reverbs

At the time of the Radio City sessions, Ardent actually had two studios up and running inside the Madison Avenue complex. The second one also had a Spectrasonics console built by Auditronics, and this was the desk on which the album was mixed at the rate of about one song per day. "That board was very similar to the one we had on National Street, although with three-band equalisation instead of two-band equalisation," Fry recalls. "The other things we acquired when we moved over here were three live echo chambers to add to our three EMT plates. Normally, when I was mixing — and I wouldn't have this for every echo source — I would have at least one of the echo sources pre-delayed, again using a tape recorder to do that because there were no delay lines. I would run the echo through a two-track Scully machine, usually running at 30ips so that the delay wasn't all that big. Somebody will probably criticise my math, but I think that gave us a 30-millisecond pre-delay.

Jody Stephens (left) and John Fry today.Photo: John Fry"The way that I would normally configure the EMTs to have them available — and I wouldn't always use all of this — was to have one set very short. The EMT 140 had that thing that looked like a big wheel on top of it, where you could adjust the damping on the plate and also adjust the reverb time, and I'd have one set very short, one set medium and one set somewhat longer. Well, we frequently set up our chambers that way, too — we would have one with no absorptive material in it at all; we would have one that we'd thrown a few blocks of fibreglass into, so it was kind of a medium; and then we would always try to have one that was very short. I really didn't perceive it as reverberation as much as I perceived it as almost a loudness enhancement. I always enjoyed having all of these echo sources, and if I thought it was appropriate I would use as many as three or four different ones on various instruments for any one song.

Jody Stephens (left) and John Fry today.Photo: John Fry"The way that I would normally configure the EMTs to have them available — and I wouldn't always use all of this — was to have one set very short. The EMT 140 had that thing that looked like a big wheel on top of it, where you could adjust the damping on the plate and also adjust the reverb time, and I'd have one set very short, one set medium and one set somewhat longer. Well, we frequently set up our chambers that way, too — we would have one with no absorptive material in it at all; we would have one that we'd thrown a few blocks of fibreglass into, so it was kind of a medium; and then we would always try to have one that was very short. I really didn't perceive it as reverberation as much as I perceived it as almost a loudness enhancement. I always enjoyed having all of these echo sources, and if I thought it was appropriate I would use as many as three or four different ones on various instruments for any one song.

"In terms of other equipment, my compressor of choice — and we still have two of these beautiful things, one of the most underrated pieces of equipment that I think ever existed — was the Universal Audio 176. Not the 1176, but the valve one, the 176. If those guys at UA are going to bring out reproductions of their own equipment, I don't know why they don't start making that again. It was effective, it was warm-sounding — although it didn't unduly colour the sound — and it had variable ratio, and if you set it on a low ratio you could really use a tremendous amount of gain reduction without it being all that apparent.

Alex Chilton in the control room at Studio A, Madison Avenue, circa 1973.Photo: John Fry

Alex Chilton in the control room at Studio A, Madison Avenue, circa 1973.Photo: John Fry

"The F700 buss compressor that I used back then was made by Audio Design & Recording, the English company that later changed its name to ADR, and it was a little modular system. There was a little rack, and each module was maybe four inches wide, six inches high and you could stereo link to it. I would always use that as the stereo buss compressor, and we still have it today, it still works and we use it regularly along with considerably more modern items."

Gurls Aloud

While the Radio City album was originally mastered on December 3, 1973, the 'September Gurls' single was mastered more than seven months later, on July 26, 1974, and John Fry was among the people who had high expectations for the song. "I loved it," he says. "It was just two minutes and 41 seconds long — can you believe that? — and I said to myself 'This is really going to work for radio.' To me, it still holds up today and I still enjoy listening to it — among a lot of other things, we [Ardent Studios] have it on our music-on-hold on the phone and it sounds pretty good on there. However, if somebody had told me in 1973 or 1974 that anybody was going to be interested in this more than 30 years later, I would have just said 'You're crazy. That's never going to happen.'

"A few years went by and I thought nobody knew anything about this music, but then all of a sudden in the late '70s there was all this interest and a call for it to be reissued, for the shelved third album to be issued, and after that it took on a life of its own and it's still going on today. All of which goes to show that you can be right in the middle of something special and, more often than not, you don't realise it until later."

In September 2005, Big Star, now comprising Alex Chilton and Jody Stephens together with John Auer and Ken Stringfellow of the Posies, released a new studio album, In Space, recorded at Ardent and issued on the Rykodisc label. This is the band line-up that has been performing since 1993, yet while reviews have been solid, most have been quick to point out that Radio City it isn't. And how could it be? How can anything match a cult classic? As Ryan Adams recently stated "Big Star makes me want to kill myself. Or get high and fuck. On a grassy hill in the South with the sun out in the Fall."

Who can argue with that?