Joan Jett's heartfelt reworking of the Arrows' 'I Love Rock & Roll' became an international hit and turned her career around. Glen Kolotkin tells us how it happened.

Joan Jett on stage at the Hammersmith Apollo, 1982.Photo: Sony Music Archive/Getty Images

Joan Jett on stage at the Hammersmith Apollo, 1982.Photo: Sony Music Archive/Getty Images

In the autumn of 1981, 23‑year‑old Joan Jett was already something of a rock & roll veteran. A native of Philadelphia who had relocated with her family to Los Angeles at the age of 12, the former Joan Marie Larkin had co‑founded the all‑girl power pop trio the Runaways in late 1975. This outfit quickly evolved into a quintet, signed with Mercury Records and released an eponymous debut album, after which Jett and her colleagues had toured the US and headlined shows with support acts that included Cheap Trick, Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers, the Ramones and Van Halen. A world tour had followed shortly after, by which time the Runaways had become part of the punk scene on both sides of the Atlantic. Yet despite a solid following in Europe and massive popularity in Japan, the band had never enjoyed major success in their home country, and following the Runaways dissolution in 1979, Jett pursued a solo career.

The Blackhearts

Glen Kolotkin in Studio B of Columbia's San Francisco facility, late 1970s.

Glen Kolotkin in Studio B of Columbia's San Francisco facility, late 1970s.

That same year, while in England, Joan Jett recorded three numbers with Sex Pistols Paul Cook and Steve Jones, and one of these just happened to be a cover of a song by a group called the Arrows which she had seen them perform on their self‑titled ITV pop show. Written by Arrows lead singer Alan Merrill and guitarist Jake Hooker, the song was 'I Love Rock & Roll', and, as Merrill later explained, it had been their "knee‑jerk response to the Rolling Stones' 'It's Only Rock & Roll',” which they viewed as Mick Jagger's "apology to those jet‑set princes and princesses that he was hanging around with.”

Be that as it may, the song was basically about a guy picking up a girl and taking her home, which was more than could be said for the Arrows' recording that, produced by Mickey Most and released as a B‑side on his RAK Records label, didn't find its way into many homes at all. Jett's punkish version had her making all the right moves to land a young guy for the night — "Said I can take you home where we can be alone / And next we were movin' on / He was with me, yeah me” — yet it, too, didn't do much for her career at a time when she couldn't land a record deal, and it would remain unreleased until its inclusion on Flashback, her 1993 compilation of out-takes and rare cuts.

The studio session with Cook and Jones had been financed by one Kenny Laguna, and as Jett's manager and co‑producer he would play an integral role in attaining mainstream success for both her and the song that she loved. A composer and producer, Laguna had first teamed up with Jett when writing material for We're All Crazee Now, a film based on the Runaways' career, and not only had he assumed the production reins when they entered the Who's Ramport Studios to record her own eponymous debut album, but the two of them had even released it on their specially formed Blackheart Records label, after it had been rejected by all of the major companies.

That was in 1980, when Jett embarked on a European tour with her new backing band, the Blackhearts, comprising guitarist Eric Ambel, drummer Danny 'Furious' O'Brien and bass player Gary Ryan. O'Brien remained in England when the others returned to the States and was replaced by Lee Crystal for a US tour, while Jett and Laguna had continued to independently distribute her album. Demand was such that Casablanca Records founder Neil Bogart had subsequently come on board, signing her to his new Boardwalk Records label, reissuing Joan Jett under the somewhat more tantalising title of Bad Reputation and funding sessions for a follow‑up album at Soundworks Recording in New York.

Glen Kolotkin

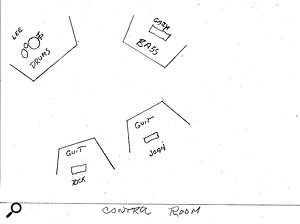

The live room set‑up for the recording of 'I Love Rock & Roll'.

The live room set‑up for the recording of 'I Love Rock & Roll'.

Co‑produced by Kenny Laguna and songwriter Ritchie Cordell (who had penned late‑'60s hits such as 'Mony Mony' and 'I Think We're Alone Now' for Tommy James & the Shondells), these sessions switched location to Kingdom Sound, a 24‑track studio in Long Island, at around the same time that Ricky Byrd replaced Eric Ambel as the Blackhearts' lead guitarist. Joining Laguna and Cordell behind the Harrison console was Glen Kolotkin, who had first met Laguna when the two of them were producing for the Berserkley Records label in San Francisco several years earlier.

The producer and/or engineer of acts ranging from Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, the Ramones, Moby Grape and Captain Beefheart to Barbra Streisand, Gladys Knight, Pete Seeger and Carlos Santana, Kolotkin was born in Philadelphia and raised on Long Island, New York. He first began engineering during the late '50s, using a 78rpm disc-cutting machine to record vocal groups. Thereafter, a stint running a radio station in the US Army was followed in 1965 by a job as a fully‑fledged engineer at A1 Sound, the first company that he saw when leafing his way through the 'Recording Studios' section of the Manhattan Yellow Pages.

A four‑track facility that had once been owned by Atlantic Records, prior to Herb Abramson assuming the reins from former partner Ahmet Ertegun, A1 provided Kolotkin with the opportunity to engineer sessions featuring the Four Tops, the McCoys and even Screamin' Jay Hawkins. A move to the Nola Penthouse Recording Studios on West 57th Street then saw him taking on the rock assignments for an owner who was preoccupied with jazz. Next up was the Columbia Records facility, where Kolotkin did remixes on both the Stones' Their Satanic Majesties Request and Hendrix's Electric Ladyland. In 1970, he relocated to Los Angeles and worked on records by Streisand, Taj Mahal, the Byrds and Janis Joplin.

Having recorded the songs 'Move Over', 'Cry Baby' and 'My Baby' on Joplin's final album, Pearl, Kolotkin quickly moved yet again, this time to San Francisco, where Clive Davis asked him to be in‑house engineer at Columbia's new studio. It was there that Kolotkin commenced a working relationship with Carlos Santana that, to date, has seen him engineer nine of the renowned guitarist's albums, including 1999's 15‑times‑platinum Supernatural.Amongst its nine Grammy Awards, one was reserved for Glen as a contributor to this 'Album of the Year'.

When Clive Davis resigned from Columbia in 1978, so did Glen Kolotkin, in the process becoming a freelancer, and it was in this capacity that he became involved with the sessions for what would turn out to be the I Love Rock & Roll album.

Controlled Leakage

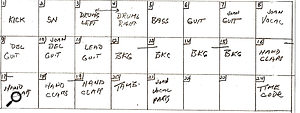

The track sheet for 'I love Rock & Roll'.

The track sheet for 'I love Rock & Roll'.

The Kingdom Sound control room contained a fully automated Harrison console, augmented by an MCI multitrack and Tannoy Big Red monitors. Looking through the window into the live room, Lee Crystal's drums were located in the far-left corner of the live area, next to Gary Ryan on bass, while Ricky Byrd and Joan Jett — one of only two women, along with Joni Mitchell, to have been named among Rolling Stone's 100 Greatest Guitarists of All Time — faced them, so that their guitar mics were pointing away from the screened‑off kit to minimise leakage.

"As long as the leakage isn't out of control I love it,” Kolotkin remarks. "I always used very directional microphones on the guitars, my favourite one being the [Electro‑Voice] RE20, which I also used with Carlos Santana. I remember when it came out I compared it with a [Neumann] U67 and the quality was very close. The RE20 may have been a little brighter sounding, but the isolation was much better, and so after that I'd use it whenever possible on vocals, bass drums and guitars. I'm pretty sure I used it on Joan's [Gibson Melody Maker] and on her vocals, because she was a real screamer and the RE20 had a built‑in pop filter. Other than that, I also used a Lexicon digital delay on her voice, along with a little reverb.

"With the bass drum, I usually removed the front head, put a pillow inside and aimed the mic towards the side of the drum. For the rest of the kit, there would usually have been Sennheiser 421s on the toms, a [Neumann] KM84 on the hi‑hat and a [Shure] SM57 on the snare, while for overheads I always used condenser mics, such as AKG 414s. There was a gate on the kick, as well as a parametric on the bass and snare drums.

"The bass was always DI'd — a lot of times we would use a mic on the amp but I'd never use that channel because it never sounded as good. On the guitar amps the RE20s were never aimed towards the middle of the speaker cone. They were always pointed towards the edge of the speaker and a few inches away from the screen to get a much fuller sound. Today, a lot of guys record one instrument at a time, but the musicians can't play off each other that way. That's why I always try to record basic tracks with the whole band. The feel is so much better, even when they get excited and may speed up a little at times.”

Getting Panicky

Glen Kolotkin today, at home in front of some of his many gold discs.

Glen Kolotkin today, at home in front of some of his many gold discs.

Not that Glen Kolotkin was particularly excited after recording commenced on the Joan Jett LP.

"The songs were pretty good, but nothing really struck me as a hit,” he says, while explaining why, when an additional track did offer definite chart potential, he then had good reason to feel a little insecure about his own position. "Towards the end of the sessions I was starting to get panicky, and so I kept asking Laguna and Cordell, 'What are we going to do for a hit?' At a meeting, Laguna told me Joan did have a song that she thought could be a hit, but Roy Thomas Baker wanted to produce it. Well, my ears definitely perked up when I heard his name. You see, several years earlier I had produced Journey's second album, Look Into The Future, but just when I thought I'd be producing them again Roy Thomas Baker had basically aced me out of the job. That album [Infinity] had turned out to be huge, and so as soon as I heard his name mentioned at the meeting with Laguna and Cordell, I moved fast.”

Kolotkin had Joan Jett and the Blackhearts play him the song. It was 'I Love Rock & Roll', and there and then, afraid of "being set up for another disaster involving Roy Thomas Baker,” he ensured they recorded it.

"They ran it down and I went 'Whoa!' because it was obviously a smash hit,” he recalls. "So, I said, 'Play it again,' while I pressed the 'record' button on the multitrack and they got it in the first take. Then I started to add parts and the tune was almost finished by the time that Ritchie Cordell and Kenny Laguna walked in. I told them, 'You've got to hear this! If this isn't a number one hit, I don't know what is!' This was at about 10 in the morning, when the session had been due to start, and we finished it by one in the afternoon.”

An Audience With The Blackhearts

The overdubs that were added included the doubling of guitar lines and the layering of backing vocals and hand claps on the chorus, enhanced by some EMT plate reverb and Lexicon reverb that ensured the recording was far heavier than the relatively tame Arrows track, and even that produced with the two ex‑Sex Pistols.

"It was my idea to have the backgrounds sound like an audience, because it was the perfect sing‑along record,” says Kolotkin. "We just had the group do about six layers of vocals on extra tracks, and I even sped up the machine a little for one layer to make it sound deeper and slowed it down for another layer to make it sound higher‑pitched. Then, we combined them down to two tracks because we only had 24 tracks to work with, did the same with the hand claps, and that made it sound like the whole audience was joining in. I'm sure that Kenny and Ritchie also contributed, along with the owners of the studio, because we wanted it to sound massive, and it didn't need to be perfect since an audience never usually sings in tune. All of them were standing around a couple of microphones, and we just kept building it up and up until the hair stood up on the back of my neck. That's when I knew it was right.

"Joan did her vocal in one or two takes, and that was it, all done by one in the afternoon. My entire goal was for it to sound live and for it to sound real, and I thought we achieved that until it came to the mix...”

At this point, Kolotkin's job title had been upgraded from engineer to also incorporate that of associate producer. "I couldn't keep my mouth shut,” he explains. "According to the deal we originally made, I was just getting an engineering fee, but I did contribute a lot to the album and especially to the main song, and so Kenny and Ritchie actually did me a favour by adding that credit.”

What's more, they also provided him with the leeway to keep working on the aforementioned track after the three of them had spent several hours producing six mixes that both Laguna and Cordell were perfectly happy with.

Real Sound

"To me, it didn't sound as exciting as when I'd first recorded it,” Kolotkin explains. "You know, everything was perfect — that's what you can do with automation — but I felt like we'd lost a lot of the energy. I thought it needed to be rougher and have more of an echoey sound, and so I said, 'Look, give me a few minutes with this thing. I just want to try it another way,' and they said, 'Go ahead.' I therefore pulled out all of the patches, took out the EQ, took out the automation, pulled the faders down to zero and did the track over.

"You see, when I mix alone I don't EQ individual instruments. I might zero in on one — working on the bass drum or snare drum a little — but what I'll basically do is get the best drum sound possible, add the bass, maybe brighten the bass a little if it needs that, and then add the guitars and make sure they fit, adding EQ to the whole band if necessary rather than do it separately. If you do it separately and put everything together, it's usually over‑EQ'ed. In this case, the remix took about 15 minutes, and then I called Ritchie and Kenny back in and said, 'What do you think? This is the way I really hear it.'

"It was totally different to the other mixes, and although I knew it wasn't perfect — at times I might have lost a little of the lead vocal because something covered it up — it didn't bother me to the point of wanting to redo it. I thought it had just the right feel and that it sounded live. When they're performing live, it's natural for singers to move away from the mic for a second, and at a concert you don't hear everything perfect. In fact, one of my complaints about what's happening today is that the artists don't even need to know how to sing. All they have to do is sing one verse and then you can copy and paste it, but to me all that stuff sounds sterile. When I was a kid, my friends and I used to sit around, playing records, and listen for things that weren't meant to be. Those mistakes made it real, and that was great. Today, there are so many things you can do, using equipment to change the pitch if something's slightly out of tune, and it's not real anymore.

"I wanted 'I Love Rock & Roll' to sound real, I wanted it to sound live, and when I played it to Ritchie and Kenny they did say they liked it. However, they also said they liked the other mixes we'd done during the past few hours, so then Kenny came up with the idea of putting the new mix in the middle of them, playing all of them for the band and letting them pick which one they wanted to use. I thought, 'That's fair enough,' and so I spliced the new mix into the middle of the others and as soon as the band members heard it they said, 'That's the one, that's the one!' And that was the one.”

Another Dime In The Jukebox?

At least as far as the musicians and producers were concerned, but not so a record company exec for whom the word 'anachronism' sprang to mind as soon as he heard a rowdy chorus of "I love rock & roll / So put another dime in the jukebox, baby / I love rock & roll / So come and take your time and dance with me.”

"After we finished the album, I had a meeting with Paul Atkinson at Columbia Records,” recalls Kolotkin, who is currently a partner with DJ Sandy Fagin and musician and producer Tom Harney in the Florida‑based Cool Music Company, which has a studio and a record label with country rocker Tom Jackson on its roster. "Paul had another band he wanted me to work with, and when he asked, 'Well, what have you been up to?' and I told him, 'I've just finished an album with Joan Jett,' he said, 'Oh yeah, we passed on her.' I said, 'Everyone passed on her, but I know we've got a hit here.' I actually had a cassette of the final mix of that song, so I played it for him and afterwards his only comment was, '"Put another dime in the jukebox, baby?” Aren't those lyrics dated?'”

True, there weren't many American jukeboxes that still charged a dime per play back in 1981. However, amending the line to "Put another quarter in the jukebox, baby” just wouldn't have worked as well, and besides, who cared? Certainly not Joan Jett's legion of new fans who, drawn to her classic trashy brand of loud, no‑frills, three‑chord rock & roll, with its strident beat and hard‑nosed guitars, helped place 'I Love Rock & Roll' atop the Billboard Hot 100 for seven weeks in the spring of 1982. They also sent it to the top spot in the UK, en route to a platinum certification and a number two placement in the Billboard 200 for the album of the same name. Boasting another chart hit in the form of Joan Jett's cover of 'Crimson & Clover', which Ritchie Cordell had also penned for Tommy James & the Shondells, the record has, to date, sold more than 10 million copies worldwide, yet it is the title track that still resonates for both performer and listeners alike.

"I think most people who love some kind of rock & roll can relate to it,” Jett remarked in a January 2008 Mojo magazine interview. "Everyone knows a song that just makes them feel amazing and want to jump up and down. I quickly realised this song is gonna follow you, so you're either gonna let it bother you or you gotta make peace with it and feel blessed that you were involved with something that touched so many people.”

Artist: Joan Jett & The Blackhearts

Track: 'I Love Rock & Roll'

Label: Boardwalk Records

Released: 1982

Producers: Ritchie Cordell, Kenny Laguna, Glen Kolotkin

Engineer: Glen Kolotkin

Studio: Kingdom Sound

Glen Kolotkin & Janis Joplin

Janis Joplin's final album, Pearl, was recorded at Columbia's Sunset Boulevard facility in LA between September 5th and October 1st, 1970, just three days before her death, and was released the following February, despite some tracks not having been fully completed. Paul Rothchild was the producer, and although Glen Kolotkin engineered just three of the songs — 'Move Over', 'Cry Baby' and 'My Baby' — before accepting another assignment, he did get to see her with the composer of the record's big hit (and her biggest hit), 'Me & Bobby McGee'.

"One day, when I walked into the studio, Janis was sitting on the lap of this really good-looking guy and she said, 'Glen, this is Kris Kristofferson. He's gonna be a big star someday.' I had never heard of him at that time, so I said, 'Glad to meet you, Kris. But you know, if you want to be in show business you might consider changing your last name...' She was already a superstar, we had closed sessions because everybody wanted to be around her, and so I was thinking, 'What does this guy want?' I had no idea they were an item and that he had written 'Bobby McGee'.

"Paul Rothchild, meanwhile, was like a dictator, and I was really pissed off at him. I remember him asking her to sing one of the songs and her screaming her lungs out, and at one point he said, 'Let's listen to the drums.' I said, 'Yeah, well, maybe we should tell Janis that we're gonna be working on something else so she doesn't have to blow her voice out,' and he said, 'No, no, let her sing! It's good for her voice!' I didn't think that was fair, but he was the boss, he was the producer, and so she was just left to keep belting while we turned our attention to other things. I wasn't really a big fan of Rothchild and the way he was treating people, and shortly after I left the project to work at Columbia's new studio in San Francisco.”

After Joplin was found dead on the floor of her room at the Landmark Motor Hotel, the official cause was determined to have been a heroin overdose, possibly exacerbated by the effects of alcohol, yet to this day Kolotkin has difficulty accepting that.

"One time in the studio, Janis was in the control room, the band was in the live area and one of the guys lit up a joint,” he recalls. "Well, Janis got on the talkback and said, 'Don't do that stuff! It isn't any good for you! If you want to get high, come in here. I've got something for you to get high on.' She was drinking Bénédictine and brandy, and at that time she was so against any kind of drugs that when I heard what had happened to her it was really hard for me to believe... If that's really what happened.”

The United States Of America

One of Glen Kolotkin's earliest mixing projects was the self‑titled — and only — album by the psychedelic rock band the United States Of America, whose use of strings, keyboards, audio processors such as the ring modulator and electronic instruments including primitive synths briefly established them as underground innovators, as did their then‑radical avoidance of the normally ubiquitous electric guitar.

Produced by David Rubinson, the album was recorded at Columbia's New York facility in December 1967 and released the following March to mixed reviews and poor sales. The group split up a short time later, yet its sole opus has since been reappraised by critics on both sides of the Atlantic as one of the most experimental and exciting works of the psychedelic era, and Kolotkin now recalls how "We were doing every kind of special effect at the time, even though in terms of equipment we really didn't have anything other than equalisers and echo units.

"Columbia built a special 16‑track room and we had 16 equalisers and 16 compressors, whereas the other rooms only had a couple of each because they weren't really geared up for that. This was a new room especially made for rock & roll, and I remember Ray Dolby coming down and trying to talk everybody into using his new system, which we did, while I also met Robert Moog there. I think CBS bought at least two of his huge synthesizers, because they were trying to keep up with things, but they still built their own consoles according to what we wanted them to do.

"For the United States Of America album, we were doing things like copying tracks and putting them backwards on the multitrack, as well as a lot of different tape effects, sometimes using separate machines with various tape delays, going at different speeds and mixed together. We had plenty of tape recorders, that's for sure! But outboard equipment was very sparse. The echo units were these huge EMTs, about eight feet long by five feet high, and they had a whole room of them; around 45 in the remix department alone, and you could patch them to any of the 10 remix rooms. It was very exciting to be working there, and so interesting to actually be creating stuff.”